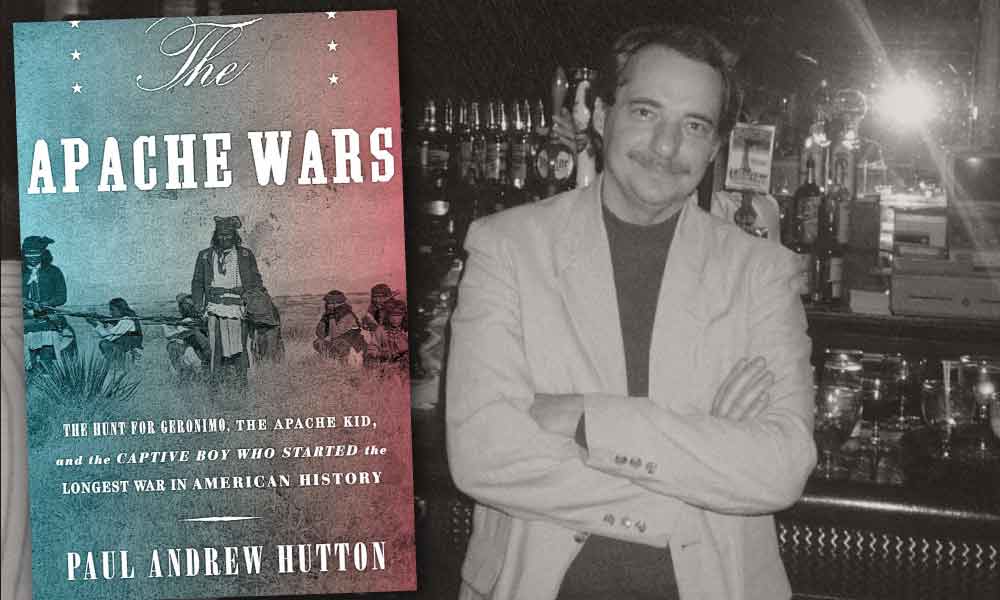

University of New Mexico Distinguished Professor Paul Andrew Hutton has balanced the academic with the popular for his entire career. He loves a good story, and he, much like Francis Parkman and Bernard DeVoto before him, has aimed to write epics that spread the romantic story of the American West.

His past magazine articles, books, television documentaries and even a film script on Davy Crockett, cowritten with David Zucker, have all informed his latest book, The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History, published by Crown.

The historical consultant for True West Magazine, Hutton talks about the year’s most anticipated Old West history book with longtime friend and Mickey Free collaborator Bob Boze Bell.

Executive Editor Bob Boze Bell: Why has Mickey Free been ignored?

Paul Hutton: Mickey Free is one of those fascinating characters who slipped through the cracks of the historical record. Part of the problem is with the man himself—for he was a coyote, a trickster and a shape-shifter. Mickey was impossible to tie down for he had so many personas—kidnapped child, slave, Apache warrior, U.S. Army scout. Was he a traitor or a hero? Was he a Mexican, a white man or an Apache—or was he all three?

There was a potboiler biography about him back in the 1960s that is unreliable, but some excellent work was later done by Victoria Smith and Allan Radbourne. You and I labored over a graphic novel/screenplay a few years back, but we could never capture the genie in the bottle. We may yet get him.

After being kidnapped in 1860, Mickey Free never went back to his original family. Why?

By the time Mickey met his brother Santiago during the Geronimo campaign, Mickey’s parents were both dead. He had no interest in reconnecting with his past or his family for he had moved on. He was not Felix Ward anymore. He was Mickey Free. As an orphan myself, this logic made perfect sense to me. He was also a “motherless child,” and it drew me to him as a kindred spirit.

Is the so-called Bascom Affair in 1861 correct, that Bascom blundered?

The traditional interpretation of the Bascom Affair is absolutely correct. Lieutenant George Bascom was an inexperienced, arrogant fool who bungled his way into an intolerable situation and could not figure a way out. The incident reminds me of the Grattan slaughter at Fort Laramie a few years before. Both incidents were avoidable, and both had major repercussions. If a more experienced officer, like Capt. Richard Ewell, had been at Apache Pass, there would have been an entirely different outcome. Bascom then lied about the entire incident in his official report.

I learned long ago to take all “official reports” from the military in the West with a large dose of salt. But Bascom did die a hero at the Battle of Valverde and deserves some honor for that.

In the popular imagination, Gen. George Crook is the good guy and Gen. Nelson Miles is a bit of a pompous ass. Is that true?

Crook was fortunate in his lifetime to have a superb press agent in John Bourke (who he later betrayed) and later to have Dan Thrapp, Robert Utley, Paul Magid and other fine historians on his side. I found Crook replete with contradictions. He was undeniably brilliant, especially when it came to unconventional warfare, but he was also stunningly arrogant. His conviction that he, and he alone, knew how best to deal with the Apaches led to disaster for both him and the Indians.

Miles, on the other hand, was remarkably flexible. He despised Crook as a fraud, which was not true, but in many ways, Miles proved the more able soldier both on the Northern Plains and in the Southwest. He was a man who got things done.

The same also applies to the controversy over who should get credit for Geronimo’s surrender—Charles Gatewood or Henry Lawton? Gatewood is usually identified as a Crook man who Miles only reluctantly turned to. But Crook had earlier abandoned Gatewood, and Miles had the wisdom to bring him back into the campaign. While Gatewood deserves enormous credit for Geronimo’s surrender, he never could have accomplished the job without the relentless campaign led by Lawton.

How did Geronimo go from being perceived as an evil terrorist to a freedom fighter?

This is a subject I wrote about in a True West article [August 2011]. My feelings on Geronimo are that he was a self-centered narcissist just like Gen. George Custer. That’s why I admire him. He was always only about Geronimo, never about the people. Was he bold, brave, charismatic and intelligent? Of course he was. Was he a patriot chief devoted to his people? Of course not.

That American popular culture has turned him into a patriot chief and freedom fighter is a pretty good joke. Geronimo, who brilliantly remade himself into a national celebrity after his capture, would have appreciated the humor. He is probably still laughing at how he won over the hated “White Eyes.” Custer has been diminished as an American hero, yet Geronimo has risen in status. Times change, and so does our view of the past.

How mobile were Apache warriors?

Landscape is vital to an understanding of the Apache Wars. The Apaches knew the land and used it to their advantage. They knew the water holes, the caves, the perfect ambush canyons and the mountain passes. The land was their ally. They always outran pursuing troops—be they Spanish, Mexican or American.

The Apaches were not horse Indians, like the tribes on the Great Plains, for they were a mountain people. Cochise’s band actually used leather covers for the sore hooves of their horses. This allowed observant scouts to immediately identify the band by their tracks. Horses were equal parts food and transportation to the Apaches. Horses did allow them to raid deeper into Mexico, but more often than not, they traveled on foot.

What about Apaches and dogs?

While some Plains tribes ate dogs, the Apaches domesticated dogs and treated them as pets and hunting partners. When the Americans came, the Apaches had to abandon their dogs to avoid detection by the Army patrols. Later, on the reservation, they reunited with their beloved pets. One of the most heart-wrenching stories of my book deals with the fate of the Fort Apache Reservation dogs when the Apaches were removed to Florida. I write long hand on yellow-sheet tablets, and I literally shed tears all over those pages when composing that chapter

Of all the Apache leaders, which include Cochise, Geronimo, Juh and Mangas Coloradas, who was the greatest?

Mangas Coloradas was the greatest of the Apache chiefs during the American period. He built a mighty alliance among the incredibly independent Apache bands and wielded more influence and power than any leader before or after him. His cruel betrayal and murder by the Americans infuriated all the Apaches. Geronimo proclaimed it the “greatest of wrongs.” The decapitation of Mangas led the Apaches to be even more brutal and to engage in more mutilation.

I was also deeply impressed by Cochise, my boyhood hero from the Blood Brother book and Broken Arrow film, and Victorio, the great Warm Springs chief. They were true patriot chiefs.

Lozen is dismissed by your mentor Robert Utley as being a made-up fantasy, yet you document her exploits. Why?

Several historians who I admire, most notably Ed Sweeney and Robert Utley, dismiss the story of Lozen as a fantasy. I found the tale of this great woman warrior and shaman to be incredibly compelling. Lozen, the sister of Victorio, was real, and her deeds are supported by Apache oral tradition. This comes down to us not only from Eve Ball, but also from multiple Apache sources. It is unfortunate that the “white historical record” does not recognize her. What an incredible character she was.

How is the Apache War the longest war the U.S.

has ever fought?

After the kidnapping of young Felix Ward—Mickey Free—the United States government was continually involved in a quarter century of warfare with the Apaches for possession of the American Southwest. Campaigns took place before 1861, against the Jicarillas and Mescaleros in New Mexico, and Col. Benjamin Bonneville’s 1857 Gila Expedition in Arizona, but Ward’s kidnapping was the spark that set the Apache Wars in motion. That war shaped the history of the American Southwest and northern Mexico.

Paul Andrew Hutton is the author of The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History, published in May 2016 by Crown. He has published 10 books and teaches history at the University of New Mexico.