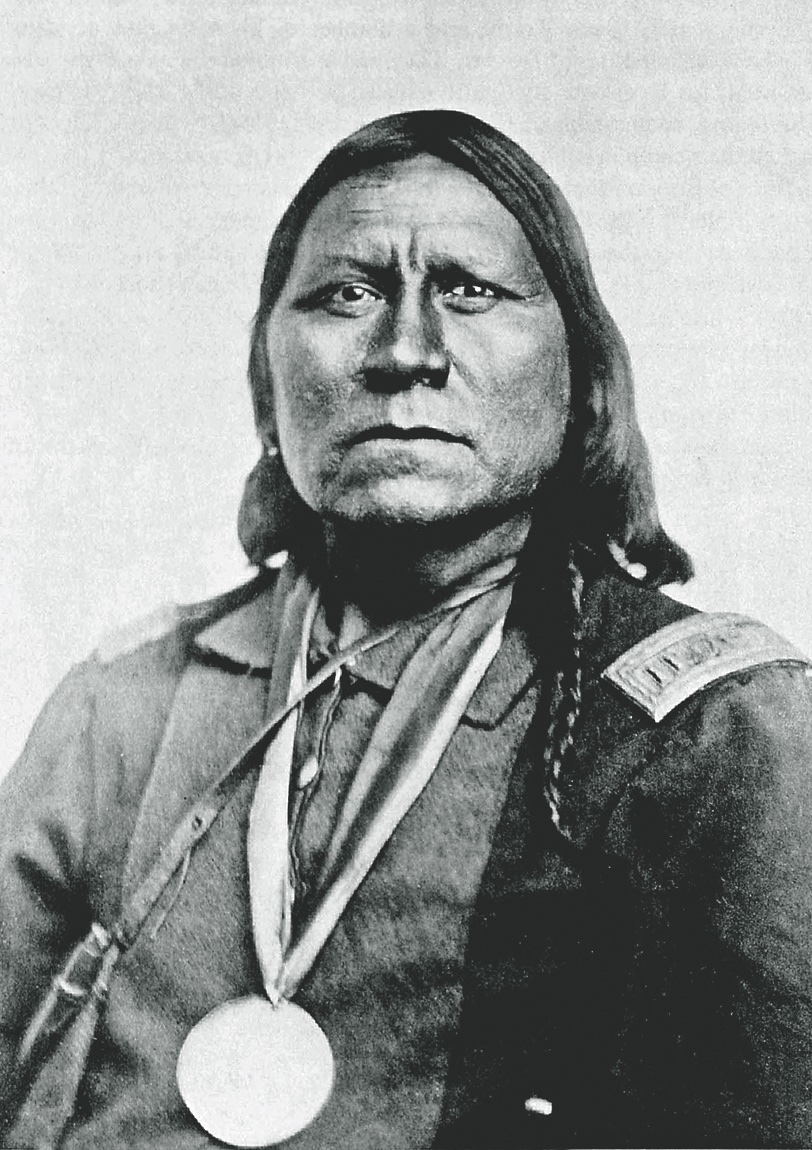

Photo by William S. Soule, True West Archives

Hit the road across Oklahoma and Texas to discover the history behind the Warren Wagon Train Raid and the Kiowa Indian Trial of 1871.

It started out as a run-of-the-mill job. Capt. Henry Warren had a contract to deliver supplies to the forts on the Texas frontier, and in the spring of 1871, Warren and his teamsters left Mansfield, Texas, with five wagons loaded with cornmeal and flour.

Mansfield had been a mill mecca since before the Civil War, when Ralph S. Man and Julian Feild built the Man and Feild Mill—the first in North Texas to use steam power. The town that grew up around it became Mansfield because people just weren’t used to spelling F-E-I-L-D. (Today, that mill heritage is showcased at the Man House Museum and the Mansfield Historical Museum & Heritage Center.)

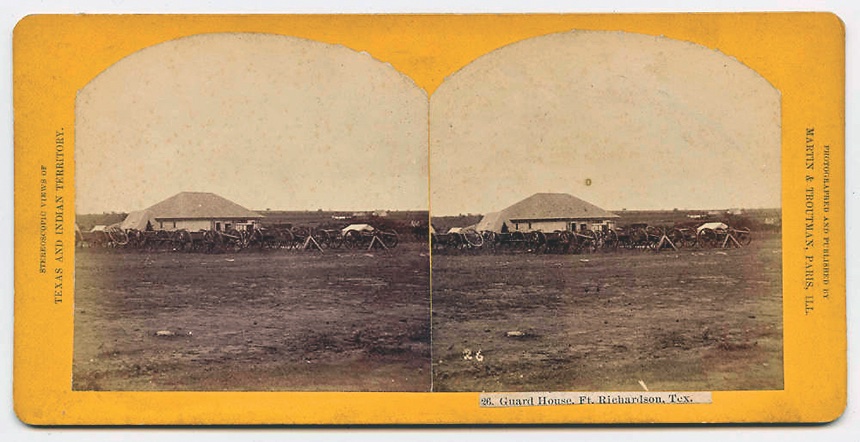

The wagons crossed the Trinity River at Fort Worth (Texas Civil War Museum, Log Cabin Village) and rolled into Weatherford (Doss Heritage and Culture Center), where Warren’s crew joined seven other wagons. Now numbering 12 wagons and 12 men, the train reached Fort Richardson in Jacksboro and continued for Fort Griffin.

What the teamsters had no way of knowing was that a party of Kiowa Indians waited up the trail at Salt Creek Prairie.

All Photos by Johnny D. Boggs Unless Otherwise Noted

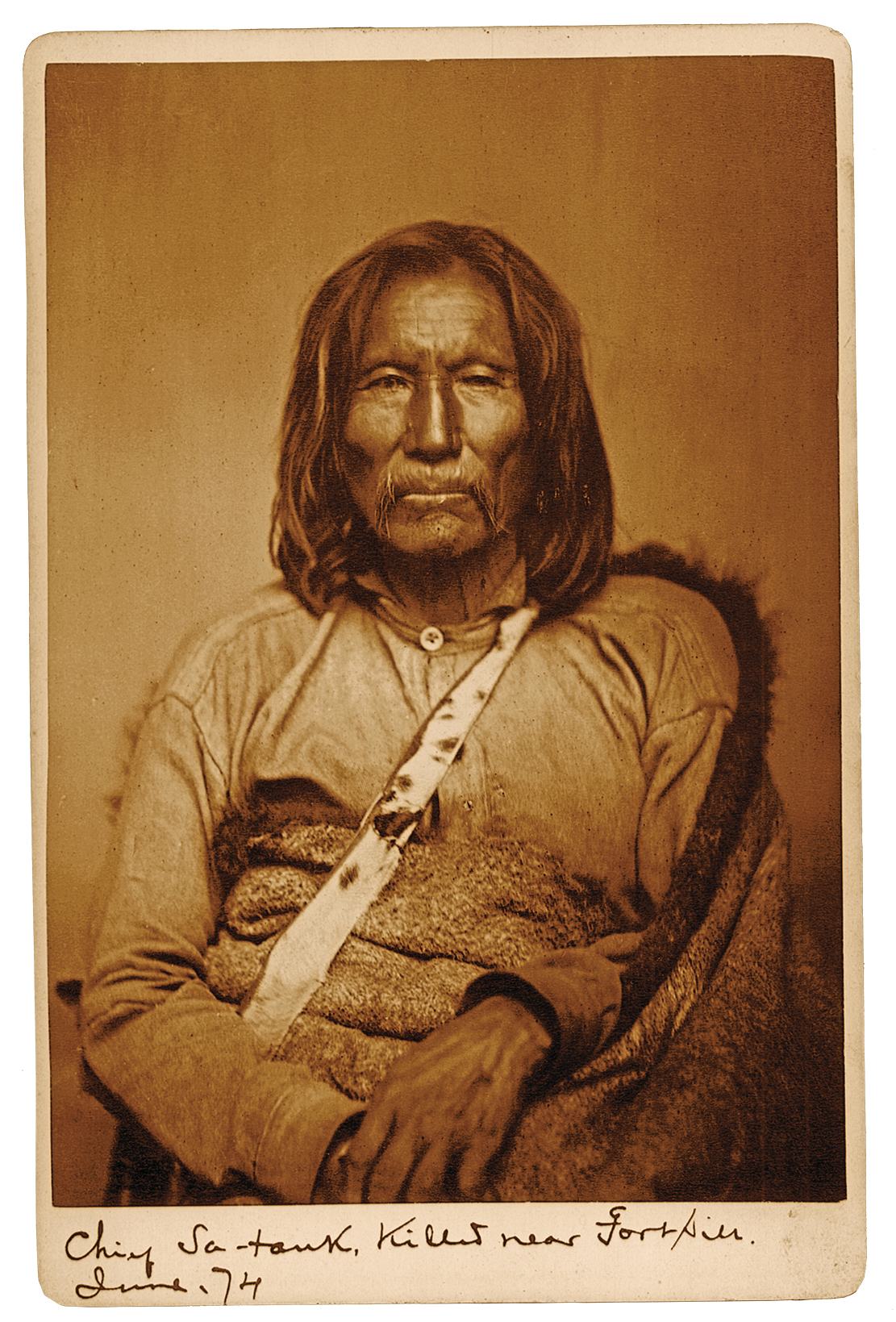

Earlier on the reservation near present-day Lawton, Oklahoma, a prophet and medicine man named Maman-ti had talked an estimated 150 Indians into following him on a raid. Among those joining the prophet were the bragging Satanta, young Big Tree and embittered Satank, who had spoken eloquently at the Medicine Lodge treaty negotiations in 1867 but now carried the bones of a son who had been killed in Texas in 1870.

On May 17, a military ambulance and mounted riders passed the Kiowas. But Maman-ti said his vision forbade attacking. Had the prophet said otherwise, history might have been significantly altered, for in the ambulance rode William T. Sherman, bound for Fort Richardson.

On the next afternoon, Warren’s wagon train came into view, and the Indians attacked. The Kiowas made off with 41 mules and six scalps (seven teamsters had been killed, but one was bald).

Wounded teamster Thomas Brazeal and a colleague walked 20 miles through stormy weather to Fort Richardson. When Sherman heard Brazeal’s story, he ordered Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie in pursuit. Sherman, understanding how close he had come to death, traveled to Fort Sill, intent on bringing the Kiowa leaders to justice.

While the military side of the story is well told at Fort Sill Historic Landmark (the fort remains an active base), the Lawton area is full of places to learn about the Southern Plains culture (Museum of the Great Plains, Comanche National Museum and Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge).

With help from Quaker Indian agent Lawrie Tatum and Col. Benjamin Grierson’s 10th Cavalry, Sherman arrested Satanta, Big Tree and Satank after Satanta admitted taking part in the raid.

William S. Soule, True West Archives

“These three Indians should never go forth again,” Sherman wrote.

Maman-ti, who led the raid, was forgotten.

Mackenzie arrived at Fort Sill on June 4 and, four days later, departed with the three prisoners. Satank, described by an Army and Navy Journal correspondent as “a hoary-headed old sinner sixty years of age or thereabout, grown gray in iniquity and deeds of blood,” covered himself with a blanket, began his death song, slipped free of his manacles, wounded a guard and grabbed a carbine before being shot to death.

On June 15, Mackenzie’s cavalrymen and the two remaining prisoners arrived at Jacksboro, where the trial, presided by Judge Charles Soward, began July 5 in a stifling second-story room at the courthouse. Samuel W.T. Lanham was lead prosecutor. Thomas Ball and Joseph A. Woolfolk were appointed as defense attorneys. Fort Sill’s Horace Jones served as interpreter. Soward allowed the defense motion to sever the trials, and Big Tree was tried first.

Courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife

Courtesy DeGolyer Library, SMU

The Dallas Herald reported that Ball’s “speeches were at some points most eloquent, and displayed…a thorough knowledge of the Indian character.” When Ball asked the jury to let Satanta and Big Tree “fly away as free and unhampered” as an eagle, the defendants grunted and nodded at Jones’s translation.

Ball and Woolfolk called no witnesses for the defense. Lanham labeled Satanta as “the arch fiend of treachery and blood” and Big Tree a “tiger-demon who has tasted blood and loves it as his food….”

It took the jury 30 minutes to come back with a guilty verdict. Court was adjourned.

In his trial the next day, Satanta testified on his own behalf, speaking in Comanche interpreted by Jones. “If you let me live, I feel my ability to control my people,” Satanta said. “If I die it will be like a match put to the prairie. No power can stop it.”

It came as no surprise when the jury found him guilty, too. Both were sentenced to hang in Jacksboro on September 13.

But fearing that Kiowa “match put to the prairie,” Soward pleaded with Gov. Edmund J. Davis to commute the sentences to life imprisonment. Davis agreed, and on October 16, Satanta and Big Tree were transported to the state penitentiary in Huntsville (Texas Prison Museum).

After Satanta and Big Tree were paroled in 1873, Sherman wrote Davis: “I believe Satanta and Big Tree will have their revenge, if they have not already had it, and that if they are to have scalps that yours is the first that should be taken.”

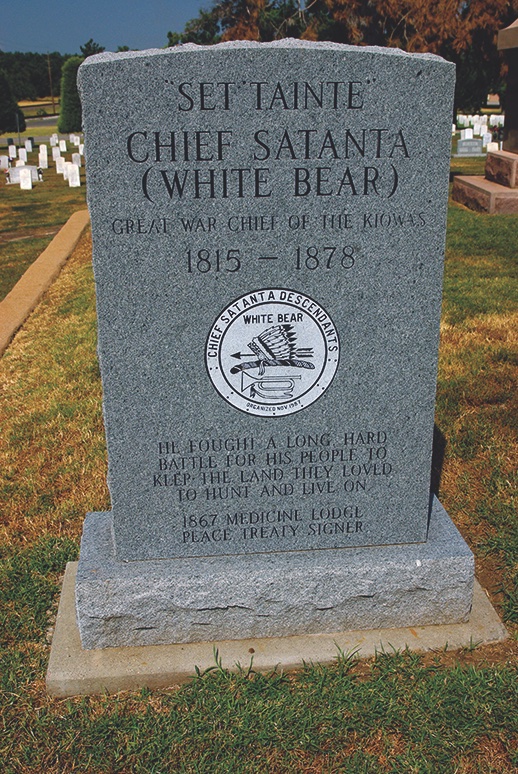

Satanta took part in the Red River War of 1874-75 and was returned to Huntsville, where his health faded. After being told in October 1878 that he had no chance of parole, he slashed himself and was taken to the second-story prison infirmary. Left alone, he committed suicide by jumping from the landing.

Texas papers weren’t sorry to learn of the suicide. Calling Satanta “the Indian monster,” The Galveston Daily News said, “Satanta was long a name on the plains to hate and abhor.”

Big Tree, however, worked on a supply train after his parole, helped establish the Rainy Mountain Indian Mission and joined the church in 1897, serving as a deacon until his death in 1929.

In 1963, Satanta’s grandson asked Texas Governor John Connally for the Kiowa leader’s bones to be returned home. It wasn’t easy, but a resolution passed, and Satanta’s remains were reburied with honors at Fort Sill.

“Satanta,” historian Charles Robinson wrote, “was going home at last.”

Johnny D. Boggs won a Western Heritage Wrangler Award for his 2003 novel Spark on the Prairie: The Trial of the Kiowa Chiefs.

A Wide Spot in the Road

City Greenwood Cemetery

Larry McMurty’s death earlier this year likely sent many fans back to Lonesome Dove, where they could shed tears over Call’s journey back to Texas to bury his old friend Gus. The character that inspired Gus was cattleman Oliver Loving, who is buried at the City Greenwood Cemetery at 300 Front Street in Weatherford, Texas. The cemetery was formally established in 1863, though the land, known as “the Burial Grounds,” was used to inter the dead much earlier (the oldest grave is dated 1859). By 1877, the cemetery was considered “sadly neglected,” but restoration began in the 1980s. Loving isn’t the only notable figure among the estimated 1,000 graves. Trail driver Boze Ikard, upon whom McMurtry drew upon for the character of Deets, rests here, as does Civil War Medal of Honor winner Chester Cowen and Gov. Samuel W.T. Lanham, who prosecuted the Kiowas in the Jacksboro trial. WeatherfordTX.gov

Good Eats and Sleeps

Good Grub: Meers Store and Restaurant, Meers, OK; Our Place Restaurant, Mansfield, TX; Herd’s Hamburgers, Jacksboro, TX; 1836 Steakhouse, Huntsville, TX

Good Lodging: Plantation Inn, Medicine Park, OK; Angel’s Nest Bed & Breakfast, Weatherford, TX;

The Purple Thistle, Jacksboro, TX; Stockyards Hotel, Fort Worth, TX