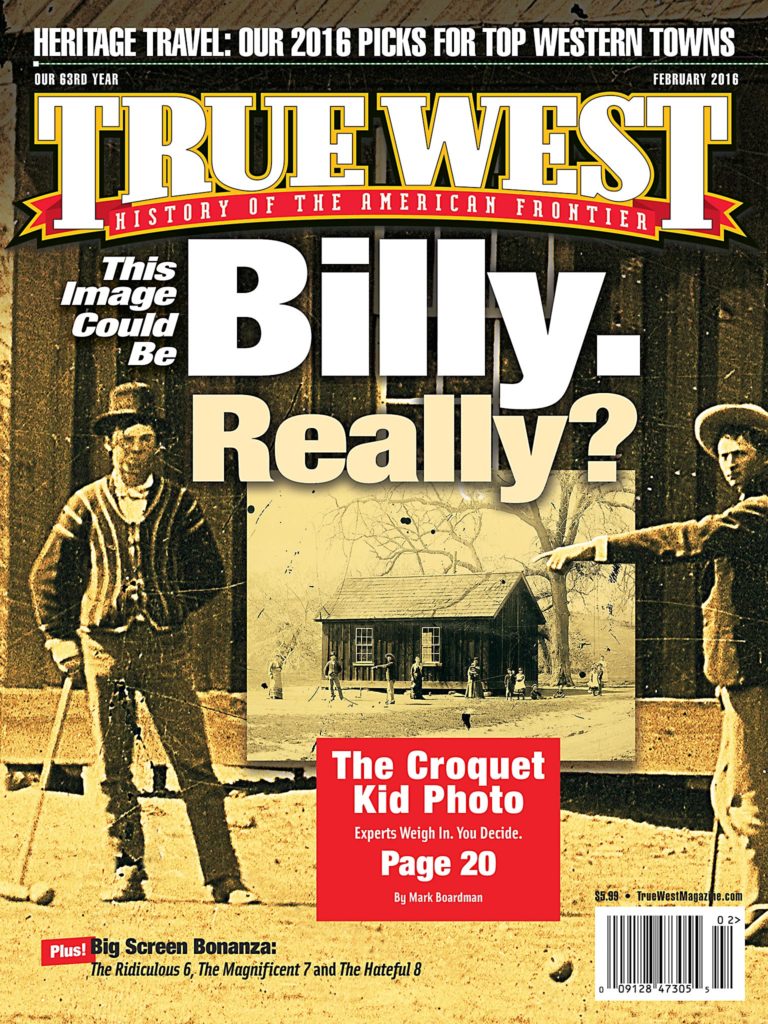

This intriguing photograph may or may not include Billy the Kid, but the real fight is over provenance: the owner and the producers of the TV show claim they have the proof the photo is the real deal. Others disagree. We gathered all the pros and cons and all the facts we could find. Have fun.

– Courtesy Randy Guijarro –

An earthquake hit the Old West field in the fall of 2015. And a staid, relatively genial and, for the most part, collegial area of study was dragged into the mud of modernity—because of a four-inch-by-five-inch piece of tin that may contain a picture of Billy the Kid.

The photo was the subject of a National Geographic Channel show that premiered on October 19, 2015. But even before it aired, people associated with the show told True West they had proved and authenticated that the tintype was the real McCoy. We were excited by the possibility. Who wouldn’t want to have another photograph of one of the West’s most famous outlaws?

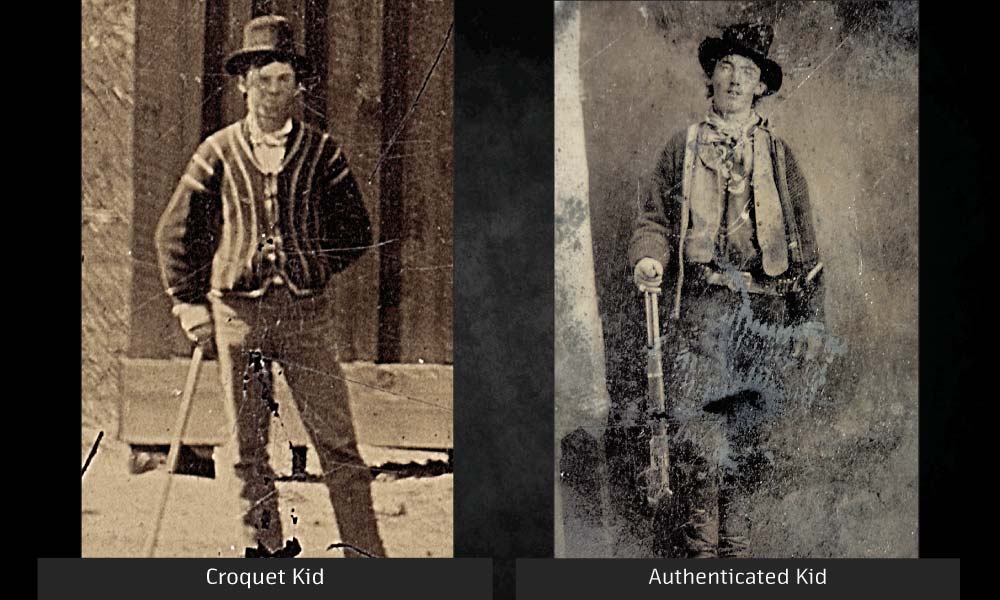

The only authenticated photograph of the Kid has already proven its value, having sold in 2011 at Brian Lebel’s Old West Auction for $2.3 million. With stakes high on the possibility of a new Kid photograph, True West turned to trusted advisors who know the history well, instead of relying just on the perspectives presented in the show. Our only agenda is the truth. The owner of the tintype, however, is anticipating a $5 million payday.

When experts in the Old West field shared their opinions of the tintype, the show’s producers took the critics to task. Criticism in the Old West field is normal. It scrutinizes evidence or quotes or conclusions—the work, the publication, the production. The debate over the Croquet Kid tintype struck a chord immediately among history aficionados. Then outsiders went after what they viewed as the “old guard” establishment. The two sides engaged in a social media bloodbath. Charges and countercharges. Personal and professional insults. Public postings of personal information. Challenges to fistfights. I was even threatened with a lawsuit. For many folks—me included—the conversation was disconcerting, disgusting, demeaning and a bit depressing.

Let’s be clear here: the “old guard” label is inaccurate. Many of these historians have spent their lives searching for truths hidden in often hard-to-find primary accounts, all the while reinvestigating established facts that may have resulted from misguided research. In fact, one of the experts, Frederick Nolan, just published last year new research on the Kid, questioning his own earlier understanding of historical reports (read The Birth of an Outlaw).

To get away from all the insults and threats that distract from the conversations people are having to determine the historical validity of this tintype, True West presents the history behind the tintype, the questions raised about the show’s findings and the latest provenance news presented on the tintype, so you can decide for yourself if the Croquet Kid is Billy the Kid.

Young Guns

The story begins in 2010. Randy Guijarro found some tintypes in a flea market in Fresno, California, which he purchased for $2. He thought a man in one of the photos looked familiar—like Billy the Kid. The Kid figure was holding a croquet mallet, standing in front of a building, accompanied by several other men, women and children. The more Guijarro looked at the photo, the more convinced he became—this was the Kid.

He brought the tintype to experts in the Old West field—including photograph collectors and researchers John Boessenecker and Robert G. McCubbin. (Disclosure: Boessenecker is a contributing editor to True West and McCubbin is the magazine’s publisher emeritus.) Their assessments: the man did not look like the Kid; the image had no provenance tying the image to the Kid; no proof supports the notion that the tintype was taken in New Mexico around 1878.

But Guijarro was not convinced by the naysayers. In fact, he resented being dismissed so quickly and, in his mind, so casually. He kept showing the tintype around, and word of it reached acknowledged Billy the Kid scholars Frederick Nolan, Robert Utley, Paul Hutton and Drew Gomber, as well as noted Western Americana appraisers and auctioneers Wes Cowan, Brian Lebel (who appears in the show) and Tim Gordon. None supported Guijarro’s claim. Guijarro dismissed them as “so-called experts.”

Determined to Succeed

By October 2014, Guijarro had met producer Jeff Aiello of 18THIRTY Entertainment at a collectibles store in Clovis, California. Aiello produces primarily commercials and reality shows, and he was intrigued by Guijarro’s story of the tintype.

Aiello and his wife began researching the Lincoln County War, Billy the Kid and the Regulators, and both became convinced that the photo was of the Kid.

By December, Aiello had hooked up with Steve Sederwall, a controversial ex-lawman in Lincoln County (see The Lunacy of Billy the Kid, published in True West’s July 2010 issue). Sederwall signed on as the investigator researching the location where the tintype could have been taken. Early in 2015, Leftfield Productions agreed to coproduce the show and then sold the show to the National Geographic Channel, which convinced actor Kevin Costner to join the project as executive producer and narrator.

In June 2015, forensic scientist Kent Gibson came aboard as the facial recognition expert. Appraiser and auctioneer Don Kagin, primarily known for coin collections, joined in September to authenticate the tintype. The show aired in mid-October.

Case for the Croquet Kid

What follows is a breakdown of the show’s major claims. First, the tintype was taken at Charlie and Manuela Bowdre’s wedding celebration in the month or so after the July 15-19, 1878, battle in Lincoln, New Mexico—the largest armed battle of the Lincoln County War. The war had begun after the murder of rancher John Tunstall on February 18, a competitor of mercantilers Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan. The Regulators were supporters of Tunstall’s and included Charlie Bowdre and Henry McCarty, who later became famous as Billy the Kid. The Regulators lost at least five men in the July battle; the remaining Regulators escaped and disbanded, and the civilian conflict officially ended.

Second, the photograph was taken near a schoolhouse on the ranch owned by the Regulators’ deceased boss, Tunstall, situated along the Rio Feliz, some 30 miles south of Lincoln.

Third, in addition to the Kid and the Bowdres, Paulita Maxwell, Sallie Chisum—the niece of cattle baron John Chisum, an ally of Tunstall’s business partner Alexander McSween—and Regulators Tom Folliard and “Big Jim” French are in the picture, along with some unidentified folks.

The show tells the story of a treasure hunt, a reality show quest by Guijarro and his wife to find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, to authenticate a rare piece of history and to make a small fortune. Re-enactments provided historical reference, although most were not that accurate, which producer Aiello admits. For instance, Tunstall was shot and killed while on foot (he was actually killed on horseback). As of press date, you can still watch the National Geographic Channel show and related videos on Aiello’s Vimeo page.

The old guard did not buy into the show’s claims. Many announced that they would welcome the discovery of a new Billy the Kid photograph—but they had a lot of questions that needed to be answered before accepting this one as authentic. What are those questions? Let’s take a look to see why the show that convinced 59 percent of our audience has left some people still on the fence.

Proof of History

The biggest questions have centered on certain items in the tintype that the show did not fully explain.

- Croquet? In the Wild West?

Actually, this tintype could very well be an authentic historical image of folks playing croquet out West in the late 1800s. Croquet was a popular sport in the U.S. in the 1870s—including in the Southwest. Croquet sets were being sold at Frank Chapman’s store in Las Vegas, New Mexico, according to an advertisement published in the June 22, 1878, Las Vegas Gazette, provided to True West by Sederwall.

- If the tintype was taken in late July or in August (or even in September, as the producers now claim), why is the tree leafless and the ground bare of leaves? And why are the people wearing sweaters and overcoats when summer months in New Mexico offered the highest temperatures of the year, averaging a range from the 80s to 50s?

Kagin, the auctioneer who appraised the tintype’s value as $5 million, offered an explanation for the leafless trees: a drought impacted the plants at the time the tintype was taken. Actually, history records a break in the drought that year and that the area got a higher than normal amount of precipitation. Just above the croquet set advertisement for Chapman’s store in Las Vegas on June 22, 1878, is a news alert: “The rainy season seems to have fairly set in.

- How does the story tying the building in the tintype to John Tunstall’s ranch jibe with history?

Everyone agrees the current building found on the property—the Flying H School—dates to the 1930s, but the show argued that another building, a school, was constructed on the Tunstall ranch site in the early to mid-1870s. The Casey family owned that property along Rio Feliz at that time, yet no evidence proves the Caseys built a school. Patriarch Robert Casey built a dugout home on the property.

The Casey kids were educated at Casey’s main ranch, along the Rio Hondo, daughter Lily Casey Klasner remembers in her autobiography. But all of the ranch buildings at that time, including the family home that housed the informal school, were constructed out of adobe, not wood. When the home was later converted into a store, around 1872, the Casey family had a wooden door put on it, a luxury item in an area where lumber was scarce.

Tunstall took over the Rio Feliz property in 1876, a year after Robert Casey was murdered. Tunstall wouldn’t have needed to build a school—he had no kids and neither did most of his ranchers (who became the Regulators). The place was in limbo after Tunstall was murdered in 1878; the Casey family tried to get back the property, but never relocated to the site.

The show’s identification of the building as the Felix School is inaccurate, researchers Dan Buck and Phil King report. The original school opened on the property sometime between mid-1898 and December 1901, and closed in 1934, noted Ernestine Chesser Williams, in Chaves County Schools, 1881-1968. She included a photo of the school in 1925, which had clapboard siding (horizontal) and a two-over-two double-hung window, completely different features than the schoolhouse in the tintype, which had board-and-batten siding (vertical) and six-over-six doubly-hung windows.

An 1883 government survey of the area—including this specific township—lists no structure (or ruins) on the property. The survey is thorough; it even mentions a tent. Experts believe that the more likely scenario is Dolan, who took over the land in 1880, constructed the building in the 1890s, when numerous children lived on the property.

- Could a case be made for a wooden building in New Mexico Territory in 1878 where the Kid possibly could have visited?

The 1883 survey notes the lack of timber in the area, that the soil was rocky and barren—whereas the Croquet Kid tintype portrays plenty of trees, which the show speculates are orchards, and a prominent wooden building.

Robert Casey built a dugout, a combination of rock, adobe and wood, not a wooden building, on the Rio Feliz site that the show identified as the location in the tintype. Tunstall built an adobe and log home on the site, probably in late 1877. The 1883 survey makes no note of the Felix School, or any school, that the show claims is the building.

What if we cast the net a bit wider, to the main Casey ranch? Lily noted the property had “few trees.” She pointed out that the pine roof of the family’s adobe home was so unusual since they were in a “country where lumber was…scarce.” The trees that were on the property: a grove of pecans the Caseys planted and willows that grew along the Rio Hondo; the pine was not local, as it came from the mountains, making it expensive and rare as it had to be imported.

Could the trees be the pecans on the main ranch? If the family planted those in 1867 or 1868, soon after they arrived, the trees would have been 12- to 18-feet tall at most in 1878, much shorter than the trees in the tintype. Even more, Lily stated that “some foolish boy” had cut down a “good many of them,” which may explain why the 1883 survey did not identify pecans in the area.

Even if the pecan or willow trees were around on this property in 1878, this lumber would not have been used to construct a wooden building, since both are hardwoods, usually good for furniture, while softwoods are used for buildings. That an entire building, not just the roof, would have been constructed out of wood in this part of New Mexico Territory is highly unlikely.

If pioneer ranchers did get the money and materials to build an entire wooden building on either property, or anywhere in the area, then the 1883 survey would have noted such a rare structure.

- The show claimed that the hills in the tintype match the hills of the Flying H School site. Locals and historians disagree, stating the hills and terrain behind the building do not match current configurations of the Tunstall ranch site as shown in modern photographs.

- How do we know that the man believed to be the Kid is five feet and eight inches tall, the Kid’s height?

In the show, facial recognition expert Kent Gibson says he extrapolated the height of the young man holding the croquet mallet by the mallet’s standard length of 36 inches. But mallets at that time ranged in lengths from 24 inches to 40 inches, so no standard length existed. Guessing the length of the mallet to coincide with the height you want the man holding it to be is not good science.

- How can the man pointing to the Kid be identified as Tom Folliard (the show incorrectly calls him O’Folliard)?

In the tintype, these two men appear to be about the same size. But contemporaneous descriptions state Folliard (nicknamed “Bigfoot”) was more than six feet tall and 200 pounds—at least four inches taller and 60 pounds heavier than the Kid.

- The show identifies Paulita Maxwell as being in the tintype. In 1878, she was 14 years old, and her brother Pete was protective of her. Would he have allowed her to travel 120 miles from Fort Sumner to the Tunstall ranch for such a party? Proponents believe he did.

- If your own expert couldn’t prove his claim in a court of law, how can his claim be worth anything?

In the show, Gibson states he used facial recognition technology to compare known photos of Charlie Bowdre, Tom Folliard, Sallie Chisum and Billy the Kid to the figures in the Croquet Kid shot. Gibson concludes the people in the tintype are most likely them. The show later adds others to the list as being “matched” to the tintype: “Big Jim” French, Paulita Maxwell and Manuela Bowdre. But Gibson does not take a definitive position on any identifications: “In a court of law, I would have to deny it. It’s not detailed enough to make it a really valid image.”

- How can the show claim one of the men in the tintype is “Big Jim” French when we have no known authenticated photographs of French?

- Where are the other Regulators still riding with the Kid—Fred Waite, John Middleton, Henry Brown, Sam Smith, George Bowers, Dirty Steve Stephens, Jose Chavez y Chavez and John Scroggins? Those who disagree point out that these men had not split off from the Regulators at the time of the photograph, and question why they weren’t in the photo too. Proponents state they must not have been invited to the wedding.

- Why aren’t the guys in the tintype armed?

Proponents claim the men in the tintype were carrying guns, but they concealed them. The other side argues that if these guys were on the Tunstall ranch—in enemy territory—they would have had their weapons within reach. History does show that the Kid and the Regulators always carried guns, in holsters, as was the norm for cowboys. The universally accepted photograph of the Kid, the only one known of him to exist, shows him with a pistol on his hip and a rifle in his hand. The only proven photo of Charlie Bowdre—a formal shot taken with his wife—depicts a sitting Charlie with a holstered gun and a Winchester across his lap.

- Were Charlie Bowdre and Manuela Herrera formally married?

The Latter-Day Saints archives has a probate record stating the two may have wed in Fort Sumner, New Mexico, sometime in mid-September of 1878, but no marriage license or records of the wedding have been found. Historian Fred Nolan believes the pair may not have married at all, and hence, would not have had a wedding celebration.

- If history does not record this gathering, how can anyone claim the tintype documents it?

Historians have not found any written or oral record that this gathering, at that time and location, took place. In her diary, Sallie Chisum, the niece of cattle baron John Chisum and the Kid’s friend, recorded her meeting with the Regulators—but that happened in Red River Springs, roughly 40 miles east of Fort Bascom (which is slightly west of the Texas border), not the Tunstall ranch, and it took place around September 25, 1878, not in the weeks after the fight in Lincoln. If this was a tintype of that gathering on Red River Springs, wouldn’t Sallie record in her diary, or a separate journal that she also kept, that a photograph was taken?

Location, Location, Location

Historians have a good idea of the Regulators’ movements during the time in question. From July 20 through September 30, 1878, the boys were on the lam and rustling horses in various places in New Mexico Territory.

After the battle of Lincoln ended on July 19, the Regulators split up, avoiding pursuers. Many reportedly quit the group. Those still in the gang began to reunite three days later, probably at the ranch of fellow Regulator Frank Coe. Over the next couple of months, the Regulators had a revolving cast as some members left temporarily for other obligations—and others quit.

By July 27, gunmen hired by Dolan had gone out, in addition to posses and U.S. Army detachments, to hunt down the Kid and his fellow Regulators.

Things heated up on August 5, when the Kid and friends rustled some horses at the Mescalero Apache Agency—about 40 miles from the Tunstall ranch—and left agency clerk Morris Bernstein dead. (See Mescalero Melee.)

Over the next month, the Regulators traveled all over—Fort Sumner to Anton Chico (for several days), back to Fort Sumner, to Lincoln for a quick raid and back to Fort Sumner, then on to Red River Springs (where they met up with Sallie Chisum and her family) and even left New Mexico Territory and went into Tascosa, Texas. They stole more horses, sold a few of them and watched their gang numbers drop as more Regulators quit. The outfit was pretty well finished by the end of September.

Historians have found no evidence that the gang ever went back to the Tunstall ranch. That was one of the first places their enemies would have looked for them (and Dolan was planning to take over the property). For anyone who believes the Croquet Kid tintype was taken on Tunstall’s ranch, historians question: Would Regulators on the run from the law have taken the time for a celebration in such a dangerous locale?

If this tintype is indeed of the Kid and the Regulators, captured on film after the Battle of Lincoln, then it would have been taken in Fort Sumner or Anton Chico, places where they spent several days (and apparently held some parties). The Tunstall ranch is an unlikely locale.

Moving the Center Post

Since the show first aired, the producers have come up with new theories about the tintype. In football, that is known as moving the goalposts. But since we’re talking croquet, let’s call it moving the center post.

Aiello has teetered back and forth between whether or not the celebration depicted in the tintype was Charlie and Manuela Bowdre’s wedding (or perhaps engagement) party or another type of party. He suggests that whatever the celebration was about, it may have occurred in late August 1878, when Bowdre and fellow Regulator Josiah Gordon “Doc” Scurlock began moving their families from their ranches to Fort Sumner. He has no record supporting that group went to the Tunstall ranch, that they had a party at all or that Sallie Chisum met them. Bowdre and Scurlock moved their families away from danger to a safe haven. Would they have a party at a location where men were out looking for them?

Where does the late August 1878 date come from? The Kid and Regulators spent time with the Chisums for roughly two weeks, definitely from August 13-22 (as reported in Sallie’s diary) and possibly leaving on or around August 24 (as Utley reports). They spent this time at Bosque Grande (Chisum’s original ranch), near Fort Sumner. How does that link them all playing croquet together on the Tunstall ranch?

Aiello tells True West that he puts them on the Tunstall ranch following the Kid and Regulators’ return to Fort Sumner: “At some point, Sallie and Paulita…join the party as they go from Ruidoso [Dowlin’s Mill until mid-1880s], south through the Tunstall ranch to evade the forces of the U.S. Army at Fort Stanton and the sheriff and gangs hunting them in Lincoln.”

At best, this scenario significantly narrows the date for the photograph. Around September 5, the Regulators stole livestock from Charlie Fritz’s ranch on Rio Bonito southeast of Lincoln. This places the likely time for the photograph as September 1 through 4. Even so, the Regulators would have had to go way out of their way, farther south and into enemy territory, for this wedding party. (By then, “Big Jim” French, one of the people identified as being in the tintype, was already in Lincoln guarding Sue McSween.) No evidence supports them making that detour at any time, for any purpose.

To respond to requests for provenance, which is the history that reveals when and where a photograph was taken and who possessed it in the intervening years, Aiello says he has evidence connecting one of Charlie Bowdre’s descendants to Fresno, California, where Guijarro found the tintype. United States Marshals Service Historian David Turk says the great-great-nephew of Charlie Bowdre, Thomas Wyatt Newbern, had the Croquet Kid tintype in a storage unit when he died in Fresno in 1994. If Turk is right and provenance linking the image to the Kid can be proven, that support would change everything (see sidebar by Daniel Buck).

In any case, the folks associated with the show say the Croquet Kid tintype has been authenticated beyond a reasonable doubt, and they have, as Aiello says, “…a level of proof that far exceeds any level needed by most reasonable thinking people, historians or scholars.” Proponents have joined their camp in believing this to be the case.

But several noted historians and scholars still disagree that the Croquet Kid tintype has been authenticated and object to the accusation that they are unreasonable.

The fight for the truth continues. I suspect that when this article appears in mailboxes and newsstands, the arguments will flare up again, continuing this modern Lincoln County War. We hope, at the very least, we have provided the background for you to decide: do you believe the tintype is of Billy the Kid…and, if someone gave you $5 million to buy one piece of Old West memorabilia, would you buy the Croquet Kid?

The Claim

Why do a majority of the people aware of the Croquet Kid image accept its authenticity? Overwhelming evidence, proof and now provenance support the photo.

Facial recognition by one of the top forensic scientists in America, Kent Gibson, who provides his expertise to the U.S. Secret Service and FBI, proved the image contains Billy the Kid, Charles Bowdre, Tom O’Folliard, Sallie Chisum and Paulita Maxwell. Naysayers claim “facial recognition doesn’t work,” but then benefit from its effectiveness everyday in the protection of our nation from terrorists.

Naysayers challenged us to find the location the photograph was taken. We did. We matched the terrain and the structure. So they dug up an old surveying map to prove the surveyor didn’t record the building in the photo. Unfortunately for them, the surveyor didn’t record any buildings on the Feliz River with markings on the map. You don’t try to prove something didn’t exist by trying to demonstrate there is not extant proof of it.

Then from the naysayers: “Show us the provenance.” Discovery of provenance on an image this important is a big deal, which is why we never stopped looking for it. And now, thanks to U.S. Marshals Service Historian David Turk, provenance has been found. The great-great-nephew of Charlie Bowdre, Thomas Wyatt Newbern, had the croquet image in a storage unit when he died in Fresno, California, in 1994.

Additional proof includes expert testimony that the photo was taken between 1876 and 1880; clothing is a period match. Further forensics prove the image was never tampered with.

Statistically, when combining all of the evidence, there is a .062 in billion chance the image contains look-alikes. When you have one person match in a photo, that’s good. But when you match up five people that history records being together in a certain time and place, the odds spiral into probability.

As long as we turn to historians and authors, who also have their own grand collections, for the final say on whether something is “real or not,” there should always be a shadow of doubt cast on their assessments. We should consider their opinions, but not rely on them alone.

—Jeff Aiello, co-executive producer of Billy the Kid: New Evidence

Dueling Quotes: Experts Face Off

“The truth does not matter—and I can’t figure out why.”

—Randy Guijarro tintype owner, in Billy the Kid: New Evidence

“…the written record corroborates the case that the people believed to be in this image were indeed all together for two weeks in New Mexico Territory in 1878. To have one person of a known group of close associates score a high-level match with facial recognition technology is one thing, but to have five of those individuals also match in a photo proven to be undoctored or altered is overwhelming…the odds of probability that this photograph is a reliable source and is indeed of Billy the Kid and the Regulators is about a close as you can get to certain.”

—Darren A. Raspa chair of the Western History Association’s Graduate Student Council and PhD candidate at the Department of History at the University of New Mexico

“I’ve been taking wet-plate tintypes in the field now for 25 years. I’ve studied thousands of images of cowboys from the 19th century. The croquet tintype is dead-on for 1878, and the clothing is correct for New Mexico in 1878.”

—Will Dunniway wet-plate collodion photographer and photograph historian

“To me physical posturing and positioning is almost as unique to an individual as their facial features. Charlie Bowdre has the same head tilt and posture in both his cabinet card with Manuela and Randy’s image. Billy has the same stance in the iconic image as in Randy’s…. Paulita Maxwell and Sallie Chisum have postures that match their postures in their other known photographs. Paulita Maxwell’s shoulders come forward slightly, and Sallie Chisum has almost perfect spinal and shoulder alignment.”

—Whitney Braun PhD, MPH, Masters Human Bioethics at Loma Linda University

“This is simply another of the long chain of want-it-to-be-the-Kid pictures. This one poses even less credibility than its predecessors. We so-called experts have been showered with a flood of Billy pictures that their owners were sure were Billy because they looked like Billy.”

—Robert Utley author of Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life

“Regardless of what is said by paid ‘experts,’ their conclusions are conjecture, not fact. No matter how sophisticated the hype that accompanies them, it’s still hype and nothing else. The ‘proof’ they offer is nothing more than wishful thinking, and the historical value of the image is zero.”

—Frederick Nolan author of The West of Billy the Kid

“I wish Randy and Linda only the best, and am pleased with the exposure our event in Fort Worth, Texas, received in the film. However, I do not believe that the program should be called a documentary. It is masterfully edited reality television, produced to entertain, not inform. For example, the film is edited to give the impression that the first time I saw Randy’s photo was in Fort Worth in June 2015, when he had shown it to me several years prior at a show in California. That the Croquet Kid photo had been known to many of us in the industry for a number of years is never mentioned, but rather creative editing gives the viewer the impression that Randy’s quest happens over a whirlwind four-month period (the time between the Fort Worth show and the airing of the program).

This is simply not true.”

—Brian Lebel auctioneer who sold the authenticated Billy the Kid tintype

“Well, I could have missed something. Surely Sallie made an entry for September 1878 that reads: ‘Played croquet at the Bowdre wedding. William Bonny [sic] is a sore loser. Oddly, all the trees have lost their leaves.’”

—Billy the Kid author Mark Lee Gardner being tongue-in-cheek about Sallie Chisum not including the wedding in her diary

Chain of Custody to Bowdre and New Mexico?

The advantage I bring to the question of the croquet tintype is that I know very little about the Lincoln County War, and I’m a noncombatant in the modern version.

When I initially looked at the croquet-mallet armed young man in the tintype who is supposed to be Billy the Kid and compared him to the accepted genuine tintype image, my blink reaction was no, not Billy. He looked more like Alfalfa of Our Gang.

I did keep the door ajar, though, because sometimes the same person appears dissimilar in different photographs. On the other hand, some people look alike, so you can have two distinct people who look similar. Possible celebrity-outlaw photographs can be confounding.

My real question was, where did the tintype come from? What’s the link to Billy the Kid? Provenance can be as simple as geographic origin, where something was found, or as complicated as a long chain of custody, with or without missing links, back to the original owner or maker. Initially, the proponents of the Croquet Kid tintype had no useful origin story, save that it had been purchased in Fresno, California, in 2010 by Randy Guijarro, out of what he described as a box of “Fresno photos,” from a couple of fellows who had cleaned out a storage unit.

Instead of researching the tintype’s origins, Guijarro and the television team reverse-engineered the tintype, first concluding that it depicted Billy the Kid and colleagues, and then moving backwards looking for ways that would be so. Not only was the cart before the horse, the horse was nowhere to be seen.

Only after the show had aired last October, and the proponents had suffered a great deal of criticism, did they find some useful information, that the tintype might have come from the personal effects of Thomas Wyatt Newbern, the great-grandson of Benjamin Bowdre, who was one of Charles Bowdre’s several brothers. Newbern had lived in Fresno and died there in 1994, and some of his belongings from his storage unit had later been sold. Excellent. The last owner in the Bowdre chain was the great-great-nephew of Charlie Bowdre, who is supposedly one of the men in the tintype. But wait, the provenance presumably leads back to Benjamin, who lived and died in Mississippi and never knew Billy the Kid.

Whistle in Occam’s razor. Would it not be prudent to explore the Benjamin link? A simple and reasonable answer might be that the image depicts Benjamin, his family, and friends. The tintype proponents, whose motto seems to be, “when you hear hoofbeats, think Billy, not horses,” were not interested. In fact, even before establishing any serious origin story at all, Jeff Aiello, a producer of the National Geographic Channel show and a vocal proponent of the tintype’s Billyness, had declared on his Facebook page that its authenticity was “supported by an amount of evidence that would convict a man for murder if this were a court case.”

Maybe convict an innocent man. During the show, Kent Gibson, the team’s forensic facial recognition expert, after his computer had for reasons that were not clear made an 80.1 percent match between two seriously murky, hat-draped faces, said that if called to testify in court, he would “deny” there was a match.

Cart before horse had also led the tintype’s advocates to argue that because the Kid is in the image, and because there is what appears to be a schoolhouse behind him and because there was a schoolhouse on the ranch of his friend John H. Tunstall, both must be the same schoolhouse and therefore the man in the image must be the Kid. When I read that line of reasoning, two questions hit me. Was there a schoolhouse on the old Tunstall ranch? And, more important, when was it built?

Georgia researcher Eddie Lanham, whom I met on B.J.’s Tombstone History Discussion Forum, provided a key document. We initially determined that not one, but two schoolhouses had been built in the upper Felix Valley in southern New Mexico, near the Tunstall ranch. The key document: The older Felix School was not on an 1884 survey map that Lanham dug out of a Bureau of Land Management archive. Nor was it on an 1898 Roswell Record list of Chaves County schools. The second school—called the Flying H—was built in 1935, meaning that both schools postdated Billy the Kid’s death in July 1881. The calendar is the researcher’s best friend. Finally, a photograph of the older Felix School, built circa 1898, was found by researcher Phil King in Ernestine Chesser Williams’s Chaves County Schools, 1881-1968. It’s not the schoolhouse in the croquet tintype.

Without any link to New Mexico, the only provenance the Croquet Kid tintype has is that it might once have belonged to the great-nephew of the brother of a friend of Billy the Kid’s. Certainly better provenance than a Fresno storage unit, but not in my view sufficient, given the reservations historians have about who is in the tintype, and especially given the $5 million dollar asking price.

—Daniel Buck

The Man who Gave the Kid to the world

Despite the gift he gave to Old West historians, Dan Dedrick does not even warrant his own Wikipedia page, a sure sign of a forgotten person in modern times. He wasn’t better known in his own time either. But he’s a major reason why a picture of Billy the Kid has survived some 130 years after the famous outlaw died.

Dedrick is the direct link to the Kid that sets the authenticated Billy the Kid tintype worlds apart from the newly discovered tintype.

Dedrick stepped into history in more ways than one: a bullet crippled his arm during the final five-day July battle of the Lincoln County War in New Mexico. He likely met and made friends with the Kid while fighting on the side of the Regulators. And when he took over the abandoned ranch of cattle king John Chisum, he made it a safe haven from the law for the Kid and his pards.

Sometime during 1879 or 1880, the Kid had his photograph taken in Fort Sumner, and he gave one of the four tintypes to Dedrick. Historian Frederick Nolan believes it could have been a goodbye gift because Dedrick, under indictment for larceny, left town in 1880, eventually ending up in California as a miner.

Dedrick’s nephew, Frank L. Upham, joined him in Weaverville. Before his death in 1938, Dedrick gave his nephew the tintype of the Kid, one of himself and some other photos. Eleven years later, Upham gave the photos to his sister-in-law to safeguard. Decades later, in 1986, the family loaned the Kid tintype to the Lincoln County Heritage Trust. When the trust dissolved in 1998, the tintype went back to the Upham family.

The only known photograph of the famous outlaw was not on public view again until 2011, when both the Kid and the Dedrick tintypes sold together in a Dedrick family lot at Brian Lebel’s Old West Auction. In two-and-a-half minutes, Western art collector William Koch made history himself, paying $2.3 million for the lot, which comes to about $460,000 a half square inch, if you focus only on the most valuable photo that made the lot so desired by collectors—the roughly three-inch-by-two-inch Kid tintype.

Historians did not just take the Dedrick family’s word that this is a tintype of the Kid. The tintype was identified as the Kid during his lifetime, in the Boston Illustrated Police News in January 1881. The man who shot the Kid dead that July, Sheriff Pat Garrett, published the same Kid picture in an 1882 book he partly wrote, The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid. The direct chain of custody and the contemporaneous confirmations add up to what collectors deem solid provenance.

—Meghan Saar

No Buildings on Tunstall Ranch Site

Eddie Lanham is a fan of the Croquet Kid tintype; he just doesn’t believe it was taken on the Tunstall ranch. The Georgia native is a member of the Society for Georgia Archaeology, and he is convinced the man on horseback in the

tintype is of Charlie Bowdre.

Lanham, however, has researched maps from the survey conducted in 1883, and they show convincingly that Township 15 South, Range 18 East (where the Felix School building sits today) did not have any buildings on it that year.

Since the show claims the Felix School is a match to the building in the alleged 1878 tintype, this tintype could not have been taken on the Tunstall ranch property, which had no buildings—especially not a wooden one—as of the 1883 survey.

Sage Advice

“I am not a photo expert, so I would not dare to venture that the central figure in the new alleged ‘Billy playing croquet’ photo is Billie Holiday, Billy Martin or Billy the Kid. The image of the ‘Billy’ figure in the photograph is so blurred that none of the computer bells and whistles employed on the National Geographic television special were particularly convincing. I am, however, a historian and so a photograph that has absolutely no provenance faces a Grand Canyon-sized credibility gap.

The fact that the claim is made that the photograph was taken during a particular window of opportunity when Billy and friends were together for the Bowdre wedding with no leaves on the trees and everyone wearing jackets and sweaters—does not help the credibility issue. The ‘Billy’ figure in the photo does have a familiar stance and is wearing a sweater (as Billy wears in the one undisputed image that we have), but the sweater is of a different pattern and stance proves nothing.

The owner of the photograph believes he is living every collector’s wildest fantasy and lots of folks are rooting for him. He believes in the photograph and has enlisted some persuasive allies in his quest to prove its authenticity. I fear, however, that he is simply ‘tilting at windmills.’ The whole quixotic episode proves yet again the eternal, worldwide fascination with America’s favorite bad boy. Billy would love it—but even he might say ‘buyer beware.’”

—Paul Andrew Hutton distinguished professor of history at the University of New Mexico and True West’s historical consultant

We want to know if you believe Billy the Kid is in the tintype. Tell us what you think in the comments below!

Additional Reporting By: Mark Lee Gardner, Drew Gomber, Bob Hart, Phil King, Edward Lanham, John LeMay, Sarah K. Maitland, Lynda Sánchez, Steve Sederwall and David Turk