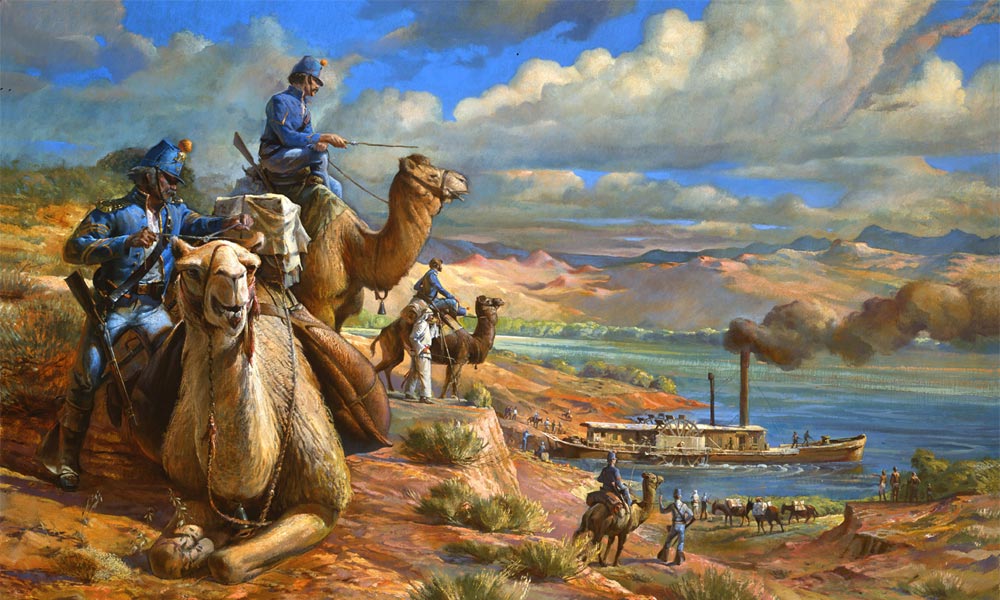

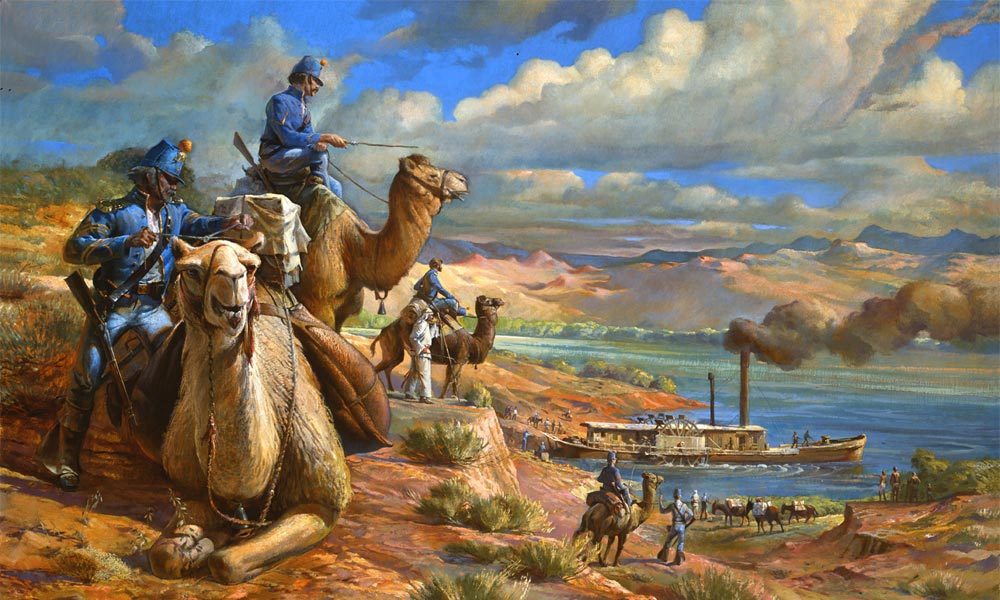

One of the West’s most bizarre events took place along the Colorado River on a grey January morning in 1858. A camel caravan looking like something right out of the Arabian Nights was preparing to cross the muddy river. Riding wagon painted bright red like some circus ringmaster sat a dashing Army lieutenant named Ned Beale. He was leading the Camel Corps, surveying a wagon road to California that would one day be the storied Mother Road, Route 66.

The group of camels plodding across the Arizona was indeed a peculiar sight. Their strange mannerisms and homely looks were a great curiosity to the local natives but prompted mules and horses to stampede.

This unfamiliar event was followed by something just as outlandish in the Mohave Desert. A tiny boat belching steam was churning its way upstream, its noisy, wood burning engine hurling billowing clouds of black smoke skywards.

Although this chance meeting in the middle of nowhere was accidental, both were part of a grand plan by the U.S. Government to establish passageways through and across the vast terra incognita that was now a part of the United States. Both are relatively unknown chapters in the illustrious history of the West.

The United States had just acquired 529,000 square miles of virtually unexplored and unmapped land as a result of the recent war with Mexico; land that included all or parts of today’s Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming and Colorado.

About that same time gold was discovered in California and thousands of American emigrants were heading West. They were going to need roads to get there. The storied Army Corps of Topographical Engineers were charged with surveying these transcontinental roads from the Canadian border to the Mexican. Future transcontinental railroads would follow these same surveys. And nearly a century later, Interstate highways.

Before the coming of the railroads the task of transporting goods across the great southwestern deserts was never an easy one. The terrain was rough enough to tear up the feet of horses and mules. Water was always scarce and suitable forage for the animals made it necessary to carry the feed on pack animals, taking up valuable space. A beast of burden was needed that could pack a heavy load, live off the natural forage along the way and could travel a long distance without a drink of water.

Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis wanted to test the feasibility of using camels as beasts of burden across the waterless land. The Great Camel Experiment would be unique in the annals of western exploration.

The first American to come up with the idea of using camels was 2nd Lt. George Crossman during the Seminole Wars of the 1830s. He pitched the idea to Major Henry Wayne who in turn pitched to Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis. When Davis became Secretary of War 1853-1857, he pitched it to President Franklin Pierce for an appropriation. After Congress appropriated thirty thousand dollars Major Wayne, accompanied Lt. David Porter set out on the USS Supply to the Middle East to purchase some camels.

On February 15th, 1856 the ship embarked for America with 33 camels on board. On the way one died and two were born so they arrived on May 14th with a net gain of one camel. A year later another shipload arrived increasing the total by forty-one.

The man chosen to lead the survey of the 35th Parallel was the irrepressible Lt. Edward Fitzgerald “Ned” Beale. Beale, a graduate of the Naval Academy, is undoubtedly one of the unsung heroes of the American West. His life story reads like something out of dime novel. In December, 1846, he was with General Stephen Watts Kearny’s Army of the West when it was pinned down and under siege at San Pasquel, near San Diego, during the Conquest of California. Beale, Kit Carson and a Delaware Indian sneaked through enemy lines and traveled on foot to San Diego for reinforcements to rescue the trapped American force. Following the discovery of gold in California he was chosen to carry the news to President Millard Filmore. Disguised as a Mexican he made an epic dash through Mexico, outriding his pursuers and shooting his way out of several scrapes. He delivered a pouch of gold nuggets to the White House proving the gold discovery was not a hoax and triggering the California Gold Rush.

The arrival of camels in the American Southwest failed to bring a chorus of cheers from the packers and muleskinners. They should have been welcomed as they could carry 800 pounds, live off the local forage, and go for long periods without water. Besides that they could travel anywhere from 35 to 75 miles in a day. Alas, the homely beasts were extremely stubborn, had terrible breath and were known to be extremely temperamental. Couple that with a spirit of intractable independence and were difficult to manage. One explanation for all that was the female camels came in heat only once a year and the males were always in heat.

The muleskinners hated them, packers and teamsters cursed them unmercifully while horses and mules shied when they plodded by. The language barrier presented no small problem. The Americans couldn’t speak Arabic and the camels wouldn’t learn English. Following the old adage “it takes a camel driver to drive a camel,” the government had the foresight to import camel drivers. They were a colorful bunch with names like Long Tom, Short Tom and Greek George. These weren’t their given names but had to do as the Americans couldn’t pronounce their Arabic names anyway. The most famous of these was Hadji Ali and since that one didn’t roll off the tongues of the Americans his name was corrupted into Hi Jolly.

His original name was Philip Tedro and he was born in Greece around 1828, of Greek and Syrian parentage. At the age of twenty-five he converted to Islam and took the name Hadji Ali. He reverted back to Philip Tedro in later life.

By the middle of August, 1857 the camel brigade was on its way. Accompanied by the Middle Eastern “camel conductors” in their traditional garb, the caravan made a colorful spectacle as it passed through villages along the way. Lt. Beale looked and played the part of a circus ringmaster, riding in a wagon painted bright red. The camels were packing 700 pounds, twice what the mules could carry. Beale usually rode a mule but once for a social call on a military post he climbed on a white camel named Seid. No doubt the appearance of a military officer sitting high on a white camel had the desired effect.

Beale couldn’t have been more pleased with his camels. They endured the arid lands between Albuquerque and the Colorado River especially well. During a stretch of thirty-six hours without water the horses and mules suffered but the camels didn’t falter.

The powerful Mule lobby in Missouri was the most vocal opponent of the Camel experiment. They threw a hissy. In reality they didn’t like the competition. However, Lt. Ned Beale, the officer who implemented the camel survey championed their attributes calling them “lovable and docile.”

He had a hard time convincing others, especially when whole pack trains were known to stampede at the mere sight of the camels.

The beasts passed the supreme test when Beale was challenged to pit his camels against packers’ mules on a 60-mile endurance race. Using six camels against twelve mules, a 2.5 ton load was divided among the camels and two Army wagons, each drawn by six mules. The camels finished the race in two and a half days while the mules took four.

On October 17th, 1857 the camels arrived at the Colorado River and encountered a military steamboat. This had to be one of the most unusual occurrences in the annals of the American West.

With Hi Jolly singing to encourage his camels to swim the swift currant of the river they successfully crossed with no losses. Two horses and ten mules were lost on the crossing. The camel caravan reached Fort Tejon, California in November still carrying their loads of 600 to 800 pounds. Their historic mission was accomplished.

The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 ended any hope for the building of a railroad along the 35th Parallel in the near future. The government had no more use for its camels and they were either sold as military surplus or turned loose to roam the western deserts of Arizona and California.

The Army’s experiment with camels was short-lived, but Hadji remained in the Southwest and for the next 40 years would divide his time between delivery of the United States mail, hauling freight (over roads he had helped to explore and establish), prospecting, and serving the United States cavalry as a scout and mule packer.

He met and married Gertrudis Serna in Tucson and they married in married 1880. They had two daughters but he continued to drift and finally took up residence around Tyson’s Well. The two remained estranged until his death in 1902 on the road between Wickenburg and the Colorado. He’d gone out looking for a stray camel. Later some cowboys working cattle came upon his body, his arms wrapped around the neck of the camel. Both had perished in a sand storm. The name Philip, means “lover of horses” but Philip Tedro in reality was a camel whisperer.

The last camel from the original group died at the age of 80 in 1934 at a zoo in Los Angeles. The average life of a camel is fifty so the climate of the Arizona desert must have suited him. The last camel, a descendant of the original herd was captured in the wilds of Arizona in 1946. The last reported sighting of a wild camel in North America was in Baja California in 1956.

When the rails did cross Arizona in 1883 they closely followed survey Beale and his camels made nearly a quarter century earlier. In 1912 the wagon road became part of the National Trails Highway aka the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

On November 11th, 1926 federal highway officials put the finishing touches on the new 2,400-mile interstate between the Chicago and Los Angeles and named it Route 66. But that’s a story for another time.