True West Archives

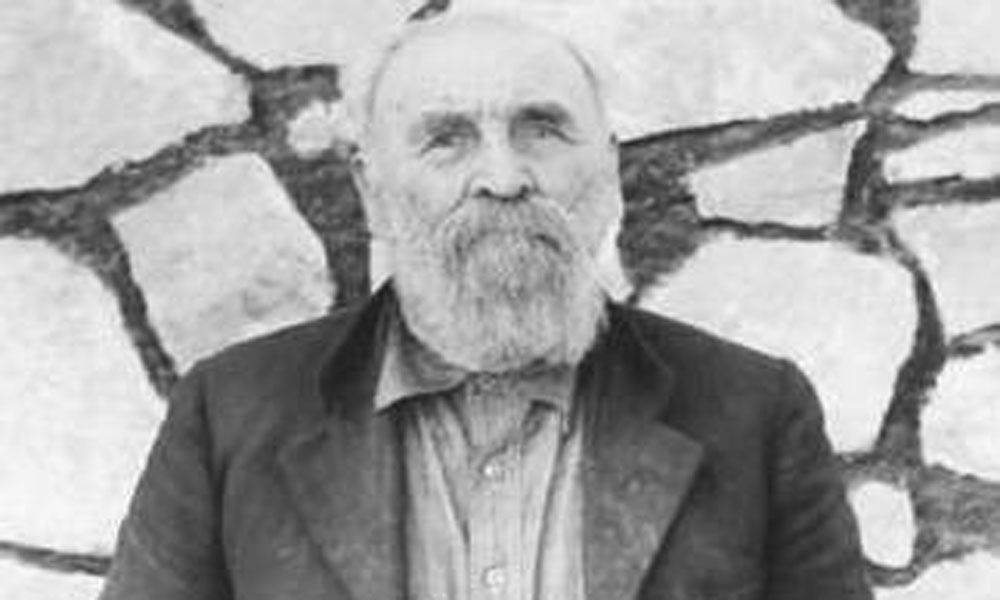

Were Wayne Brazel—involved in the killing of Pat Garrett—and Mac Brazel—involved in the 1947 Roswell UFO incident—related?

True West Maniac #697 (Mansfield, Ohio)

I reached out to award-winning author-historian Heidi Osselaer who has done a lot of research on the Brazels. “Yes, Mac and Wayne Brazel were related—Wayne’s father was the brother of Mac’s grandfather. Those Brazel brothers were great pals with Oliver M. Lee, W.W. Cox, Albert Fall and that whole group who were involved with range wars, feuds, charged with attempted murder and other fun stuff! And of course, those men are believed to have been behind Pat Garrett’s assassination.”

How prevalent were “no-carry” laws in the Old West?

Jeff Arnold (Indio, California)

Those old “check your weapon” laws were put into place in frontier towns for a good reason and that was to keep the drunks from killing each other for no reason. They could settle an argument with their fists if they didn’t mind getting busted knuckles. If a lawman used the barrel of his Colt to “buffalo” a drunk, locking him up for the night and giving him a small fine was much better than shooting him.

But most of those laws were local. Western states with a lot of wide-open spaces couldn’t enforce “no-carry” in places where guns were absolutely necessary for protection, hunting for food, etc.

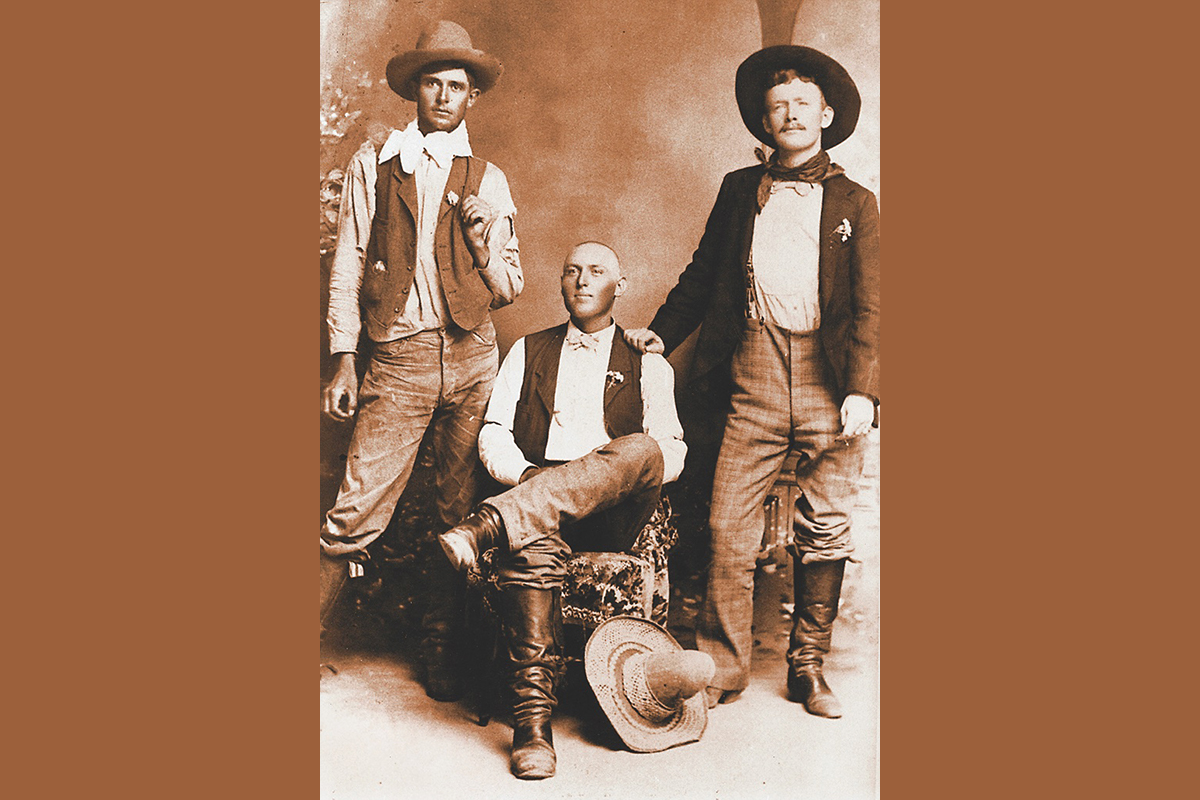

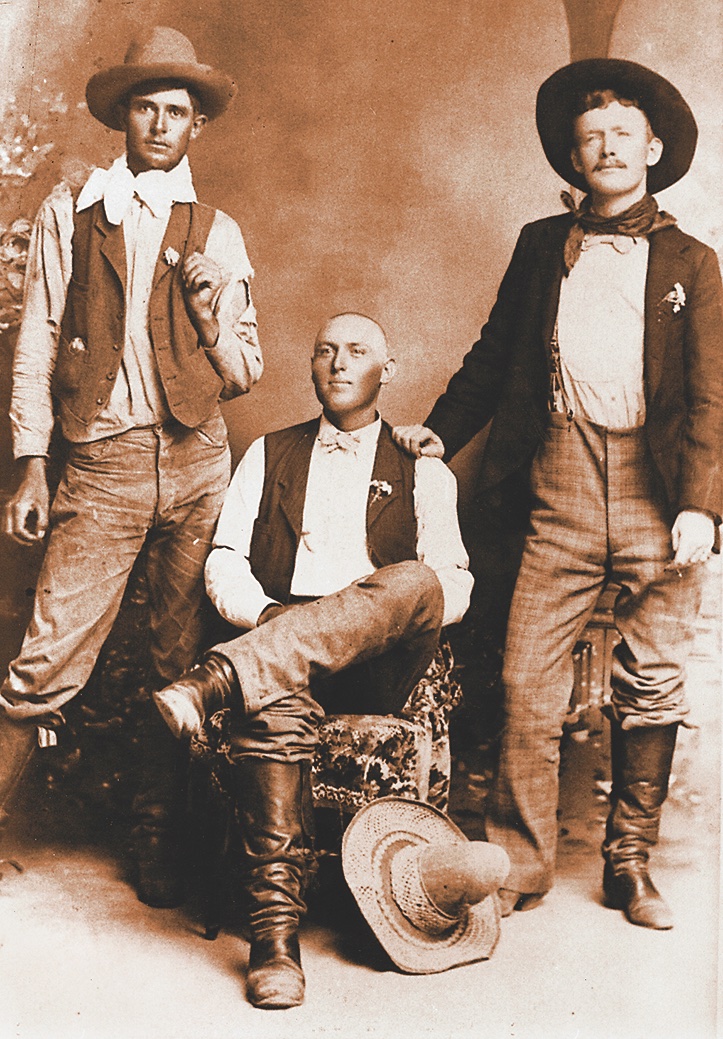

Many of those photos you see of gun-toting cowboys are studio photos, and the pistols aren’t loaded. Cowboys loved to get fancy duds on, pack smoke wagons and have their photo taken.

In my research of Old West figures, I frequently read, “He/she was buried, in a certain place-year, and then reinterred in so and so cemetery.” How often did that happen?

Mark Liveris (Highlands Ranch, Colorado)

That happened quite frequently and still does. It usually happens when a man, woman or child dies far from home and the family wishes to have them buried in a local cemetery. It also happened with soldiers killed in action. I had a friend shot down over North Vietnam in 1967. His body wasn’t recovered until just a few years ago. The remains were re-buried with full military honors in the Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. There may be few remains, but any amount at all still gives a family closure.

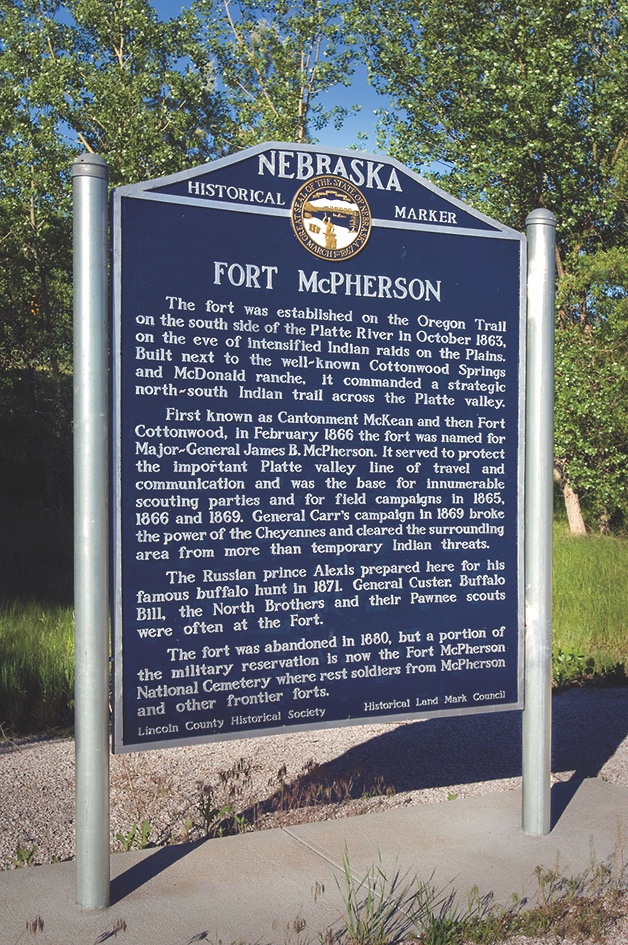

Courtesy Nebraska Tourism

What was Gen. George Crook’s General Order #10?

Shawn Cote (Fort Fairfield, Maine)

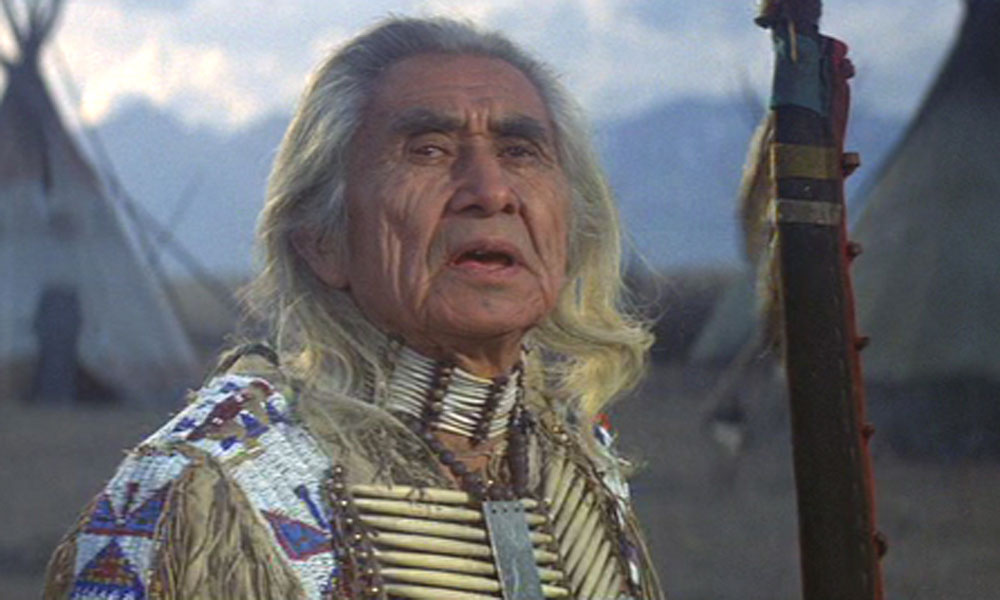

General George Crook’s General Order No. 10 on November 21, 1871, declared that “all roving bands of Apache Indians are required to go upon their reservations by February 15th 1872. On and after that date all Apache Indians found outside their reservations will be considered and treated as hostile.”

Reservations were established at Apache, McDowell, Date Creek, Grant, Verde, Beale’s Spring and San Carlos in Arizona and Tularosa in New Mexico by President Grant’s peace commissioner, Vincent Colyer. This established a defined field of operation. Crook sent messages out to all the Apache bands that they must report to their designated reservations by the middle of February. Any who did not report would be branded as “hostiles.”

Naturally, when spring came and the weather abated, various bands bolted from the reservation. Although many Indians moved to their assigned reservations, thousands preferred to stay free. The raiding, depredations and killing continued.

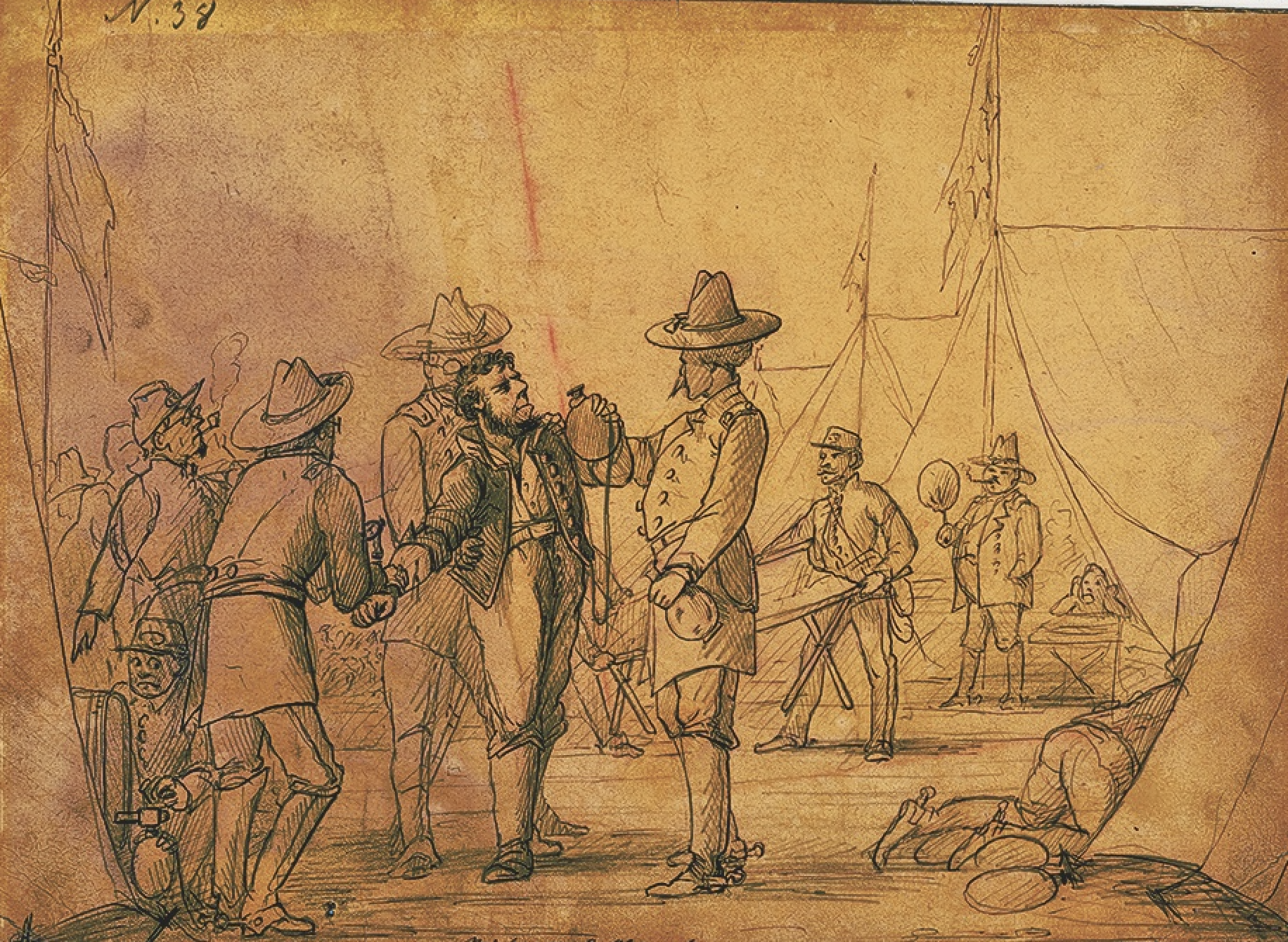

Courtesy Library of Congress

Were Wayne Brazel—involved in the killing of Pat Garrett—and Mac Brazel—involved in the 1947 Roswell UFO incident—related?

How were snake bites treated before antivenoms?

J.R. Sanders (Yucaipa, California)

A common treatment was the ubiquitous cure-all—whiskey—but alcohol only speeds up distribution and absorption of snake venom. Another was the “cut and suck” (as shown in numerous movies and TV shows). Neither is recommended today. Neither are tourniquets. Still another was to put some gunpowder on the bite wound and light it.

When all hope was failing, the victim could hope for a “dry” bite where little or no venom was injected into the wound. That happened, but not often.