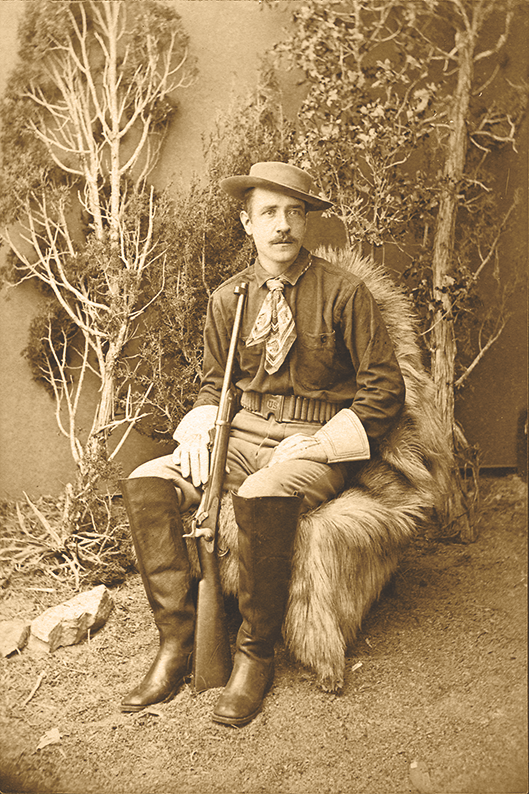

Despite the prominence of repeating rifles of the late 19th century, the U.S. Cavalry largely relied on this single-shot carbine to bring an end to the Indian Wars.

The U.S. Army of the 19th-century West faced challenges that made frontier warfare unique. Vast open plains, seemingly never-ending deserts and rugged mountainous terrain made movements slow and resupply difficult. The Army chased an elusive enemy that was fighting for their homeland by waging guerilla warfare. Because a mobile mounted force was required to keep after the fast-moving, phantom-like Indians, much of the work fell to the cavalry, whose primary weapon was the 1873 Springfield “trapdoor” carbine.

Created in 1873 for the new .45-70 Government round, the single-shot Springfield was produced by the Springfield Armory in Springfield, Massachusetts. Basically the same in appearance and action, the carbine and longer rifle were constantly going through subtle changes. A review of just the carbine variations here would require too much space. Suffice it to say that despite the 1886 Experimental carbine and the Officer’s Model Rifles, the 1873, 1877, 1879 and 1884 Carbines (official government model designations), were the primary issue arm of the U.S. Cavalry during the campaigns against the American Indian tribes.

All Images Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection Unless Otherwise Noted

The side hammer Springfield .45-70 carbine weighed a light seven pounds and was 41.3 inches in length with a 22-inch round barrel. The rifle fired the powerful .45-70 Government cartridge using a 405-grain lead bullet, and 70 grains of musket-grade black powder. The cavalry carbine usually used a lighter 55-grain powder charge because horse soldiers tended to be small of stature, usually weighing around 130 to 150 pounds, and the stiff recoil from the heavier rifle load too often proved detrimental to the trooper’s accuracy.

The .45-70 proved to be a more accurate and powerful load for longer range shooting than the previous .50-70 round. After the disastrous Little Big Horn fight in 1876, the carbine was much maligned, however history has shown that tactics notwithstanding, what was then considered the fault of the weapon itself was actually more of a problem with the brittle copper cartridges, despite some other less critical weaknesses in the initial 1873 Springfield’s design.

The 1877—a transitional model upgraded from the first 1873 Spring-field—produced the most visible im-provements over the original carbine. Changes included lengthening the comb of the stock and shortening and thickening the stock’s wrist, while also stiffening the breechblock by filling in the high arch of the earlier arm. Other significant changes consisted of an improved rear sight, and drilling the butt stock with a three-hole receptacle for the three-piece jointed steel ramrod and headless shell extractor. A swiveling cover on the butt plate, over the drilled holes was also added, thus the modern “Trapdoor” moniker. A three-notch carbine “Safety Notch” tumbler lock mechanism, the three-click hammer, was added, and the “1873” date was omitted from the lock plate.

The 1879 modifications included an improved rear sight employing a “buckhorn” eyepiece attached to the slide, which can be moved laterally for wind, drift or any construction errors in the carbine (and rifle). The stacking swivel on the carbine’s barrel band was also eliminated. The 1884 model differs from earlier carbines mostly with the addition of the Model 1884 Buffington Rear Sight and the change of the breech block stamping to “US MODEL 1884.” By 1886, the firing pin was changed from steel to an aluminum bronze alloy, and in 1890 a “Rear Sight Protector Barrel Band” and a “Front Sight Cover” were added. Manufacturing of this final model ceased in 1889.

With nearly 61,000 carbines produced, in the hands of regular Army troopers, the 1873 Springfield carbine—regardless of which variation—played a critical part in the frontier. During much of the Indian Wars, it was largely this carbine in the hands of troopers throughout the West who fought countless battles, rode endless patrols and did scouting duty. Ironically, after vanquishing the American Indians to reservations, the Army worked to protect them from unscrupulous settlers. There’s no doubt that the 1873 Springfield carbine belongs in that vaunted listing of the guns that truly “Won the West.”

.45-70 Springfield Collectors Book

Long considered the last word by serious students of .45-70 “Trapdoor” Springfields, the book For Collectors Only, The .45-70 Springfield ($34.95) by respected arms historians Joe Poyer and Craig Riesch, is in reprint. Like the other works in their “For Collectors Only” series, this 315-page, 5½-inch by 8½-inch softcover volume contains a part-by-part analysis of the various models, including serial number ranges, markings, finishes and other details. Trapdoor fans will find this book an indispensable aid in identifying the vintage of any .45-70 Trapdoor Springfield rifle, carbine, Officer’s and Experimental models—even Fencing Muskets, no matter how subtle any changes of component parts are found. Also covered in this edition are tools, cartridge boxes and Prairie Belts, ammunition, bayonets and more, all shown through clear, detailed photos of parts and related gear. This writer has used the work numerous times and has found it to be invaluable in researching these historic weapons.

northcapepubs.com