Being born on the same day as George Custer, I have known about him practically all my life. My great-grandfather McDermott, who was born in 1870, remembered hearing about the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn, which made that history much closer.

My great-great-grandfather was John Bartholomew, a hero in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe. Wounded early in the fight, he continued to lead troops under his control to the end.

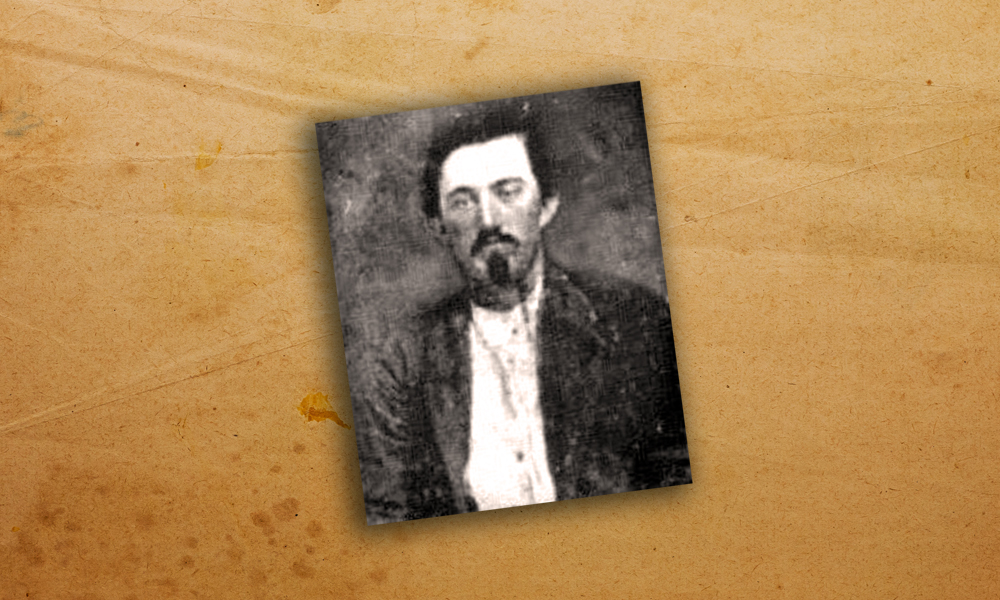

Red Cloud earned his notoriety as the only American Indian leader who defeated the U.S. Army in a war. He attracted enough followers on the Northern Plains to effectively deal with U.S. troops. The treaty that ended the conflict, however, had provisos that made future white expansion and settlement possible.

What most people don’t know about Red Cloud is that he schemed to have Crazy Horse killed in 1877.

Red Cloud’s early childhood illuminates his resolve. At nine, he hunted buffalo. When his arrows did not penetrate one of his targets more than a few inches, he dashed up to the huge animal and tried to push them in.

Red Cloud was photographed more than any other Indian of his century because the images publicized his power.

Red Cloud didn’t speak English, but he understood it. One might surmise that he chose to speak only Lakota because his language was equal importance to that of the whites.

If I could ask Red Cloud anything, it would be why he and other chiefs and headmen did not mention that the Black Hills were sacred to the Sioux in discussions concerning the sale of the same in 1875-1876.

Some Lakotas today hold a black mark against Red Cloud because he was one of those who agreed to sell the Black Hills.

“What is good for the white is good for the red, and he has no more right to stand over us in civil life with a gun than he had to crack his whip over the back of a slave.” Here, Red Cloud identified the great hypocrisy of the 19th century: U.S. troops fought to free slaves on the one hand and incarcerate Indians on the other.

One of my favorite research discoveries was finding the Mountain District Records (Bozeman Trail forts) in the National Archives after Dee Brown and Robert Murray wrote the records had been destroyed in a fire. I also found the Fort Phil Kearny post surgeon’s body analysis that determined William Fetterman had not committed suicide in 1866, but died from a blow to head with a club.

What few people know about me is that I once had charge of 1,000,000 złotys to finance a trip of 30 American historians, preservationists and architects for a 30-day exchange program with counterparts in Poland.

I collect copies of documents. I have 12 four-drawer cabinets full of materials covering the Indian Wars in the West from 1849-1890.

My next book will be about life in the frontier army, a series of essays on subjects such as, “Was George Armstrong Custer Right About James Fenimore Cooper and What Did Chingachgook Think?”

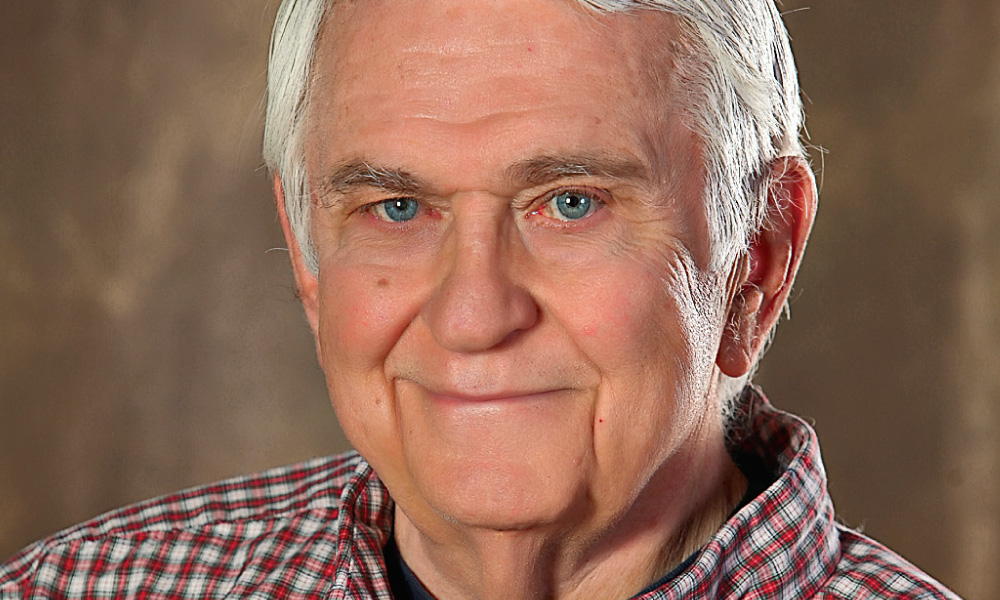

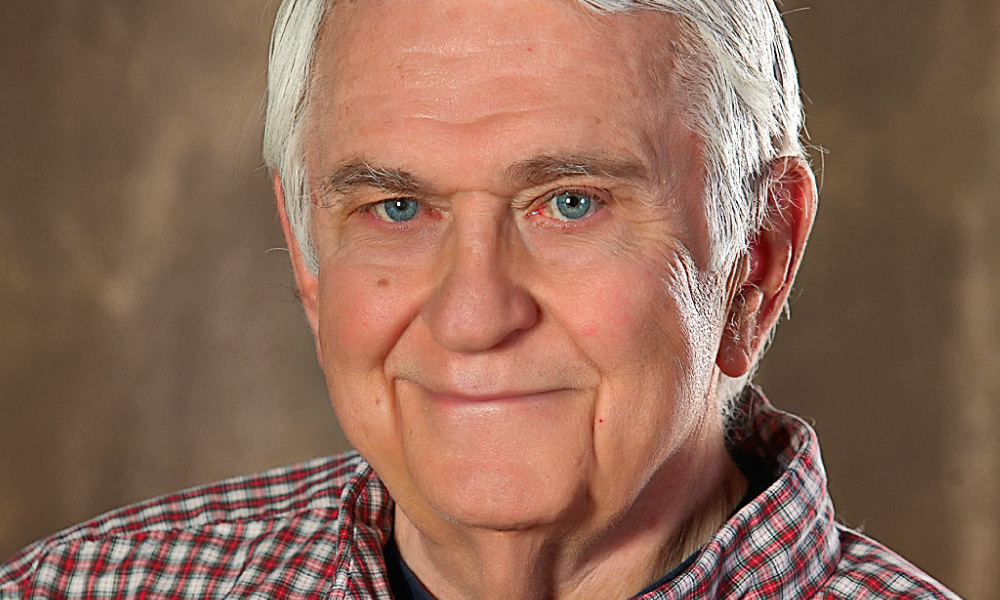

John D. McDermott, Author

John D. McDermott is the author of 15 books on Indian-military relations in the American West. His latest book, published by South Dakota Historical Society Press, is Red Cloud: Oglala Legend. Residing in Rapid City, South Dakota, he served as a historian for the National Park Service and as policy director for the President’s Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, writing many procedures that guide today’s national preservation efforts.