Many nights, during the late 1970s, Ralph McCalmont had to remind himself he was trying to save Oklahoma’s “magic city.”

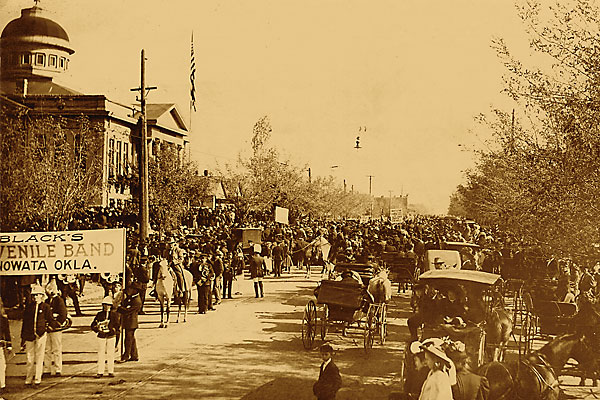

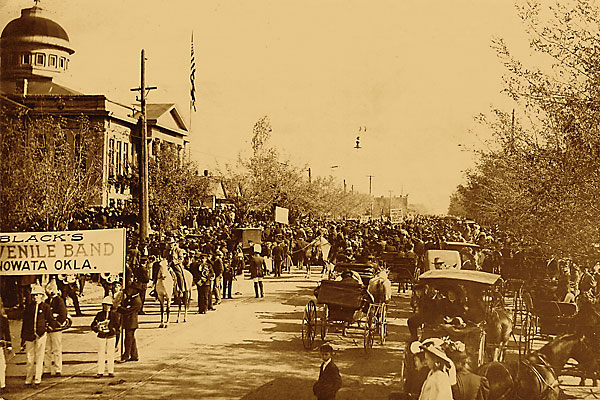

Opposition was so loud and so hurtful, he wondered if it was worth it. Then he thought of Guthrie—a city created in just six hours, going from zero to 10,000 residents on April 22, 1889, in President Benjamin Harrison’s “Hoss Race” that opened up two million acres of Indian Territory for land claims.

McCalmont wasn’t alone in trying to save this Oklahoma boomtown. Bill Lehmann, too, kept in mind how special this territorial capital was and how it had been the first state capital when Oklahoma got the treasured nod from Congress in 1907 (and its Statehood Centennial gala last year was perhaps the most organized and celebrated of any state).

Neither man had any trouble seeing the “Rip Van Winkle” stage of Guthrie’s life: the city had been “asleep” for 70 years after Oklahoma City stole away the state capital in 1910.

Both men—Ralph, a banker, and Bill, a newspaper publisher—couldn’t even look around Guthrie in the 1970s and see its old glory because its antique brick buildings had been covered in aluminum slip covers. Yet neither man could turn his back on what Guthrie had been.

“It was so awful,” says McCalmont, and you can still hear the pain in his voice all these years later. “We were so unpopular; they wanted to burn me in effigy.”

Those who opposed change—who thought Guthrie was just fine as a “nice, sleepy little town”—didn’t dissuade the men as they worked side by side with about a dozen others to bring about a transformation.

Today, Guthrie is the nation’s largest historic district—1,800 acres of it. The city council recently passed a strict zoning law that assures its historic downtown will never again slip.

You can’t find anyone who doesn’t want to brag about Guthrie these days—including those who made life so miserable for the few men and women fighting to bring back the “magic city.”

As its chamber of commerce brags, “Guthrie had been constructed for perpetuity in a manner befitting a capital city. Today, through careful restoration, a rich architectural legacy has been preserved in all its grandeur. Guthrie’s magic has returned!”

You can just see the secret smile on the faces of the men who made this happen when they think back on their efforts.

Taking the First Steps

Lehmann, who published the Guthrie Daily Leader, started things off in the 1960s, when he saw Guthrie’s citizens were ignoring its history. “We were about the only city in Oklahoma that didn’t have some kind of museum,” he remembers.

The city was asking voters to approve seven new bonds for city improvements, including one for a new library. Lehmann went to the council and told them if they’d turn the old Andrew Carnegie Library into a museum, his newspaper would support all the bonds. That old-fashioned horse trading is how Guthrie got its first museum. “And because I had suggested it, they made me chair of the study committee,” he says.

Lehmann turned to high school history teacher Don Odom for help, and Odom got his students involved. Guthrie’s first museum opened.

Lehmann repeated his act a decade later, raising private financing to buy the old State Capital Publishing Co. to turn it into a newspaper museum. “Everything was still there,” Lehmann remembers. “It was like the printers had taken off their aprons and gone home for the night.”

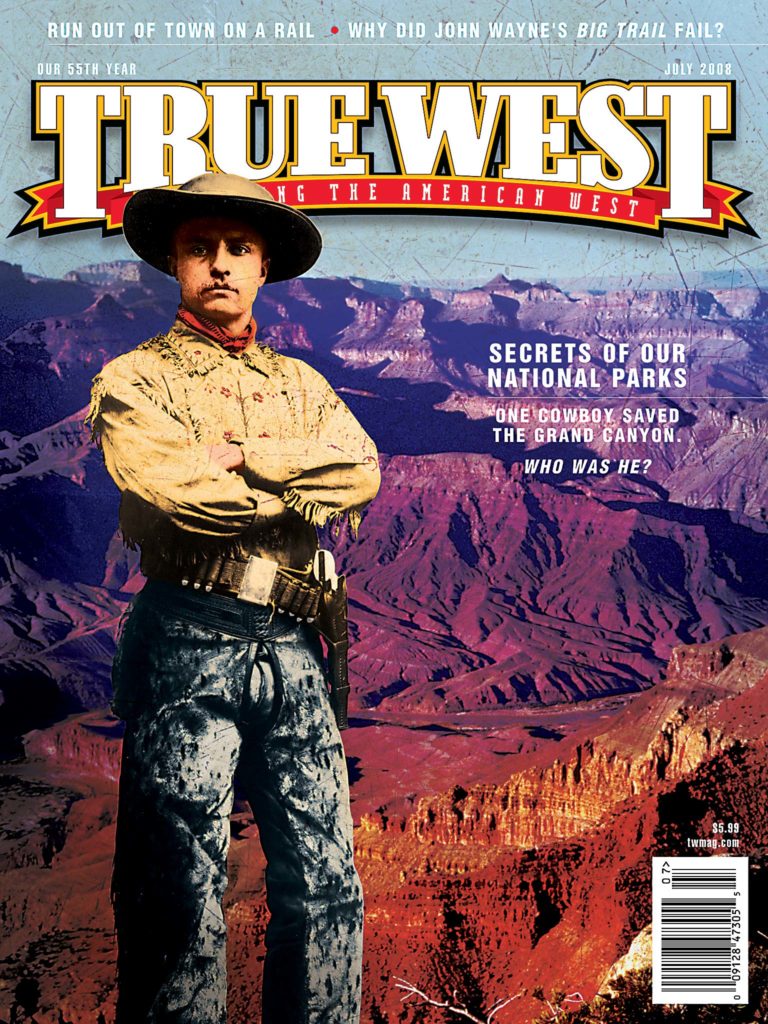

By then, Lehmann had help from new resident Ralph McCalmont, who came to town to run the First National Bank of Guthrie. “Bill roped me into the projects,” McCalmont remembers. “Bill wrote a historical column, and my bank advertised in his paper. I sent some of the columns to my uncle, and he wrote back and said, ‘This town is worth saving.’” His uncle happened to be Joe Small, the founder of True West magazine. “He was my encourager,” McCalmont says.

“This was my first attempt at historic preservation, and I found it is never easy,” he says. “I started out thinking of it as economic development, but the more I got into the story of Guthrie, I saw what it really was.”

McCalmont remembers flying a small group from the town in his private plane to other small communities to see what those citizens had done to save their towns. “We didn’t have what some other towns did, like mountains and skiing; the only thing we had was what had been there before,” he says.

Originally, they focused on saving a “couple blocks of downtown,” hoping that sprucing them up would bring in new businesses. The group sought economic development grants from Washington and were turned down flat. “The town had no city planning, the chamber wasn’t interested and we put together the grants in the basement of the bank,” McCalmont says.

While in Washington, fruitlessly lobbying for that first grant, someone suggested they check with the National Trust for Historic Places. They were rejected there too. (McCalmont says someone from Oklahoma City was on the national board and wasn’t anxious for competition from Guthrie.)

Yet the editor of the National Trust’s newspaper, Wendy Adler, found their story intriguing. Lehmann had penned an article so compelling, she printed it in the Trust’s next issue.

Thanks to such prestigious coverage, Guthrie’s legislator Don Coffin called McCalmont to say they had to try again. A weary McCalmont wasn’t up to writing yet another grant, but he dusted off one of the earlier ones he’d stored in a shoe box in his office. Guthrie got its first $1.1 million grant for historic preservation.

That took place in 1979. Over the next five years, Guthrie received “grant after grant”—some $4 million worth, all leveraged with private funds to stretch the dollars three or four times

Guthrie Today

With the aluminum siding stripped off and empty two-story brick buildings brought back to life, lots of people want to experience this “magic city”—and spend their money. McCalmont notes that “economic viability is crucial” to the success of preservation.

“Now Guthrie is one of the dozen most distinctive destinations in the country,” McCalmont brags. “And we have more bed and breakfasts than any other city, than Seattle. It’s wonderful now.”

Lehmann is “delighted” at how it all turned out, and he likes how much life has come to his town. “We have several festivals during the year that are very popular,” he says. Those include a Victorian Christmas celebration that lights up the old town, an “Apples and Quilts” festival in the fall, an International Bluegrass festival in October and an 89’ers celebration in the spring to commemorate Harrison’s Hoss Race.

Although Lehmann and McCalmont can still remember the pain their first efforts brought them, they think it was all worth it. As McCalmont puts it, “We learned a small group of people, if they have a just cause, will prevail.”