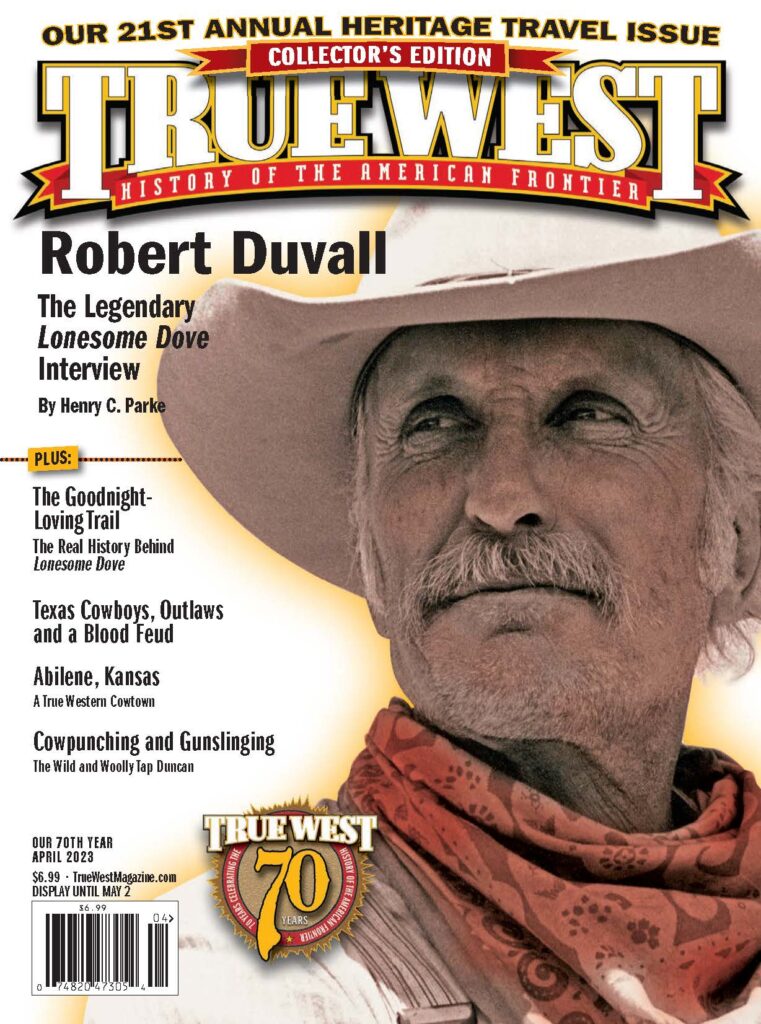

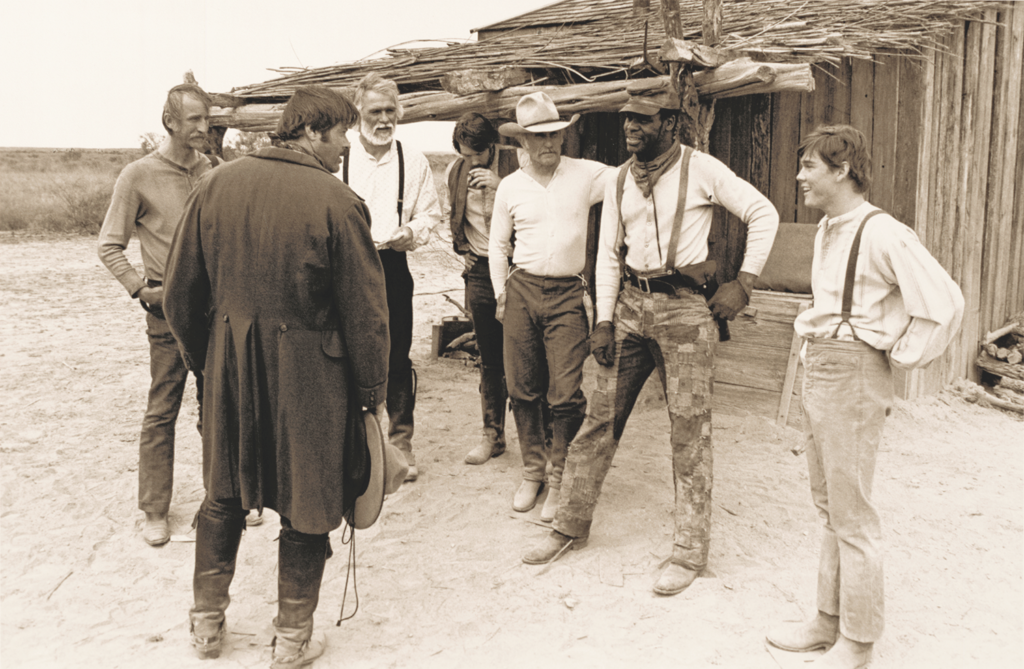

Robert Duvall talks about the iconic Lonesome Dove, on the cusp of a special cast reunion.

From the True West Archives

With seven Emmys won, Lonesome Dove is unquestionably television’s most respected Western achievement. The roles were so good, the nominations of Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones as Best Actor, and Diane Lane and Anjelica Huston as Best Actress, may have split the vote and cancelled each other out.

The miniseries had such a profound effect on the filmmakers and actors that many careers are now seen as pre-Lonesome Dove and post-Lonesome Dove. Jones had been a respected film and TV actor for nearly two decades, but Lonesome Dove made him a star. Lane’s performance solidified her transition to adult roles, as was true for Ricky Schroder, who went from teen heartthrob to leading man. With his Emmy win, Simon Wincer went from being an obscure director of Aussie TV episodes to perhaps the most in-demand Westerns director since John Ford.

Duvall, on the other hand, was already a star. Famous for his portrayal of Tom Hagen, the adopted son of Don Corleone, in 1972’s The Godfather and 1974’s The Godfather: Part II, Duvall had been nominated for Oscars in The Godfather, 1979’s Apocalypse Now and The Great Santini, and won the statue for 1983’s Tender Mercies. Millions of schoolkids knew him—and generations of them still do—as Boo Radley in 1962’s To Kill a Mockingbird. He had hardly stepped before a TV camera in 20 years, but he knew this would be no ordinary miniseries. “In fact,” he says, “on Lonesome Dove, I walked into the dressing room and said, ‘Boys, we’re making the Godfather of Westerns.’”

He spoke to True West from his home in Virginia on January 5th [2016], his 85th birthday.

True West: Do you still feel that Gus McCrea in Lonesome Dove was the best role you ever had?

Robert Duvall: Probably. There are other parts I liked. I played a Cuban barber [in 1993’s Wrestling Ernest Hemingway], with Richard Harris, which was one of my favorite parts. Man, I worked on that accent. Another one of my performances I liked was when I played Stalin [1992’s Stalin]. I try to do different things.

But I would say Lonesome Dove was like my Hamlet or my Henry V, so to speak. When it was over, I felt like I could retire; I felt I’d done something fully and completely. He was a very complex guy. He said, we killed off all the people that were interesting. That was years ago, but it was a fine character to be able to play.

How much are you like Gus McCrae?

McMurtry still thinks we [Tommy Lee Jones and I] should have switched parts, and I totally disagree with the guy.

Way back, my second wife—and I thank her eternally for this—said, ‘I read a book I like better, maybe, than Dostoyevsky’s. Lonesome Dove.’ She said, ‘They’re going to offer you the other part, but you have to play Augustus McCrea, because it’s the most like you.’

You always try to find in yourself what the character calls for. They had offered the part to James Garner. I said to my agent, ‘If you can get him to change parts, I’ll do it.’

He called back four hours later, said Garner’s got a bad back. He can’t go horseback for 16 weeks. I said, ‘Now go after that part.’

It was so well-written, the adaptation by [William] Wittliff. It was something that just drew me along. I was riding a lot of horses then, so I was very comfortable; I felt ready when we went. I had a little leverage; I wish I’d had more.

They asked, ‘Who do you want for Call?’ I said, ‘Tommy Lee Jones.’

We had a true Comanche Indian to play Blue Duck, but they wouldn’t go for that. We went to [Jones’s] ranch in San Saba; we herded cattle, riding Argentine polo saddles. He was a very open guy.

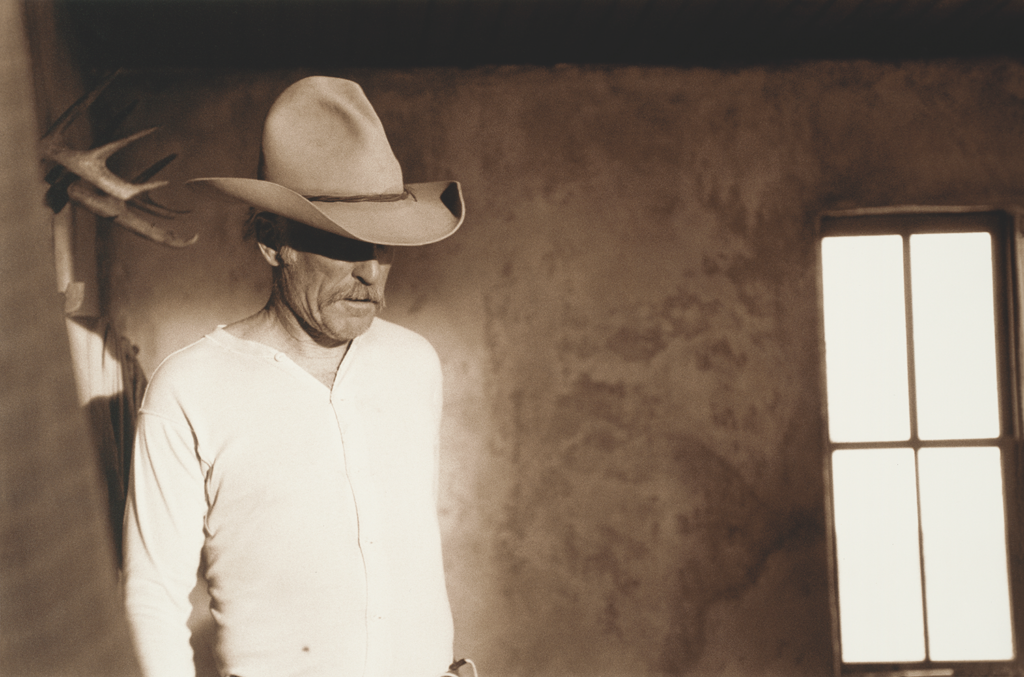

I’m told you designed the Gus McCrae hat.

They insisted, some of the powers that be, that I wear a Mexican sombrero to play Gus. I said, ‘I will not play the part if that’s the case.’

I had to go to the producers. I showed them pictures of Texas Rangers on the border, and they all wore the kind of hats I wore in the movie. I said, ‘Let me pick my own hat,’ which, finally, they allowed.

How did starring in Lonesome Dove affect your career?

It’s a lot like when I got an Oscar [1983’s Tender Mercies]; a lot more recognition in airports. Wherever I go, people refer to that.

When I was made an honorary Texas Ranger, a woman came up to me. ‘Mr. Duvall, we watch this once a year. I wouldn’t let my daughter’s fiancé marry into the family until he’d seen Lonesome Dove.’

In other places I go, too, but especially in Texas. It’s kind of a landmark for people.

There are several events coming up celebrating roughly the 25th anniversary of Lonesome Dove.

Finally! Finally! It’s more like the 28th or 29th anniversary!

I don’t know why they waited so long, but they’re going to finally do it in Fort Worth, in the beginning of April.

Will Danny Glover be there? I didn’t see his name. Way back, I wanted Morgan Freeman for that part, but he wasn’t well known that far back.

What were the other actors like to work with?

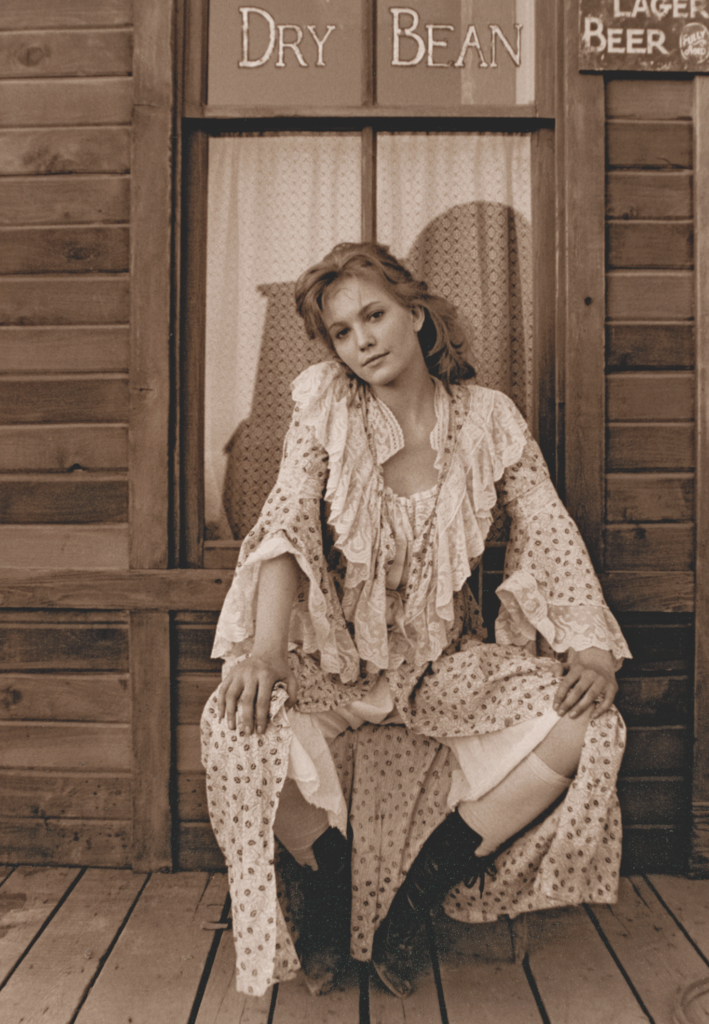

Diane Lane was fine; wonderful to work with. And Ricky Schroder. It’s interesting, because her husband, I think they’re divorced now, Josh Brolin, was up for the part [of Newt], but he was a week late, because Ricky Schroder got it a week prior.

Originally we wanted Freddy Forrest for [Robert Urich’s role], but then Freddy ended up playing Blue Duck. Robert was very nice to work with.

Anjelica Huston was great to work with. And she’d grown up riding horseback, riding on hunts with her father in Ireland.

Did you have any doubts about a non-American director for your Western?

No, Simon Wincer had done stuff. He came in well-prepared, and we went to work. And Dougie Milsom—the cinematographer—was terrific: he’d done Full Metal Jacket.

We had 16 weeks to work, and it was nice; it was concentrated. First 10 days around Austin. Then down around Del Rio, Texas, near the border. Then up to New Mexico. Then up to Angel Fire Mountains farther up in New Mexico, to suffice for Montana’s Rockies, because we couldn’t afford to go there.

I was fortunate to be in, what I think I’m correct in saying, the two biggest film epics of the 20th century: The Godfather I and II, and Lonesome Dove.

Earlier in your career, you played villain Ned Pepper in True Grit, working with two legends, Director Henry Hathaway and John Wayne.

Henry Hathaway—we won’t talk about him. But we’ll talk about John Wayne, definitely. He was a wonderful man. Good actor, good guy. So good in The Shootist at the end of his career.

Back to Hathaway. I don’t want to badmouth him, but he’s the guy who said, ‘When I say action, tense up, Goddamnit!’ There’s a difference between intensity and tenseness. I didn’t enjoy working with him, and I didn’t think he treated Kim Darby so well.

You played Jesse James in The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid.

Right. I said, ‘Let’s get Gene Hackman to play my brother, Frank.’ They said he wasn’t well known enough back then. Now he’s retired. Retired! Jesus, it’s funny.

How does playing villains compare with heroes?

You try to find the human being in yourself that will parallel what the script calls for. I call it the journey from ink to behavior; you find the behavior that the character calls for.

I always try to find the contradictions. Even when I played Stalin, I tried to find the contradictions, some kind of vulnerability in the guy, whoever it is. I could find it with Gus McCrea because he was a romantic anyway.

What does the American West mean to you?

It’s an elusive thing. Like when you go to England or wherever, they want to know about the West. That thing of pushing forward; pushing outward. The frontier.

What’s your next project?

I’m trying to get two Elmer Kelton things that have fallen through. Can’t get ’em done—Netflix or anybody.

You know, they can be Westerns, but you have to find the human thing in them, aside from horses and hats and spurs and Indian fighting. You have to find the humanness in the characters. For good and for bad, I think the Western kind of defines us. The English have Shakespeare; the French, Moliere; the Russians have Chekov. But the Western is ours, from Canada down.