— Courtesy NPS.gov —

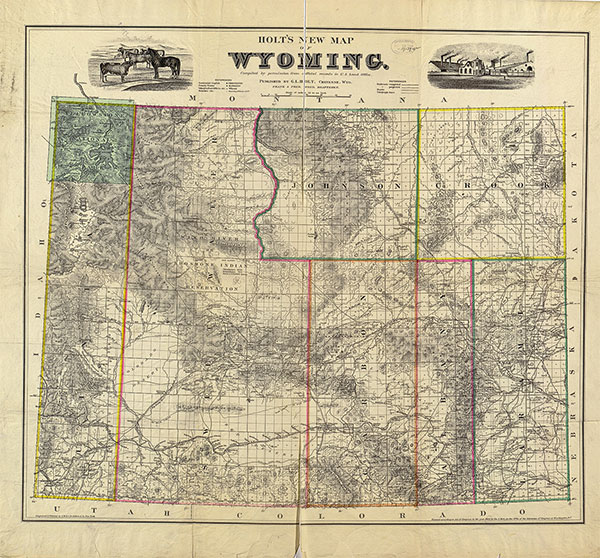

Westbound pioneers driving their wagons across the landscape left deep ruts and shallow swales on their routes as they headed toward the opportunity for free land in Oregon Territory, toward potential riches in the goldfields of California and to a land of religious freedom in Utah. Beginning in 1841 and continuing through the Civil War era, these pioneers traveled the Oregon, California and Mormon trails. The routes had many starting and ending points, but a common area was the funnel as they all crossed Wyoming, most going over the South Pass of the Rockies.

While we often think everybody went west, the truth is after the first few years of overland travel, many also came from the West. And the pioneer image, familiar to all trails, is of wagons being pulled by oxen, mules or horses; with men using packhorses while heading quickly to goldfields.

— Map Courtesy Library of Congress, circa 1883 —

During a short period of overland trail migration, for economic reasons, travelers used their own power to make the journey. At least 2,927 foreign immigrants from England, Scandinavia, Ireland and other European locales made the trip on foot, pushing and pulling small two-wheeled handcarts carrying their goods. These handcart pioneers were Mormons converted to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by missionaries to their home countries. They desired to relocate to the church headquarters in Great Salt Lake City, but most had few resources—certainly not enough money to purchase teams and wagons—and they readily agreed to take part in the handcart migration Church President Brigham Young launched in 1855 and began in 1856.

Using handcarts, Young believed, “They can come just as quick, if not quicker, and much cheaper—can start earlier and escape the prevailing sickness which annually lays so many of our brethren in the dust. A great majority of them walk now, even with the teams which are provided.”

Overland from Iowa City in 1856

— Historic image of Fort Laramie by Ridgway Glover Courtesy MET —

Five companies of handcarts set off from Iowa City, Iowa, during early and mid-summer in 1856 traveling to Utah. The last two companies to head west that year left the Midwest too late in the season and found themselves in Wyoming in October, when severe snowstorms and cold weather created unbearable traveling conditions, leading to extreme challenges, the deaths of hundreds of travelers and the need for rescue parties from Salt Lake City to help the overdue Willie and Martin Companies to reach Utah.

From 1857 until 1860 another five handcart companies also took to the trail. Every group included families ranging from newborn babies to elderly grandparents. Despite their true and faithful desire to reach Utah, almost all faced severe challenges due to the physical demands of following the trail with a handcart.

— Modern photo of Fort Laramie courtesy NPS.gov —

Imagine taking your own family and setting off on this journey across Wyoming. Fort Laramie is the first physical post handcart pioneers saw in Wyoming. The frontier fort served fur trappers and traders, and then became a military post in 1849. For many travelers it was an essential place to rest and resupply, but Mormon trains usually avoided the fort, whose sutlers seldom had provisions. The fort stands today, operating as a national historic site that interprets not only the period of overland migration, but also the fur trade, frontier military and American Indian history of the region. For travelers today, it is easy to see the trail traces as they lead into and away from the fort grounds.

Fort Laramie to Fort Caspar

— Courtesy Gates Frontiers Fund Wyoming Collection within the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress —

Head west from Fort Laramie. You can follow trail markers or use the National Park Service auto tour guide to stay on the route. Take U.S. 26 west and I-25 north. This route passes former Mormon Trail sites including Horseshoe Station and Deer Creek, plus Rock in the Glen (today’s Glenrock).

In 1857, the second year of handcart travel, the Mormon Church made changes to the travel plan. The church started its mail delivery service, the Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company, and established stations for assistance to LDS church members journeying overland. At Horseshoe Creek, a day’s travel west of Fort Laramie, eighteen “brethren from the Valley” built houses to serve travelers. Farther west, at Deer Creek, another 60 Mormons under the direction of Nathaniel V. Jones made a new settlement of log houses in a fort-like fortress. The newly constructed outpost was abandoned the year it was built, however, when the Army approached Utah, intending to install a new governor to replace Brigham Young.

Like other overland routes, the Mormon Trail crosses the North Platte River for the final time at present-day Casper. The 1847 Mormon Pioneer Company left men behind to build a ferry across the North Platte that would serve Mormons and other travelers for years. By the time the handcart companies were in the area in 1856, a bridge was in place over the river, built by John Baptiste Richard (Reshaw).

A replica of Reshaw’s Bridge is at a small town park in Evansville, just below the Oregon Trail Veterans Cemetery. When the 1856 Willie Company came to the site, they found some rough log huts Richard had built and 37 buffalo robes left for their use by Mormon missionary Franklin Richards. Willie’s party traveled on another five miles before fording the river near the site that would become Platte Bridge Station. This location later became Fort Caspar, and is currently a historic site with an interpretive center and replica fort structures, including a ferry similar to the one the Mormons built in 1847.

All handcart companies stopped at Reshaw’s post seeking supplies, then continued westward and forded the North Platte before striking out on the trail toward the Sweetwater River and Independence Rock. Learn about the trail and the last crossing, as well as the story of the Martin Handcart Company, at the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center in Casper.

Handcart Ranch on the Sweetwater

For an opportunity to actually push/pull a handcart on the trail, head to the Handcart Ranch, 60 miles west of Casper near Devil’s Gate. This historic site is now owned by the LDS Church and provides access to an area called Martin’s Cove (federal lands under lease to the church), where members of the Martin Handcart Company became stranded in October 1856. An interpretive center in the old Tom Sun Ranch house provides insight into the handcart migration, but anyone can take a handcart and walk the trail, ford the Sweetwater River and learn firsthand what it is like to walk in the footsteps of these determined pioneers.

Farther west, where the trail crossed the Sweetwater River for the sixth time, and near where the 1856 Willie Company became mired in cold and snow before being rescued by men from Salt Lake City, a new interpretive center also shares the story of the handcart migration; this telling is based on the experiences of the Thomas Moulton family, who left England in May 1856, and reached Utah in November that year.

South Pass to Fort Bridger

— Illustration of Hand Cart Pioneers courtesy Utah Historical Society —

South Pass, the key to overland migration routes, lies to the west and it is possible to follow the trails over the pass by walking or driving. For those less adventuresome, drive U.S. 287 north then U.S. 28 west to cross the pass and then continue across the Red Desert to Fort Bridger, a trading post built to serve travelers after 1842. This is now a state historic site with a replica of Jim Bridger’s original trading post, and other authentic military-era buildings. An archaeological excavation outlines the foundation of the fort’s period of Mormon ownership.

As you travel this handcart trail, leave the snacks behind and let your children understand the difficulties the travelers faced. With only small carts, the handcart immigrants simply could not haul all the food they needed for survival. They were not good hunters, though they did manage to harvest a few bison, sage chickens and catch some fish in the creeks and rivers. But most went hungry much of the time.

— Devil’s Gate Photo Courtesy NPS.gov —

After leaving Devil’s Gate and traveling through the Sweetwater River, one pioneer wrote:

“The people are geting weak, and failing very fast. A greate many Sick. Our teams are als[o] failing fast and it requires great exertion to make any progress.”

The children began chewing on strips of rawhide pulled from the handcart wheels or the boots of people who died. They stripped bark from willow trees and gnawed on it, trying to ease the hunger in their bellies.

John Oborn, who was 12 that year, wrote:

“We resorted to eating anything that could be chewed; even bark and leaves of trees. We youngsters ate the rawhide from our boots.”

Despite the disastrous crossings of Willie and Martin—the worst single disasters encountered by any overland travelers—the church continued supporting the handcarts. From 1857 until 1860 another five companies of people from the British Isles and Scandinavian countries trudged the trail with their two-wheeled carts. More would die, but most safely reached Utah.

Candy Moulton is the author of The Mormon Handcart Migration: “Neither Tounge Nor Pen Can Tell The Story,” newly released from the University of Oklahoma Press. She traveled with the Mormon Trail Sesquicentennial Wagon Train in 1997, pushing and pulling a handcart for part of the journey.