James Butler Bonham faced his moment of truth in the pre-dawn of March 6, 1836.

He and a handful of Texians reportedly manned an elevated artillery position at the back of the church at the Mission

San Antonio de Valero—better known as the Alamo. Mexican soldiers were coming through the front door and charging up the dirt and wood ramp leading to the cannon. The exact details are lost to history, but many historians believe the defenders, probably among the last Texians killed in the battle, died at their post.

Today, some 2.5 million people visit the church each year, fascinated by one of only two Alamo structures still standing (the other is the Long Barrack). Inside the church, they may see a young man standing near the location where Bonham probably fell. He is not dressed in period clothing: he is wearing blue slacks, a white shirt, a red vest and an Alamo tie. But, in a strange way, he is emulating Bonham and his efforts.

“I guard the shrine,” he says. “I have to make sure nobody brings any food or drinks. That gentlemen take off their hats. No photography. And answer any questions anybody has.”

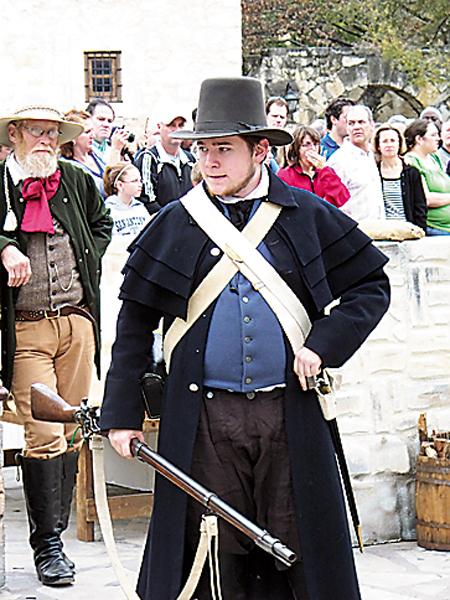

His role is not as glamorous as Bonham’s defense—and certainly not as dangerous. Yet it is a labor of love for Wade Dillon. On a few occasions each year, he does more than “guard the shrine.” He joins dozens of other Alamo aficionados, re-creating and portraying their heroes from the legendary battle. Wade becomes James Butler Bonham, giving flesh and blood to a man long gone into history and legend. In doing so, Wade gives onlookers a better perspective on the real-life defenders who met their maker 175 years ago.

That’s because Wade is a re-enactor. You know, those folks who dress up like famous (or lesser known) characters and act out battles, gunfights and other historic events. Countless thousands of people do it across the United States.

The stereotype goes that re-enactors are, well, a little strange. Yet let’s be clear about something; Wade is not some nut who cannot get a life and loses himself in a fantasy world in which he is the hero. He may or may not be a history geek. But he does have a firm grasp on who he is, versus the life and personality of his character James Bonham.

Bonham was about six feet tall, had black hair and just turned 29 at the time of the battle. Wade is 22, five feet and eight inches tall with brown hair.

Bonham had an upbringing of wealth and privilege. Wade’s family is in danger of losing their home in the economic downturn.

Bonham was fiery—he once caned an opposing lawyer during a court case; when the judge admonished him, Bonham threatened to tweak his nose (and spent 90 days in jail as a result). Wade is more subdued and thoughtful, an aspiring writer and accomplished artist.

But both left their homes in the southeast (Bonham from South Carolina, Wade from Florida) to seek adventure in Texas. And both found it at the Alamo.

Wade’s Way to San Antone

Wade cannot really remember a time when he was not fascinated by the place and event. “It began as a child when, after watching films or documentaries on the Alamo, I would act out the battle,” he says. “I’d play both Davy Crockett and William Travis, and my brother Joshua would play Jim Bowie. Together, we’d defend the Alamo while surrounded by our toy boxes.”

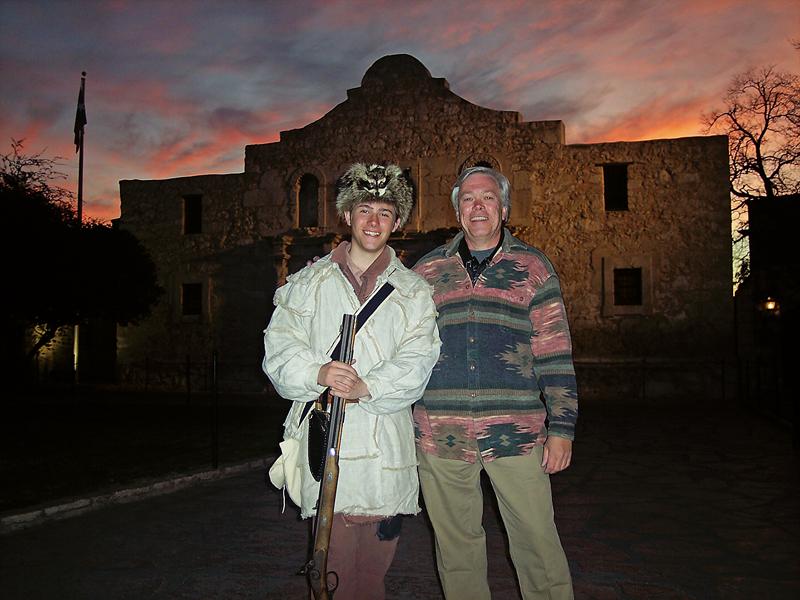

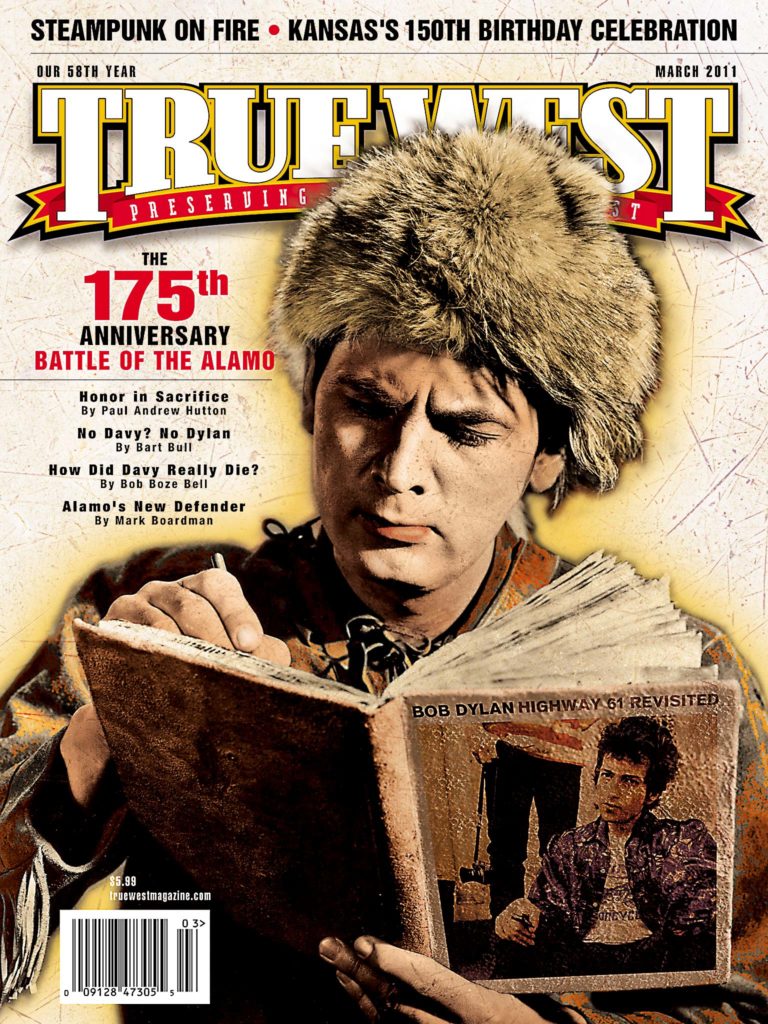

As a kid, he wore a coonskin cap a la Fess Parker, the “King of the Wild Frontier” Davy Crockett of the Disney TV shows.

In 1998, nine-year-old Wade and his family made a trip to San Antonio, specifically to see the shrine. “My father, my mother and my brother and I hopped on a taxi from our motel to the front of the Alamo,” he says. “I nearly jumped out of the door. It was bigger than life.”

The visit left a lasting impression—in part because it was the last Dillon family vacation. Wade’s mother died five months later. If anything, the loss only increased the youngster’s focus on the Alamo.

Allen Dillon supported his son’s interest, helping him buy period gear and providing encouragement and words of wisdom. Eight years ago, the pair built a copy of the Alamo church’s famous facade “hump” on the elder Dillon’s childhood home.

By age 15, Wade had set up a website about the Alamo (it’s now defunct and has been replaced with a Facebook page: Alamo Forever!). Using his website as a vehicle, the teenager interviewed several folks associated with the 2004 film The Alamo, including Director John Lee Hancock and star Billy Bob Thornton (who played David Crockett).

Wade got his high school diploma in 2007. His father’s graduation gift? A trip to San Antonio to participate in the Battle of the Alamo re-enactment, which is put together each year by the San Antonio Living History Association (SALHA).

“I wasn’t the most authentic looking, and I sported a coonskin cap and hunting frock coat,” Dillon says. “Thankfully, the gentleman portraying Crockett didn’t mind. Since then, we’ve become good friends.

“I took the sights and sounds in. Period music. Great people. And visitors wanted my photos left and right. I felt like a celebrity for a day. From that point on, I decided to improve my impression for future events.”

Over the next couple of years, Wade worked on that impression and attended re-enactments. He studied and researched the period, looking for information on clothing, weapons, language, culture and all things Alamo 1836 related. In a sense, Wade was self-educating himself in preparation for the future.

When he hit 21, Wade made his way West. The move took guts. He did not have a job or a place to live. He had contacts, but nowadays that will only get a person so far.

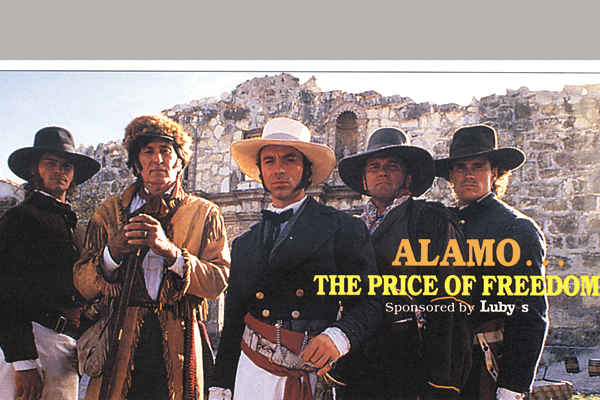

Wade eventually got a job at the IMAX theater next to the Alamo. The job was not exactly glamorous; he ushered and introduced the theater’s exclusive film, Alamo: The Price of Freedom while dressed as an Alamo defender.

Last October, he became a tour guide at the Alamo itself. Among other things, the job requires him to be patient with folks who have some very wrong ideas. “Many people think all the defenders died in the church,” he says. “Some think the church was moved from another location to downtown to attract tourists. And others think that the Alamo was blown up at the end of the battle, like John Wayne’s did in his movie.”

At times, Wade gets frustrated, trying to correct the myths and legends pushed forward by popular media. But he downplays that: “I am living the dream here in Alamo City!”

Paying for the Dream

A re-enactor’s dream is not that easy, and it sure ain’t cheap. If you’re Wade, you’re constantly reading new material on the battle and its participants. You talk to historians who are researching the Alamo. You’re always upgrading your period clothing and weaponry. In fact, Wade recently got a new hat, and a friend is making a frock coat for him. On his wish list: a Brown Bess musket and a short sword.

Authentic accoutrements are costly. Firearms can cost a couple hundred to a couple grand. Clothing is usually custom made; a museum-quality coat can sell for $2,000 or more. Wade upgrades as he has the money.

Committed re-enactors tend to bleed for accuracy. They want everything to be right. It’s a point of pride. But they also feel a certain amount of fear—of other re-enactors. They call them “stitch counters,” those who know the real from the bogus, down to the needlework in a shirt, and they are more than willing to point out mistakes. Wade says some visitors know their stuff too: “They’ll come up to you and ask, ‘Why are you wearing a Doc Holliday coat? What Tombstone website did you get that off of?’”

Upgrading to authentic clothes and gear is not a big fear for folks like Wade, younger re-enactors who can put in the time and effort to make things right. But they can’t control what others do. “A lot of older re-enactors don’t really look authentic because for the last 20 to 30 years, they haven’t wanted to change their gear or continue with the research,” he says. “And the research ought to be an ongoing thing.”

Portraying the Past

Each year, at the anniversary of the Alamo battle, the San Antonio Living History Association puts on the re-enactment. For those demanding absolute fidelity to the past, well, they’re going to be disappointed.

The main problem is the 1836 Alamo was much larger than the current structure, which is composed of just the church and the Long Barrack. Retail shops, the old post office, streets and other structures now cover the locations of the original walls. That limits the size of the re-enactment too. “SALHA sets off a boundary area in front of the church, where the street used to come through, probably about 20 yards from the church entrance,” Wade says. “It’s small. People don’t get the sense that they defended about four-and-a-half acres of compound. They were spread thin. In the re-enactments, we’re shoulder to shoulder.”

The re-enactors do have other opportunities to communicate the historic event to the public. “I have recently participated in ‘First Saturday’ events at the Alamo, which the Alamo personally puts together on the first Saturday of every month,” Wade says. “We do living history demonstrations, drills, weapon and medical equipment displays, camps, etc.”

Wade has also played a more personal role at the Alamo, one that utilizes another creative talent of his; he has portrayed a company field artist, which many military outfits had during the pre-photography days. Wade sketches impressions of the people and events in front of him, which often attracts an audience curious about what he’s doing.

No matter what part the re-enactor plays or the re-enactment, the experience is interactive. Audience members are encouraged to talk with the re-enactors, ask questions, make comments. Wade says most of his comrades are glad to share what they know, as they hope that they can educate folks about the battle, which makes it rewarding for everyone.

Whither Goest Wade?

But where does a life as a re-enactor lead? Re-enacting doesn’t pay anything. And a tour guide gig, even at the Alamo, is not highly compensated. The job seems okay for a young guy to take on, but it doesn’t seem to be a promising career.

Of course, when you’re 22, like Wade, you don’t worry too much about the future. He says maybe he’ll become a teacher, perhaps a history teacher, using his knowledge and abilities to bring lessons to life. Or perhaps the artwork will pan out. Or the writing. Or maybe he’ll work at the Alamo for 20 years, like some of his fellow guides.

But for now, Wade Dillon is living the dream. And he sees no reason why his dream has to end just yet—not while folks still remember the Alamo.

Photo Gallery

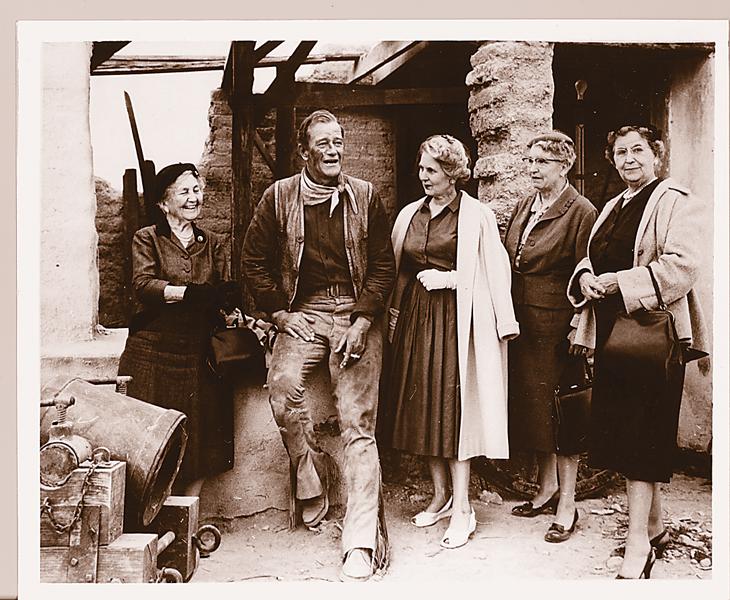

John Wayne, who starred in 1960’s The Alamo, with ladies from the Daughters of the Republic of Texas.

– Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton –

As of press date, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas had not confirmed what events will be held to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the battle—and that includes the annual re-enactment put on by the San Antonio Living History Association.

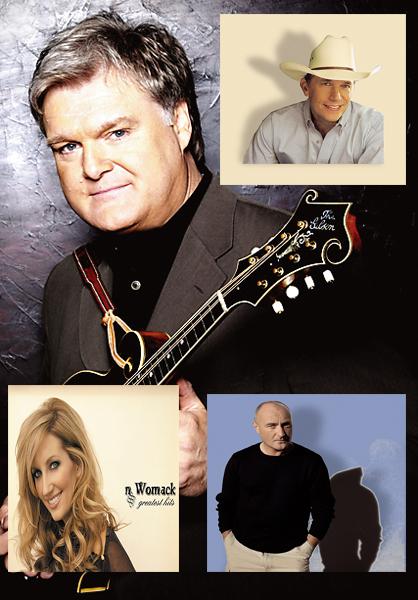

One celebration is set in stone—a concert of national and Texas patriotic music by the San Antonio Symphony. The sundown presentation on March 5, 2011, will be held directly in front of the church shrine. Additional performers include Country stars Ricky Skaggs, George Strait and Lee Ann Womack. Phil Collins—the Rock singer who has one of the top private collections of Alamo items—will read from letters written by William Barret Travis during the siege, and he’ll follow his up with some of his Rock hits.

The concert is free and presented by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas and the City of San Antonio.

True West’s Song Requests!

Ricky Skaggs & Lee Ann Womack: “San Antonio Rose,” a tribute to an old flame, which includes the lines: “It was there I found beside the Alamo/ Enchantment strange as the blue up above/A moonlit pass that only she would know/Still hears my broken song of love.” For a September 11, 2010, concert in Nashville, Womack opened her set with “San Antonio Rose;” it would be terrific to hear her sing the song with Skaggs, who included the Bob Wills song on his 1995 album Country Pride.

George Strait: “Remember the Alamo,” about a marriage proposal at the historic battle site, which includes the lines: “There by the mission you let your position be known/That you loved me so/Don’t forget where it started/Remember the Alamo.”

Phil Collins: “The Ballad of Davy Crockett.” Collins says his love for the Alamo all started with this 1955 Disney film starring Fess Parker as Davy Crockett, so why not sing the theme song most of us know and love