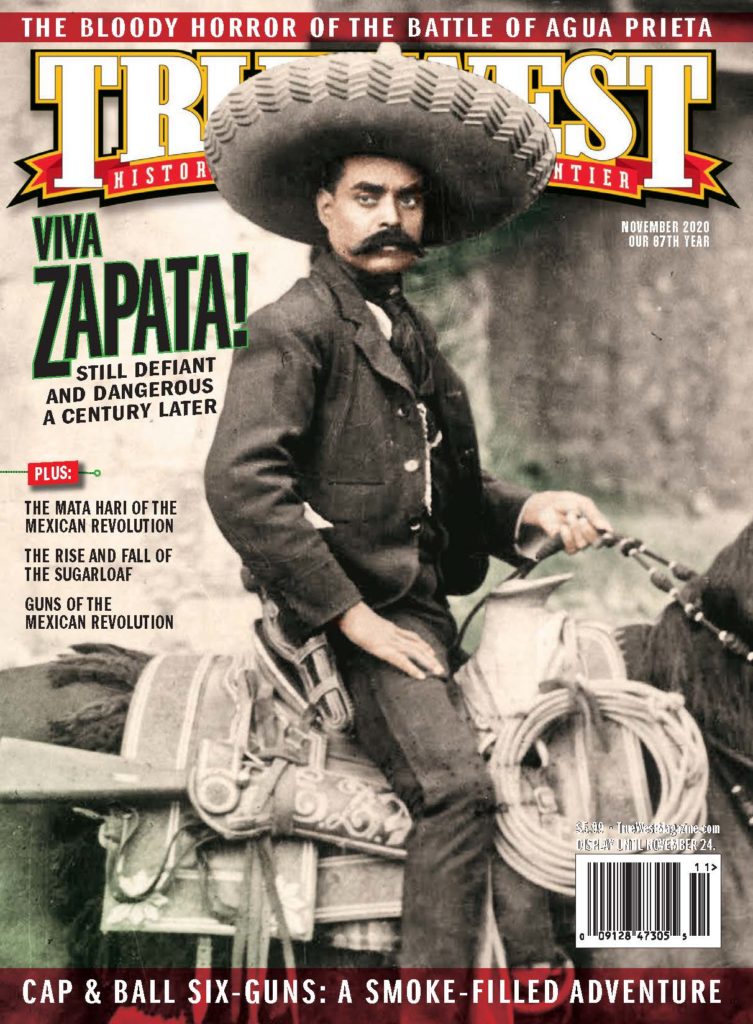

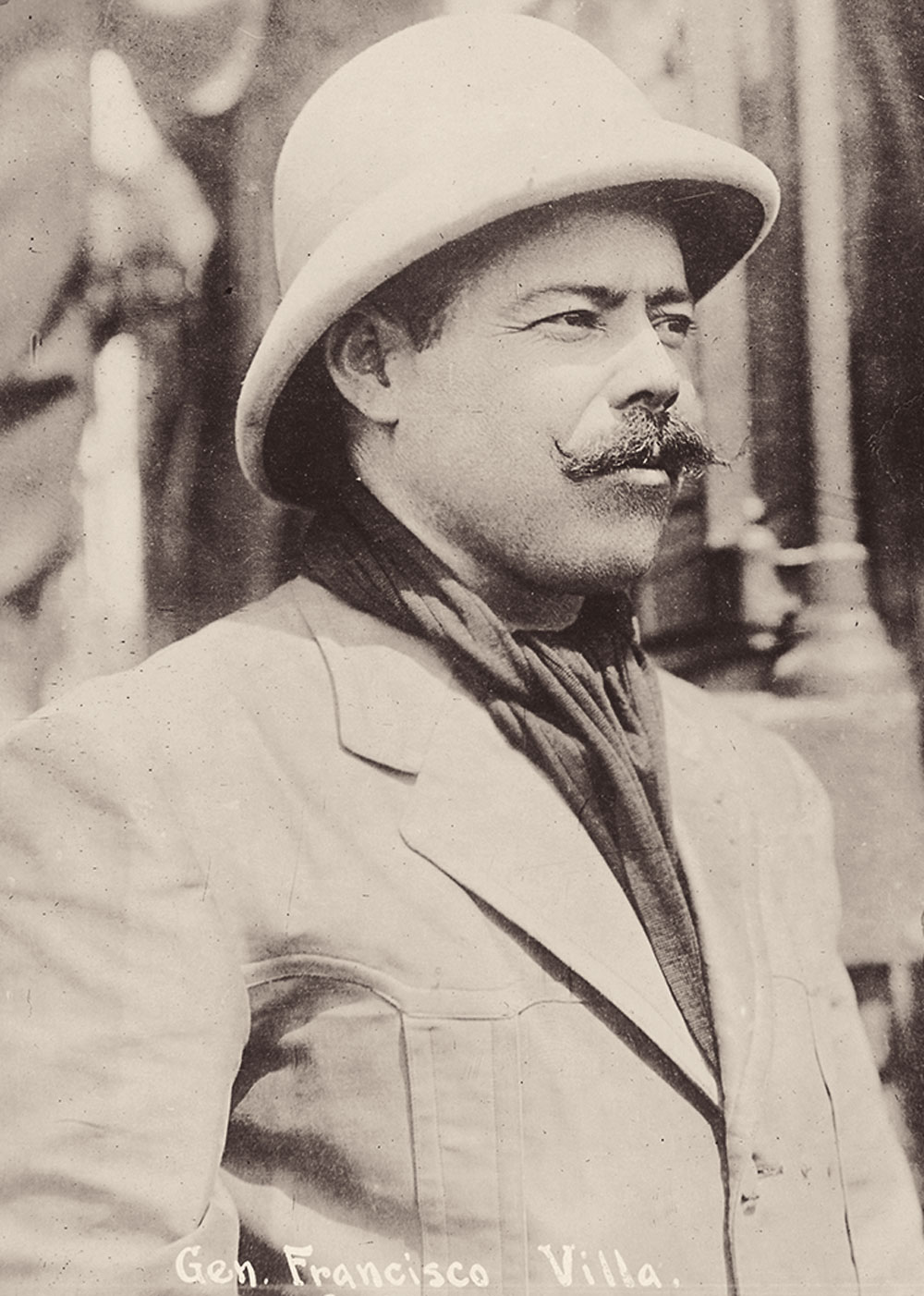

Although Pancho Villa—whose real name was Doroteo Arango—is the best-known figure of the Mexican Revolution, Villa would perhaps never have gained such recognition were it not for Porfirio Díaz.

In many respects, Díaz was an outstanding, accomplished president. To a large extent, he modernized the country, opened schools and encouraged business. One of his greatest achievements involved lacing the nation with railroads, which exposed the country to additional trade, particularly with its northern neighbor, the United States, a powerhouse otherwise known—and often feared—throughout Mexico as the “Northern Colossus.”

Despite his initial popularity, most historians today consider Díaz as corrupt as the government he led. Little economic improvement filtered down. While Díaz brought relative peace to Mexico, he also brought centralized tyranny.

Revolt Against President Díaz

As president of Mexico since May 1877 (aside from stepping aside for one term), Díaz found himself confronted by sporadic, northern Mexico revolutionary outbreaks in mid-October 1909. A year later, for Mexico’s celebration of its centennial of independence from France, President Díaz invited the world’s most powerful and wealthy to the capital, plying them with imported delicacies and pageantry. But this man, whose Mexican bloodline also was predominately Indian, ordered other Indians off the streets, lest their poverty offend visitors.

By early 1910, these outbreaks took place particularly across the Rio Grande from El Paso—the northern riverside neighbor of Juárez. From this Juárez borderlands would arise the intellectual and predominate storm center of the approaching Mexican Revolution.

But why would a revolutionary movement essentially commence so far north in Mexico, especially alongside the Rio Grande, a site where bullets might rain on El Paso? The answer was location, location, location. Neighboring El Paso offered refuge, transportation, weapons, communications, freedom of movement and a sympathetic population of Mexican exiles and American nationals. As the largest Mexican community leaning against the international border, El Paso became an uneasy haven for Mexican revolutionaries. Rebel clarion calls from there found listeners and advocates on both sides of the Rio Grande.

Rise of Francisco Madero

Díaz carried a heavy stick, retaining a relatively trained, well-equipped army. Still, it was an army rife with graft, with men serving not always because they wanted to, but because they were forced to. Díaz was not so much a president, as he was a dictator.

Poorly led but nearly impossible to suppress, the uprisings did little more than provide President Díaz’s army with an opportunity to drench portions of the nation in blood. Yet the federal army’s inability to ensure peace also meant it could not ensure national stability.

The radicals, themselves, were rarely military leaders, in the accepted sense, as their primary strength laid in arousing and stimulating passions. So military leadership fell to Francisco Madero, a staunchly liberal but wealthy Mexican, who had been born in Coahuila on October 30, 1873. In San Antonio, Madero had written what he called his “Plan of San Luis Potosí”—named for the Mexican city in which he had formulated it. This whistling indictment of the Díaz regime, a tract laced with incendiary charges and accusations, called for restricted presidential terms. It also proclaimed Juárez as the provisional capital of national government, even though that community was federally occupied.

As one violent incident followed another, President Díaz sent one-fifth of his ragged army north to contain the rebels. By New Year’s Eve 1910, federal soldiers were patrolling Juárez. The Juárez Society of First Ladies did not dance. Juárez civil authorities compelled every adult male in town to step before the mayor and declare insurrecto innocence or admit guilt. Those who could not prove their innocence were shot. Meanwhile, over in El Paso, circulars in Spanish pleaded for regional sympathizers to rise up and help overthrow the dictator.

As violence intensified in Juárez, eight riderless Mexican cavalry horses galloped north across the Stanton Street international bridge into El Paso on February 2, 1911, following the Battle of Rancho Madia, near San Ignacio, Chihuahua. Blood splattered their saddles. Fifteen additional riderless horses arrived in El Paso a half hour later.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Villa Takes Charge

With events churning toward a Juárez showdown, as Mexican soldiers, led by the capable Gen. Juan Navarro, patrolled the streets, Madero hesitated. To attack Juárez and possibly lose would mean the probable end of his career and, perhaps, his life and liberty. Therefore, Madero blinked; he decided the ancient community of Casas Grandes, 145 miles south, was a more effective initial target. The area had been abandoned by Pueblo farmers and was primarily a railroad stop, with its principal buildings clustered around a central plaza. Madero assumed that from this remote area, he could choke off incoming supplies to Juárez—and capture the bordertown later.

He assumed incorrectly, and lost the battle of Casas Grandes, with The El Paso Herald reporting 57 dead Mexican insurgents and 40 captured, of whom 16 were Americans and two were Germans.

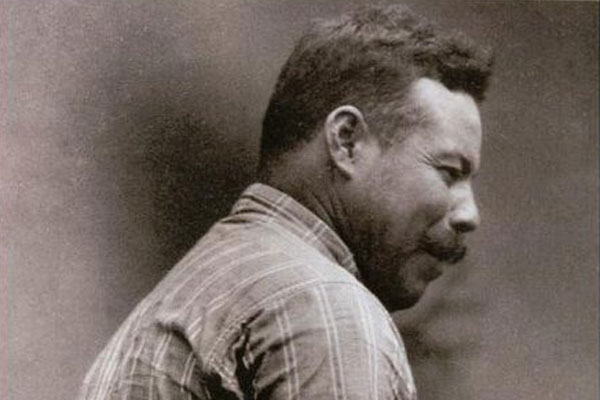

Pancho Villa, however, was not afraid that an attack on Juárez could hit El Paso, north across the Rio Grande from Juárez—and lead to problems with the U.S. While El Pasoans had fears of bullets dropping on their city, they nevertheless largely supported the Revolution. The top (fifth) floor of the downtown Caples Building in El Paso became a revolutionary headquarters, among other things, luring American soldiers-of-fortune to the cause from all over the United States. And the El Paso Sheldon-Payne Arms company, near the international bridge, not only advanced money for weapons freight charges, but also refrained from charging commissions. After the shooting started at Juárez in May, many insurrectionists became popularly known as the Trenta-Trenta Muchachos, the “30-30 Boys.”

When Gens. Pascual Orozco and Villa won the decisive battle in Juárez, the capture forced Díaz to abdicate his rule. Madero stepped in as Mexico’s president. Yet the rebels viewed Madero as a weak leader, and the Mexican Revolution continued to rage. Juárez fell at least 10 times during the revolution, making it—in my judgment—the most fought over city in North America.

Although most folks believe the Mexican Revolution commenced with Villa’s raid on Columbus, New Mexico, in March 1916, it was this initial fall of Juárez, with the help of its neighboring American city El Paso, that truly fired the opening volley.

The Mexican Revolution came to a close by the end of 1920. Villa retired, and Álvaro Obregón, who had brought relative peace to the nation, was elected president.