Although director Arthur Penn made only three Westerns, his ranking is secure as one of the genre’s greatest interpreters.

Actually, Penn’s first feature film was a Western. Penn cast newcomer Paul Newman as Billy the Kid in The Left Handed Gun (1958), a misnomered film (the Kid was actually right-handed) that many feel qualifies as the first “revisionist” Western, years ahead of its time.

Penn’s film was an odd combination of the more literate and sociological type of TV drama that was common at the time and the Western, which was entering its peak TV period. He and author Gore Vidal were anxious to say something interesting about media and mythmaking, as it applied to Billy the Kid in his day, and as it existed in the first great decade of TV celebrity. In a way, the film is an interesting companion piece to Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd (1957), which dealt with similar issues.

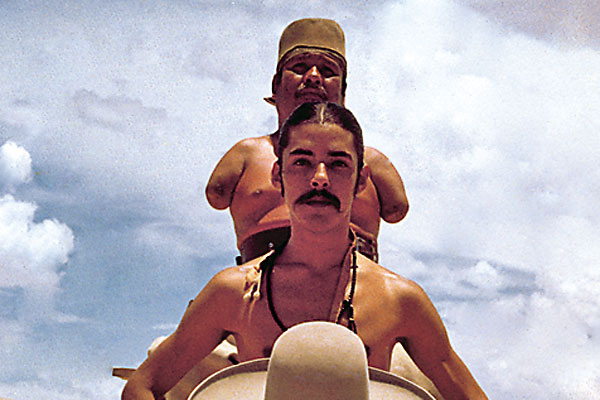

Twelve years later, Penn directed Dustin Hoffman as Jack Crabb in Little Big Man (1970), based on Thomas Berger’s novel, which still shows up in many critics’ all-time favorite Westerns lists. This outrageous comic spectacle, a completely reconfigured version of the mythical West, is told from the perspective of a 121-year-old white man who lived a great part of his life among the Cheyenne but who also operated as a gunslinger, mule skinner, scout, drunk, snake oil salesman and boy toy. This tremendous political satire premiered when even the hardest hawks were beginning to grow disillusioned with the war in Vietnam.

Penn’s final Western, The Missouri Breaks (1976), paired the recent best actor Oscar winner Jack Nicholson (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) with the original bad boy of cinema Marlon Brando. As the hired assassin Robert E. Lee Clayton, Brando took an obvious delight in making the bulky and effeminate Clayton a bizarre, and thoroughly despicable, figure. Nicholson, meantime, played the leader of a gang of horse thieves who saw his friends being picked off one at a time, as his era was grinding to an end. The movie, a good one when it premiered, keeps getting better with age.

Arthur Penn talks to us just as Warner Brothers releases two slightly different two-disc editions of Bonnie & Clyde (1967), which is certainly Penn’s most famous film. The second disc in both cases contains a considerable amount of bonus material, but the “Ultimate Collector’s Edition” also contains books, press kit reproductions and other goodies. About the only thing missing is a vocal commentary track by Mr. Penn and the usual scholars. When I asked him why he wasn’t making an appearance on the disc, he replied, “They didn’t ask me!”

TW: I was just watching The Missouri Breaks and Little Big Man on TV a few days ago. It seems your pictures run on cable frequently nowadays.

AP: I think so. Keep them coming!

After watching The Missouri Breaks, Bonnie and Clyde and Little Big Man, I noticed the theme of innocence often appears in your pictures.

And evil. I think Brando’s character, for example, in The Missouri Breaks, is the quintessence of evil. He’s brought in to just do gratuitous killing with people he doesn’t even know.

Like Chigurh in No Country for Old Men; he’s a force of nature.

Exactly. Yeah, I think that’s true. He is evil personified.

Brando did a great job.

Didn’t he? I thought so.

At the time, some thought he was being indulgent in the part, but I get the feeling he was doing exactly what you wanted.

Exactly. We knew each other well because we’d done The Chase together years earlier.

An actor I know thinks that in The Missouri Breaks and Superman, Brando is in his Claude Rains phase.

Well, he’s doing a whole bunch of people. That was the whole point. We started looking for a character, and we looked at four or five, and I said “why don’t you do them all so we never know who you are.” And that’s what stuck.

The one time Brando’s character speaks without affectation is in the scene when he kills Harry Dean Stanton. It’s actually touching.

I think so. It’s also at the end of his killing.

Was there ever anyone who looked more authentic in a hat and moustache than Harry Dean?

No. Nobody. He’s wonderful. And he’s a wonderful actor. Just terrific.

Something I noticed in Little Big Man is that, for once, Dustin Hoffman is the straight man; a passive observer.

He’s being tossed around by the crazy nature of history, of the events of that period. You know, you of the West know that well.

You directed your first Western, The Left Handed Gun, right at the time when the Western was a huge TV genre. Seems like an interesting moment to be making one of the first anti-western Westerns.

It certainly was. We were not gonna make a Western per se. We were operating on the thesis that what was happening in the West was being exploited by the yellow press in the East when they were publishing early scandalous writing and making, in fact, the people out in the West into heroes. And that was where the development of Billy the Kid came from. It didn’t originate with Bonney out there; it originated with the versions as told by the yellow press. That’s what the Hurd Hatfield character is in The Left Handed Gun. He comes out adoring Bill Bonney and then, by the end of it, feels betrayed by him and, consequently, betrays him.

These characters cared a great deal about how the press depicted them.

Yeah, exactly. That’s what Faye Dunaway’s—Bonnie’s—poem was designed to do [in Bonnie & Clyde], to celebrate them. And she sent it to the newspapers.

They certainly had a desire for fame. Most antisocial guys, gangsters, murderers, even rapists have a desire to be recognized, and I think that’s what went on with these people to a degree.

Which calls into question, the nature of fame.

It certainly does. A very dubious state, I think.

And still, you played in that sand pit?

I can say, not entirely willingly, and I’ve never really quite accepted it.

Your fame, or the fame of those you worked with?

My own fame. The people I worked with deserved their fame. They were actors who wanted to be recognized and known. I was rather less desirous of prominence.

But you earned your fame as well. I remember as far back as Mickey One. Your work separated you from many directors and gave you a degree of creative freedom.

That was the intention. I’d had enough already of orthodoxy and I wanted to kick up my heels. I thought we needed a dose of the freedom the Europeans had.

The work you were doing then worked its way into Bonnie & Clyde.

Yes it did. [Robert] Benton and [David] Newman wrote that and brought it to Francois Truffaut who was interested and then not interested. He suggested Jean-Luc Godard, who said he’d make it in two weeks, which scared the hell out of them. So they showed it to Warren Beatty, who read it and bought it.

Seems like being in New York at that time must have raised your cultural antennae quite a bit.

It was raised more by what the French were doing, the Italians. Bergman and Fellini and the Nouvelle Vague in France. Godard, Resnais, Truffaut. A bunch of great filmmakers.

A great time.

It really was. There was a lot of post-war energy about it. A lot of the feeling, both in live TV and those early films, was, “you ain’t gonna tell me how to do this, no way. I’m going my way. I survived the war, I’ll do it my way.” It was a lot of arrogance that seemed to fit the new technology of TV. And, consequently, the damage that TV did to the movies, that made the movies come looking for the guys who had done TV. That’s how so many of us from the live TV world ended up making our first films in the latter sixties.

Frankenheimer, Altman—

Mulligan, George Roy Hill and so on.

You were a subversive bunch.

Sure, cause they didn’t know what they wanted! We knew that they were going to come up with the conventional, and we were going to go the other way! (Laughs)

We’ve been debating—is Bonnie & Clyde a kind of Western?

I would say it is a Western. One of the characteristics of it is, they’re redefining the law in their own terms. One can assume, as actually took place, that their own family’s homesteads were foreclosed by the banks. Well, that’s very like the old cattlemen-sheepmen stories of the West.

Here’s a bunch of guys coming in wanting to redefine that law in their own terms. So I would say it has all the characteristics of a Western. It just has a little of the specificity of the Midwest because of the automobile.