Death—that one great certainty of life—haunts us all.

It terrifies us—like children fearful of the dark—all the while calling to us, fascinating us, seducing us.

No writer ever captured this dreadful dichotomy more eloquently than William Shakespeare in Hamlet’s soliloquy. In turn John Ford used it as a metaphor for the American frontier in a compelling scene in his 1946 Western classic My Darling Clementine, when the brooding Doc Holliday recites, in part:

The undiscovered country, from whose bourn

No traveler returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than to fly to others we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all

But there are those who indeed make that bold decision—to go forth to that undiscovered country—to die a purposeful death for some greater cause than themselves. So bold an act captivates us. Perhaps that is why we so cherish the ideal of the last stand—of the grand gesture and glorious death.

Perhaps that is why, after 175 years, we still remember the Alamo.

This sentiment is not new. Similar battles have long fascinated humanity, and people from many nations pridefully embrace “last stand” tales from their history. While details may differ, the stories have a stunning similarity: the heroes are always vastly outnumbered by a culturally inferior enemy bent on the utter destruction of their civilization; the heroes resist with a fierce élan even though the struggle is hopeless; although doomed they purposefully die in order to buy time for their compatriots; their glorious death wins a spiritual victory that inspires their people; and their leader becomes a national hero, while the lost battle becomes a symbol of cultural pride.

Such indeed have been the grand tales of Saul atop Mt. Gilboa, of Leonidas holding the pass at Thermopylae, of Roland at Roncesvalles, of Lazar at the plains of Kossovo, of Custer on the Little Big Horn, and of Gordon’s doomed defense of Khartoum. The trinity of Alamo heroes—William Barrett Travis, Jim Bowie and, above all, Davy Crockett—rest comfortably amongst these martyred immortals.

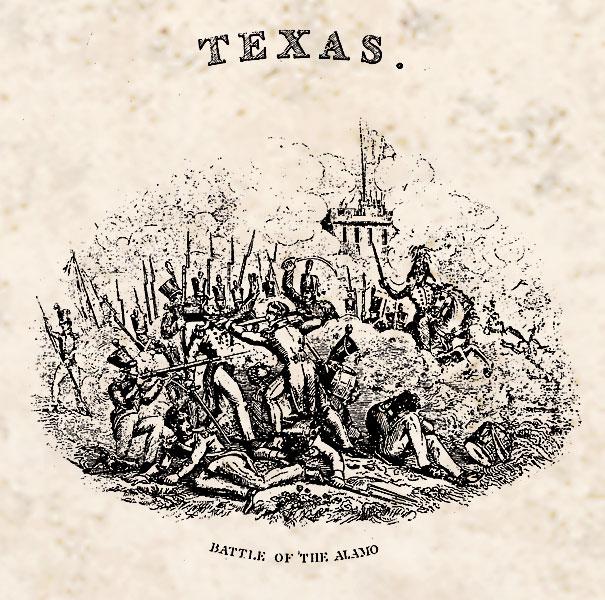

The Battle of the Alamo on March 6, 1836, while holding enormous cultural and symbolic power as one of America’s great legendary moments, was also of considerable practical importance as a historical event. The famed battle cry “Remember the Alamo” was no mere public relations stunt but rather an inflammatory and inspirational call to vengeance that led Sam Houston’s little army of Texians to victory over Mexican Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna’s forces at San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. Texas independence was won.

When, a decade later, Texas entered the Union, war with Mexico promptly followed. The Alamo was not forgotten by the American volunteers who stormed Chapultepec Castle in 1847, fulfilling America’s continental destiny and status as a rising world power. The fall of the Alamo had helped to set in motion a chain of historical events that forever altered the course of American, Mexican and world history.

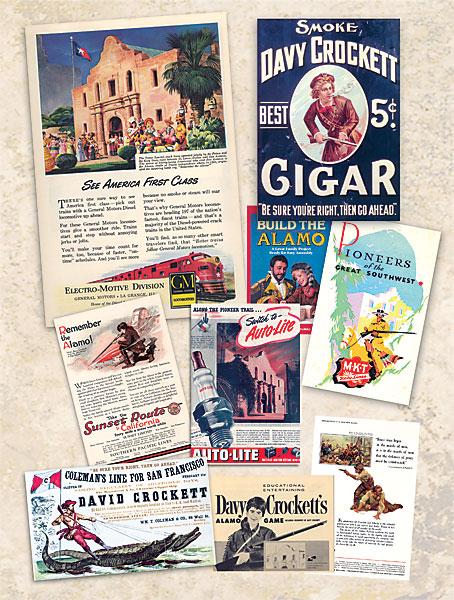

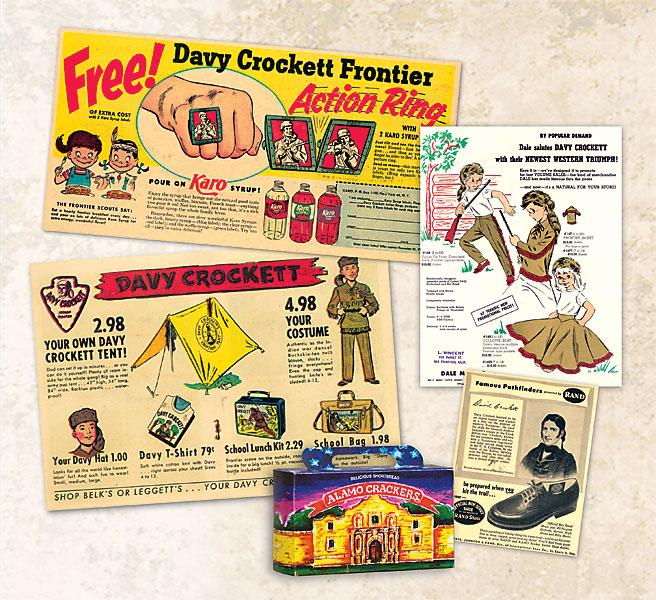

As with so much of our Western frontier heritage, since it is so clearly identified with the concept of American exceptionalism, the Alamo has increasingly become a flashpoint in the great cultural debate over our shared past as a people. The Alamo story has long been exploited by commercial, artistic, entertainment and political interests, but the last quarter century has seen a studied assault on its value as both history and symbol.

The battle is, of course, an obvious reminder of our troubled relationship with Mexico and has been invoked by both sides as the immigration debate has boiled over. Mexican Americans have rightly pointed out that the Alamo has often been used as an excuse for the repression of their political and social rights, and there has been considerable effort on the part of Hispanic intellectuals to deconstruct the so-called “Alamo myth.”

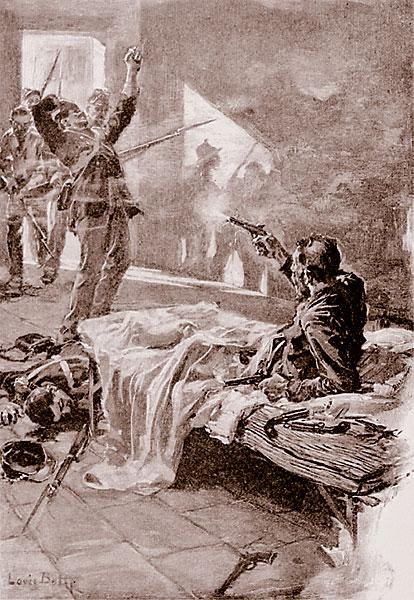

A new historiography has also emerged attacking the values represented in the defense of the Alamo and the integrity of its trinity of heroes. Slavery is now casually asserted in academic circles as a prime reason for the Texas Revolution, thus transforming the defense of the Alamo into a defense of slavery. A numbers game is played inflating the number of defenders and deflating the number of attackers (the number of Mexican casualties has long been a point of debate as well). The character of Travis has been assailed because of his failed marriage, of Bowie, over his shady land dealings and slave smuggling forays, and of Crockett, over his motivations for going to Texas and the manner of his death at the Alamo. (Did he die fighting heroically? Or was he captured and executed?) Recent writers have asserted that the defenders had a preplanned escape route and that many, if not most, of the garrison jumped the walls only to be slaughtered by Mexican dragoons as they fled. The heroic myth of defiance, and the grand gesture of the sacrificial death, are now dismissed as totally false.

As I reflect on the 175th anniversary of the fall of the Alamo, it seems to me that many of these writers and commentators have missed the power of this story. This is not to dismiss historical or interpretive debate, which is almost always of value, but rather to try and interpret the essence of the meaning of the Alamo at this moment in time.

We need look back no further than the tragic events of September 11, 2001, to find a modern historical parallel. Aboard the hijacked United Airlines Flight 93 passengers learned from cell phone calls of the planes crashing into the World Trade Center and decided to take action (it is now believed that the target of the Flight 93 hijackers was the U.S. Capitol or the White House). As they assaulted the cockpit the plane crashed near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, killing all on board.

A debate later ensued over if the passengers had breached the cockpit or not, which strikes me as not dissimilar to the debate over Crockett’s death at the Alamo. It ultimately is irrelevant, for the actions of the heroic passengers on Flight 93, whether they breached the cockpit or not, led to the crash and thus saved countless others at the intended target. They made the grand gesture, met the sacrificial death, went forth to Hamlet’s “undiscovered country.” So it was with the defenders of the Alamo, no matter the quality of their individual characters or motivations, no matter the details of their deaths, for they also made the grand gesture.

Our fascination with the sacrifice of the Alamo defenders may indeed be Shakespearean, but the essence of what it means to us today, on the 175th anniversary of the fall of the Alamo, is also as simple as the lines of Paul Francis Webster’s lyrics for the choral finale to John Wayne’s 1960 film The Alamo:

Let the fort that was a mission be an everlasting shrine

Once they fought to give us freedom,

That is all we need to know

Of the 13 days of glory at the siege of Alamo

Paul Andrew Hutton’s latest book, Western Heritage: A Selection of Wrangler Award-Winning Articles (University of Oklahoma Press), will be released in April 2011.

Photo Gallery

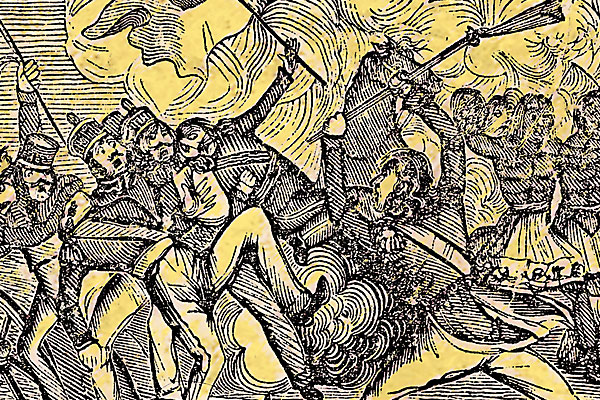

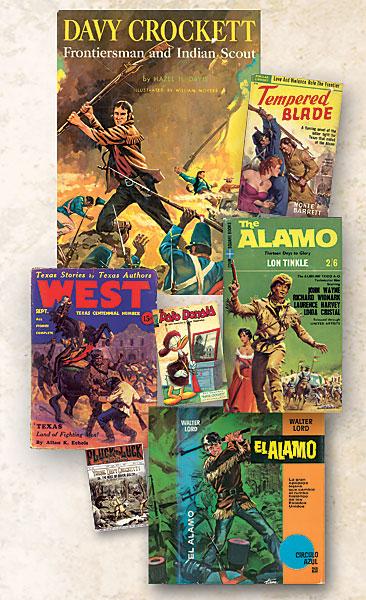

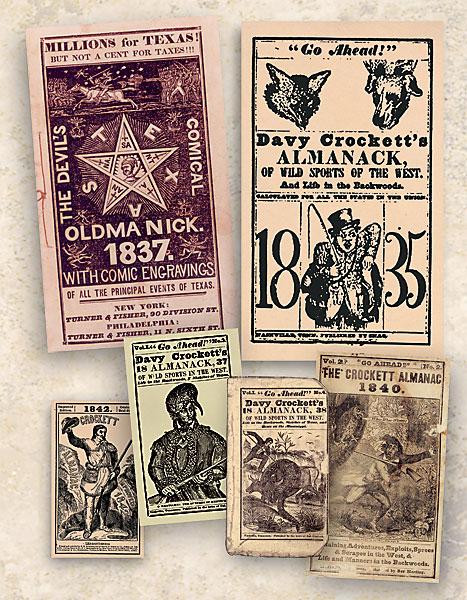

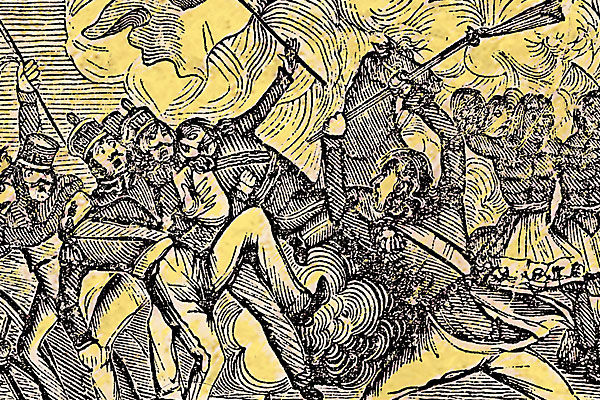

An early Alamo battle illustration from Ben Hardin’s Crockett Almanac for 1842. At least 45 Crockett Almanacs were published between 1835 and 1856 by various companies. They were the forerunners of the post-Civil War dime novel.

– All images courtesy Paul Hutton unless otherwise noted –

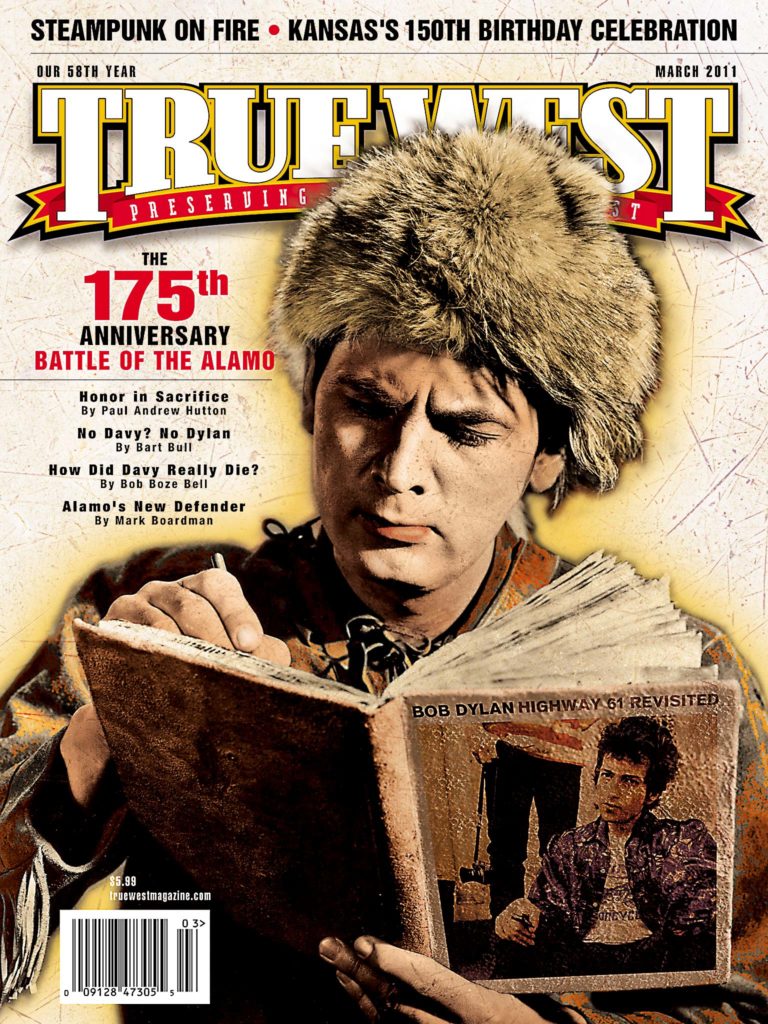

Famed Shakespearean actor James Hackett played the Crockett-inspired Col. Nimrod Wildfire in The Lion of the West, which premiered in New York City in 1831. The real Congressman Crockett attended a Washington, D.C. performance in 1833.