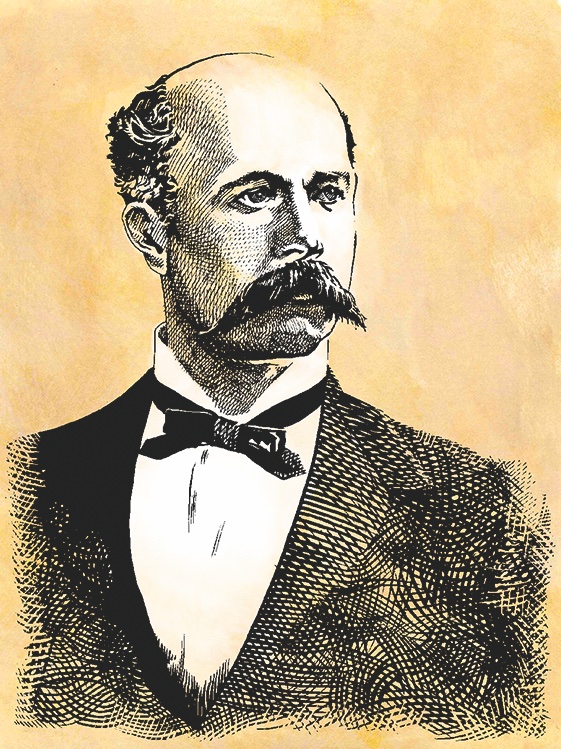

John Clum was busy when the Tombstone street fight took place.

Courtesy True West Archives

It’s entirely possible to get so engrossed in a task that one misses a big story, right in front of them. Take John Clum.

The weather was chilly in Tombstone on the morning of October 26, 1881. Clum, bundled up in his overcoat, walked the few blocks from his home to The Tombstone Epitaph office. As owner, publisher, editor, chief reporter and writer, advertising salesman, etc., most of the burden of getting the paper out fell on him.

He knew he had to be on his toes. Tempers were hot as the law enforcement side of the Earps and Doc Holliday came into greater conflict with the so-called Cowboys of the Clantons, McLaurys, et al.

At around noon, Clum walked to the Grand Hotel for lunch and saw Ike Clanton, who was carrying a rifle: “Hello, Ike! Any new war?” Clum had no idea how prescient that greeting was. There’s no indication Clanton responded as he rushed up the street. Then Clum witnessed Town Marshal Virgil Earp and his brother Morgan head off Clanton, buffaloing him with a pistol and arresting him for illegally carrying a weapon in town. Ike had been threatening to kill the Earps, so they were taking no chances. Clum watched as the lawmen hauled Clanton off to Judge Wells Spicer’s court, where the defendant was fined $25 and released.

Illustration by Bob Boze Bell

Clum was not present a little while later when Wyatt Earp took Tom McLaury’s pistol and hit him over the head with it. The newspaperman was enjoying his lunch, apparently hoping the whole thing would just blow over. Those hopes would be dashed.

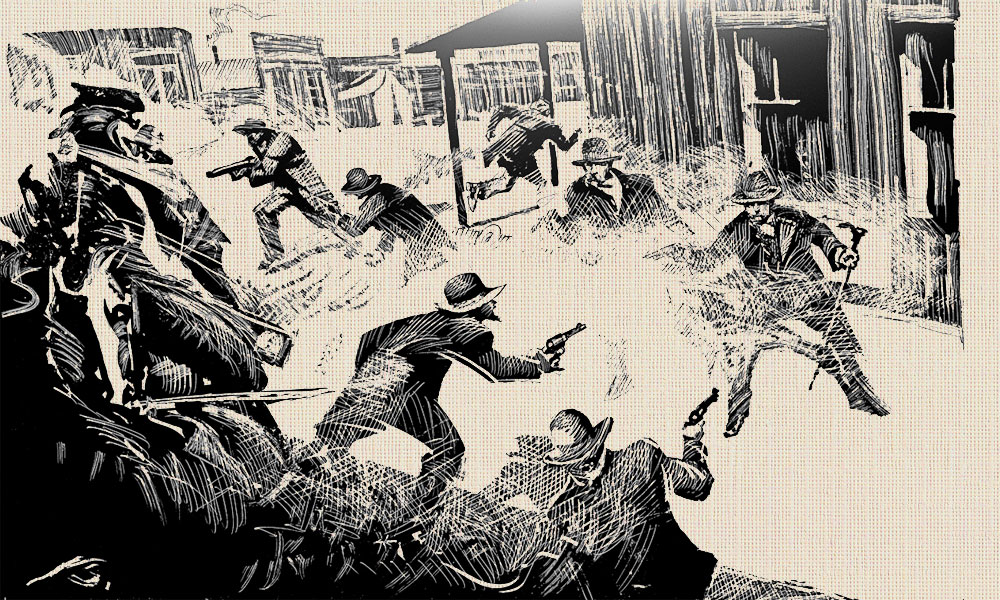

After lunch, Clum got all the details on the earlier events—slanted, of course, since most of his sources were, like him, Earp supporters. He then took all the information and went back to the office. He didn’t see nine men gather in the empty lot that was within view of The Epitaph.

As the guns went off, just across Fremont Street, John Clum was missing the commotion. “I was busy with my story…and did not notice them.” Ironically, his story was about the arrest of Ike Clanton and disarming of Tom McLaury just a few hours before. As he wrote, Ike was running from the gunfight; McLaury would be carried out.

Clum only pulled himself away from his desk when the firing stopped. He stepped outside to take in the situation as dozens of people rushed to the scene. But even more came to The Epitaph. It was prearranged that, in the event of a gunfight, members of the Citizens’ Safety Committee (often described as vigilantes) would gather outside the newspaper office prepared to step in to stop additional violence—and Clum was the head of the committee. Quickly, the force provided bodyguards for the Earps and Holliday and set up guards around town.

For his part, Clum had to switch his many hats. He had a long article to write on the street fight, taking up much of the next day’s Epitaph. As mayor, Clum also had to oversee public safety, including deciding who would be acting marshal in place of a severely injured Virgil Earp. And, apparently, a school trustee meeting was held as planned on the 27th—with Clum as chairman.

Things didn’t slow down. The Spicer hearing was held in the Miner’s Exchange, next door to The Epitaph, and Clum helped cover the proceedings throughout the month of November. And in his various roles, he tried to make sure the town still ran smoothly. It didn’t. Clum and others received death threats—and he survived an alleged assassination attempt in December. By May 1, 1882, two years to the day after he first printed The Epitaph, Clum sold the paper and left the area. For the rest of his life, he would make history but not cover it.