The Indians’ ammunition grew on trees.

An arrow, the deadly projectile propelled from a bow, could arguably be called the Indians’ “bullet.” However, unlike the short lead round ball or conical slug fired by a gun, the arrow is a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty, sharpened or blunt arrowhead attached to the front end. On the rear are multiple fin-shaped stabilizers called fletchings, mounted along the sides, and a slot, known as the nock, at the back end for attaching the bowstring.

While the firearm’s bullets are only a few hundred years old, arrows predate recorded history by an estimated 64,000 years. Although historians debate just when this primitive weapon made its first appearance in North America, it’s generally believed to have started spreading from Alaska downward through North America sometime around 2000 BC. Since that time, the bow and arrow reigned as the primary arm the indigenous peoples of our continent relied on for both sustenance and warfare.

From the first encounter with Europeans up through the mid-19th century and the introduction of repeating firearms, the Indian bow and arrows were often superior to the slow-loading, single- or two-shot muzzle-loading guns employed by the white man. On the frontier, lead, gun powder, percussion caps or metallic cartridges could often be difficult to obtain, while the bow’s arrows literally grew on trees, and were easy to produce in quantity. The bow with its arrows offered rapid-fire, reliability, and in capable hands, close-range accuracy equal to that of the early firearms.

As Josiah Gregg, a veteran of many months living in the Southwest, recalled of Native American weaponry in the 1830s and 1840s, “The arms of the wild Indians are chiefly the bow and arrows, with the use of which they become remarkably expert…While the musketeer will load and fire once, the bowman will discharge a dozen arrows, and that, at distances under fifty yards, with an accuracy nearly almost equal to the rifle.”

As further testimony to the Indian archer’s speed and accuracy, an Army surgeon serving in the Southwest in 1862 noted that “an expert bowman can easily discharge six arrows per minute, and a man wounded with one is almost sure to receive several arrows…We have not seen more than one or two men wounded by a single arrow only.”

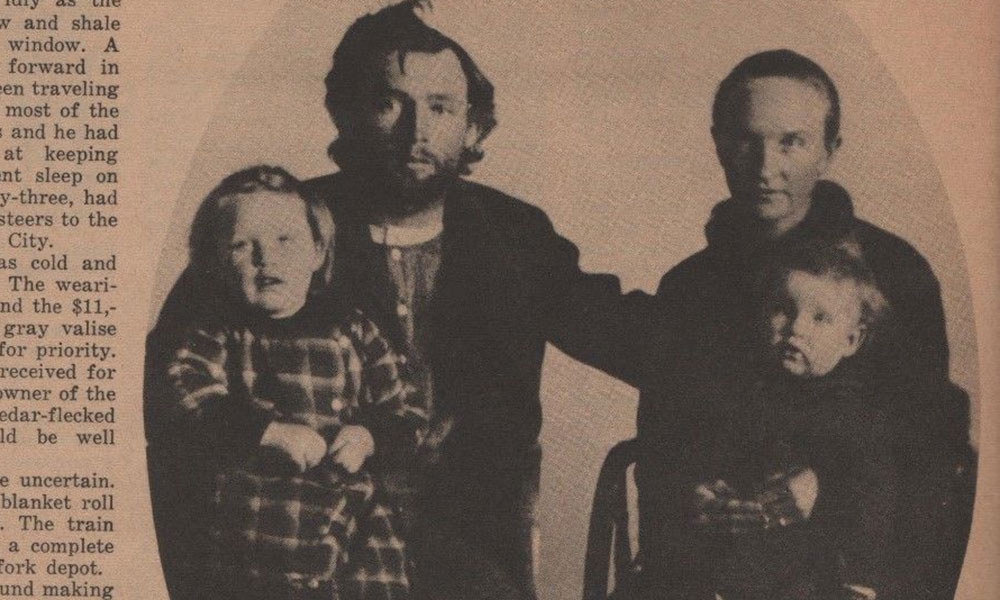

Phil Spangenberger Collection

To replenish his arsenal of arrows, an Indian could produce shafts from almost any type of local wood. Once a shaft was hand-straightened by heating over a fire, feathers of native birds were used for fletching. The feathers were tied to the shaft with animal sinew (and possibly glued with a sticky substance made from animal products). Arrowheads or points, could run from blunt-edged affairs—for stunning small game animals without harming the valuable meat, to simple sharp-pointed shafts. For a more deadly effect, hand-knapped flint stone or iron points, also attached by wrapped animal sinew, would be used. Iron arrowheads could be crafted from wagon wheel “tires,” barrel hoops or commercially produced heads acquired in trade with white settlers.

Courtesy Manifor Collection

Although there was no standardized length, arrows of the Plains Indians reportedly averaged around 22 to 24 inches in length, Southwestern tribes tended to run about 26 to 28 inches long, although there were some running as much as 30 inches or longer. Extra arrows were stored in soft quivers, usually made from elk, deer, buffalo or puma hides, and were either left plain, or in many cases decorated with trinkets and extra trappings like (flint and iron) strike-a-lights, extra sinew, spare metal arrow points and other useful items carried in small bags called fire bags.

As testament to the combat effectiveness, along with the high respect, of the Indian’s primitive bow and arrows, one frontiersman wrote, “It was to us a much more terrific weapon of war than a musket.”

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.