— M. Forsberg, Courtesy Nebraska Tourism —

Indian removal doesn’t get the coverage of Indian conflict. To wit, Google searches on “Ponca” netted 5.2 million hits, compared with 239 million for “Sioux” and 204 million for “Cherokee.” “Crazy Horse” garnered 20.6 million hits, and “Trail of Tears” got more than 7.7 million. But “Standing Bear” totaled only 609,000.

That’s a shame because the forced removal of the Ponca Indians from their northern Nebraska homeland ranks among the most tragic. After all, white man’s greed led to the expulsion of the Cherokees from the Southeast. But the Ponca people lost their land to, at best, a clerical error. And while fighting Indian leaders like Crazy Horse deserve all the respect they can get, Standing Bear fought a battle, too, except in a courtroom—and his victory was important for every American Indian. Standing Bear et al v. Crook also led to the formation of organizations (Women’s National Indian Association, Indian Rights Association and others) and the beginnings of pro-Indian movements that are still fighting for Indian rights nationwide in 2019.

“I see Standing Bear as the catalyst for this late 19th-century Indian reform movement,” says Spur Award-winning historian Val Mathes, co-author, with Richard Lowitt, of The Standing Bear Controversy: Prelude to Indian Reform.

But Standing Bear still doesn’t get enough attention.

The Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs seeks to change that as it works to achieve designation of a national Chief Standing Bear Trail that would lead from Standing Bear’s Nebraska homeland, through Kansas and into Oklahoma (ChiefStandingBear.org provides background, history and an interactive trail map).

Tragedy begins

— True West Archives —

The Poncas’ Trail of Tears had its beginnings with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, in what authors Ronald C. Naugle, John J. Montag and James C. Olson call in History of Nebraska, “the Poncas’ greatest tragedy.” By honest mistake or “dastardly deception,” the Ponca reservation north of the Niobrara River in present-day Nebraska was included in the Great Sioux Reservation.

Mistake or not, the Department of the Interior made no effort to correct the error, and on May 16, 1877, the first group of Poncas set out, on foot, for the northeastern corner of Oklahoma. The first child died four days later.

You can start your journey today in Niobrara, where the Ponca Tribal Museum and Library displays photographs and historical items—including headdresses, carvings and beadwork, much of it repatriated from Washington’s Smithsonian Museum in 1999.

Storms plagued the Poncas on their march south and east. Another child died on May 23. By May 29, they reached Columbus (Platte County Museum) and rested a few days. On June 5, near Milford, Standing Bear’s daughter, Prairie Flower, died and was buried, possibly in the Mt. Pleasant Cemetery or perhaps in Milford.

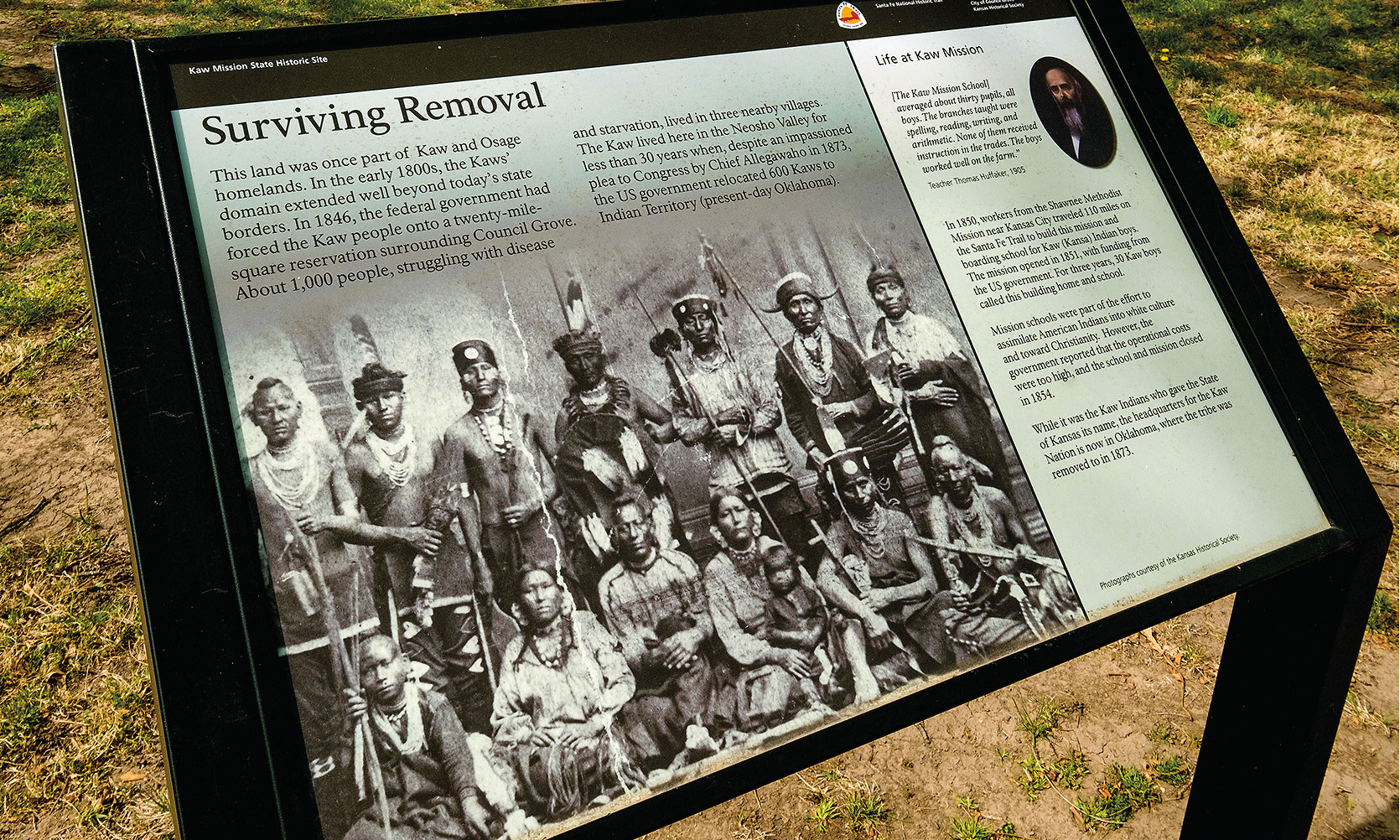

The following evening, a tornado injured many Poncas. Worse, Standing Bear’s granddaughter died on June 8 and was reportedly returned to Milford for burial. They kept moving south and east, through Beatrice and into Kansas—Marysville (Pony Express Barn), Manhattan (Riley County Historical Museum), Council Grove (Kaw Mission State Historic Site), Emporia (Red Rocks State Historic Site)—before reaching their new home three miles south of Baxter Springs, Kansas (Baxter Springs Heritage Museum), near Quapaw, Oklahoma, on July 11. Nine Poncas, including six children, had died.

When Oklahoma wasn’t OK

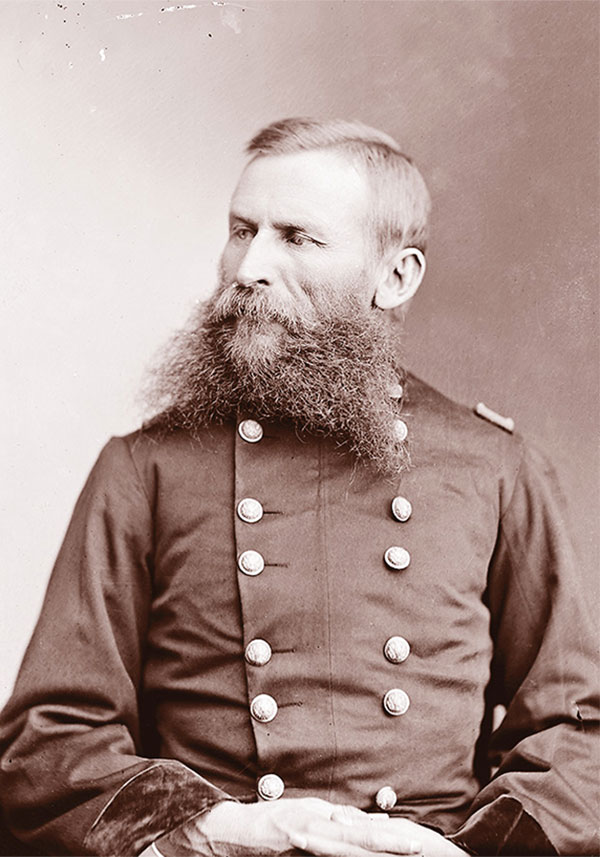

— George Crook Photo Courtesy Library of Congress —

Things worsened; disease killed 158 by the new year. In the winter of 1878, Standing Bear’s dying son, Bear Shield, asked to be buried on the Niobrara. Like most fathers, Standing Bear wasn’t one to deny his son’s last request.

On January 2, 1879, Standing Bear led 27 Indians for their home country. In late February, Omaha Indian leaders brought the refugees into their reservation. The secretary of the interior ordered the arrest and return of the Poncas, a job that fell to Gen. George Crook. The Poncas surrendered and were brought to Fort Omaha.

And history took a giant step forward.

— True West Archives —

“If we can do something for which good men will remember us when we’re gone, that’s the best legacy we can leave,” Crook reportedly told Thomas Henry Tibbles, the Omaha Daily Herald’s deputy editor, who recorded his memoir, Buckskin and Blanket Days, in 1905.

Tibbles found two attorneys, John Lee Webster and Andrew Jackson Poppleton, who were intrigued at the possibility of using the 14th Amendment to protect an Indian’s rights. With Crook’s consent, the attorneys filed a writ of habeas corpus—making the general out as the bad guy—on April 8.

Trial of the century

At the old fort grounds, now the Metropolitan Community College campus, the General Crook House Museum and the neighboring Douglas County Historical Society, offer excellent looks at Crook and the Standing Bear case.

— Courtesy Nebraska Tourism —

That case went before Judge Elmer Scipio Dundy on May 1-2, 1879, and ended when Dundy allowed Standing Bear to address the court. Using an Omaha Indian woman, Suzette LaFlesche (aka Bright Eyes), as his interpreter, Standing Bear told the judge: “The same God made us both.”

— Courtesy Kansas Tourism —

On May 12, Dundy issued his ruling that “an Indian is a PERSON” and that “Indians have the inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

An appeal was filed, but the Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

Pros and cons

The ruling proved costly, however, for the Poncas. “Because of the decision,” Mathes says, “…Standing Bear and those who had accompanied him and his wife on their flight from the Indian Territory to their former Nebraska homeland were now homeless.”

— Photo of Standing Bear Museum Courtesy TravelOk.com —

Eventually, the Poncas split into two tribes: The Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma, based in Ponca City—where Oreland C. Joe’s 22-foot bronze statue of Standing Bear dominates the Standing Bear Museum and Education Center—and the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska.

– Courtesy TravelOK.com –

Standing Bear died in 1908 and was buried in his homeland.

“To me, personally, the most important result of Standing Bear was the involvement of Helen Hunt Jackson in Indian reform,” Mathes says. “Jackson attended one of his lectures in the fall of 1879. His description of the hardships his Ponca tribe endured during their removal to the Indian Territory in 1877 so troubled Jackson that she spent the final six years of her life researching and writing about the government’s treatment of all tribes. Her A Century of Dishonor presented the history of seven tribes, including the Poncas.”

Johnny D. Boggs recommends the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha and the Missouri National Recreational River near Niobrara.