Have fun trailing the Lone Star outlaw from Texas to Kansas.

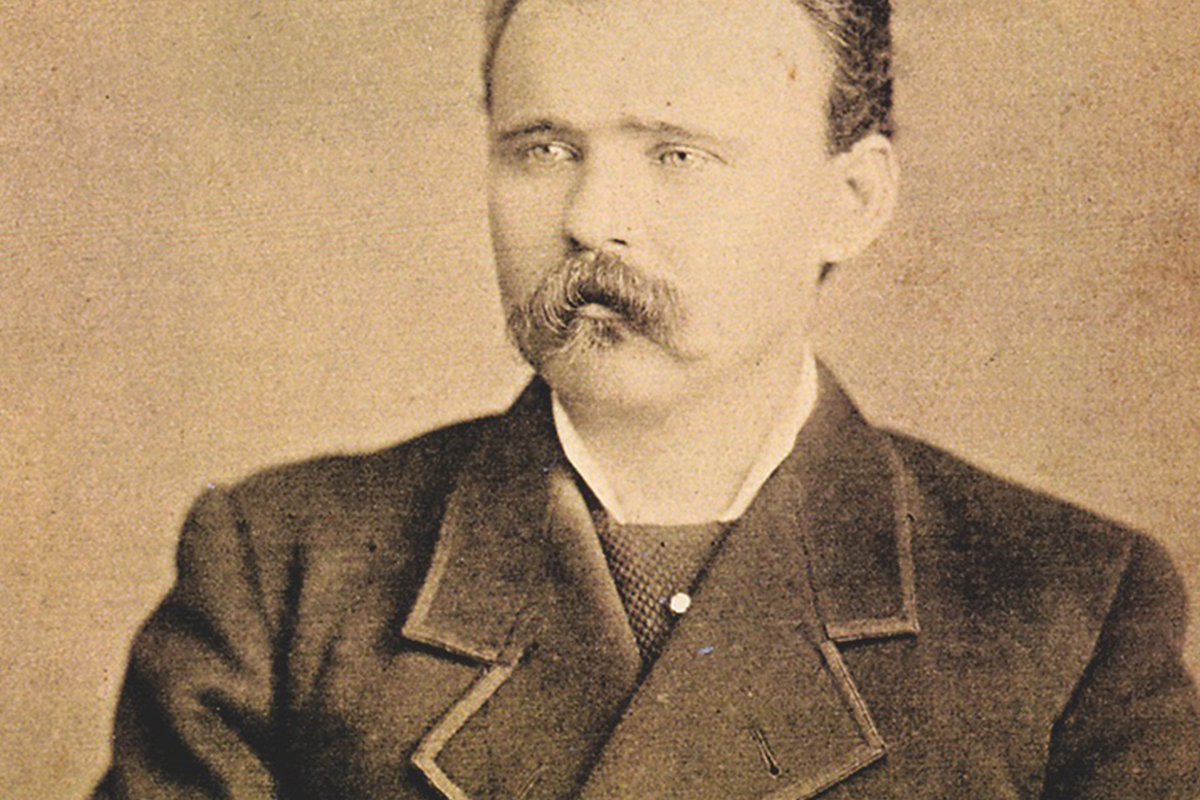

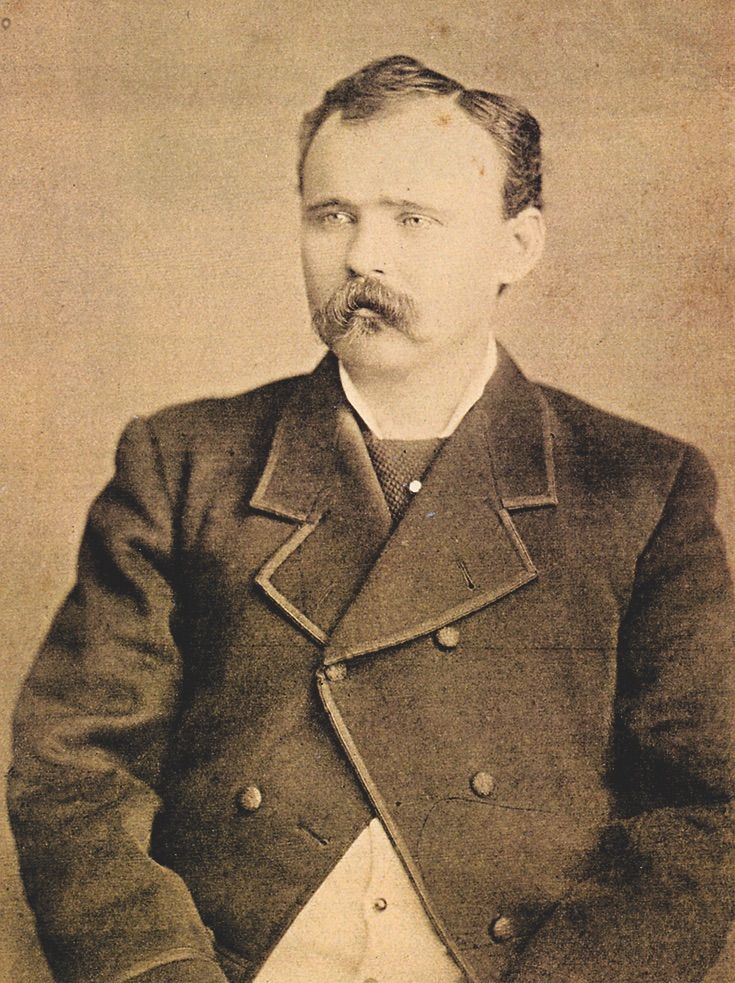

Charles E. Rankin, retired editor of the University of Oklahoma Press and astute historian of key figures of the Old West, posed a question a while back when we were having lunch and discussing James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok.

“What the hell was Phil Coe thinking?”

We agreed on the answer.

“He wasn’t.”

Coe’s decision to try to gun down Hickok on October 5, 1871, in Abilene, Kansas, might not have been the wisest choice for a 32-year-old, but it turned out to be a pretty good career move.

Coe was born in Gonzales, Texas (Gonzales Memorial Museum), in mid-July 1839. As far as we know, Coe didn’t spend time in the county jail, but his notable acquaintance, John Wesley Hardin, did—just not at what’s now the Gonzales County Jail Museum. That jail wasn’t built until 1887.

In 1862, Coe joined the Confederate army, becoming a lieutenant in the 2nd Texas Cavalry, but he was out of the army by the end of April 1863. If we judge by the acquaintances he had, he wasn’t keeping good company after the Civil War.

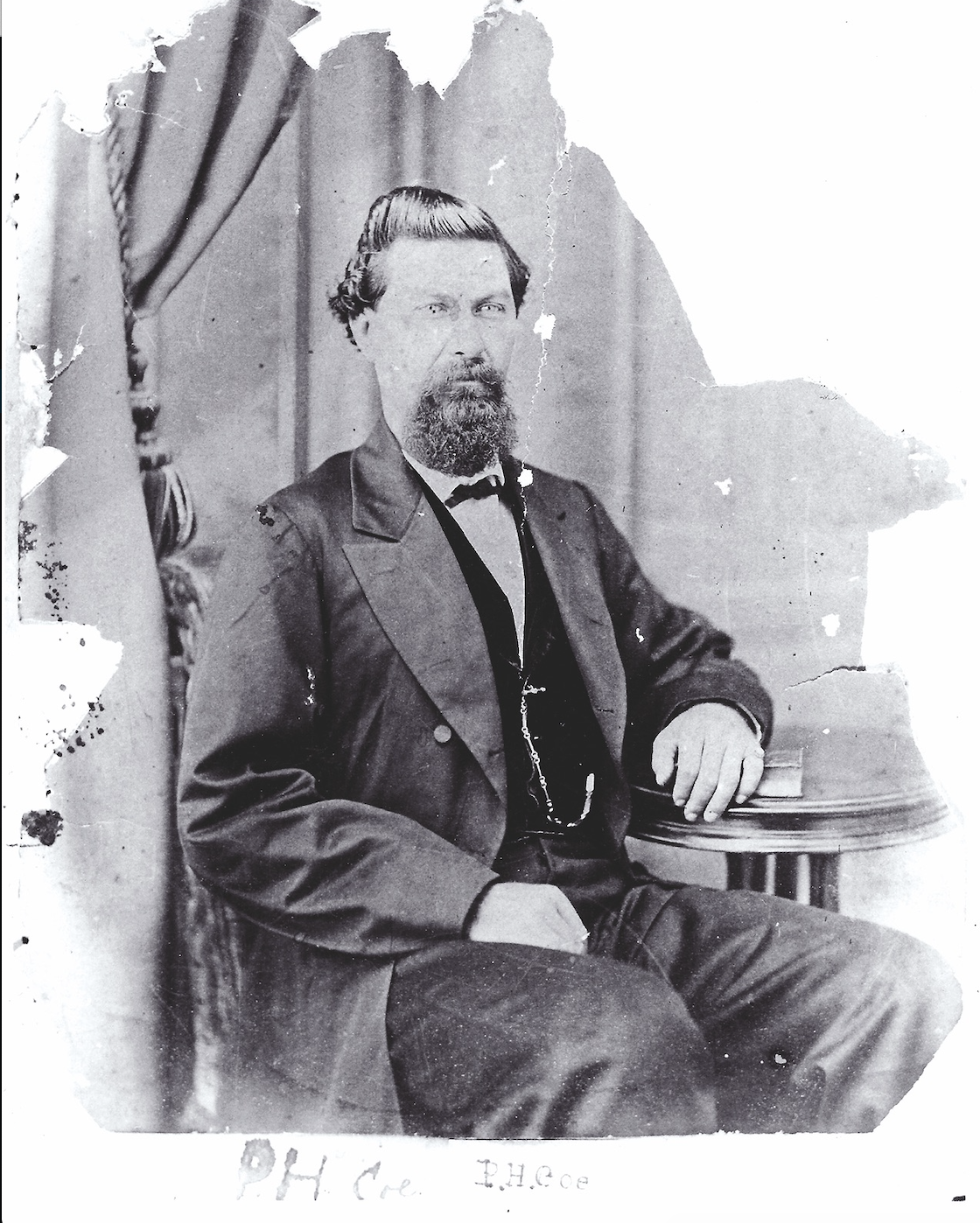

“I met Phil Coe first there in Brenham,” Hardin recalled in his autobiography, “that notorious Phil Coe.” Imagine how rowdy a person must have been to have John Wesley Hardin label him notorious. Coe also knew William Longley, a racist Texas gunman who would be hanged in Giddings, Texas, in 1878. And Coe served in the Confederate army and later partnered with gunman/gambler Ben Thompson. Thompson’s attorney—and his first biographer—William M. Walton gave this description of Coe: “six feet and some inches high, extensive of girth, commanding in appearance, Coe was a gambler by profession and a rough, overbearing jollier by habit.”

– Johnny D. Boggs –

Coe’s sister, Delilah, lived in Brenham with her family, which likely brought Coe to Brenham in 1869. Where he was before is hard to pinpoint, but some suggest that he, like many ex-Confederates, went to Mexico with Thompson to serve Emperor Maximilian. Since the Austrian archduke was executed by Juaristas in 1867, Coe would have been out of a job, and Brenham was, and still is (Brenham Heritage Museum, Brenham Fire Museum, Giddings Wilkin House Museum, Giddings Stone Mansion, Brazos Valley Brewing Company), a happening burg.

North to Kansas

By 1870, Coe had moved north, and is believed to have settled in Salina, Kansas, (Smoky Hill Museum, Central Kansas Flywheels’ Yesteryear Museum). How he got there isn’t known, but the best way to do it today is loosely following the Chisholm Trail through Waco (Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum), Fort Worth (Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame, Stockyards Museum) and north through Oklahoma past Duncan (Chisholm Trail Heritage Center), Oklahoma City (National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum) and into Kansas: Wichita (Old Cowtown Museum) and Newton (Harvey County Historical Museum).

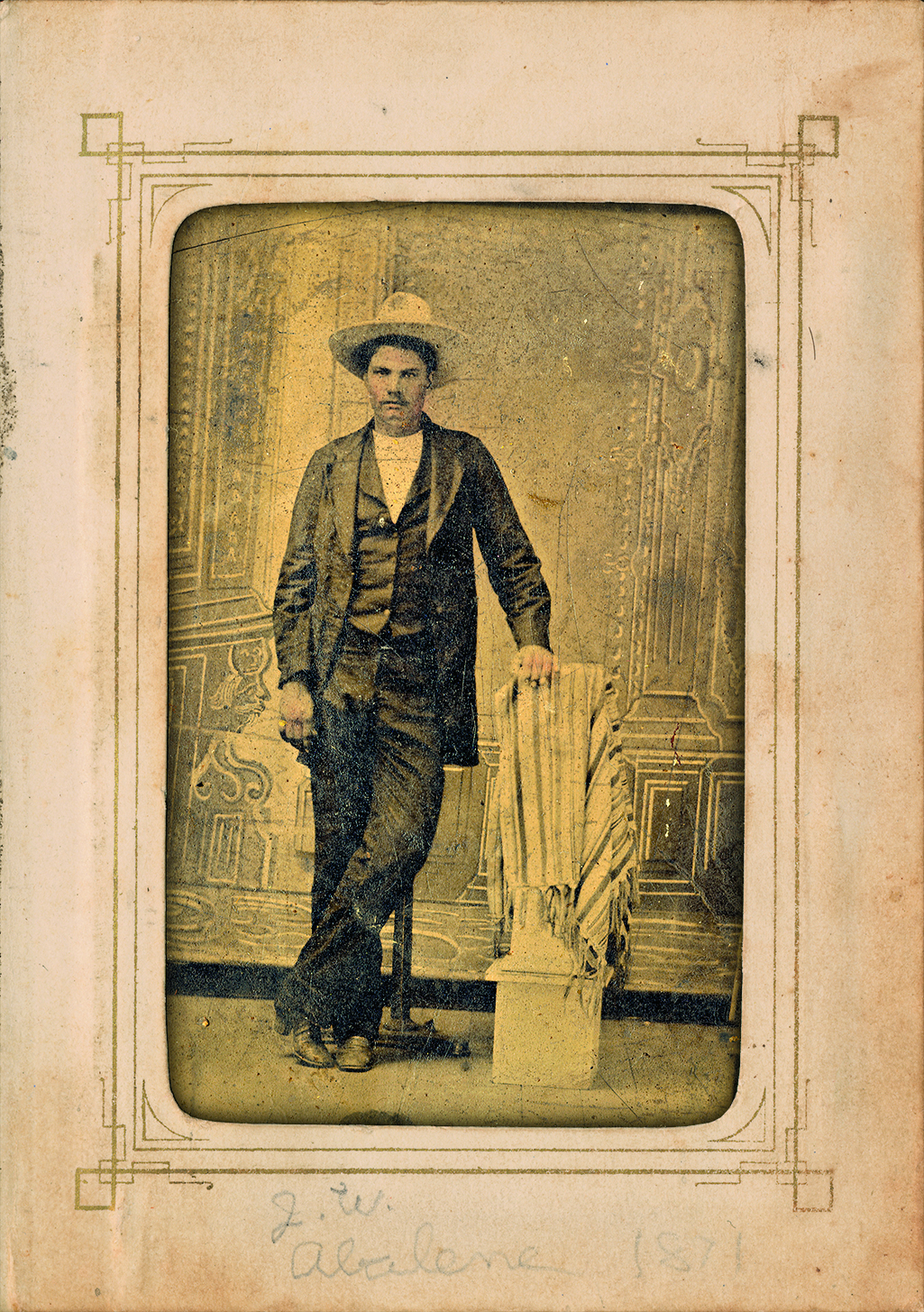

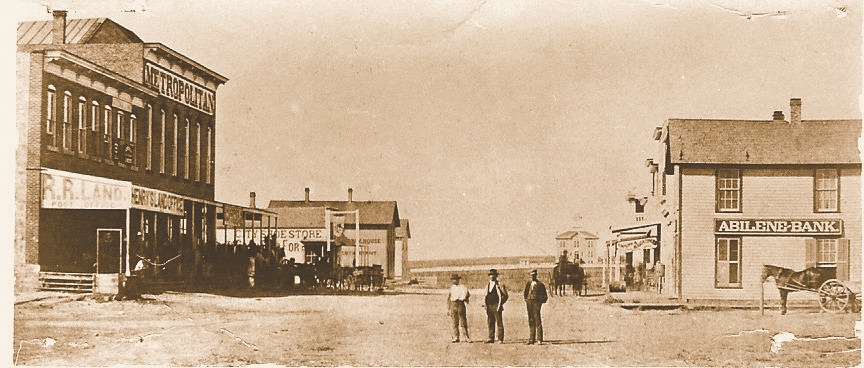

In May 1871, Coe was in Abilene, Kansas. Who could blame a Texas gambler for heading east from Salina to that rip-roaring cowtown?

“I have seen many fast towns,” Hardin recalled, “but I think Abilene beat them all. The town was filled with sporting men and women, gamblers, cowboys, desperadoes and the like. It was well supplied with bar rooms, hotels, barber shops and gambling houses, and everything was open.”

Abilene (Dickinson County Heritage Center, Old Town Abilene, Seelye Mansion, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum) had grown substantially since the first Texas longhorns arrived in 1867, and Coe and pal Thompson weren’t the only ones drawn there in 1871, Abilene’s last season as a trail town. Hickok was appointed city marshal.

Coe and Thompson ran the Bull’s Head Saloon. Coe and Thompson were Texans; Hickok, a Yankee. They just didn’t get along.

– Johnny D. Boggs –

One commonly mentioned reason for the Coe-Hickok animosity involved a woman, Jessie Hasel (or Hazell), usually identified as a prostitute or madam. As Tom Clavin, author of Wild Bill: The True Story of the American Frontier’s First Gunfighter, points out: “There could be 50 or more men to every woman, and ‘love triangles’ were unavoidable.”

Hickok might have been able to take such things in stride, but Coe was hot-tempered. Of course, one problem with that theory is no record of Jessie Hasel/Hazell has ever been located. Another account says that Hickok forced Coe to play faro honestly.

But my favorite reason is this: Ever the advertising executive, Coe had a bull painted on his Texas Street saloon. The artist captured said animal in anatomically correct fashion. Hickok wasn’t a prude, but in the Victorian Age, he strenuously objected to such vulgarity. He demanded that the atrocity be painted over, or he’d burn down Coe’s saloon. Hickok, legend has it, got his way and paint was used to castrate the offending bull.

If we believe Hardin, Thompson asked Hardin to kill Hickok, but Hardin, no idiot, declined and eventually left Abilene. So did Thompson, to join his pregnant wife in Texas. Coe stuck out the cattle-trail season through the fall and took in the Dickinson County fair, where merriment was had by all.

– Courtesy Chisholm Trail Heritage Center –

Filled with good spirits and plenty of ardent spirits, several Texans went through town, demanding that citizens buy them drinks. By some accounts, they even approached Hickok, who obliged the revelers. But in front of the Alamo Saloon, Coe fired his revolver, and Hickok raced to meet the Texans, demanding to know who ignored the Abilene law that prohibited the carrying of firearms in the city proper, let alone shooting one.

The record says Hickok was outnumbered roughly 50-to-1.

Coe said he had fired at a stray dog, and then he fired at Hickok.

Coe missed. Hickok didn’t, and the Texan, hit twice in the abdomen, died four days later. Mike Williams ran to help Hickok, who shot and killed his deputy by accident. Wild Bill grieved, then got mad, and ran gamblers and cowboys out of town.

Coe’s body was returned to Brenham, where he was buried at Prairie Lea Cemetery.

Coe was “a gambler,” the Abilene Chronicle reported, “but a man of natural good impulses in his better moments” but also “had a spite at Wild Bill and had threatened to kill him.”

Clavin put it another way. “Coe could not have been in his right mind when he decided to take on Wild Bill single-handedly.”

Maybe not, but would anyone remember Phil Coe today if he had been thinking like a sane man?

A Wide Spot in the Road

SID RICHARDSON MUSEUM

– Johnny D. Boggs –

Fort Worth, Texas, has grown a lot since its Wild West days, but it has never forgotten its cowtown roots. And one of the best places for art lovers and Western history lovers to be transported to the Old West is downtown’s Sid Richardson Museum. Sid Richardson, an oilman and philanthropist, started collecting works by Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell in 1942, but he also liked Charles Schreyvogel, Frank Tenney Johnson and Edwin W. Deming, among others. Richardson died in 1959, but his collection lives on in Fort Worth’s historic Sundance Square. Admission is free, and the museum is a must stop for anyone touring downtown. But even when COVID restrictions keep the front door closed, the museum is offering virtual tours. You don’t even have to take a road trip to Cowtown to see get a glimpse of history and art. SidRichardsonMuseum.org.

Good Eats and Sleeps

Good Grub: Reba’s Pizzeria & Deli, Giddings, TX; Volare, Brenham, TX; Tim’s Place, Duncan, OK; The Cozy Inn, Salina, KS; Hitching Post Restaurant, Abilene, KS

Good Lodging: Belle Oakes Inn, Gonzales, TX; Ant Street Inn, Brenham, TX; Flying W Guest Ranch, Sayre, OK; C&W Ranch Bed & Breakfast, Smolan, KS; Abilene’s Victorian Inn Bed & Breakfast, Abilene, KS