Tim Peterson’s breathtaking collection is coming to Scottsdale.

Tim Peterson was just entering his teens in the 1970s when he and his father visited a gallery, and his life took a new direction.

By then, he’d already started collecting—baseball cards, beer cans—but here was a hunting scene that ignited a lifelong interest in collecting the Old West.

He focused on Lewis and Clark, anything to do with the earliest pioneers and American Indians, and then a category special all by itself.

“I am fascinated by people willing to dedicate their lives to a project,” he tells True West. “It’s outside the realm—the majority of people would never do it. And at the end of the journey, they’re often forgotten and financially destroyed.”

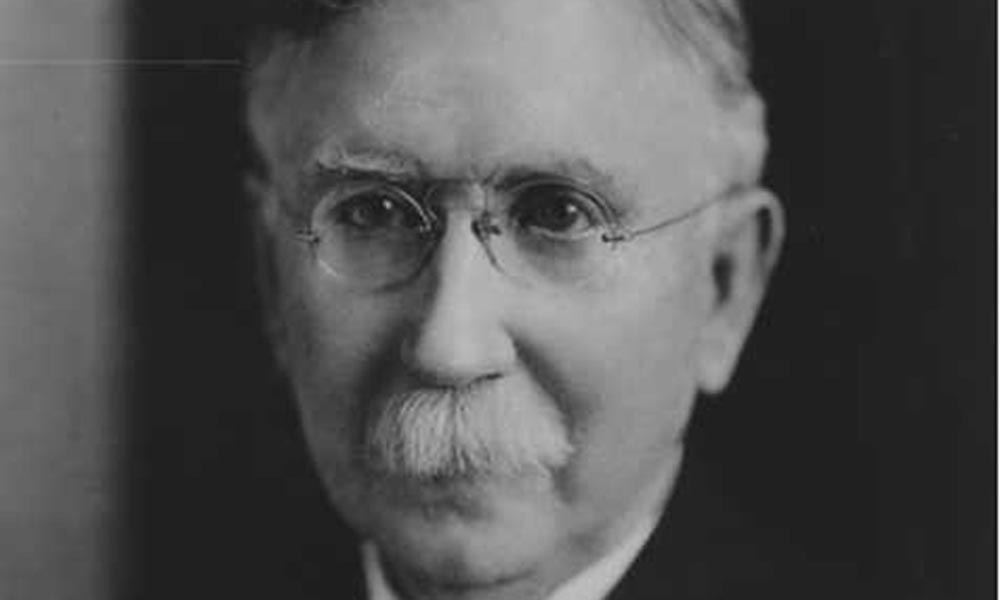

That’s a shorthand description of the life of Edward S. Curtis, an early photographer who put all his creative eggs in one basket and then found the market didn’t care.

Thankfully, collectors like Tim Peterson did care, and today The Peterson Family Collection includes hundreds of Curtis photographs of America’s Native people. Peterson has curated an exhibit of his collection at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West that premieres October 19: “Light and Legacy: The Art and Techniques of Edward S. Curtis.” Tricia Loscher of the museum assisted in the exhibit that runs through late spring of 2023.

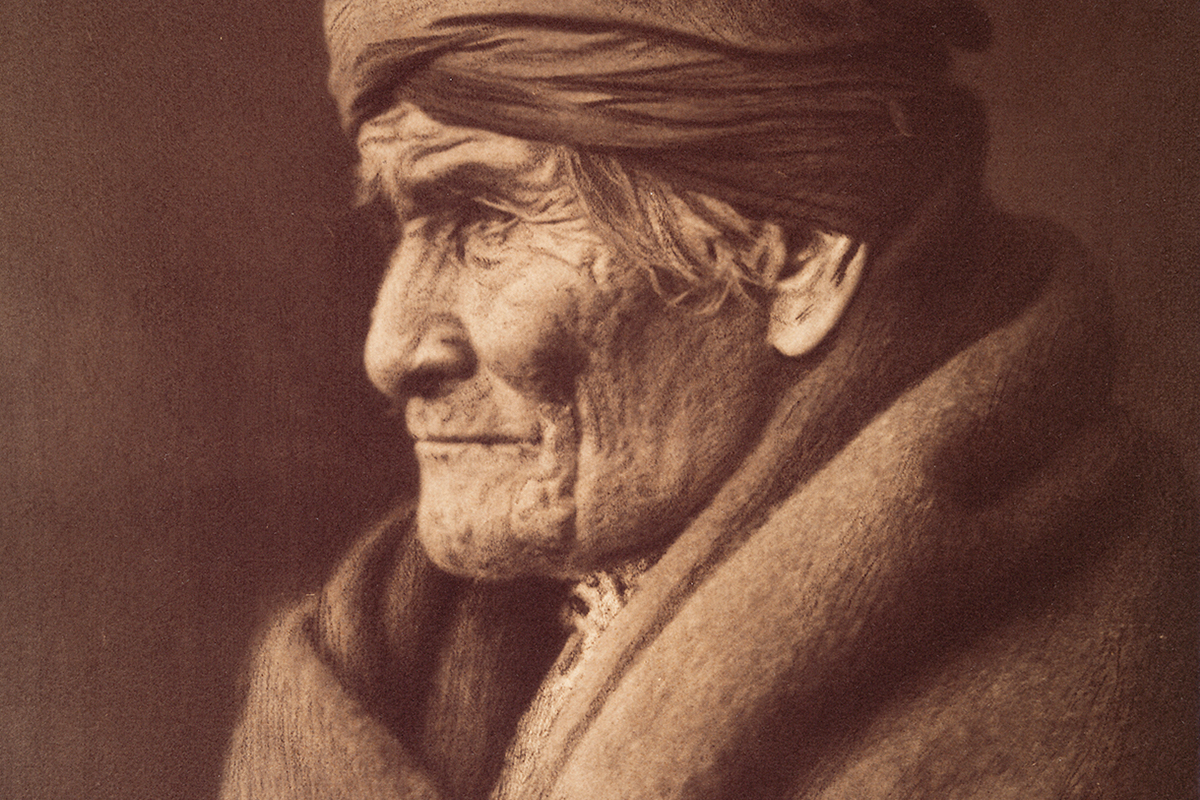

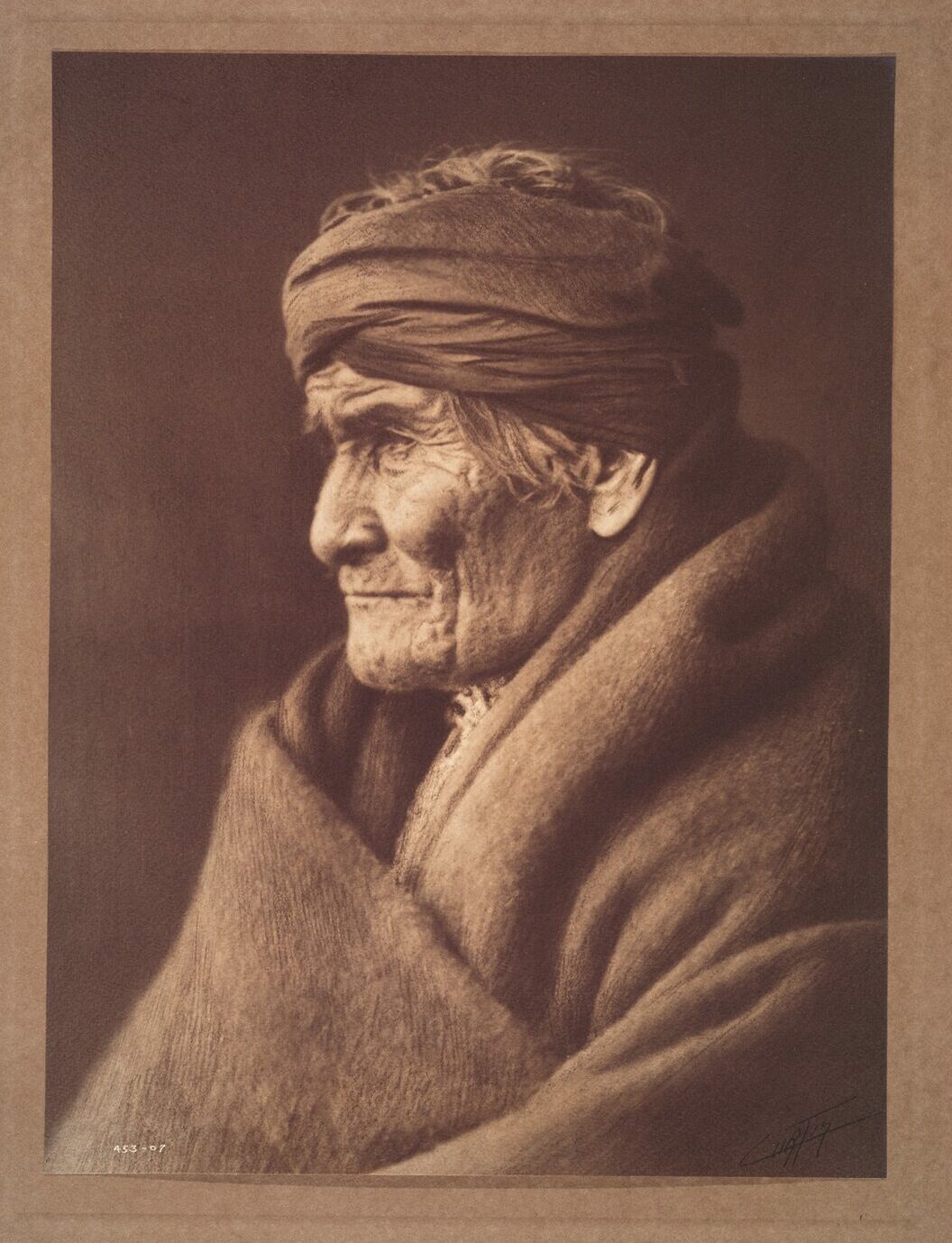

Starting in 1875, Curtis spent 30 years taking over 40,000 photographs of more than 100 tribes and nations throughout the West that he saw as “one of the greatest races of mankind.” It became the largest anthropological enterprise ever undertaken in the U.S.

Curtis thought he was photographing the “vanishing” American Indian—after all, their traditional ways of life were being destroyed as they were forced onto reservations; their traditions were being banned; and their chiefs were dying out or being imprisoned.

Courtesy Scottsdale’s Museum of the West

The first photo of an Indigenous person he ever took was of a woman—Princess Angeline, eldest daughter of Chief Seattle. She was also known as Kick-Is-Om-Lo. “I think it’s significant that his first photo was of a woman,” Peterson says. “Angeline had such determination and strength.”

Curtis did taste success: winning a gold medal and the grand prize the first time he entered American Indian images in a photography contest; getting the backing and support of luminaries of the day: Theodore Roosevelt, J.P. Morgan, the head of the Audubon Society, a founder of National Geographic, the first leader of the U.S. Forest Service. Edward Curtis had every reason to believe his work would be acclaimed and a financial success, but that’s not what happened. Curtis was notoriously broke all the time and often seen as a upstart whose dream was too big to realize.

He poured all his talent into a 20-volume series titled The North American Indian. Roosevelt wrote the intro. Morgan paid the bill. But when the series was published in the 1930s, America was consumed by the Great Depression, and its fascination with Native people had waned, so the work was largely ignored. Curtis died in 1952, never reaching the acceptance and success he had expected. It was 20 years later in the 1970s, when a Santa Fe gallery owner found a treasure trove of Curtis’s copper plates in the basement of a Boston bookstore, and interest in his work was revived.

Peterson was taken with what he saw and not only began collecting Curtis photos but studying his life.

“I found his portraits incredibly telling of a culture that feels dignity and strength, yet the sadness of being altered dramatically.” Peterson says.

He notes that Curtis was one of the first non-Natives allowed into sacred rituals. “Scholars weren’t allowed, but they weren’t willing to spend 10 years developing relationships, either.”

Michael Fox, director of the Scottsdale museum, says they’re thrilled Peterson is bringing this exhibit there. “This is the most significant collection that’s ever been amassed for this artist,” he notes.

Silver Bromide Photograph Courtesy The Tim Peterson Family Collection

Curtis would have adored such attention in his lifetime, but it’s thanks to dedicated collectors like Peterson that he’s getting his day now. Controversy and all. Curtis has been criticized for sometimes staging portraits with traditional clothing when that wasn’t the dress of that day. “No man is perfect, and everyone has flaws,” Peterson noted. “It’s easy to criticize someone, but if there was no Curtis, we’d have lost a lot of imagery of Indian traditions—we’d have lost their sense of pride of their history.”

In 2017, the International Photography Hall of Fame inducted Edward S. Curtis into its acclaimed ranks. And Peterson highly recommends a 2011 book by Timothy Egan: Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis. The book has been widely praised as a “riveting biography of an American original.”

Peterson wants people to take two things from the exhibit: “I hope people learn something about how photography and art can be one in the same, and I hope people appreciate that Edward Curtis attempted to preserve the beauty and dignity of the Indian culture.”

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written three true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.