Edward Curtis’s Final Adventure

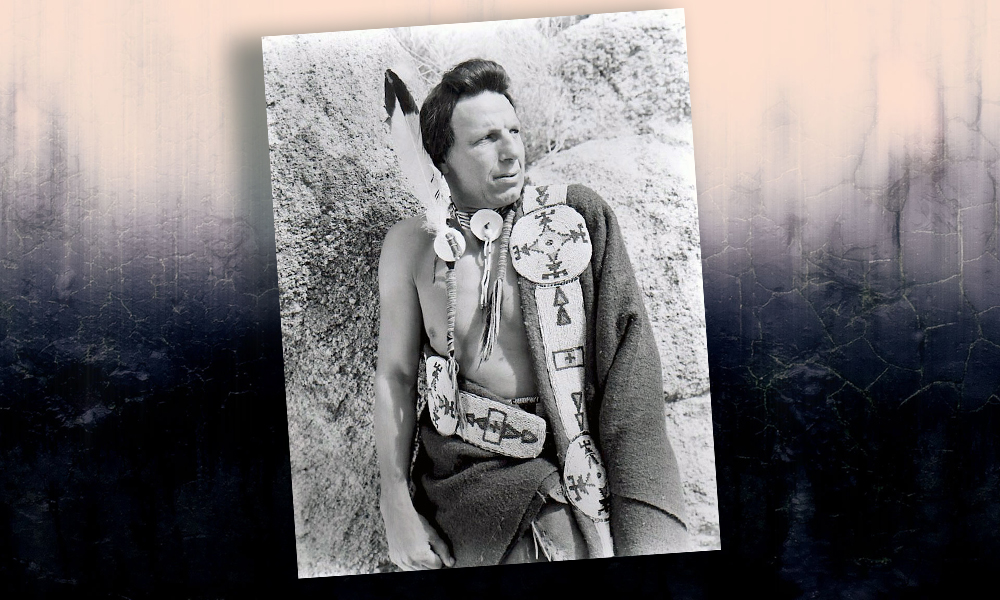

What we know: He was 59. He had a bad hip after a whale upended his boat while he was making a film. He would travel to Alaska with his daughter, Beth, a first for both of them and something that pleased him greatly.

What he knew: He knew this would be the last chapter in the adventure of The North American Indian, that the photographs he took, the languages and stories he set down would comprise the 20th and final volume in the series. He knew that he would not be able to circle back to Alaska again, as he had done with the Hopis, where only patience and persistence after years of visits earned him a place in the kiva and in the sacred Snake Dance.

What we don’t know: Even from the pages of the diary he kept, we don’t know whether or not he took the Alaskan adventure as an opportunity to look back over his life: his travels, trials, travails and triumphs.

What he didn’t know: He didn’t know that this would be the final adventure of his life. To the very end of his days, he expected that there would be other journeys. He also didn’t know that on his return from Alaska, when he arrived in Seattle, the sheriff’s deputies would be there to arrest him at the behest of his ex-wife, Clara, for nonpayment of alimony, and that he would be subjected to a humiliating, very public set of hearings. At those hearings he would describe his avocation, his passion and his single-minded drive to achieve it.

The man was Edward S. Curtis.

The month was October 1927.

In June of that year, Curtis, Beth and a college student named Eastwood, who had proven himself game on Curtis’s last trip to Oklahoma, sailed from Seattle to Nome.

They sailed past the place in British Columbia where Curtis had made the first all-Indigenous film, one that Hollywood had ginned up with the preposterous title, In the Land of the Head-Hunters (for more on Curtis’s film, see page 66). The film had been a critic’s darling and a box office dud and had cost Curtis dearly, even more if you count his whale-smashed hip.

Before that, back in 1899, Curtis had been the official photographer on an Alaskan expedition organized by railroad robber baron E. H. Harriman. The ship they took was well-stocked with the following: milk cows, a grand piano, good champagne, better whiskey (I’m guessing about the whiskey) and top-notch naturalists including John Muir, John Burroughs, Gifford Pinchot and George Bird Grinnell, whose observations of abandoned Native villages on their journey led him to invite Curtis to accompany him to Blackfoot Country. Grinnell felt that the Indigenous peoples of the Americas were a noble but “vanishing race,” and that it would be a race to record their likenesses, languages, ceremonies and customs, for they were sure to die out before another century passed. From our vantage point, it seems that in the minds of these naturalists and anthropologists, the buffalo, the wilderness and the “Indian” became entangled. It is strange that these men labored to save the buffalo and set aside some wilderness, but thought that the “primitive” Native American was doomed to extinction by the pressures of modernity and Western “civilization.” Nevertheless, from these men and their contemporaries was born the myth that fired Curtis’s imagination and caused him first to neglect and then to forget the thriving portrait business he had built in Seattle where he had a name and reputation, where he could have amassed a small fortune and lived quite comfortably with his family taking artful pictures of brides, debutantes and captains of industry.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Comfort was something Curtis rarely knew after 1899.

Nome was the first stop in Alaska in 1927. A gold rush boomtown in 1899, it was spectral now, played out, derelict, an emblem of the rise and fall of empires.

All Images Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Unless Otherwise Noted

Curtis had felt, firsthand, the sting of the metaphor of the rise and fall. He had received the blessing of Theodore Roosevelt and had been backed by J.P. Morgan. He had been one of the toasts of New York. He wrote in a 1949 letter to Seattle librarian Harriet Leitch, “Some winters where we [Curtis and “Buffalo Bill” Cody] were both in New York we palled about a bit and were dubbed the ‘Cody twins.’” Since its inception in 1900, however, Curtis had sunk every penny into The North American Indian, rarely drawing pay for himself or his family. Not long after the publication of Volume 20, the Alaska volume, Curtis signed over all rights to the Morgan heirs and went to live near his daughter Beth, in Los Angeles He continued to dream big dreams: of a history he would write that he would call The Lure of Gold, and of a last great trek to the Amazon.

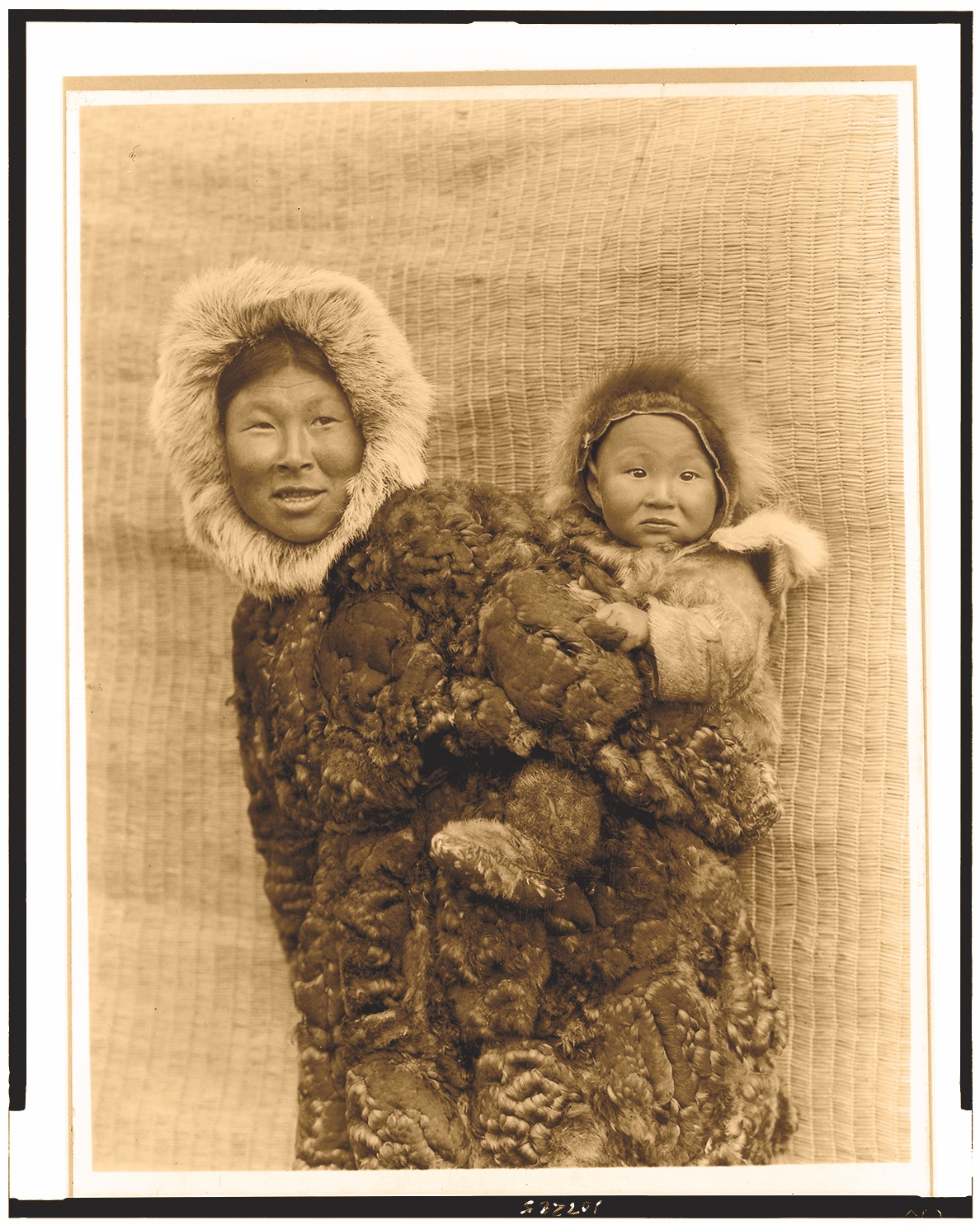

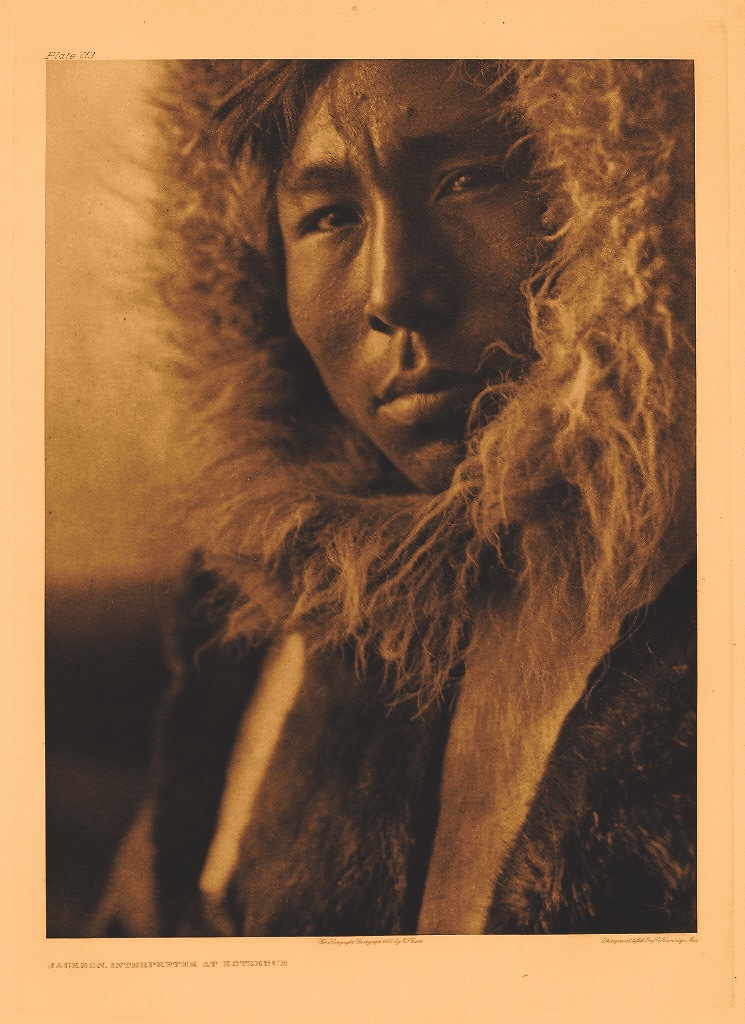

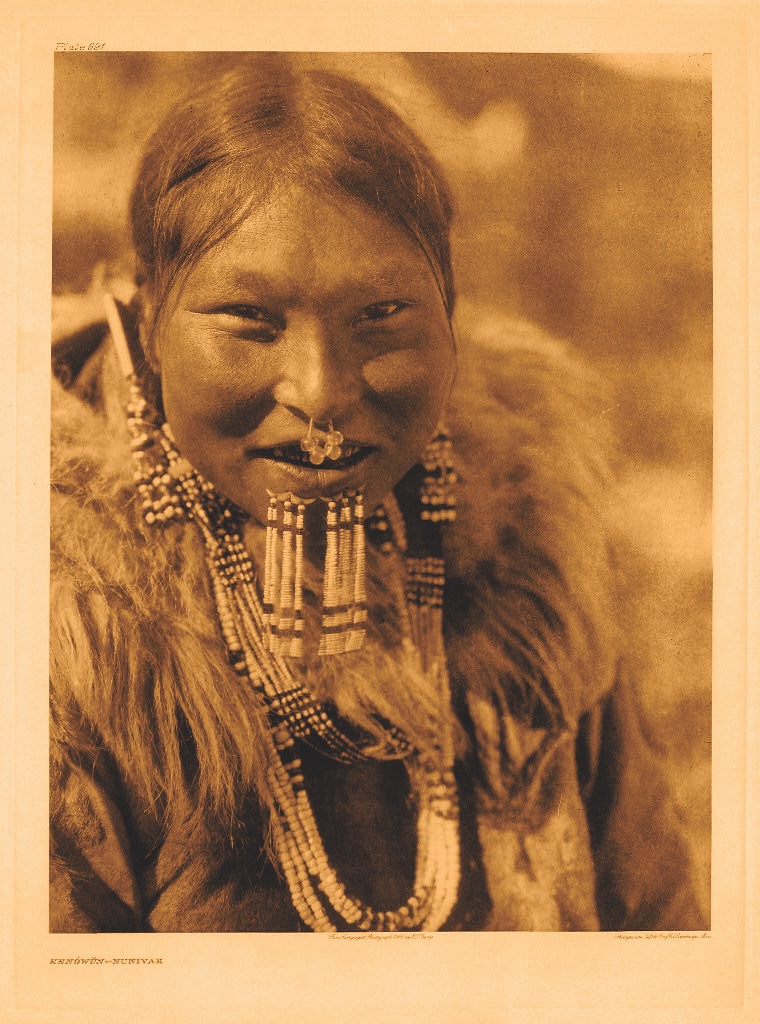

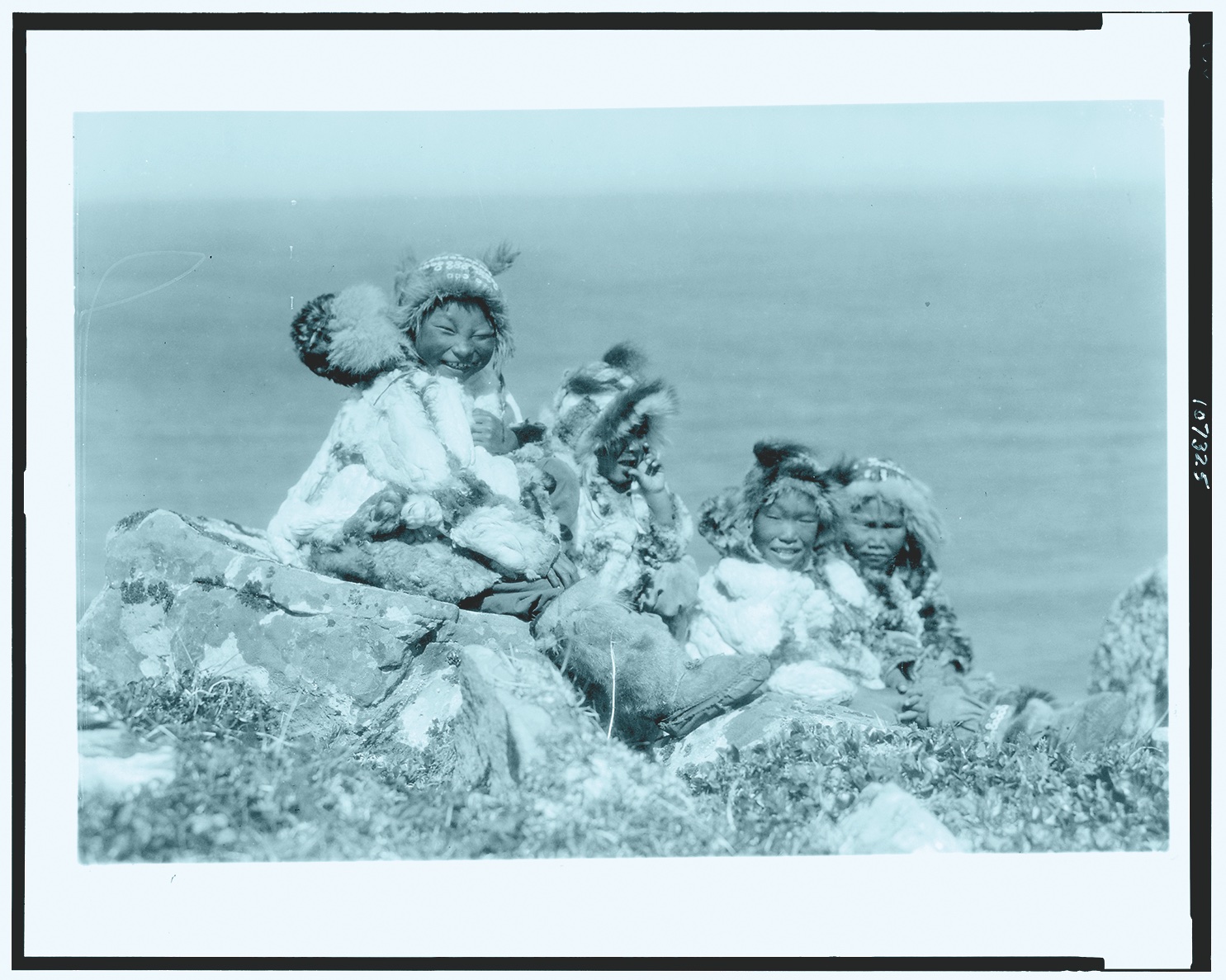

On July 10, 1927, the Curtis party reached Nunivak Island. Curtis was thrilled because while there had been Russian and American visitors to the island, there had been no proselytizing, so the stories and ceremonies in the Yupik dialect spoken there went on unchecked by Christianity. “Should any misguided missionary start for this island,” Curtis wrote, enlisting the natural world as his ally, “I trust the sea will do its duty.” Yupik tales and masks made their way to the Surrealists in New York and France, as recent exhibitions at the Heard Museum and elsewhere have revealed, and they exerted a powerful influence on the late work of Henri Matisse. Curtis reveled in Nunivak artistry and in the fact that these people smiled, broadly and often, as opposed to most of the Native Americans he had photographed. To him, Nunivak was sufficient unto itself, her people skilled at making kayaks and sewing skin coats, and hunting caribou on land and whales at sea. They fought and celebrated life on their own terms, from within their own cultural traditions, not on the terms of settlers or missionaries.

Look, for example, at the portrait of the young Nunivak woman, Kenowun. Her aspect is confident, curious, exuberant; her beaded piercings are nothing short of stylish. She seems entirely herself. One wonders whether, at the time he took this photograph, Curtis’s notion of the “vanishing race” might not have trembled, even crumbled at the edges. In fact, if I am correct, Kenowun had been photographed by Alaskan warden W.B. Miller two years earlier. In that photo, she stands by the wheel of a ship holding a child. Vanishing? Hardly.

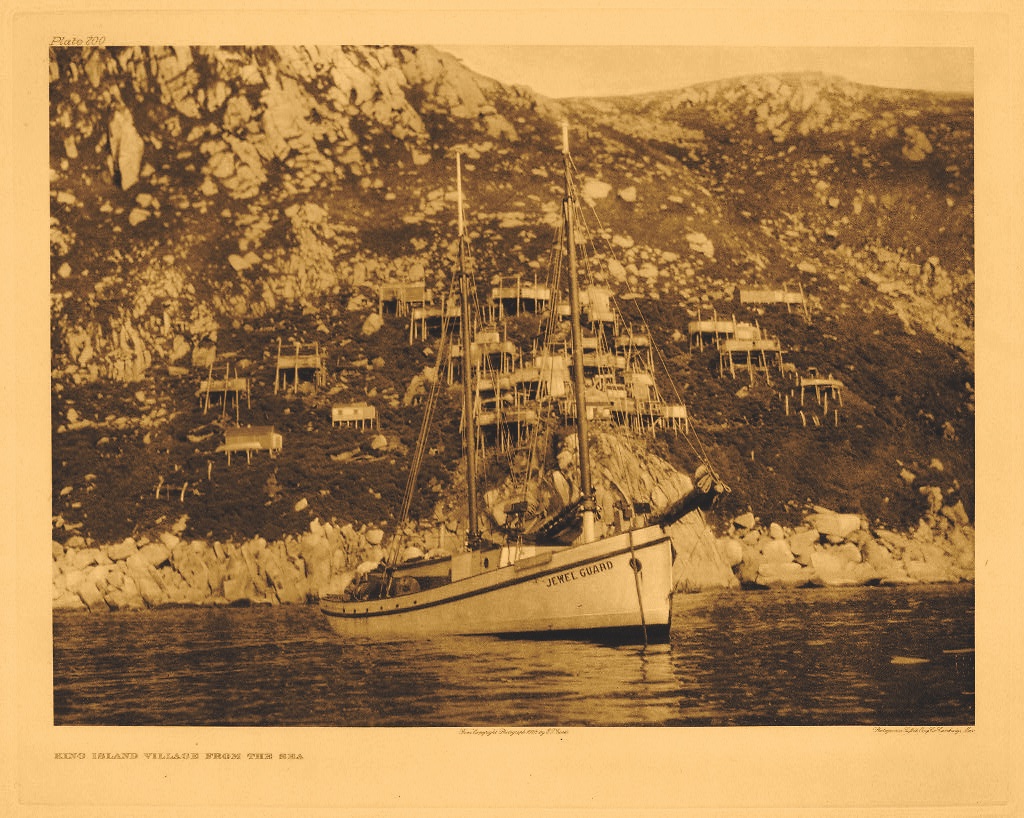

The dwellings on stilts Curtis scaled to explore—defying his whale-smashed hip—on King Island circled him back to the Pueblos of the Southwest. The place was deserted. As Timothy Egan wrote in his Curtis biography, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, “Everyone was away, Curtis surmised, and would take up residence only during the peak of the walrus migration.” Curtis himself wrote, “The village is like no other on the continent. These people may well be called North Sea Cliff Dwellers.” Curtis, who devoted himself to evidence, makes no explicit connection between Peoples of the Arctic and of the Southwest but leaves it to the reader to speculate on cultural transmission over time and across a continent. An image of Curtis’s vessel, the Jewel Guard, floating in front of the village clinging to the cliff, seems an apt metaphor for the fragility of the artist’s and all human endeavor.

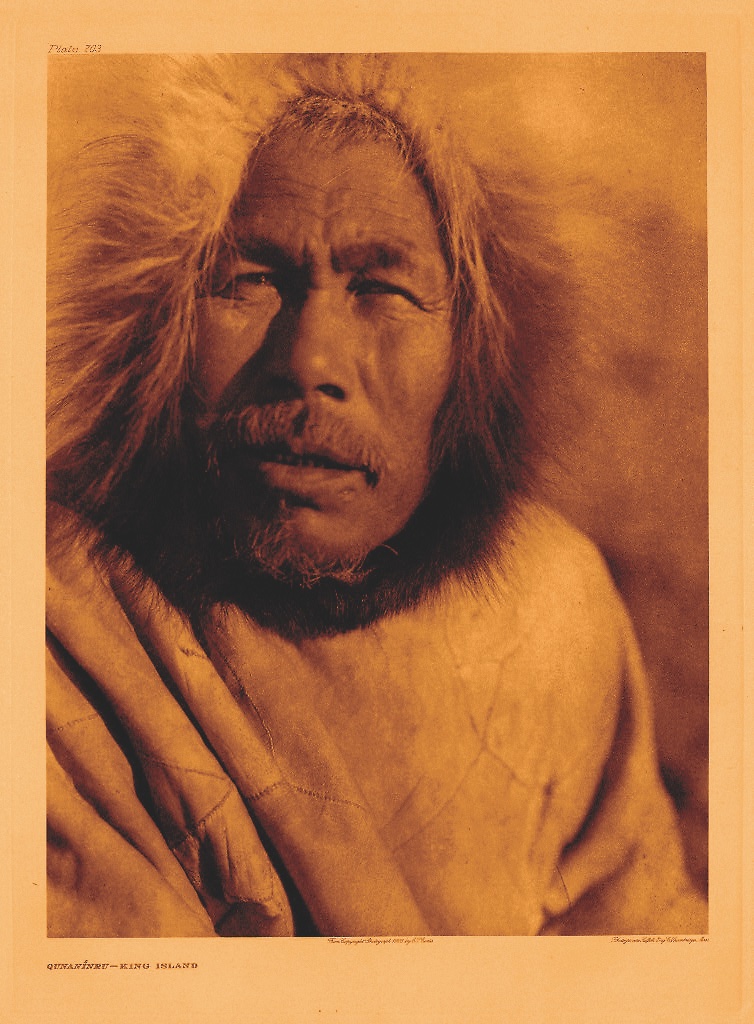

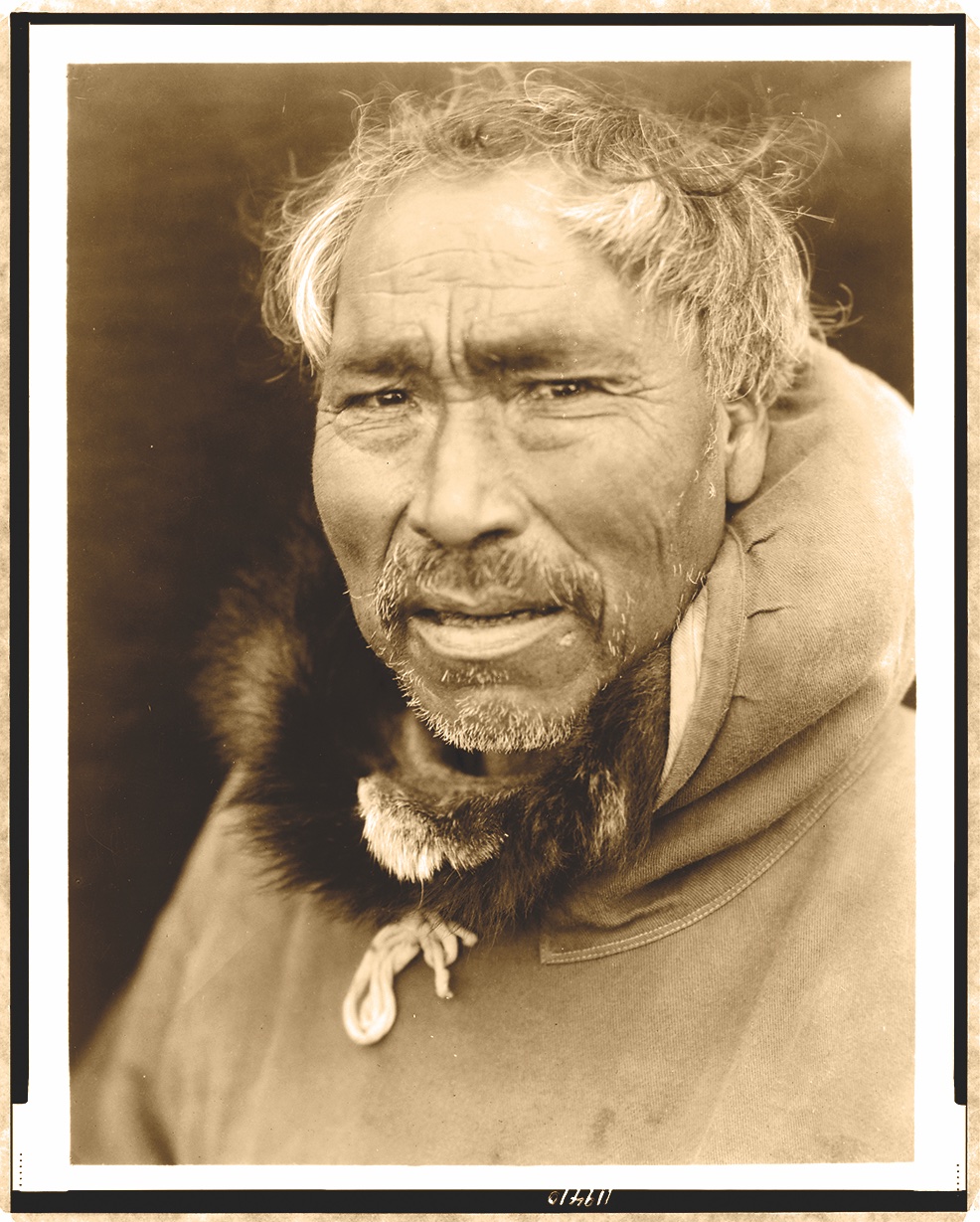

Curtis would get as far as Little Diomede Island, just this side of the International Date Line in the Bering Sea and within hailing distance of Big Diomede Island, the easternmost extremity of the Soviet Union. Looking for Natives who had been least affected by European settlement had led Curtis to these remote and inhospitable islands. Perhaps instinctively, he had ended his journey by circling back in time to the places where the first First Peoples had crossed to the American continent from Asia—whether by land bridge or by boat is a current matter of debate.

Images Courtesy Library of Congress

After an ice storm nearly sank his boat on their return run to Nome, and their arrival had been delayed, Curtis was declared lost at sea. But when reports of his demise turned out to be greatly exaggerated yet again—this was the second time Curtis had been deemed dead—Clara saw the news of his resurrection—she no doubt saw it as ornery unkillability—and called in the sheriff. Which is where we came in.

If it hadn’t been The North American Indian, Edward Curtis would have heard some other calling, something to complete that could never be completed, something to perfect that could never be perfected. He would have found a hip-smashing white whale to play Ahab opposite. That’s who he was.

Envisioning Curtis’s response to those who asked how he did it, Egan summarizes the complexity and sheer impossibility of the task Curtis set for himself, writing, “You had to understand the essence of a thing before you could ever hope to capture its true self. And yes, he was trying to bring a painterly eye to the process, a subjective artistry… [N]o two people could point a camera at something and come away with the same image. But, of course, photography involved a mechanical side as well, and there, too, you could shape the final product to match a vision—to bring the right image to light from a stew of chemicals, to touch it up in a print shop, to finish with an engraving pen. Curtis never turned it off, never took time to play or let his mind roam, even at home.” At the trial, Curtis broke down, as if the sacrifice his passion had required had flooded over and through him, and said, “It was my job. The only thing… the only thing I could do that was worth doing.”

The cultures of Indigenous Americans today are thriving and growing as they assert their voices in politics and the arts and lay claim to their lands, rights and languages—Curtis’s work in Indigenous linguistics has been of assistance in this. Buffalo continue to roam, though not exactly wherever they might like. Wilderness, however, is a beleaguered, circumscribed thing. Edward Curtis in 2021 might find himself going back to his beginnings, leading tours to Mount Rainer, and aligning himself with Sir David Attenborough, filming retreating glaciers and endangered species.

One of the Nunivak stories recorded in Volume 20 begins, “There was a time, long ago, when a man all at once became conscious of himself…” From consciousness, the man ventures out into the world, to complete and fulfill himself. I find myself feeling great empathy for Curtis. I, too, am 59. I haven’t led the life he has, but I have led a life—a life that, like his, has sometimes led me. The sheriff’s deputies aren’t waiting for me—not so far—but I do circle back to the turns I made and didn’t make, as I am sure he did when he sat before the judge in that courtroom. Yet I wake every day, as I know Edward Curtis did, with the feeling that I have one more adventure in me, one more, and then I say to myself, sometimes even out loud, “At least one.”

James D. Balestrieri is the principal of Balestrieri Fine Arts. He currently serves as communications manager for Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, estate and collections consultant for The Couse Foundation and Writer-in-Residence for the Clark Hulings Fund.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Courtesy Library of Congress