Since Owen Wister’s The Virginian was published in 1902, Western novelists have returned to the era of the transitional West, which, according to New Mexico author Max Evans, is where “the friction occurs, and where there’s friction, there’s smoke and fire.” Master storyteller Loren D. Estleman’s 70th novel, The Long High Noon, is filled with the smouldering embers of an Old West

Since Owen Wister’s The Virginian was published in 1902, Western novelists have returned to the era of the transitional West, which, according to New Mexico author Max Evans, is where “the friction occurs, and where there’s friction, there’s smoke and fire.” Master storyteller Loren D. Estleman’s 70th novel, The Long High Noon, is filled with the smouldering embers of an Old West

that novelists have been stoking for poignancy and irony for decades. These authors include Estleman’s peer, Larry McMurtry, in his recent recitation of the Earp legend in The Last Kind Words Saloon. Like McMurtry, Estleman has mined the West for its soul in search of characters and real Western locations to explore the human condition and the seven sins that follow man through literary eternity. Estleman’s dueling protagonists figuratively and literally toil against each other in this Shakespearean saga in which their tragic-comedy of lifelong hatred leads them to their inevitable hell on a former Spanish royal road in the West’s most Western city, Los Angeles.

Like McMurtry and Evans, Estleman is interested in sifting the embers of the transitional West for allegorical tales and characters who struggle against the Sisphitic fate of time and aging. The leading men of Long High Noon would fit as easily in a William Shakespeare tragedy as in a John Ford film, but readers of Western literature will recognize the flaws they carry to their final shoot-out, similar to McMurtry’s Gus and Woodrow in Lonesome Dove, and Evans’s Big Boy and Pete in The Hi-Lo Country. Maudlin, melancholy, narcissistic, gluttonous, vengeful, sardonic, and flawed, Randy Lock and Frank Farmer make an epic journey through the detritus of the Western frontier that would make Homer smile as their paths reach a terminal crossroads at Estleman’s ironic, multi-faceted subsitute for Charon’s crossing—Los Angeles’s Cahuenga Pass.

A century ago, Los Angeles was the new capital of the American West. Emerging on the Pacific Coast, a dusty former back-water of the Spanish empire, the city of angels was attracting entrepreneurs and speculators of all ilk in land, oil, subdivisions, urban transportation and entertainment.

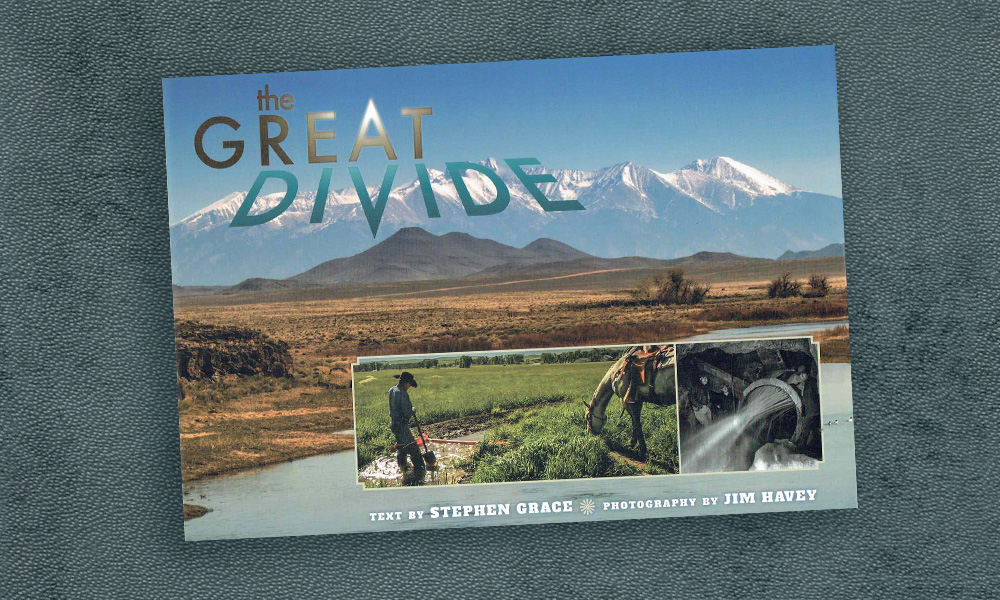

In 1913, visionary water baron William Mulholland’s first great aqueduct, which directed water from the Owens River Valley on the eastern slope of the Sierras, began pouring into the San Fernando Valley and the L.A. basin. That same year Hollywood became the center of film production in America with Gower Gulch and the upstart studios overflowing with out-of-work cowboys from across the West. Central casting didn’t need to invent the movie cowboy—the cowboys came to the city by horse, train, wagon and car. Nationally, the West was in a transition that would only become more rapid with the start of World War I. Like with Estleman’s previous Chandler-esque Western, Ragtime Cowboys, fans will wonder as they read of his twin Quixotes reaching their fates in the final pages of The Long High Noon if the Michigan author’s Western tales are nearing their end, too. At least for this fan, I hope not; there are still too many trails to ride.

—Stuart Rosebrook