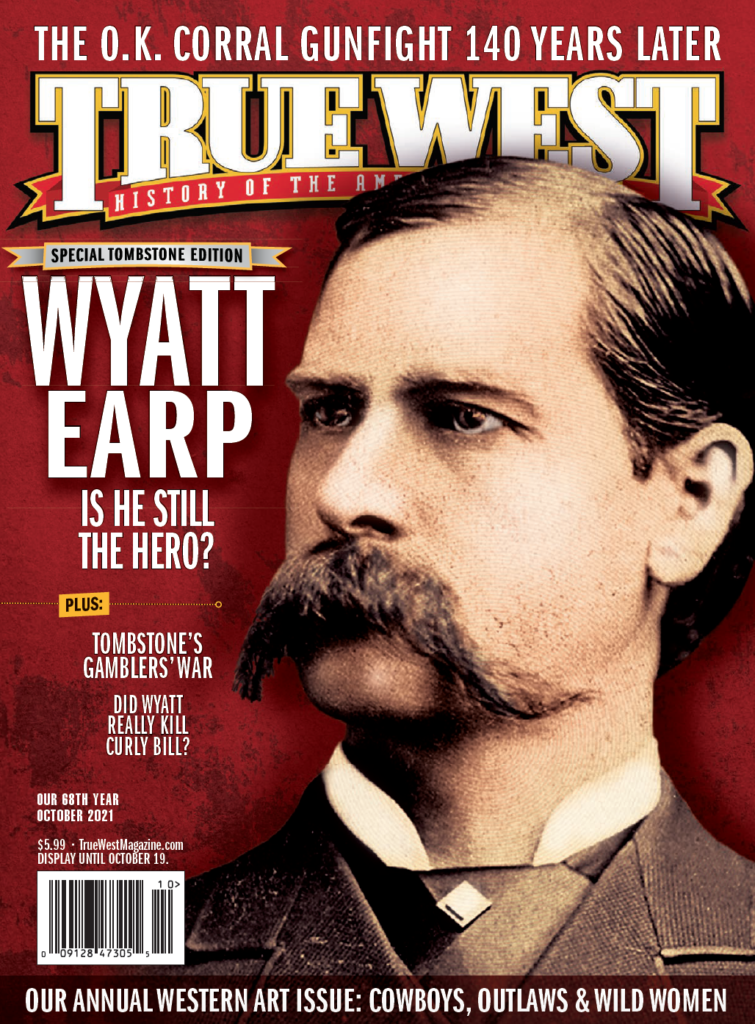

Fighting for the Faro Dollar: Johnny Tyler and Tombstone’s Gamblers’ War

In the summer of 1880, Tombstone, Arizona Territory, was a silver-rich boomtown, and while mining companies and citizens fought legal battles over claim boundaries and town lots, another “battle” would be waged in the saloons and gambling halls. This struggle was between saloon men, professional gamblers and hard cases, all eager to gain a bigger share of the almighty gambling dollar. Gambling was big business in most mining towns, and the sporting men who held their nerve, fleecing miners, cowboys and professionals at their tables, stood to make the lion’s share of the profits.

In late July 1880 the most lavishly appointed saloon and gambling room ever seen in Tombstone was opened to the public by Milt Joyce and his partner, William Parker. The saloon was named the Oriental, and it boasted a polished bar with a chandelier and fine furniture and fixtures. The attached gambling room was carpeted in a plush style aimed to make the clientele as comfortable as possible while they competed with the house. Faro was the most popular card game at the time, and Joyce and his partner offered at least three tables on opening night. The Oriental immediately became the talk of the town, and shortly after its opening night, the Tombstone Epitaph noted the arrival of several new gamblers, referred to as “sporting men.”

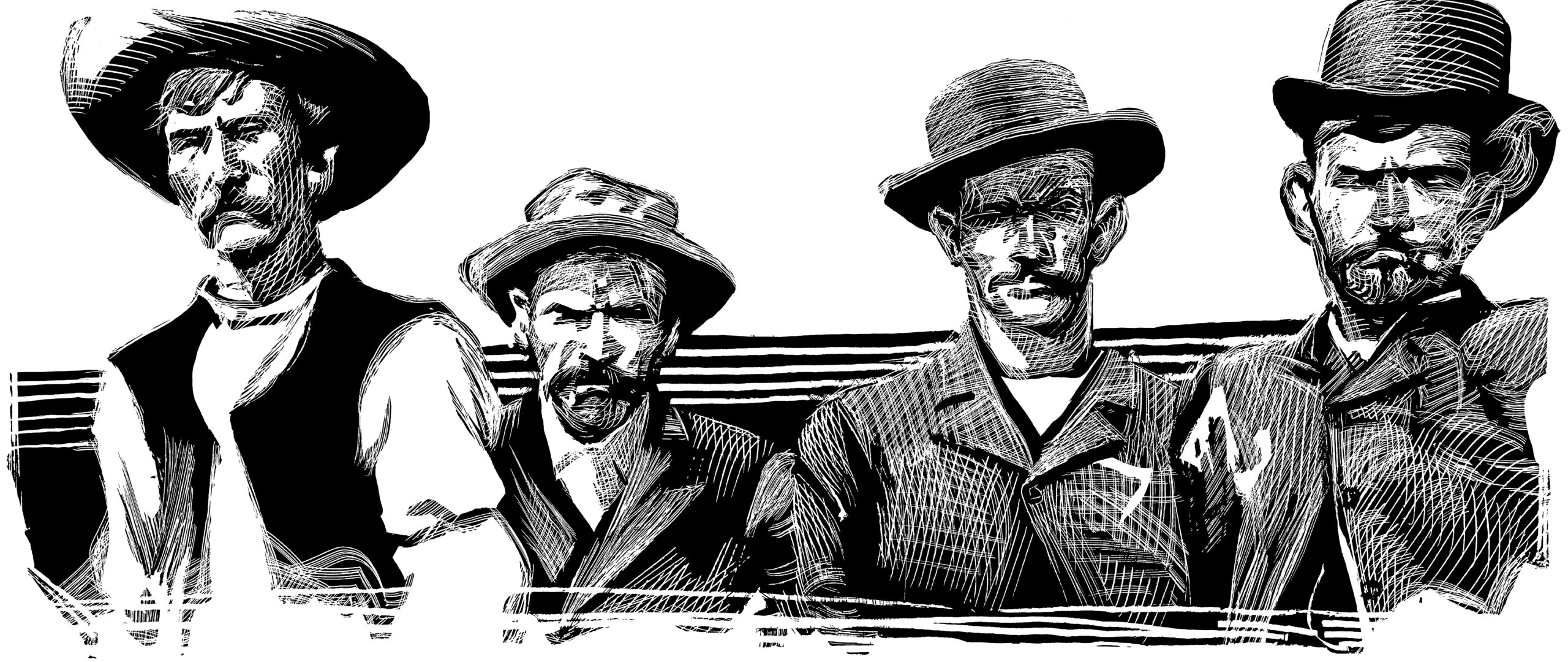

Johnny Tyler was one of these many professional gamblers who had heard of Tombstone’s riches and decided to stake a claim. His arrival just happened to coincide with the opening of the Oriental and would spark ongoing acts of violence that developed due to fierce competition for the faro profits being generated in Tombstone. Disputes between gamblers were not uncommon on the frontier, and in Tombstone, two factions known as the “Slopers,” and the “Easterners” would face off across the green cloth.

Tyler was a certified Sloper. The term was used to describe men who hailed from west of the Pacific Slope and, almost universally, had been schooled in the rough and tumble of the California goldfields, or the bawdy and dangerous Barbary Coast district in San Francisco. These men also frequented the Comstock district in Nevada and were used to gambling against the hardened miners who populated these regions. The other faction in Tombstone, the Easterners, came from east of the Pacific Slope and had dealt faro in Dodge City and the other cow towns of Kansas, as well as larger cities like Denver and St. Louis.

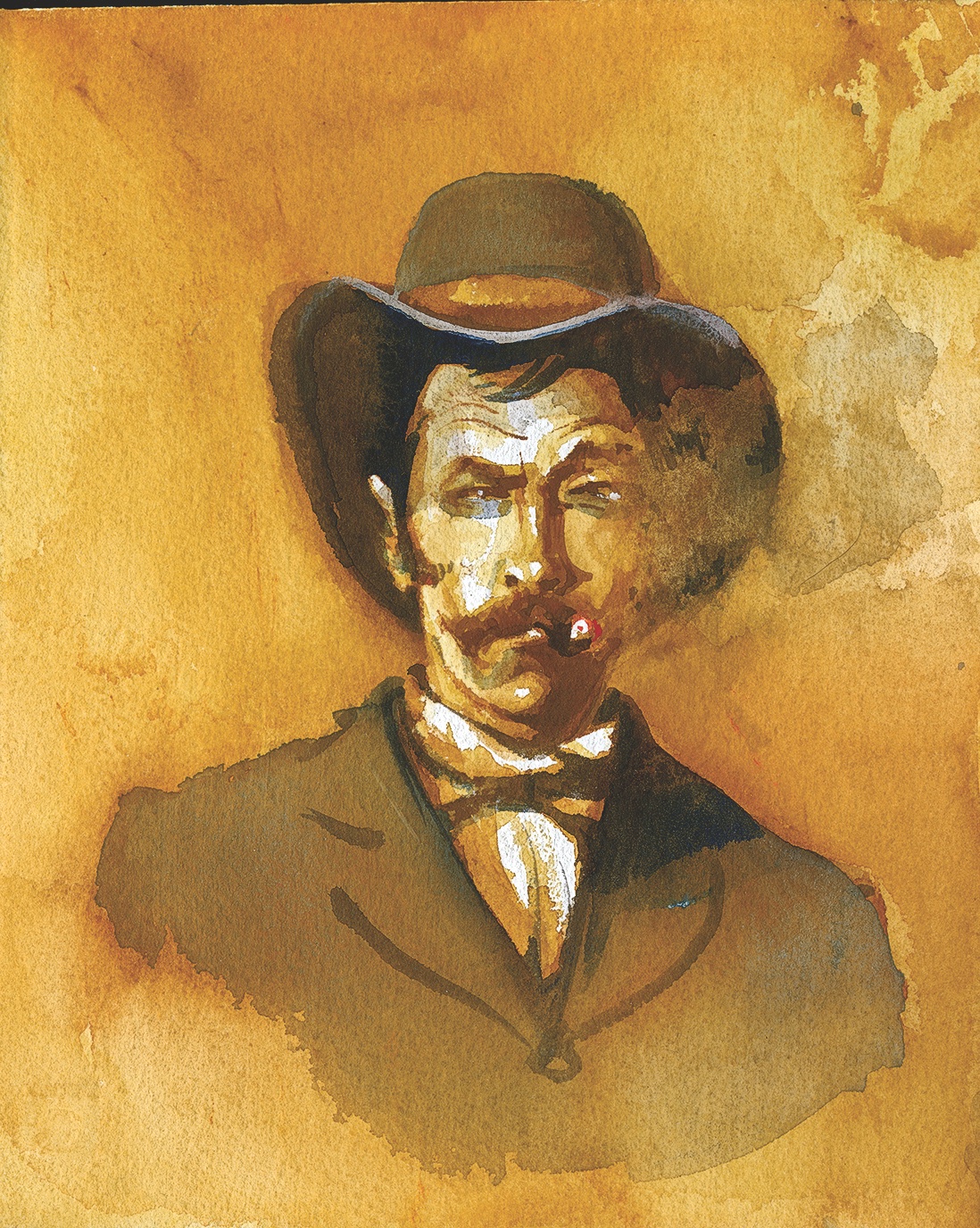

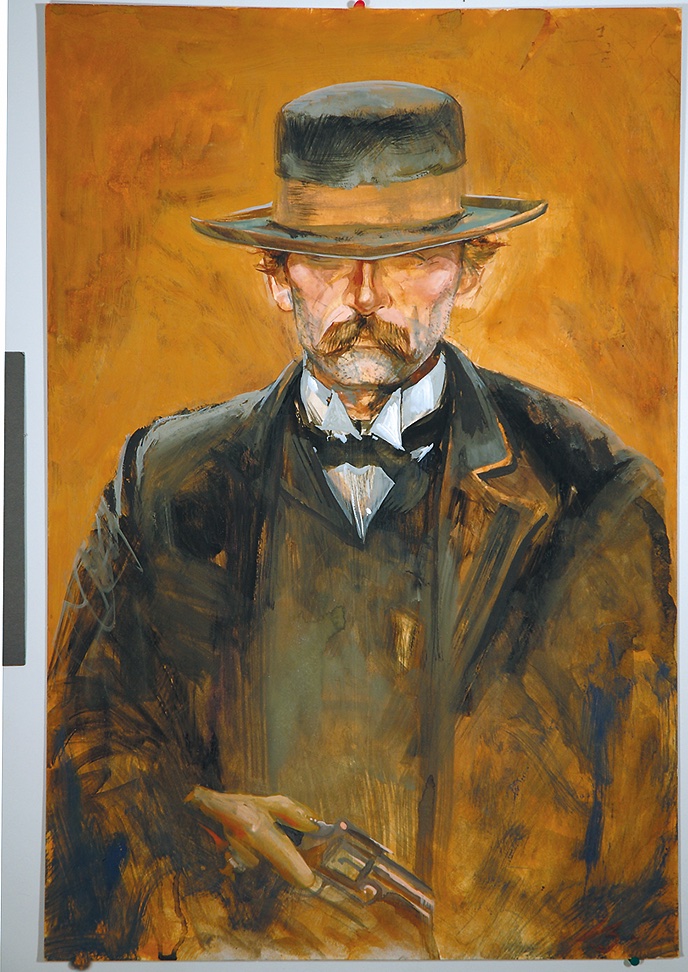

Johnny Tyler was 41 years old when he landed in Tombstone. He had been born in Missouri but raised by his father in the California goldfields, before moving to Sacramento and then to the Barbary Coast. As a professional gambler for twenty years, he had seen and done it all before. In San Francisco, he was noted as a good-looking sport with black hair, a heavy moustache, piercing dark eyes and a fondness for alcohol and swagger. He had shot and killed a fellow gambler in San Francisco during an ongoing disagreement but was acquitted at trial. Seeking to clean his slate, he then operated a saloon and faro table in the fierce frontier town of Pioche, Nevada, before living the high life of a professional gambler in Virginia City.

Tyler’s return to San Francisco in the late 1870s had proved to be unwise, as the local police initiated a prolonged crackdown on faro dens. Tyler’s place was cleaned out and shut down by police in May 1880. All his faro equipment and $1,300 of his money were confiscated during the raid, forcing him to look elsewhere for his action. He chose Tombstone, and immediately eyed off the plush, newly opened, Oriental gambling room. His goal was to open his own faro table or gambling room, but to do so, he needed to put a dent in the competition.

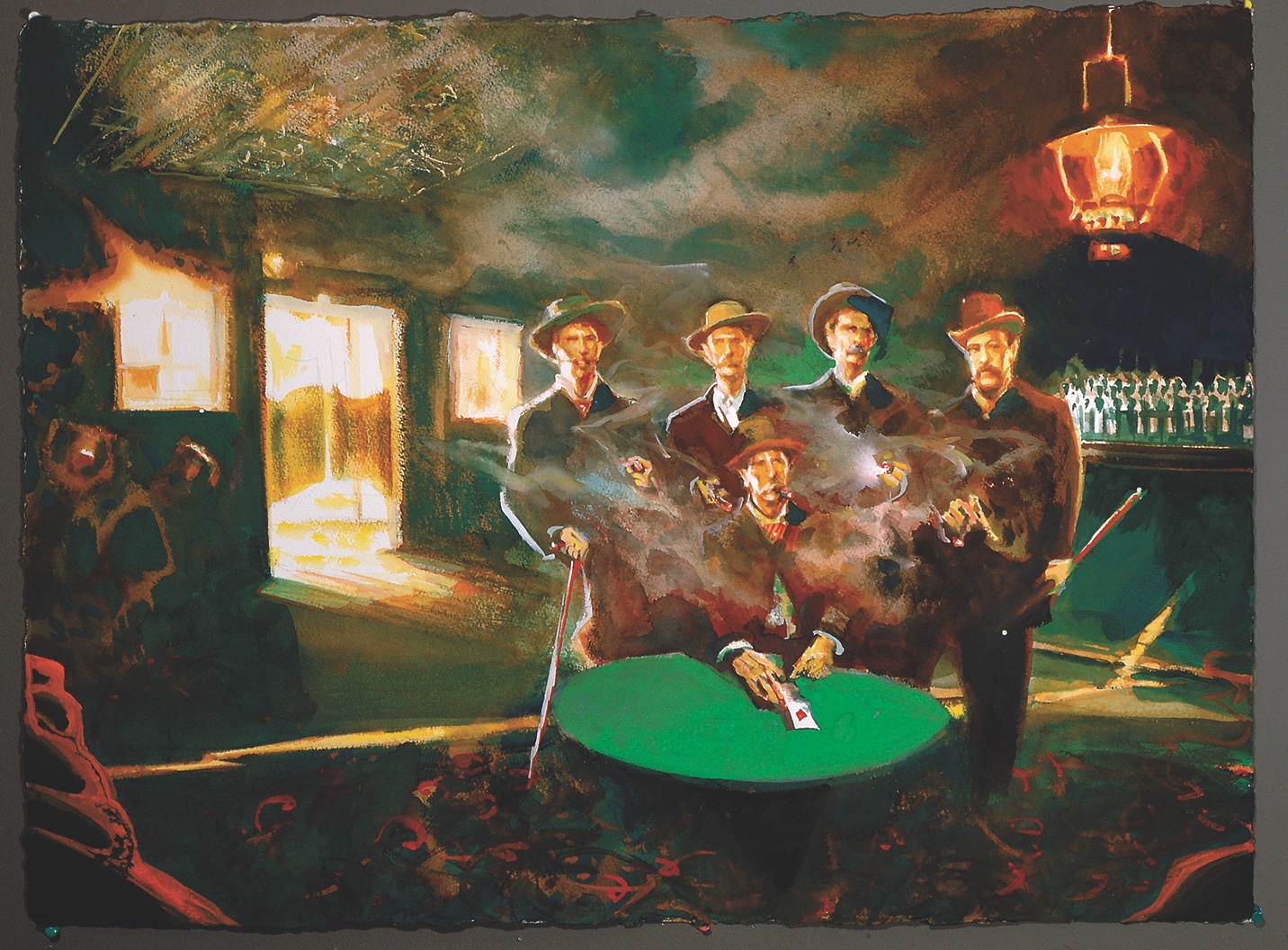

Soon after opening, Milt Joyce and his partner suffered heavy losses in their Oriental gambling room, as professionals, like Tyler, had a run of good luck. Playing faro against the house was commonly referred to as “bucking the tiger,” as a popular playing card of the day featured an image of a tiger on the reverse side. The Epitaph sarcastically commented that the newly arrived gamblers had “skinned the tiger” but allowed Joyce and company to “keep the hide.”

In an attempt to compete with the Oriental’s splendor, the Alhambra Saloon was renovated by its owner, Tom Corrigan. He, too, was eager to attract more gamblers to his three faro tables, but his efforts backfired soon after the reopening of the now grand Alhambra gambling rooms. On the evening of September 21, the available evidence suggests that Johnny Tyler was one of several professionals who took on the house and cleaned out their faro tables to the tune of $1,600. Corrigan put on a brave face, urging the professionals to return, stating “if the boys want more sugar, they know where to find it.”

“Johnny Tyler was generally considered as a gunfighter of the most violent type.” -San Francisco Examiner, 1891

One of Corrigan’s dealers, a former billiard champion named Tony Kraker, was drinking at Vogan’s Saloon two nights later when he clashed heatedly with Tyler. Perhaps gloating over his recent victory at Kraker’s faro table, the always aggressive Tyler went after the hapless dealer. Insults followed, and Kraker and Tyler pulled pistols but were separated by onlookers before any shooting took place. Tyler was warming to his task.

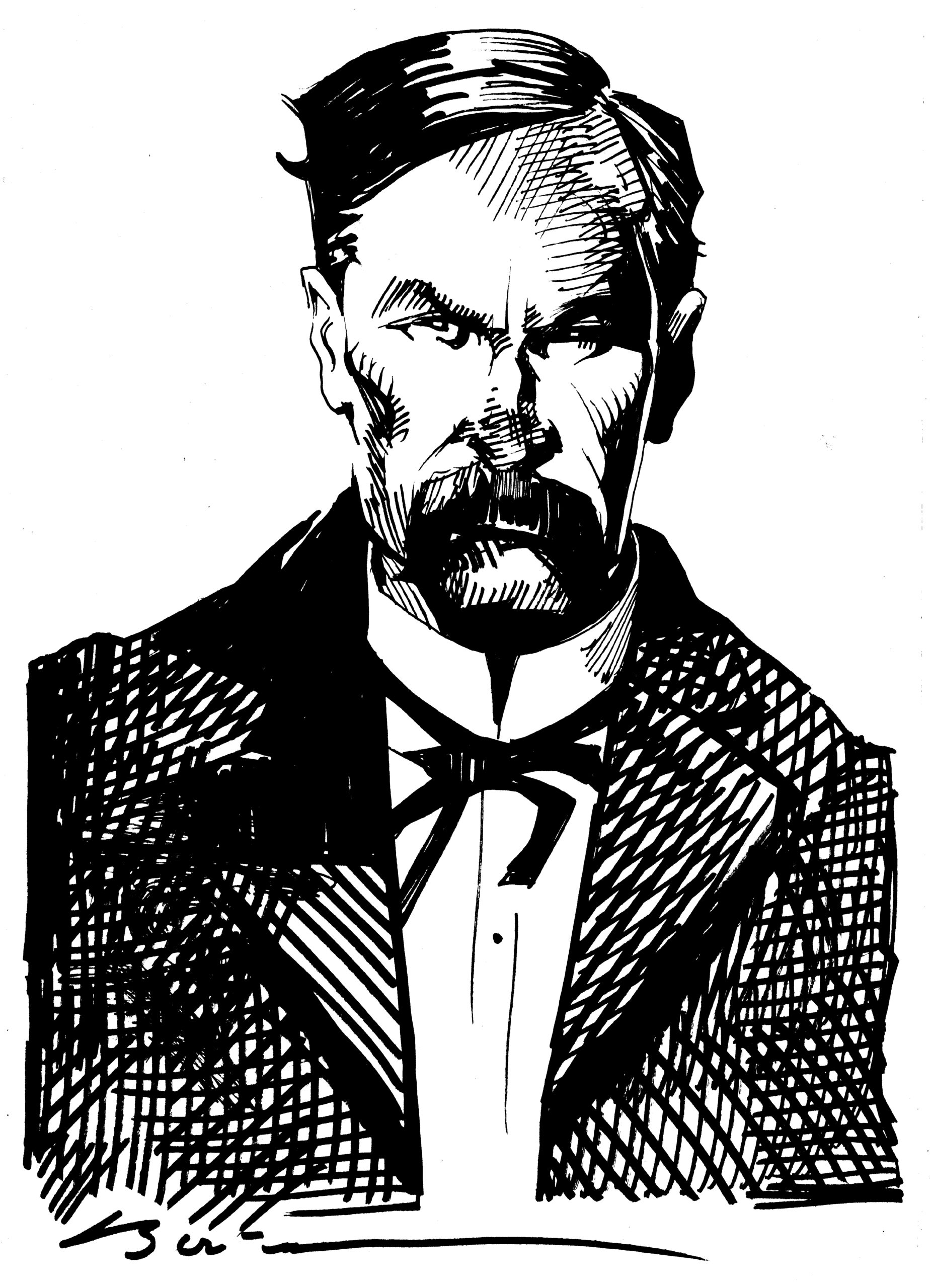

Back at the Oriental, Milt Joyce and his partner must have decided that running a gambling room was not as attractive as they had first thought. On October 1, 1880, they kept the saloon but leased the gaming room to the head of the Easterner faction, Lewis Rickabaugh. He was a seasoned veteran of the gambling circuit, having operated in Denver and more recently in Hot Springs and Little Rock, Arkansas. He was a large, burly gent with deep pockets and a knack for forming mutually beneficial business associations.

All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell and images courtesy True West Archives unless otherwise noted

As soon as he took over, however, violence became a recurring theme at his faro tables. In the first week, two well-known, yet unnamed, gamblers caused a fight that resulted in a third party being bashed with a wooden faro case-keep. Battle lines seemed to be drawn, and Rickabaugh’s rooms were singled out for attention.

The following week, tubercular dentist, Doc Holliday—another newly arrived Easterner—was frequenting the Oriental when he and Johnny Tyler had a disagreement that quickly escalated into threats of a shooting. Holliday was said to have challenged Tyler to a pistol duel, but the two were separated during an exchange of vile abuse. Milt Joyce asked both men to leave in peace. Tyler agreed, but the feisty Holliday returned to the scene, armed and angry at Joyce for interfering in his business. Holliday opened fire and shot Joyce in the hand and his partner in the foot, before the wounded Joyce bashed the dentist into submission. Needless to say, Doc Holliday was no longer welcome at the Oriental, and Tyler was emboldened by the trouble he had helped to create.

October 1880 was a busy month for Tyler. During the third week he achieved one of his goals and opened his own faro table at the Danner and Owens Hall, but he was not finished causing trouble for the Oriental. Evidence suggests that on October 28, he clashed there with another gambler known as “Tex” Hooker. Tyler appears to have been the aggressor as he was fined $10 for disturbing the peace, while Hooker was found to have no case to answer.

Rickabaugh needed to bolster his presence and put an end to the ongoing trouble. To do so, he partnered with two other high stakes Easterner gamblers, Richard Clark and Dodge City’s William Harris. This provided an injection of capital, and, in turn, the powerful consortium employed William “Bat” Masterson and Luke Short as faro dealers at the Oriental.

The Easterner faction were now a force to be reckoned with, and this may have prodded Tyler to seek his own reinforcements in the form of two hardcase Slopers—Charlie Storms and Henry “Dublin” Lyons. Both men were violent gamblers, who headquartered in San Francisco where they knew Tyler, but travelled the West playing high stakes faro in Tyler’s other haunts, including Pioche and Virginia City, Nevada.

They arrived in Tombstone during February 1881 and immediately singled out the Oriental gambling room to cause trouble. Reporting with the benefit of hindsight, the National Police Gazette thought their arrival in Tombstone was far from coincidental and flatly stated that Storms and Lyons were actually fighters for the Slopers and had been imported to disrupt the Oriental and kill Luke Short.

If that was actually their intent, it did not go according to plan. Storms became drunk and aggressive in the early hours of February 25, and began to abuse Rickabaugh, who wisely chose to leave quietly. Storms then turned to Luke Short, but the sober dealer warned him off. Later that day, Storms came back and called Short out for a duel in front of the Oriental. Short was too fast for him and put two bullets into Storms’s chest, leaving him dead in the dust, while his shocked partner, Dublin Lyons, watched on in disbelief.

After seeing to the burial of his partner, Lyons went back to the Oriental to finish the job Storms had started, but he was a man completely out of his depth. Evidence suggests Rickabaugh bashed Lyons in the head with a six-shooter and threw him out. Wyatt Earp, another former Dodge City man eager to join the Rickabaugh consortium, then physically manhandled Lyons and ordered the defeated Sloper to leave Tombstone. As another gambler noted, Lyons “very quietly got up and dusted.”

Johnny Tyler’s position now seemed untenable in Tombstone, but a further seemingly unrelated killing at the Oriental, on March 1, 1881, delivered him a reprieve and a bonus. Two gamblers had fought at a faro table, resulting in yet another death. Milt Joyce reached the end of his patience. He wanted no more violence associated with the Oriental, which was now being described as a “regular slaughterhouse.” Joyce took the drastic action of terminating Rickabaugh’s lease and closing the entire saloon and gambling room for a month.

This was the catalyst that saw William Harris, Bat Masterson and Luke Short all leave Tombstone, while Rickabaugh and Clark scouted for a new gambling venue. Much to Joyce’s dismay, the owners of the block on which the Oriental stood then decided to add a second story to the building, and Rickabaugh, Clark and a new partner, Wyatt Earp, leased the newly constructed premises for their own gambling rooms. They were in direct competition with Joyce, who was situated below them.

The grand opening of the new Rickabaugh club rooms with the usual lavish furniture and plush fittings previously associated with the Oriental occurred on June 11, 1881, and Johnny Tyler was still in Tombstone and was either envious of the new competition, or simply wanted to break their bank, and he wasted no time. On the evening of June 19, evidence suggests Tyler went to the new club rooms intent on causing trouble. Probably drunk, he sat down at Rickabaugh’s faro table and unwisely began to abuse the owner. Wyatt Earp, now a partner, would not tolerate Tyler and immediately grabbed him and threw him down the stairs and out onto Allen Street. Earp bluntly told Tyler that he had a “fighting interest” in the new club rooms and ordered Tyler out of Tombstone.

A San Francisco newspaper later confirmed that Johnny was smart enough to heed the warning. The Examiner reported that Tyler “ran afoul of the Earps. He took a licking from some of them and allowed himself to be driven out of Tombstone.”

Tyler’s exile ended the Sloper-Easterner hostilities in Tombstone, and he moved to Tucson for the next couple of months, before relocating to Leadville, Colorado. But he was not quite done with yet, as fate would see him tangle once again with Doc Holliday in Leadville, and their old Tombstone enmities would violently resurface.

Peter Brand is a researcher and author whose books include biographies of Texas Jack Vermillion of the Earp Vendetta Posse, and Doc Holliday’s Nemesis, The Story of Johnny Tyler and Tombstone’s Gamblers’ War. For more on Brand’s books, go to TombstoneVendetta.com.