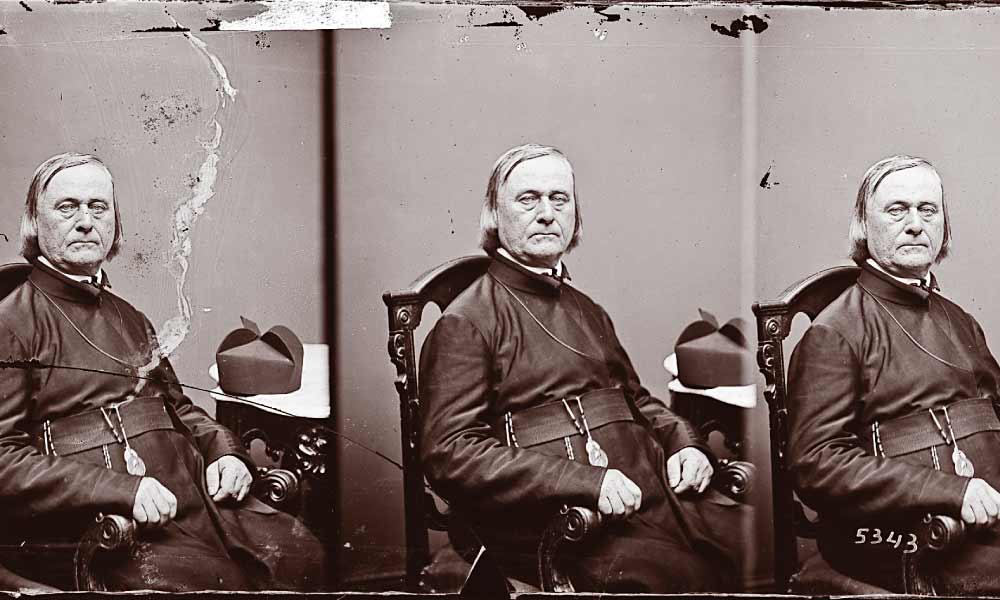

– Mathew Brady, Library of Congress –

At age 20, Pierre Jean De Smet

left his native Belgium and came to America, where, in 1821, he entered the Jesuit novitiate in Maryland. He studied for the Jesuit priesthood in Florissant, Missouri, where he took his vows in 1827.

Fr. Charles Nerinckx had inspired De Smet to make the life-changing decision when the priest visited the Preparatory Seminary at Mechelen in Belgium in search of recruits for his mission in Kentucky. The idea of working with Indian tribes appealed to De Smet, and though he never worked in Kentucky with Father Nerinckx, he would ultimately take his religion into the West.

De Smet was in St. Louis in 1831 when the Salish tribe, and later the Nez Perce tribe, sent emissaries to the city seeking “black robes” to come into their country. Hudson Bay Company trappers and Iroquois trappers, working along tributaries of the Columbia River, had told the Western tribes about the men who wore black robes.

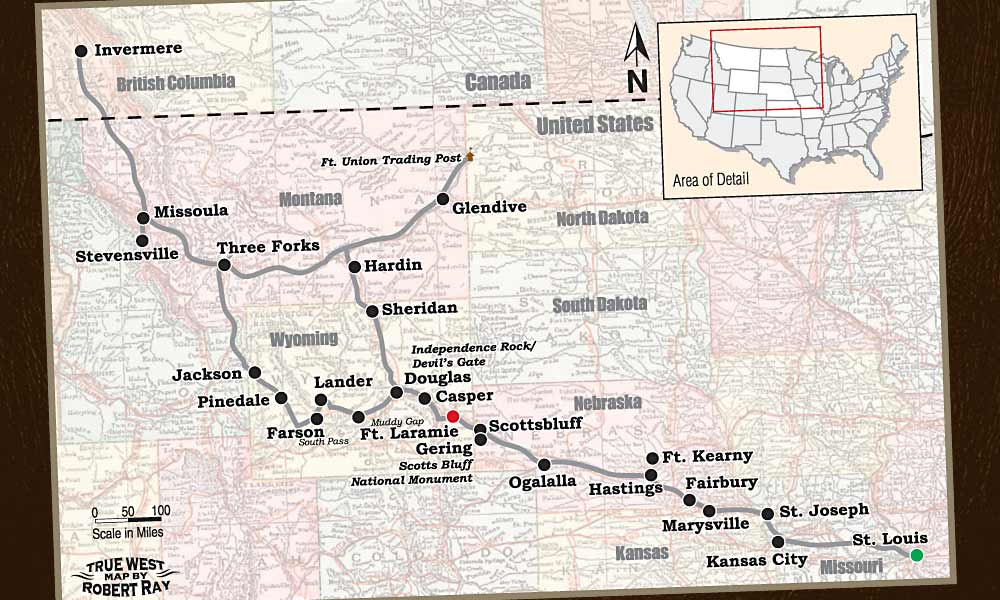

In late March of 1840, Father De Smet left St. Louis with an American Fur Company brigade. He traveled with them over much of his route as he responded to the appeal from the Salish tribe for a mission. This priest would spend the remainder of his life traveling not only in the West, where he established missions and participated in important treaty negotiations with the tribes, but also around the world. He made more than one trip back to Belgium and other European countries, seeking funds for his work, sailing around Cape Horn or traveling across the Isthmus of Panama. The log of miles he journeyed is estimated at no less than 180,000 and perhaps as many as 260,000 miles on foot or on horseback, and by boat, ship and train.

De Smet had first worked with the Potawatomi people, for whom he helped establish St. Joseph’s Mission in present-day Council Bluffs, Iowa. But his early training was in the St. Louis area, where we begin following his Western journeys.The Trail Begins in St. Louis

The Jefferson Expansion Memorial and Gateway Arch in St. Louis serves to launch our journey westward. Though closed now for renovations, this national park site is developing all new exhibits and experiences showcasing the westward expansion. The Old Courthouse, located across the street, has a free exhibit gallery that focuses on the settlement of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, development of early St. Louis, and settlement of the Great Plains.

St. Charles, Missouri, just west of St. Louis, served the fur trade and was a campsite of the Lewis and Clark expedition. This charming town, founded by a French Canadian fur trader, has a compact downtown historic district that includes Missouri’s First State Capitol, which was in use from 1821 to 1826. You can take one of the regularly guided tours.

The fur caravan Father De Smet joined

as he left Missouri in 1840 departed from Westport, Missouri—now part of the Kansas City metro area. The caravan followed a route that would become the Oregon Trail. Visit the Frontier Trail Museum in Independence, Missouri, for an introduction to the trail. At the museum

you can pick up an automobile tour guide that will take you on the trail route across Kansas

and Nebraska to Fort Kearny. Fort Kearny, established in 1847, became an important way stop for travelers headed to Oregon and California. The fort has been reconstructed as a Nebraska State Historic Site.

From Fort Kearny take Highway 30 west and enjoy the journey along the trail to Ogallala, then follow U.S. 26 and the North Platte River to Scotts Bluff, now a national monument. The main trail goes through Mitchell Pass at the base of Scotts Bluff, but an earlier route was farther south over Roubidoux Pass, named for the fur trading family that established a post there in 1851. Robidoux Pass and a replica of the trading post are just a short drive southwest of Scotts Bluff via Highway 71 and Carter Canyon Road.

-Map True West Archives-

The Trail to the Rockies

The American Fur Com-pany established its own trading post—Fort William, later called Fort John and, ultimately, Fort Laramie—at a site some fifty miles farther west. De Smet visited here more than once in his years in the West, most notably serving as an emissary for the Indian tribes for the 1851 Horse Creek Treaty.

The Oregon Trail continues west (take U.S. 26, then I-25 through Casper) and on toward Muddy Gap on WYO 220. De Smet and the fur brigade reached Independence Rock on June 14, 1840, where he carved his name in the granite, the first priest to have reached the remote spot. At Devil’s Gate just a few miles to the west, the Sweetwater River cuts through the Rattlesnake Range, which rises, as he wrote, “perpendicularly to a wonderful height” and results in a forced passage as the water is “now rushing with fury, then swelling with majesty.”

Rendezvous that year took place on Horse Creek, north of Pinedale, Wyoming, near the present small community of Daniel. On a hillside overlooking the rendezvous ground, De Smet on Ju ly 5, 1840, held the first Catholic mass in what is now Wyoming. To learn more about the rendezvous, and obtain directions to the De Smet mass site, visit the Museum of the Mountain Man in Pinedale.

Our route now heads north on Highway 191 to Jackson Hole, then along Highway 22 over Teton Pass into Idaho, and north on U.S. 287 into Montana. De Smet preached a third mass (the first in Montana) in August of 1840 at the Three Forks of the Missouri. He was still short of his intended destination in the Bitterroot Valley, and actually abandoned the trek west to return to St. Louis and raise more funds before returning and establishing the mission at St. Mary’s in the Bitterroot Valley in present-day Stevensville.

In coming years Father De Smet would work with other priests, notably Father Antonio Ravalli, to establish additional missions in Montana and Idaho, including St. Ignatius among the Flatheads in Montana (which was abandoned, though now there is another St. Ignatius Mission that dates to 1890), and Mission of the Sacred Heart near Coeur d’Alene in Cataldo, Idaho.

The Black Robe’s travels took him north along the Kootenai River into British Columbia, Canada, where the North West Fur Company had established Kootenai House. This story is told at the Windermere Valley Museum in Invermere, British Columbia, where you also will be able to get directions to the Kootenai House site.

– NPS.gov –

Treaties and Trail’s End

On one of his journeys, Father De Smet traveled east across what is now northern Montana heading down the Missouri River to Fort Union Trading Post, where in 1851 he assembled a party of about 35 men that included headmen from the Assiniboine, Minnetaree, Mandan, Crow, and Arikara tribes, along with scouts, Métis, and Canadian wagon masters whom he persuaded to attend a great Indian council to be held at Fort Laramie. The tribal members trusted him, and the government officials planning the treaty council believed he could aid in the negotiations that would lead to compensation for the tribes in exchange for recognition of the road to Oregon and California.

De Smet and his party left Fort Union on the Missouri River and traveled south. To follow his general route, take Montana Hwy 16 and Montana 200 to Glendive, Montana, then I-94 west and Montana Hwy 47 south to Hardin. From Hardin follow I-25 south through Sheridan, past Lake De Smet, named for the priest, to Casper and Douglas, Wyoming, then take U.S. 26 to Fort Laramie.

Although the 1851 treaty negotiation was to take place at Fort Laramie, the tribal response was so massive—approximately 10,000 Indians showed up with their huge horse herds—it had to be moved downstream to a site on the current Wyoming-Nebraska border at Horse Creek. This first major treaty with the Northern Plains tribes formally

recognized the Oregon-California road, which was already in heavy use by Euro-Americans. The treaty also sectioned off Indian lands, presumably keeping them for all the tribes. The tribes were to receive compensation, but as happened with other treaties negotiated with tribes earlier—and would happen in the future as well—the delivered goods were far short of what was promised.

De Smet wrote that while attending what he called the Great Council, he had offered “the holy sacrifice” in a space where “some lodges of buffalo-hides were arranged and ornamented as a sanctuary.” He held daily conferences on religion with the Indians, “some-times with one band, sometimes with another,” and he also baptized hundreds from the many tribes represented.

In his account of this significant treaty council, De Smet wrote, “During the eighteen days that the Great Council lasted, the union, harmony and amity that reigned among the Indians were truly admirable. Implacable hatreds, heredity enmities, cruel and bloody encounters …were forgotten. They paid mutual visits, smoked the calumet of peace together, exchanged presents, partook of numerous banquets, and all the lodges were open to strangers.”

After the 1851 Horse Creek Treaty council, De Smet continued his travels throughout the West, making trips to Astoria and Vancouver, to the Idaho

and Montana missions

and to other locations. He also traveled to Europe to continue raising funds

for the missionary work.

He met with Lakota leaders prior to the 1868 treaty

negotiated at Fort Laramie before he returned to St. Louis, where he died in 1873.

Candy Moulton is a veteran road warrior who hangs her hat near Encampment, Wyoming, when she is not exploring the West for one project or another.