A Vision Realized on the 145th Anniversary of the Battle

The Indian Memorial at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in Montana was created to honor and recognize those American Indians who died to preserve their traditional way of life at the 1876 battle, as well as to provide a better understanding of the causes and consequences of what is popularly known as “Custer’s Last Stand.”

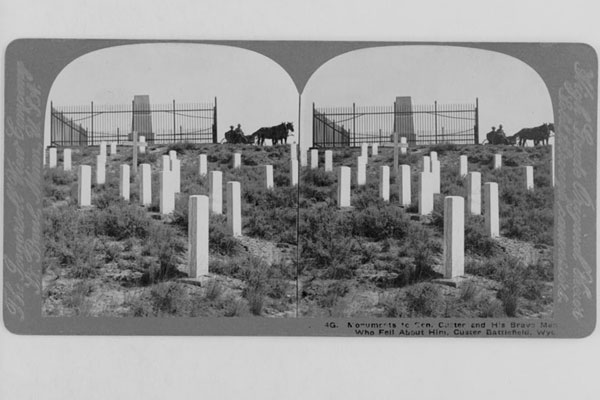

The long-delayed effort to provide a balanced interpretation of this historic clash represents a notable departure from the previous focus of the National Park Service (NPS) on Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and the U.S. Army’s side of the story. Since the battlefield’s inception as a national cemetery in 1879, retired NPS historian Jerome A. Greene notes, the U.S. government had “viewed the Indians largely as faceless people without historical investment in the struggle that had occurred there, even though the short-term aftermath had proved cataclysmic to their traditional existence.” Thus, a major reassessment of the historical treatment of Native Americans at the battlefield was long overdue.

Congress mandated the memorial in the 1991 legislation that changed the name of Custer Battlefield National Monument, emphasizing that there was no commemoration of those Native Americans “who gave their lives defending their families and traditional lifestyle.” Public Law 102-201 also required that it be located “in the vicinity of the 7th U.S. Cavalry Monument.” It did not, however, provide public funding.

The Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt approved both the memorial’s design and its site near “Last Stand Hill” in 1997, based on the recommendation of an 11-member Advisory Committee established by this legislation. The committee included nine representatives from the tribal groups that had participated on both sides of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The selection was the result of a national design competition that involved over 500 applicants, whose names were withheld from the committee. Philadelphia residents John Collins and Allison Towers submitted the winning design, which encompassed an earthen circular form, metal sculptures of mounted warriors and a “Spirit Gate” facing the cavalry monument.

All Images by C. Lee Noyes Unless Otherwise Noted

Once the memorial design and its projected costs were known, the most difficult challenge was how to pay for this tribute, in view of the failure to receive sufficient donations from business and other private sources. “The memorial,” former Little Bighorn Battlefield Superintendent Neil Mangum noted, “was clearly not going to be done with the private sector. We were not going anywhere with fundraising.” Nor did raising park entrance fees accomplish this goal. Finally, Congress appropriated $2.3 million in 2001 to fund the memorial, due largely to the efforts of Mangum and other NPS officials who advised Montana’s congressional delegation. “It took ten years,” the superintendent noted, “but finally there will be an Indian Memorial at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.” Besides his role in raising the money, he deserves much of the credit for fostering the balanced historical interpretation at the park that the memorial so clearly reflects.

Dedication of the me-morial on June 25, 2003, highlighted observance of the 127th anniversary of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Private tribal ceremonies before the formal ceremony offered prayers for peace that emphasized the sacred nature of the observance. The presence of several veterans groups testified to the event’s importance to those who had served their country, as the Fort Peck Sioux Tribe Post 54 and Fort Hood 7th Cavalry color guards led the procession to the memorial. The official program at the park’s Visitor Center amphitheater included remarks by representatives of the five tribes who fought on both sides at the battle.

Opening remarks by Crow tribal chairman Carl Venne set the tone for the event attended by an estimated four thousand persons. “It is now time,” he declared, “for the U.S. government to recognize Indians as true Americans because I am proud to be an American.” His welcoming visitors to “Crow Country” underscored the fact that the 1876 battle had occurred on the tribe’s reservation and that six Crow scouts had fought on the side of the soldiers. The chairman urged the audience to acknowledge the event’s theme, “Peace Through Unity,” expressed by tribal elders Austin Two Moons of the Northern Cheyenne and Enos Poor Bear, Sr. of the Oglala Lakota. Others echoed this appeal for reconciliation.

Montana Governor Judy Martz, U.S. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell and Secretary of the Interior Gale Norton were among the dignitaries attending the ceremonies. As President Bush’s representative, Secretary Norton observed that the memorial represented “another step” in the vision of the Lakota Black Elk toward peace between nations. “Children will come to this battlefield,” she noted, “and [now] understand the tragic clash of cultures.” The program also includ-ed an unscheduled but rumored appearance by actor and activist Russell Means of the American Indian Movement.

Ceremonies also in-cluded the dedication of markers for two warriors killed at Custer’s battlefield and the Reno-Benteen defense site.

The Indian Memorial “is in the correct place at the correct time,” historian Greene has written. “The dedication of the memorial to their fallen held great significance to the people of the tribes involved in the battle of the Little Bighorn.…The people’s ownership of the place was acknowledged and their dignity respecting it affirmed.”

Visitors to Little Bighorn Battlefield will not only appreciate the magnitude of the landscape on which the 1876 battle was fought but also the American Indian perspective of this historic clash of cultures. Historians will continue to argue about the battle’s details, its legacy and the reasons for Custer’s defeat (or the Indians’ victory). Nevertheless, by exemplifying the commitment to provide true interpretive balance, the Indian Memorial clearly illustrates the fact that there are at least two sides to the story of the Little Bighorn.

(l.-r.): U.S. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell, Former Little Bighorn Battlefield Superintendent Neil C. Mangum, Interior Secretary Gale Norton, Montana Governor Judy Martz and Crow Tribe Chairman Carl Venne.

POSTSCRIPT

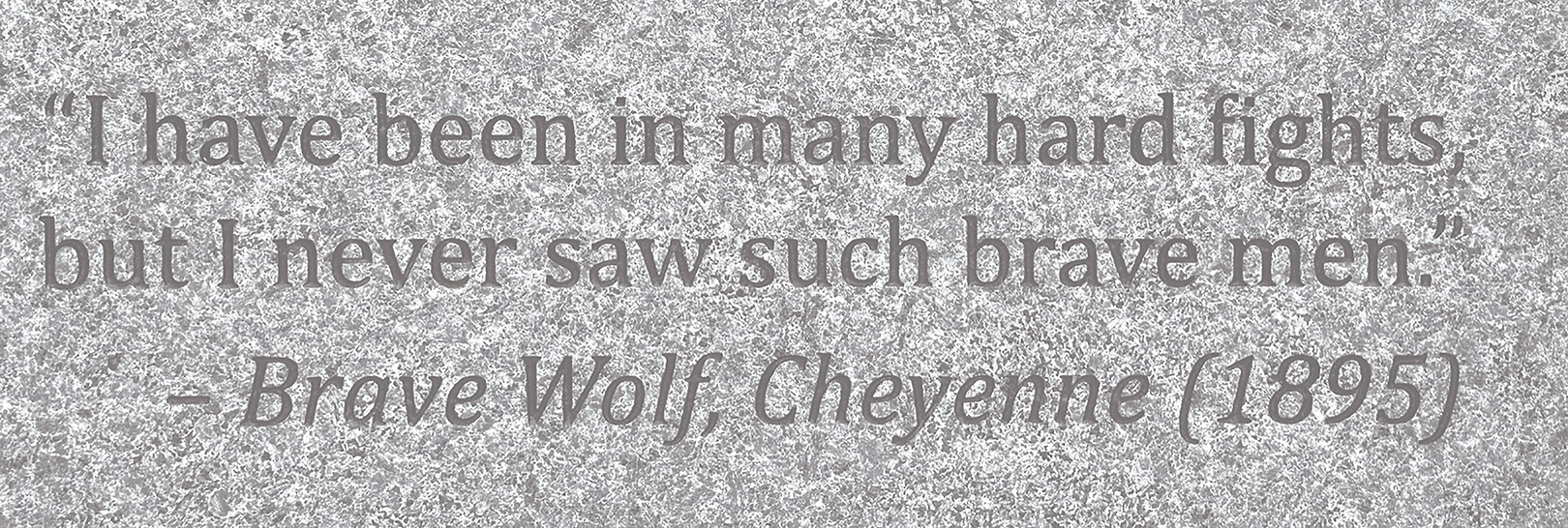

On June 25, 2014, the NPS rededicated the Indian Memorial to commemorate installation of permanent interpretive panels that pay tribute to all Native people who fought at the 1876 battle. The granite pieces are incised with texts and graphics chosen by the tribes (see above).

Most panels are inscribed with quotes from chiefs and warriors after the tribes had identified those who fought there on that Bloody Sunday. Perhaps the most poignant words are those that have been attributed to Arikara scout Bloody Knife, who was killed during Maj. Marcus A. Reno’s valley fight: “I will not see you [sun] go down behind the mountains tonight.… I am going home today, not the way we came, but in spirit, home to my people.”

The Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (NPS.gov) is open to the public year-round. Summer hours at the park are 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily. Check with the park service for up-to-date operating hours, as they have been adjusted due to the pandemic.

Recommended reading: Jerome A. Greene, Stricken Field: The Little Bighorn Since 1876 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma, 2008)

C. Lee Noyes resides in Morrisonville, New York, with his wife, Michele. Noyes is the former editor of The Battlefield Dispatch, the quarterly newsletter of the Custer Battlefield Historical & Museum Association. He coauthored Last Man Standing: William Spencer McCaskey.