The Courageous Life and Death of Oliver Loving

In 1867, beneath a bluff a few miles from Carlsbad, New Mexico, two Texas cattlemen—one of them a trail-hardened 52-year-old, the other a 23-year-old roughneck—were fighting for their lives, surrounded by a marauding party of Comanches. If recorded at all, such an event would have been no more than a blip on the historical calendar of the American West, but this one—and its aftermath—turned out to be one of the most amazing examples of courage, loyalty and sheer grit in all the annals of the frontier.

Courtesy Frederick Nolan

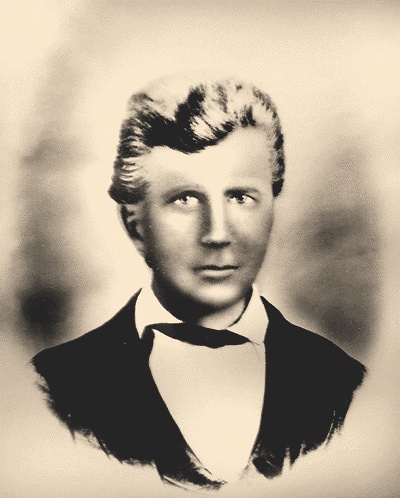

Kentucky-born Oliver Loving was a remarkable cattleman-entrepreneur who, in 1858, partnered with John Durkee in taking a herd from Palo Pinto County in Texas to Chicago, Illinois, the very first such drive on the historical record. In 1859, he blazed another trail to Denver via Pueblo, Colorado, and throughout the Civil War, he supplied the Confederacy with beef. In 1866, he teamed up with a 30-year-old cattleman named Charles Goodnight, well over 20 years his junior.

They put together a herd of 2,000 and blazed a new trail up the Pecos River into New Mexico and on to Denver, Colorado. The following year, they started another herd west over the same route, striking the Pecos during the latter part of June. About 100 miles upriver, Loving traveled ahead of the herd on horseback in order to bid on the contracts, which were to be let in July.

Because Loving was impatient, even reckless, Goodnight not only insisted he be accompanied by one of Goodnight’s top men, Arkansas-born herder Bill Wilson, who had already lost an arm sometime during his 20-odd years, but also made Loving promise to ride only by night. After only two nights, however, Loving—who detested night riding—talked Wilson into changing tactics so they could proceed by daylight.

Loving probably didn’t have to work too hard: by all accounts—including this one—Wilson was a man ready to ride any river, with many stories spun about him. He was said (unreliably) to hold off a posse after one of his brothers, George, shot a sheriff in Palo Pinto County. The matter of his lost arm is also a moveable feast: it may have been bitten off by a mean horse before Wilson was five years old, or it may have been congenital. Another story claims a hay baler ripped it off, which would be historically inconsistent, since the injury happened before the 1860s.

Crossing the plain in broad daylight, the two riders, visible for miles, were spotted by a Comanche raiding party that came thundering after them. The cowmen made a four-mile run for the Pecos, spurring their horses over an incline and down to a sand dune at the foot of a bluff, where it formed a shallow cave open to view only from across the river. As the Comanches surrounded them, Loving and Wilson readied themselves for a fight to the death.

Courtesy Altermann’s Auction

Fighting For Their Lives

Wilson was armed with a revolving six-shot rifle and saddle holsters as well as his own cap-and-ball six-shooter, while Loving had pistols and a Henry rifle. The Comanches—Wilson estimated that they numbered several hundred—swarmed down the bluffs around them, but the

first one who fired at the cowboys from across the river got shot by Loving, after which no others tried to open the ball.

Late in the evening, the drovers heard someone call from the bluff in Spanish. Realizing it could be a trap, but with the situation bordering on hopeless, Wilson took a chance and stepped up on the dune to parley, with Loving behind him, Henry rifle in hand, his holsters across his arm. As Wilson stepped into view, Indians hidden in a clump of carrizo, or cane, opened fire, with one of their bullets smashing through Loving’s wrist and ploughing into his side. Wilson hastily fell back into the ditch, giving his attention to Loving. After staunching the bleeding, they readied themselves for a siege.

“The Comanches shot their arrows high into the air to make them fall at a sharp angle into the ditch, while Wilson and Loving hugged close to the low but perpendicular wall of the washout, and the arrows either stuck in the sand above them or passed over their backs into the other bank,” Goodnight told J. Evetts Haley in the 1920s. He would share the cowman’s life story in his 1936 book.

Courtesy Frederick Nolan

Next, Goodnight recalled, the Comanches tried bombarding their quarry with gravel, but that didn’t work either.

The evening wore into dusk; weak from loss of blood, Loving was racked with pain and fever. Wilson managed to get to the river and brought back a bootful of water for the suffering man, but Loving’s condition worsened, and he implored Wilson to escape, if possible, and carry the story of his fate downriver to Goodnight and to his family. “I’ll stand the Comanches off the best I can,” he told Wilson, “but rather than be taken and tortured to death, I will shoot myself and fall into the river. If the Indians leave me and I find strength enough to travel, I’ll head downstream a couple of miles and hide.”

Wilson agreed to make the attempt. They calculated carefully; if he could hold out for a day and a half, he would have a good chance of meeting the advancing Goodnight.

“He spread their five six-shooters and Goodnight’s rifle by Loving’s sound arm, but took the Henry and its metallic cartridges, which would be unaffected by water, for to escape by the river was his only chance,” Goodnight said. “When the moon went down, he told Loving goodbye, moved to the mouth of the gully, and divesting himself of his clothing, hid his clothes in one place, and his knife, which dropped from his pocket, in another, all beneath the water. He pulled off everything but his hat, drawers and undershirt, which he hoped would protect him from the sun, and slipped into the treacherous stream.”

A Swim For Survival

The river was quite sandy and difficult to swim in, Wilson recalled, “so I had to pull off all of my clothes except my hat, shirt and breeches.”

Courtesy Haley History Center in Midland, Texas

He nearly drowned, trying to hold on to the rifle with his one hand, so he “leaned it up against the bank of the river, under the water, where the Comanches would not find it,” Wilson said. “Then I went down the river about a hundred yards, and saw an Indian sitting on his horse out in the river, with the water almost over the horse’s back. He was sitting there splashing the water with his foot, just playing. I got under some smart weeds and drifted by until I got far enough below the Indian where I could get out. Then I made a three days’ march barefooted. Everything in that country had stickers in it. On my way I picked up the small end of a tepee pole which I used for a walking stick.”

On the last night of his slow and painful journey, he was followed by wolves all night. “I would give out, just like a horse, and lay down in the road and drop off to sleep and when I would awaken the wolves would he all around me, snapping and snarling. I would take up that stick, knock the wolves away, get started again and the wolves would follow behind. I kept that up until daylight, when the wolves quit me,” Wilson recalled. “About 12 o’clock on that last day, I crossed a little mountain and knew the boys ought to be right in there somewhere with the cattle. I found a little place, a sort of cave, that afforded protection from the sun, and I could go no further [sic]. After a short time the boys came along with the cattle and found me.”

During their earlier drive to Denver, Loving and Goodnight had discovered a valley about two miles long and a mile wide close to the New Mexico line, near the upper end of which were some gravel hills; in one of them, a cave extended back 10 or 15 feet, which they marked as a splendid hiding place for Comanches planning a surprise attack.

“[I] was…watching carefully for Indians,” Goodnight remembered, “suspecting they might be behind the hill, [when] I saw a man come out of the cave and go back into it.”

True West Archives

Goodnight gave orders for the herd to be held and for the men to be ready for a fight. When Wilson came out of the cave, a quarter of a mile away, and gave the old frontier signal, ‘Come here,’ Goodnight said he “knew positively that it was Wilson, and…I immediately put the horse down to full speed and went to him. For a few moments he seemed unable to talk, probably overwhelmed with emotion, knowing his life was saved at last.”

With what was left of his underwear, saturated with red sediment from the river, Wilson was the “most terrible object I ever saw,” Goodnight said. “His eyes were wild and bloodshot, his feet were swollen beyond all reason, and every step he took left blood in the track. I inquired about Loving, but he could scarcely make a reply, and what he did mutter was entirely unintelligible. I put him on my horse and got him to the herd as soon as possible…I tore up a blanket, wet it, wrapped his feet to remove the fever and then made him a light meal of gruel, which I gave him at intervals for about an hour. By then he was perfectly himself. I asked him for particulars and he told me in detail of the trip and the attack by the Indians.

“When Wilson finished his story, I decided to start immediately.… We rode the rest of the evening and all that night. It not only rained, but it rained torrents, and was so dark at times we were forced to halt. When I reached the place where Wilson told me he had left the trail, I recognized it easily from his description, although the plains were unmarked, or would have appeared so to the untrained. Besides his description, the place was distinguished by the fact that a bunch of Comanches had again come out of the mountains and passed over the same trail they had taken when chasing the two men. Their tracks seemed as fresh as ours, and we supposed they were under the bluffs still trying to get Mr. Loving…[but] when we got to the top of the bluff, there was not an Indian in sight.

Courtesy Charles Goodnight Historical Center in Claude, Texas

“In a moment, I found where Mr. Loving had been in the ditch, which was now half filled with stones, and its banks perforated with probably a hundred arrow shafts, though the Indians had gathered the arrow[head]s before leaving. I knew they had not got him, as there was ample evidence that they had been hunting for him everywhere. We searched down the river…but…no tracks could be found. I believed he had carried out his threat; that he had shot himself and floated down the river, the torrent obliterating all traces. After dark the party sadly made its way back to the herd and again took the trail.”

But Loving was not dead.

Loving’s Courageous Crossing

After Wilson left, the Comanches had continued to shower Loving’s position with rocks, and they tunneled through the dune to within a few feet of where he lay, but lacked the courage to get closer. Racked with hunger and the fever of his wounds, he somehow managed to keep his attackers at bay, but few men could endure a shot-shattered wrist and three foodless days and sleepless nights without collapse. In spite of his age, however, Loving was blessed with an iron constitution. When no help showed up, he followed Wilson’s lead. On the third night, he crawled into the water and started upstream, instead of downstream, hoping to reach the trail crossing [present-day Carlsbad] about six miles above, where some passerby might help him.

“At last he gained the crossing and lay down in the shade…about four feet above the water,” Goodnight told Haley. “He attempted to shoot some birds that came into the trees, but the river had soaked his powder and caps, and the guns were useless. He tried to eat his buckskin gloves, but could not kindle a fire to parch them to a crisp, and again settled back to wait. For two days and nights he stayed there, too weak to move, but satisfying his thirst by tying his handkerchief to a stick and dipping it in the river below. On the third day his superb endurance broke and he sank into a stupor.

“Three Mexicans and a German boy, in a wagon drawn by three yoke of oxen, passing through on their way to Texas, stopped at the crossing to prepare their dinner. The boy…found Loving, apparently asleep.… He was taken to the wagon, where the Mexicans prepared him some atole, similar to our corn meal mush…after which he offered them $250 to take him to Sumner, about 150 miles away.”

Meanwhile, Goodnight’s herd kept moving north. “About two weeks after this,” Wilson said, “we met a party coming from Fort Sumner, and they told us Loving was at Fort Sumner. The bullet which had penetrated his side did not prove fatal, and the next night after I had left him, he got into the river and drifted by the Indians as I had done, crawled out and lay in the weeds all the next day. The following night he made his way to the road where it struck the river, hoping to find somebody traveling that way. He remained there for five days, being without anything to eat for seven days. Finally some Mexicans came along and he hired them to take him to Fort Sumner.”

Some 30 miles from Fort Sumner, a courier brought Goodnight the news that although Loving was alive, gangrene had set in and his arm needed to be amputated. “Loving did not want the operation performed unless I was there,” Goodnight said, “as he feared he might not survive it…. The old doctor was in Santa Fe…and the young doctor put me off from day to day with various excuses…. Fortunately I found him at the hospital alone, and told him briefly and in no uncertain words that I presumed he was putting me off because we were rebels, and that he must now operate or make wounds on me.”

The doctor performed the amputation, and Loving seemed to be doing well. Just to be on the safe side, Goodnight paid a man (reportedly Winfield Scott Moore) $500 to ride to Las Vegas and bring back Dr. John H. Shout; they arrived two days later only to find out that Loving had suffered a relapse. “In spite of neglect, starvation and punishment he lived for 22 days, perfectly rational to the last, [when] his mind turned back to Texas,” Goodnight recalled, “and at last he said, ‘I regret to have to be laid away in a foreign country.’ I assured him that he need have no fears, that I would see his remains were laid in the cemetery at home [in Weatherford, Texas]. He felt that this would be impossible, but I told him it would be done.”

Loving died on September 25, 1867, and his body was temporarily buried in a simple wooden casket at Fort Sumner. Four months later, Goodnight returned.

Riding Shotgun

Over a Tin Casket

Transporting the remains of his friend back to Texas would be a daunting task, but the cattleman was determined to keep his promise. Gathering scattered oil cans from about the fort, his cowboys beat them out, soldered them together and made an immense tin casket. Inside this, they placed the rough, wooden one, several inches of powdered charcoal packed around it, sealed the tin lid and crated the whole in lumber. They lifted a wagon bed from its bolsters and carefully loaded the sarcophagus on to it. On February 8, 1868, with six big mules strung out in harness, the rough-hewn cowmen from Texas rode ahead and behind the strangest and most affecting funeral cavalcade in the history of the cow country, bringing Oliver Loving home. “The Pecos—the graveyard of the cowman’s hopes,” Goodnight humanized the bleak terrain.

“Down the relentless Pecos and across the implacable Plains, the [388-mile] journey was singularly peaceful,” Goodnight told Haley. “Through miles of grazing buffaloes, they approached the Cross Timbers, reached the settlements and at last delivered the body to the Masonic Lodge at Weatherford, Texas, where it was buried [in Greenwood Cemetery] with fraternal honors.”

Frederick W. Nolan is one of the foremost authorities on Billy the Kid and the general history of the American West. For more on Charles Goodnight, he recommends reading J. Marvin Hunter’s The Trail Drivers of Texas (the first book to feature Goodnight and Wilson’s stories) and J. Evetts Haley’s biography, Charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman.