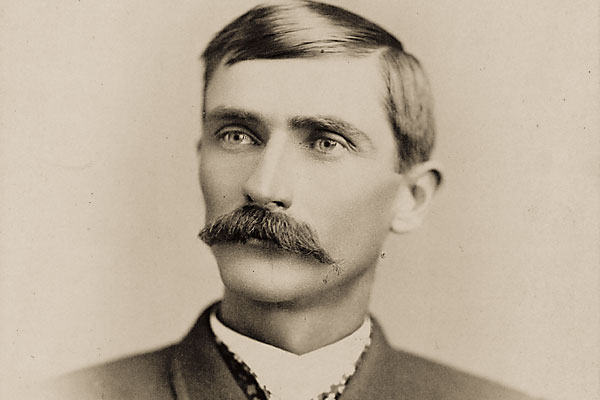

Theodore (“Don’t call me Teddy!”) Roosevelt earned lasting fame by charging up a Cuban hill in 1898.

His greatest legacy in this country might be a big hole that he first visited in 1903.

Yes, the hill and the hole are related.

Roosevelt became fascinated with conservation and the West as early as the 1880s, when he spent an extended period in the Dakota Territory. By 1887, he was working to preserve Yellowstone, and his conservation efforts continued for the next 15 years. His Spanish-American War exploits made him a national hero, which he used as a springboard to the vice presidency. When President William McKinley was assassinated in 1901, Roosevelt moved into the White House and had the “big stick” necessary to save some of America’s greatest natural treasures.

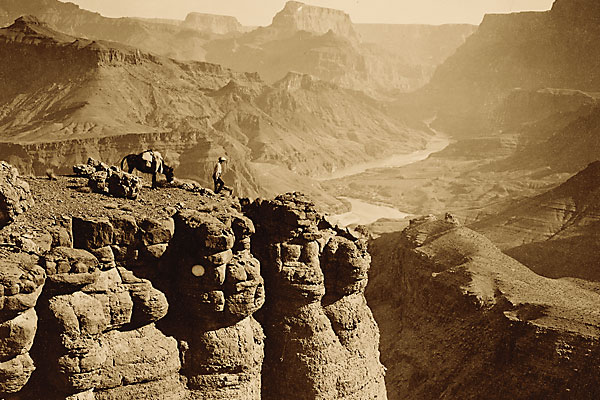

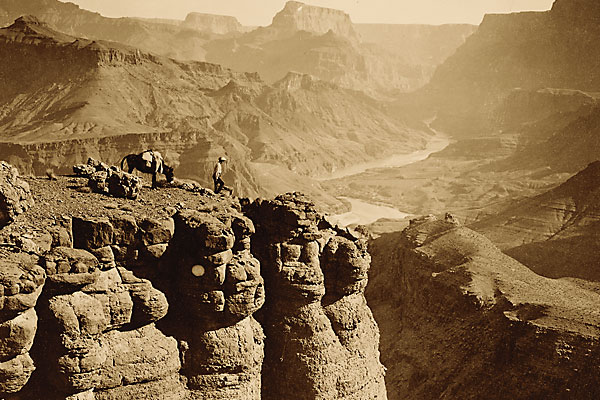

In the summer of 1903, Roosevelt went on a grand tour of the American West. He wanted to see some of his favorite places, including Yellowstone. He also wanted to visit some new wonders—and the Grand Canyon was at the top of the list. He spent a day in May at the canyon, greeting state officials, meeting with his old Rough Rider comrades and taking in the majesty of the great gulch.

His comments to the crowd indicated his future course regarding the canyon: “Leave it as it is. You can not improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it. What you can do is to keep it for your children, your children’s children and for all who come after you, as one of the great sights, which every American, if he can travel at all, should see.”

Yet the effort to preserve the canyon would not come soon or easy.

All sorts of developers wanted to build in and around it, and they blocked attempts by lawmakers to set aside the area. So in 1906, President Roosevelt declared portions of the canyon to be a federal game preserve—which prevented construction in those areas. In early 1908, he went a step further, designating the site as a national monument.

Even after he left office the next year, he used his bully pulpit to promote additional protections. Roosevelt lived to see the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, but he died just six weeks before the Grand Canyon was designated a national park in February 1919.

What would his reaction be to today’s park? Probably mixed. He’d be amazed by the size of it, which expanded to more than 1.2 million acres in 1975. He’d be shocked that more than 4.4 million people visited the Grand Canyon in 2007—as compared to 44,000 in 1919. He’d likely be pleased that more than 340 park structures are on the National Register, with another 44 under consideration.

T.R. would probably cry “Bully!” about the Colorado River’s man-made, controlled flood in early March, aimed at saving some endangered animal and plant species and rebuilding sandbars that were common camping places in his time. He’d enthusiastically back the archaeological and geological studies that continue in and around the canyon—one of which recently concluded that the ditch might be 17 million years old, up from the previous estimates of five to six million (the dating numbers are highly controversial).

Would he be thrilled by the Skywalk the Hualapai Indians built, jutting out of the West rim and allowing visitors to look straight down to the canyon floor—or the $25 ticket cost? Come to think of it, what would he think about entrance fees to national parks in general?

He’d also probably be annoyed by the noise and pollution created by thousands of cars and buses and helicopters and airplanes that regularly enter park space.

Even so, the Grand Canyon is remarkable. Roosevelt’s words in 1903 are as true today as they were then, that visitors will enjoy “…the wonderful grandeur, the sublimity, the great loneliness and beauty of the canyon.”