Hidden among Picassos, Duchamps and Matisses collected by Earl Horter is a fire-hardened buffalo hide shield with an antelope hide strap sling.

At the Philadelphia Museum of Art, though, we are “mad about modernism,” completely unconcerned by any Indian relics thrown in with the rest of the collection. Yet the 1999 catalogue will need to mention something about these “others.” Oh, yes. Have that guy who is always fiddling with our Charles Stephens Indian art collection write it up for us. He’s over at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Go find him.

Enter William Wierzbowski. Plains Indian culture fascinates him. Early Philadelphia collectors of Indian art are his specialty, so he’s up to the task of seeing what Horter amassed. When he comes across a Comanche shield, he reads the accompanying notes, in which Horter mentions … Stephens?

William can hardly contain his excitement. He is ecstatic. He’s intoxicated by joy. And when he confirms his suspicion, he pens this letter to the owner of the shield:

“Enclosed is the report on your Comanche shield. I hope you find it as exciting as I do. I have been working on trying to gather together these remnants of George Catlin’s Indian collection for the last six or seven years … needless to say, I was ecstatic when I realized that your shield was a Catlin piece—another piece of the puzzle!…So far, it is the only known Catlin piece in private hands….Your shield had the good fortune to be in the hands of Charles Stephens whose record keeping was a museum person’s dream.”

But how exactly is Stephens a missing link to Catlin? It all begins with a generous society lady and her taxidermist.

Back in 1879, the main attraction at the National Museum of Washington (now the Smithsonian Institute) was a collection of Indian art and artifacts donated by the wife of wealthy Philadelphian Joseph Harrison, Jr.

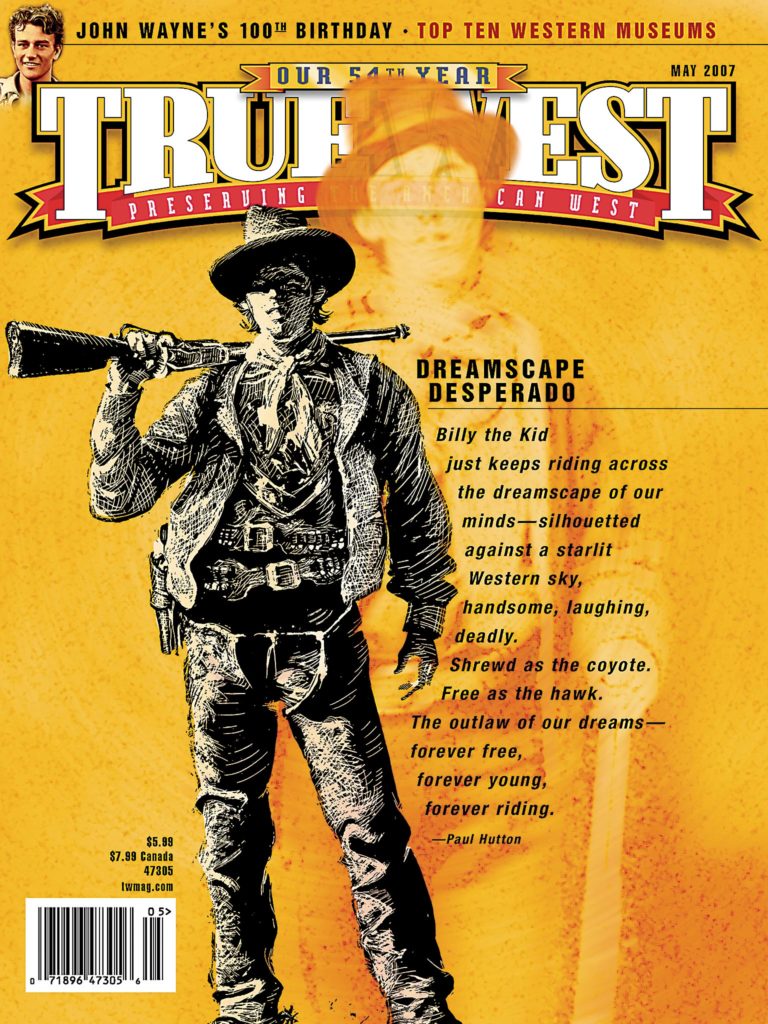

A gamble on a Texas colony had cost George Catlin his Indian gallery in 1852. Harrison acquired it in a sale organized to pay off Catlin’s debts. Strangely enough, those Indians were now resting in the city where Catlin’s mission first began. “Noble and dignified-looking Indians, from the wilds of the ‘Far West’” visiting Philadelphia in 1828 had inspired the lawyer to paint the portraits of future delegation Indians. He finally traveled to the West in 1830, mingling with natives until 1836. Then he began his earnest promotion of himself as historian of the Indian.

But he’d lose it all: more than 600 paintings and cultural artifacts. The story could have ended there. Except Mrs. Harrison didn’t donate all of the items to the museum. Some were given to the local taxidermist, John McIlwaine, who inspected the collection for her after Catlin died in 1872.

McIlwaine would pass away himself in 1885, and his collection was auctioned off. Thomas Donaldson, also of Philadelphia, purchased some of the items. After he died in 1898, his son sold off his collection, which is when Charles Stephens, of Philadelphia, purchased the shield. He carefully catalogued the item, including a rendered drawing of it on a card labeled “Shield—Catlin, Col., Donaldson Col.”

The Philadelphia Art Alliance exhibited Stephens’ collection after he passed away in 1932. Earl Horter must have spotted the shield there, as he purchased it from the Stephens family not too long after the show. In his notes, he described it as “Sioux shield of Buffalo hide—very old and finely painted—has seen much service—pendant to shield is a series of rawhide dec—to my belief one of the finest shields in existence—Stevens [sic] Col. of Phila.”

After her husband’s death in 1940, Mrs. Horter kept the shield. When she died in 1985, the shield went to Barry May of Dublin, Pennsylvania, and he sold it to the Morning Star Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico. At this point, Catlin was no longer connected to the shield, but Horter was still linked to it. It’s a stroke of luck that the shield ended up in William’s hands.

Not all collectors are as meticulous as Stephens. With an item passing down through many hands, its story may get lost in the interim (like this story almost did).

Collectors have saved these pieces of history over the years because of what they can teach us about our heritage. Even so, no collector will resist cracking a grin when an item ends up being more valuable than originally thought because of rediscovered provenance, or because a painting once worth $5,000 has a current market value of more than a million dollars.

If you find yourself inspired to Collect the West, take a note from the Stephens book of life. Keep clear records of every person you know of who has owned your prized collectible. It may not end up being a Catlin or a Schreyvogel, but you never know….