– Illustration by Bob Boze Bell –

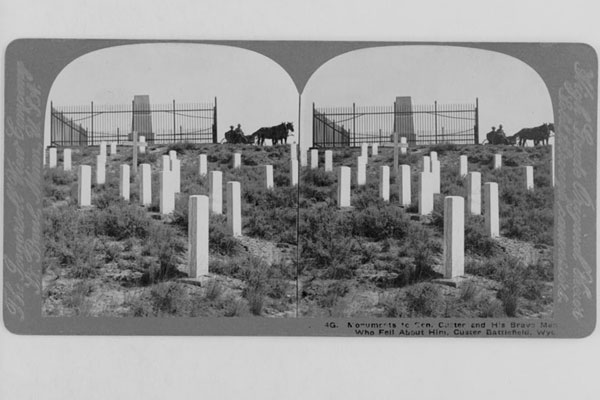

On June 25, 1876, the 7th US Cavalry crossed the Wolf Mountains and moved into the valley of the Little Bighorn. Custer was confident of his ability to handle whatever he ran up against, convinced that the Indians would follow their usual practice of scattering before a show of force and completely unaware that he was descending upon one of the largest concentrations of hostile American Indian tribes ever assembled on the Plains. Perhaps as many as 6,000 to 7,000 Sioux and Northern Cheyenne, with as many as 2,000 warriors under such capable leaders as Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, Gall, Crow King, Lame Deer, Hump and Two Moon, confronted Custer in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The foot soldiers were armed with updated Springfield Model 1873 rifles, and mounted troopers carried carbines. Both were provided ample ammunition.

Around noon on this Sunday in June, Custer dispatched Capt. Frederick W. Benteen leading three companies to scout to the left of the command. This was not an unusual move for a force still attempting to fix the location of an elusive enemy and expecting him to slip away on contact. It is also possible that Custer, knowing the value of the principle of surprise, hoped to catch his foe unawares. At about 12:30 p.m., still two miles short of the river when the upper end of a village came into view, Custer advanced three more companies under Reno with instructions to cross the river and charge the American Indian camp. With five companies, Custer moved off to the right, still screened by a fold of ground preventing him from observing the extent of his opposition. Perhaps his thought was to hit the Indians from the flank—letting Reno hold the enemy by the nose while Custer kicked him in the seat of the pants. As Custer progressed, he rushed Sgt. Daniel Kanipe to the rear to hurry the pack train and its reinforced one-company escort, urging it forward into what soon erupted into a firefight. Shortly afterward he dispatched Trumpeter John Martin (aka the Italian-born Giovanni Martino) with a last message to Benteen that a “big village” lay ahead and to “be quick—bring packs,” which would have contained important extra ammunition, if the firefight had lasted any length of time, which it did not.

– Courtesy Glen Swanson Collection –

Indeed, the main phase of the Battle of the Little Bighorn ended in something like two hours or less. Reno, charging down the river with three companies and some Arikara scouts, ran into hordes of American Indians, not retreating, but advancing, perhaps mindful of their creditable performance against Crook the week before and certainly motivated by a desire to protect their women and children and cover a withdrawal of the villages. Greatly outnumbered, suffering heavy casualties, and in danger of being overrun, Reno withdrew to the bluffs across the river and dug in.

In the meantime, Custer and the five companies with him, about 230 strong, moved briskly along the bluffs above the river until, some four miles away, they were beyond supporting distance and out of sight of the rest of the command. They were brought to bay and overwhelmed by an Indian force that heavily outnumbered them. Many troopers were struck down before they could mount a defense.

In the wake of the ignominious debacle, a shocked nation, including many in the US Army, questioned the outcome. How could the “Boy General” and his hard-riding, elite 7th Cavalry be vanquished?

Among the answers was a contention that firearms had played a major role in the Little Bighorn tragedy. Writing just two years after the battle from a fort in Montana that bore Custer’s name, one officer repeated a theory that began to circulate within some elements of the Army. In an unsigned letter published in The Army and Navy Journal on November 30, 1878, he wrote: “When our men are engaged in actual combat with a wily foe, it would be nothing more than fair that our government should supply our soldiers with the best rifles and carbines in the civilized world. If we are several years behind in regards to best rifles, it is time for us to wake up and see if something cannot be done to place us on equal footing, not with civilized nations, but with red men themselves.”

What this critic and others failed to admit was—as 1st Lt. Holmes Offley Paulding, a surgeon who attended to the survivors of the slaughter, noted—“cavalrymen…as a general thing are about as well fitted to travel through hostile country as puling [sic] infants.” The fact was that during the second day of the Little Bighorn fight, officers with Major Reno’s surrounded force had to give permission to their men to fire, in order to conserve ammunition as they realized most of the troopers were poor shots. Edward Godfrey, a lieutenant with the 7th Cavalry, later recalled seeing one of the men pull “the trigger. There was a perceptible dropping of the muzzle, and a flinch, but no report. He had forgotten to cock his piece.”

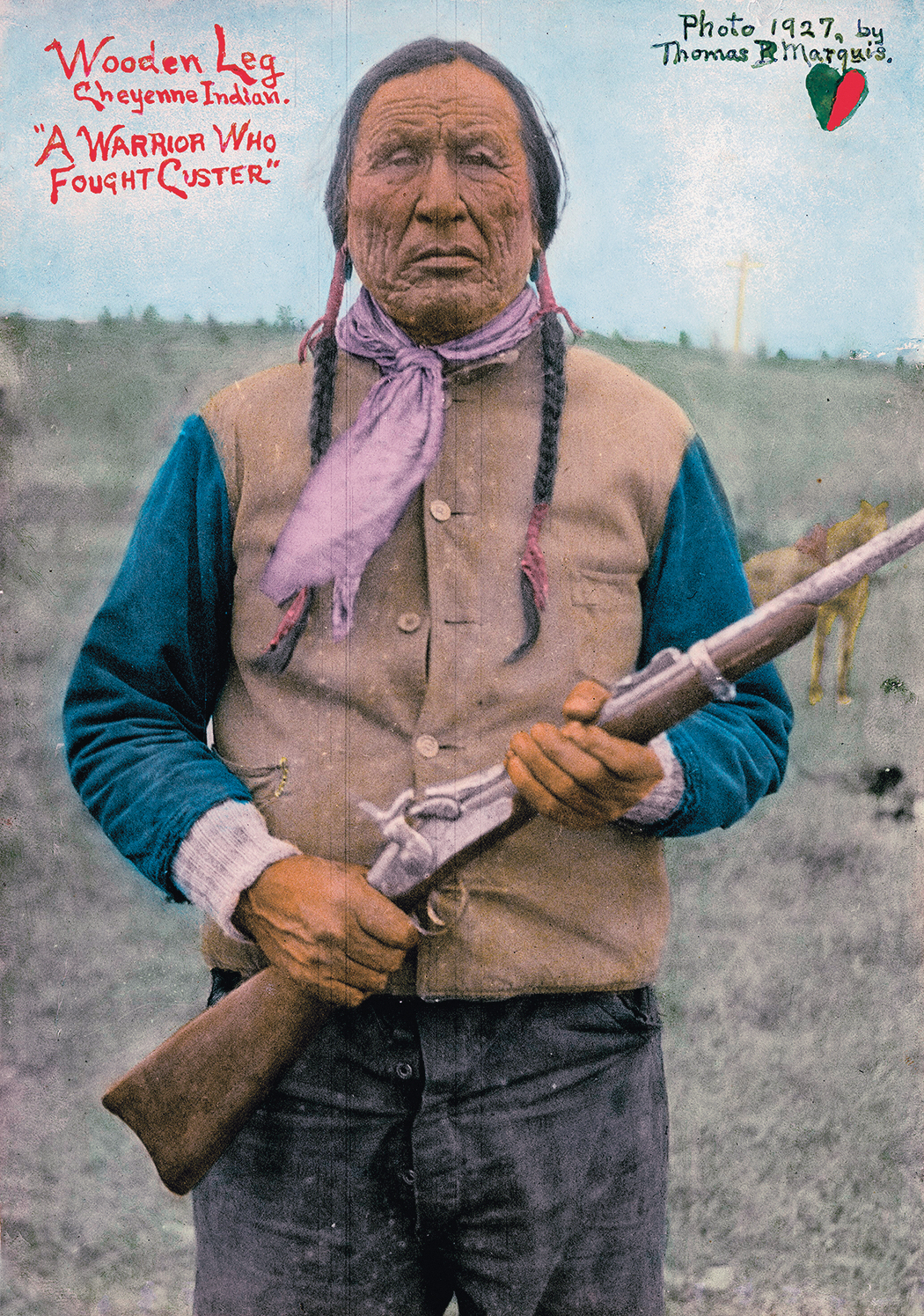

The Trapdoor in Tribal Hands

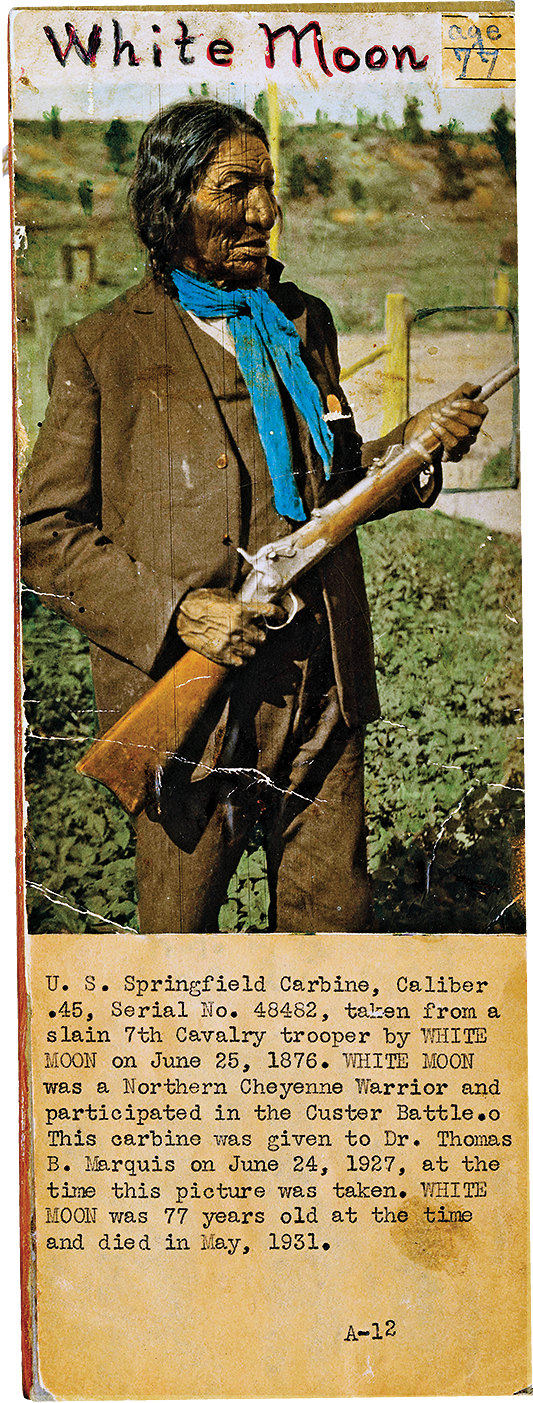

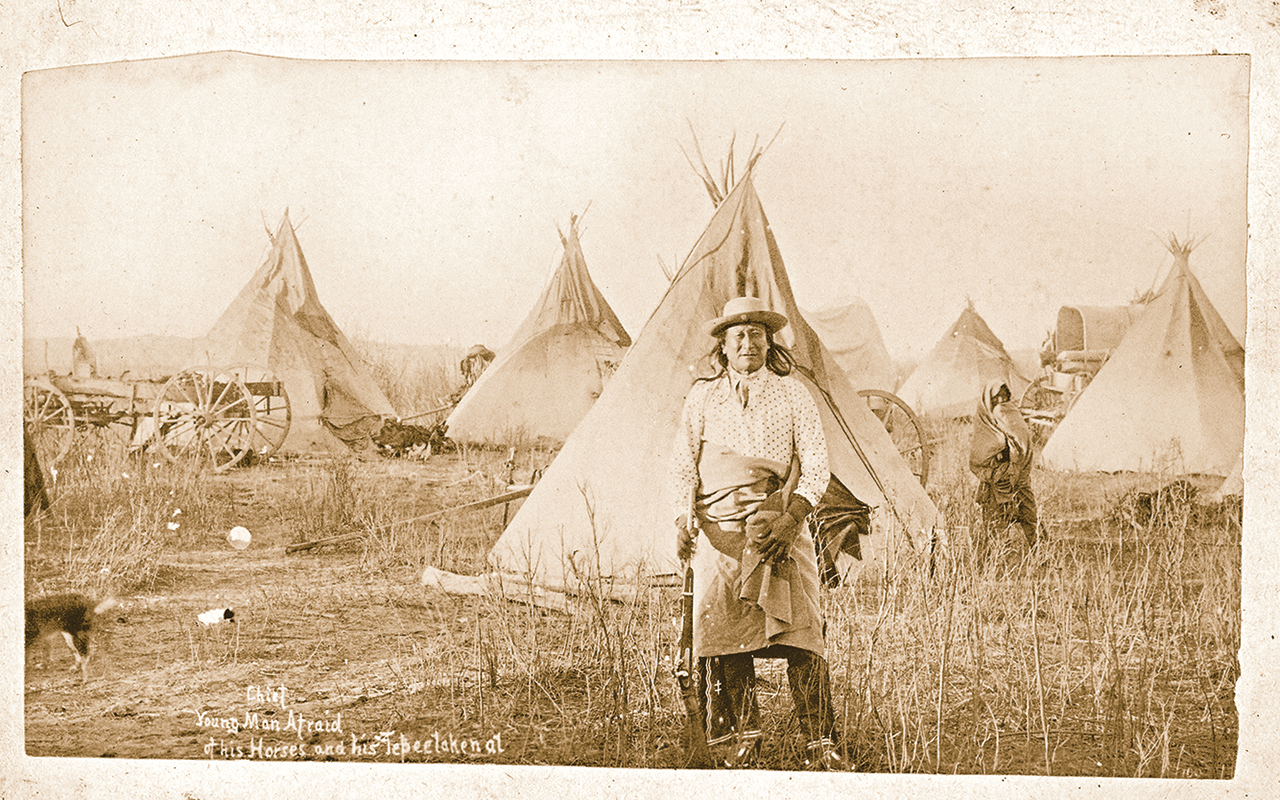

Unlike the troops they faced, American Indians could not look to a central support system for the Springfield and other arms they obtained from the whites through diverse means. This meant that innovative methods of reloading ammunition and maintaining or repairing broken weapons relied on the creativity of each warrior. A fractured wrist of a stock could not be sent back to the arsenal for replacement. Wetted rawhide and perhaps glue made from bison and even a bit of stray wire might be wrapped around the break so the hard-to-obtain firearm could continue in service. Also, because the weapon was not government-issue as it was to a soldier, but instead a personal piece of war regalia, it might be decorated with brass trade tacks, carvings or other additions to distinguish it as the property of a proud fighting man and capable hunter. Proficiency with armaments of many kinds was a given for most tribesmen who gained honor from valor in warfare and raiding as well as protecting their people and providing game to sustain them as a staple of their diets. This is not to say that American Indians were sharpshooters; most had little or no understanding of the use of sights, and accuracy was not very good, especially if fired from a galloping horse or from underneath the animal’s chest as it galloped, which was the practice of many of the Plains warriors.

– All Photos Courtesy Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument Photo Archives, Unless Otherwise Noted –

Reno’s Defense

Midday on June 25, 1876, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer had divided the regiment into three contingents, retaining the main body of five companies under his immediate control and splitting the remainder of his force into two other elements under Maj. Marcus Reno and Capt. Frederick W. Benteen. Reno’s battalion was the first to reach the edge of the Indian camp where he dismounted his men in accordance with US Army tactics of the time. One trooper was detailed to take his mount and three others from his four-man squad to the rear while his comrades, who now were on foot, fanned out with fellow troopers to move forward in single-file toward their objective. Their single-shot Model 1873 Springfield carbines, despite the contention that their cartridges frequently jammed in the breech, performed well. Unfortunately, Reno’s battalion soon stirred up a hornets’ nest of Sioux, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors. Wielding an array of weapons from bows and arrows to war clubs, lances and an assortment of firearms including Winchesters, the warriors repulsed Reno’s attack. Reno would join Benteen across the river on high ground where the retreating survivors holed up for several days, avoiding the fate of Custer and his ill-fated followers, all of whom died after a brief, bloody “last stand.”

John P. Langellier specializes in US military history of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. “Battle Tested, Battle Scarred,” is excerpted from his book The “Trapdoor” Springfield: From the Little Bighorn to San Juan Hill (Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2018).