Texas Longhorns were a tough breed of cattle, in a tough place—Texas. And tough were the men that drove them.

Texas Longhorns were a tough breed of cattle, in a tough place—Texas. And tough were the men that drove them.

Two such men, though hardly men at all, had a plan. Young Tom Candy Ponting and his partner, Washington Malone, had heard stories of the availability of cattle in Texas. The durable, hardy Texas cattle were practically running wild and could be bought for next to nothing.

Ponting and Malone would buy, herd and sell cattle, all the time saving their money, so they could ride to Texas and buy Longhorns. They’d drive them to New York—all the way from Texas to New York. It had never been done. The trip would take over a year, so the cattle would winter in the Midwest and fatten on corn. The drive and the corn would turn an “$8- to $12- dollar steer” from Texas, into an “$80- to a $100-dollar steer” in New York.

Young Tom Ponting always planned ahead. Ponting planned to come to the United States from England and work hard doing what he knew best—herding and selling cattle.

But fate played a trick: in 1845, an outbreak of hoof and mouth disease in England, the English repeal of the Corn Laws and the Irish potato blight, all contributed to an earlier voyage than planned. Ponting and his brother, John, boarded the London, embarking on a six-week-trip to the United States.

John remained in Ohio, and Tom continued on to Illinois. There, Tom Candy Ponting set upon new plans. He first met his bride-to-be, Margaret Snyder in Illinois and that day recalled telling her mother “to take good care of her for me, for when she got old enough I was going to try to get her for a wife.” Ponting’s planning often paid off. They were married in 1856.

Malone and Ponting, both young men in 1853, had already saved $50-gold-pieces to use for purchase. Ponting remembered, “It was very disagreeable to carry this gold, but there was no such thing as a draft nor any bank to get them on.”

They carried the gold in buckskin money belts. “These belts,” Ponting recalled, “were wadded with cotton and divided into compartments, so that the gold could not get together. We had our suspenders fastened to these belts and wore them between our two shirts. We never took them off except when we changed our clothes and then we felt very light.”

Ponting and Malone made their first stop in St. Louis. They roomed at the elegant, 12-year-old Planters’ House. It was still winter and the riverfront was lined with steamboats, the boatmen trying to keep their crafts out of the ice. The steamboats caught fire and Pointing wrote, “It was the first great fire I had ever seen.”

After a few days, Ponting and his partner continued on. “Our aim,” Ponting explained, “while traveling horseback, was to make 100 miles in three days. We never stopped for dinner, but had an early supper. When we had to pay at all, it was only .50¢ apiece, this including supper, bed, breakfast and horse feed.”

The young adventurers stopped next in Springfield, Missouri where they had their horses shod and wrote letters to friends in Illinois. They left instructions for the postmaster to hold their mail until they returned or wrote for it.

Pointing and Malone saddled up and rode south from Springfield. A man driving 100 mules to Louisiana rode along with them. This part of the trip was uneventful, that is, until they met a rider who recommended that they stop near White Sulfur Springs in Hopkins County. They stopped, as the stranger suggested, but they soon had regrets. The man of the house, Ponting noted, “[had] the worst case of sore eyes I ever saw. His wife was a younger woman, but she did not look as if she had seen a comb or soap for months.” The children were in the same fix.

It was soon time for dinner and the woman began to fry meat. It was pork and, from the smell of it, uncured. Ponting wrote, “I could not eat any supper but drank some of the spring water.” They got on the trail early—before breakfast. Ponting noted, “I shall never forget White Sulphur Springs.”

Not long after, Malone and Ponting became ill. A family named Clutter put them up. The money they carried was burdensome while they were sick, and Ponting decided to confide in Mrs. Clutter. Ponting explained, “I took Mrs. Clutter aside and told her our business. This was the first time we had ever told what our business was. I asked her if she would take the money and put it under her mattress and not mention it to anyone, not even her husband. She promised me she would do so and we left the money with her, and she kept it safely until we called for it.”

Healthy again and looking for cattle to buy, the partners pressed on toward an area called Honey Grove. There they found a family with several hundred log hives of bees. Pointing wrote, “I went into the house and found honey on everything, on the chairs, tables and on the children’s hair. Since then, I have never cared much for honey. It was too much of a good thing.”

Pointing and Malone added an elderly gentleman to their adventure. His name was James Byers and he was homesick. He’d seen all of Texas he wanted. He longed to return to Illinois and wanted to go east with them.

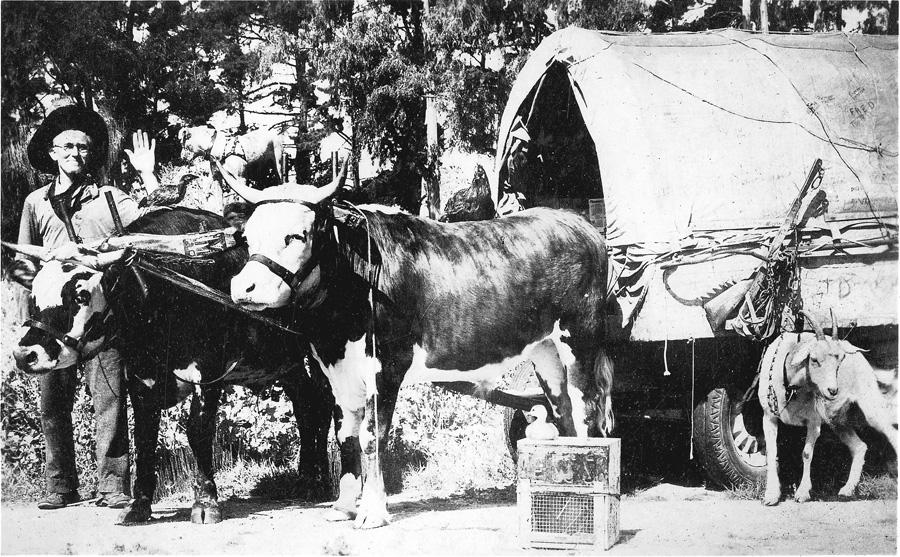

There was only one stipulation: don’t let him drink, his daughter insisted. Ponting agreed and they hired Byers as their cook and ox-team driver. “We bought a wagon and some canvas to cover it and to make a tent out of. We also bought a yoke of oxen to haul our wagon.”

It was time to begin buying cattle for the trip east. Malone and Ponting met Merida Hart who offered to take them to a neighbor who had cattle to sell.

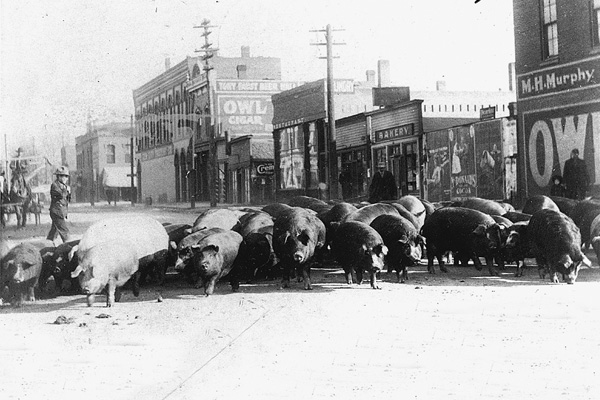

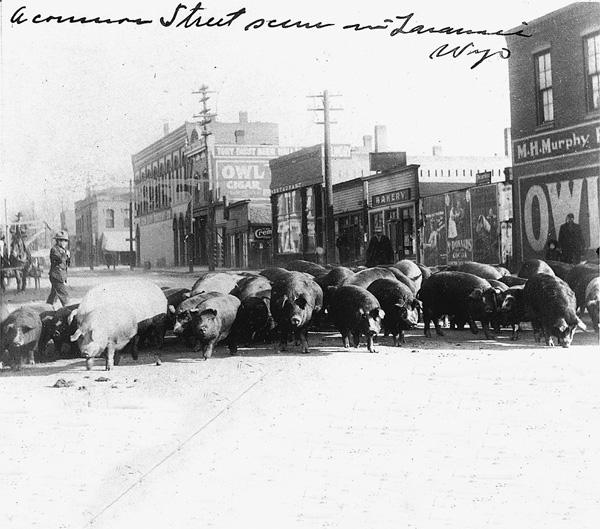

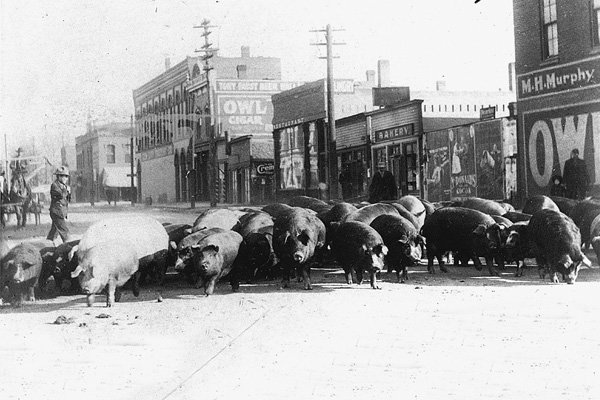

Hart was curious as to Ponting’s methods. Ponting explained that he would not only drive cattle, but hogs. Ponting said they’d feed them corn and “would have about three hogs to every two steers to pick up the droppings.”

Hart asked what droppings were. Ponting answered, “After the cattle would eat the corn, what passed through them the hogs would eat and get fat on.”

Hart scratched his head and remarked, “Well, I have heard you Yankees were very close people, but I did not suppose you were so close that you would try to fatten hogs on the same feed as the cattle.”

Ponting met other families, too. One named Conan claimed to be wealthy but offered only cornbread baked several days earlier with jerked dried beef. Ponting said, “I thought I did not care to be rich if that was how one had to live.”

Another Texas cattleman told how the area was getting overpopulated. The man complained to Ponting that he had three neighbors within 20 miles.

Despite the wild and woolly country, Ponting noted, “As new as the country was I was treated very well; no man spoke an angry word to me. If I went to a place where anyone was drinking, I always left.”

From Hopkins County, Malone and Ponting rode north toward the Red River and across into Indian Territory. Ponting wasn’ t quite sure what to make of things in Indian Territory.

In his lifetime, Ponting never felt the need to carry a gun. He considered himself a man of peace. So, how did he deal with the threat of the theft of his cattle? He sat his horse all night long through Indian Territory. All in all, the partners had more trouble fording treacherous rivers than they had with cattle thieves.

All together, Ponting and Malone bought about 700 head of Texas cattle. Eighty of those were “fine steers” that weighed about l200 pounds. He gave $9 a head for them.

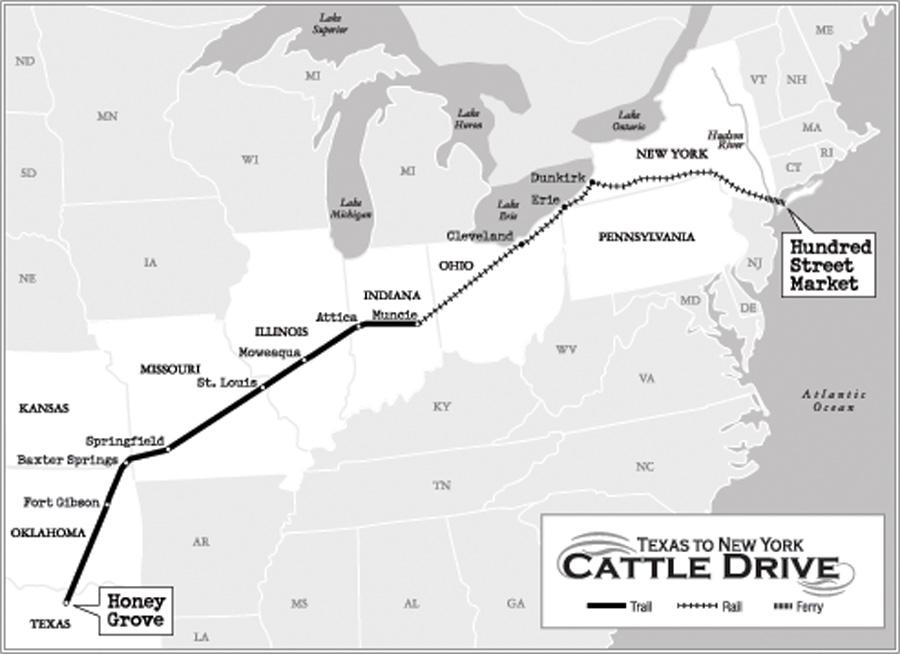

They drove their cattle past Fort Gibson near present-day Baxter Springs, Kansas, then into Missouri and on to Springfield.

The trail from Springfield to St. Louis was friendly. Folks gave them butter, eggs and bacon. They charged nothing, saying, as Ponting recalled, “there was no market for them and that we were perfectly welcome to them.”

Their clothes were nearly worn out by the time they returned to St. Louis. There they bought some “store clothes.” Ponting mentioned that he’d worn one shirt for six weeks. “When I wanted to wash it I took it off at night, tied it in a stream, and the next morning wrung it out and hung it up to dry, then put it on and would probably forget to wash it again for two weeks.”

Ponting said they crossed the cattle at St. Louis to “the other side of the river, where East St. Louis now is.” Byers, their cook and ox-wagon driver, left for his home in Greene County, Illinois north of St. Louis. They continued on, and by July 26, 1853, they were within five miles or so of Moweaqua in Christian County, Illinois.

Malone and Ponting made preparations to winter the cattle in the Christian County area. Washington Malone took ill, and there was trouble finding someone to help Ponting with the cattle. James Jacobs finally came to his aid. Ponting wrote later. “It took considerable work to prepare a place to winter so many cattle; we had to buy a great deal of corn. We kept some on feed for fattening, and others we put out in different bunches to be fed for the winter on rough feed.”

There was an early spring in central Illinois in 1854, so many of the feeding problems with the herd were averted. Ponting sold some of the cattle to a man from Ohio. By the time he was ready to begin moving the cattle toward New York City, Ponting had cut the herd to 150 head. He and Malone drove them into Indiana and crossed the Wabash River near Attica.

There was concern about driving the cattle across the Wabash, but they put the oxen on a ferry, and the cattle waded off into the water and followed it. On the other side of Indiana at Muncie, they put the cattle aboard a train. Ponting arranged for the train to stop every now and then so that the cattle could graze. Ponting unloaded the cattle at Cleveland, then reloaded for a run through Erie and Dunkirk on the Erie road. They grazed the cattle at “Harnesville and then at Bergen Hill” just across the Hudson River from New York City.

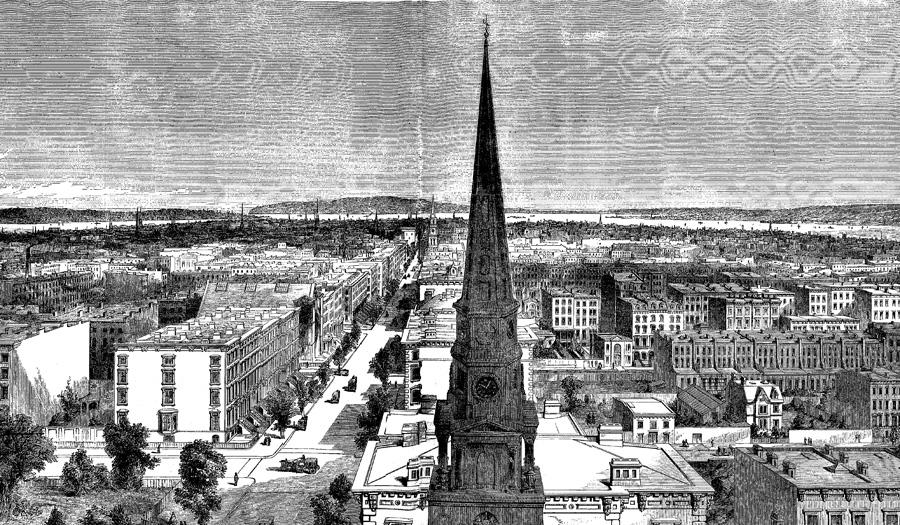

Soon Ponting and his Texas Longhorn herd began loading onto the ferry, proceeding across the Hudson to the Hundred Street Market. On July 3, 1854, Ponting found a salesman named James Gileris (Gilchrist) and “told him not to turn a bullock out of the yard until they were all sold, and not to tell where the cattle were from.” Ponting recalled, “The butchers thought because they had such long horns they must be from Iowa. These were the first Texas cattle that were ever in New York.”

The Tribune reporter described the herd: “These cattle are generally 5, 6, and 7 years old, rather long-legged, though fine horned, with long tapered horns, and something of a wild look.”

The next day, July 4, 1854, the New York Daily Tribune reported that 130 head of cattle from Texas were in the “New York Cattle Market” the previous day. The report said the cattle were from Fanning (Fannin) County, Texas and brought “by T.C. Ponting of Christian County, Ill., and W. Malone of Vermilion Co., Indiana.”

The reporter figured they brought the cattle “about 1,500 miles on foot and 600 miles on the Railroad. The expense from Texas to Illinois was about $2 a head, the owners camping out all the way. From Illinois here the expense is $17 a head. The drove came 500 miles through the Indian country.”

Concluding, the Tribune writer wrote: “The owners are two young men, who are entitled to considerable credit for their enterprise, as well as bringing the first drove of cattle from Texas to the New York market. They first earned the money to purchase, and have done nearly all the work themselves, and will make a handsome thing of the enterprise.”

Ponting returned to Illinois. Modestly, he concluded. “The partnership between Malone and myself ended satisfactorily.”

Life after New York City may have not been as exciting, but it was as profitable. Ponting, operating from central Illinois, drove cattle to Canada and midwestern cities like Chicago and Milwaukee. He shipped cattle by rail from Abilene, Kansas, and Colorado, to Albany, New York, and abroad to Holland and Great Britain. The enterprising Ponting also imported Shorthorn and Hereford stock from Holland and Great Britain.

Dubbed by many “The Cattle King of Central Illinois,” Ponting’s children began encouraging their father to retire the year of his 80th birthday. So in 1903, Ponting sold his house and land and moved to town.

In the years that followed. Ponting and his wife, Margret, traveled a great deal. Their travels included a visit to his former home in England. He and Margaret traveled to Oregon, Washington, California and points in between.

Still busy in retirement, his children suggested that he write his memoirs. The result was the 102-page, 1907 publication of Tom Candy Ponting: An Autobiography.

In August 1916, Ponting became ill. He slipped fast and died at Decatur, Illinois, on October 11. He was 92 years old. He had counted among his friends Montgomery Ward, Potter Palmer, Horace Greeley, Buffalo Bill Cody, P. D. Armour, P. T. Barnum, John Clay, Alexander Swan, and Abraham Lincoln.

A few years before Ponting’s death, a local reporter wrote of him: “He has ridden horseback more than any other farmer in the state, has bought and sold cattle from coast to coast, but he knows nothing of work on the farm. He has been a stock man, that ever since he was a boy in England, and has never been a farm hand.”

Larry D. Underwood is a freelance writer who has published many articles with True West.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Author’s Collection –

– Denver Public Library, Western Collection –

– Author’s Collection –

– True West Archives –