Southeastern Arizona was contested ground. The few Americans who dared its dangers called the region the “Purchase,” after the 1854 Gadsden Purchase from Mexico that had added the Mesilla Valley and the land south of Arizona’s Gila River down to the 31st degree of latitude to New Mexico Territory. The Spanish and the Mexicans had called it Apacheria, after the Indian tribe that frustrated their efforts to settle the land.

Charles Poston, the self-styled “Father of Arizona,” had reached an agreement with Mangas Coloradas, greatest of the Apache chiefs, to allow his miners and lumbermen to work the land south of Tucson unmolested. Poston had also lobbied Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to provide troops to protect his new mines.

Poston’s Sonora Exploring and Mining Company established its headquarters at the abandoned Spanish presidio of Tubac in 1856. Not long after, Capt. Richard Ewell of the 1st Dragoons, later to be a famed Confederate general, established Fort Buchanan on a plateau above Sonoita Creek, just to the east of Tubac. This most isolated outpost of the republic had no outer walls and was constructed of logs chinked together with adobe. It offered little in the way of protection to the settlers, but it did open a valuable new market for cattle and crops to them. By the end of 1856, as Poston’s mining company thrived, nearly 1,000 people were settled around Tubac.

Critical to this repopulation of the Santa Cruz Valley was Poston’s agreement with Mangas Coloradas. While Chiricahua Apache raiding parties continually traveled past Tubac on their way south to raid in Sonora, they usually did not molest the miners, ranchers, lumbermen or farmers. Although the land remained wild and dangerous, with American and Mexican outlaws everywhere, Poston felt as if he had founded a frontier Eden: “We had no law but love, and no occupation but labor. No government, no taxes, no public debt, no politics. It was a community in a perfect state of nature.”

About 30 miles to the east of Tubac was the Sonoita settlement, which consisted of seven ranches along the dozen miles of the valley floor. The census of 1860 listed 51 citizens in the valley, identified as farmers, teamsters, laborers, a cook, a clerk, a shoemaker, a lawyer, a printer and one simply as an “idiot.” Fort Buchanan provided nominal protection, for the soldiers could barely guard their own horse herd, and Apaches once made off with several of the officer’s tents. Not far from the fort stood the local general store of White and Grainger. Four miles south of the fort was James “Paddy” Graydon’s United States Boundary Hotel, a rollicking establishment that everyone called Casa Blanca. Just below Graydon’s saloon was the ranch of Felix Grundy Ake, who had settled there with his tempestuous brood in 1855. Johnny Ward’s ranch, at the western bend of Sonoita Creek, was next in line, followed by the farms of William Wadsworth, B.C. Marshall and old Elias Green Pennington, and finally a gristmill operated by William Finley and Nathanial Sharp. The Sonoita Valley, proclaimed Tubac’s The Weekly Arizonian, was a “treasure beyond price to the farmers in the neighborhood.”

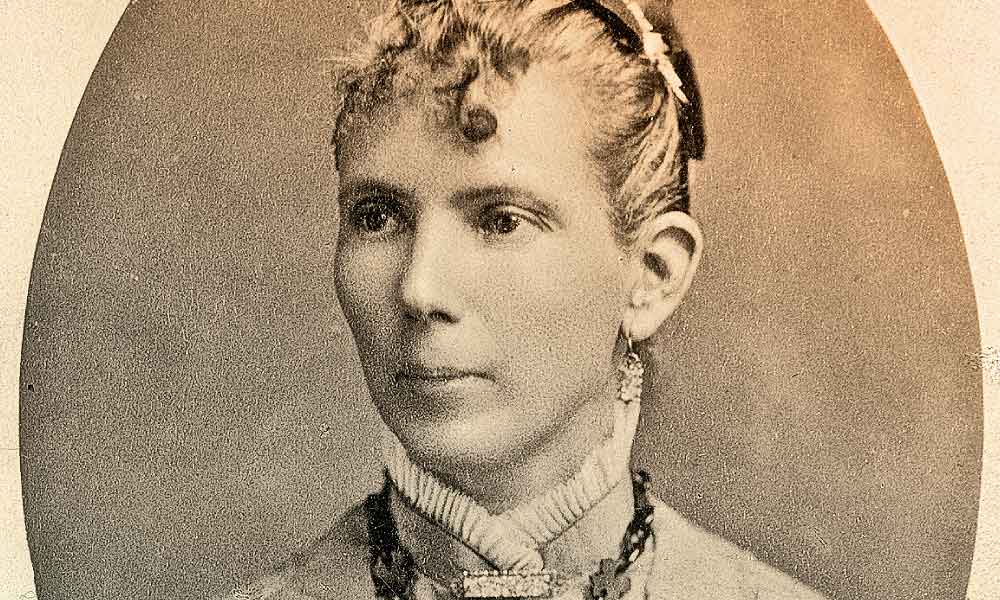

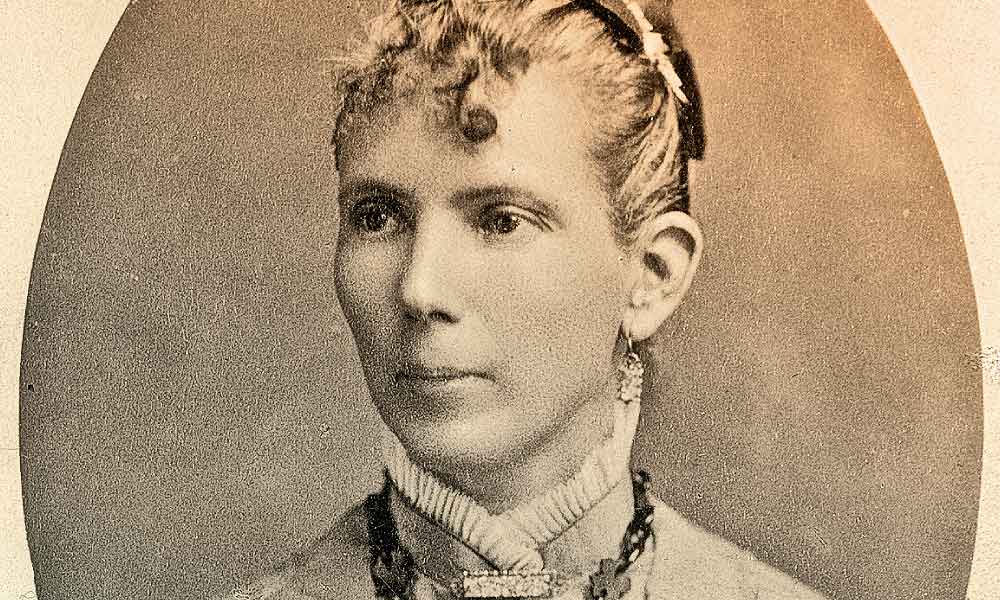

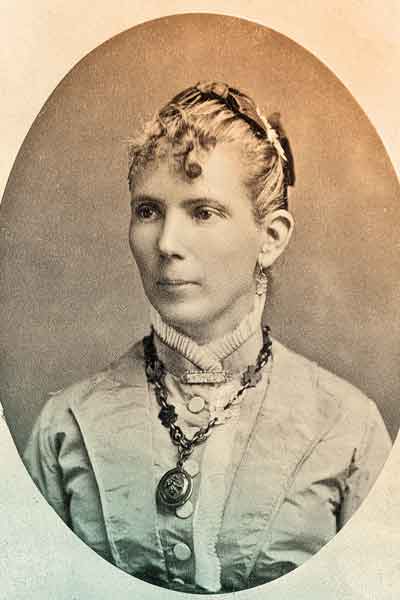

In time, a few American women also came into the valley. The most noted were the daughters of the eccentric Elias Pennington. He was known to all in the “Purchase” as Old Man Pennington and was a true pioneer as well as a wild, roving spirit. He had moved his growing family from Tennessee to Texas in 1839, but after the death of his wife, he pushed on west. He ran out of steam, but not determination, in June 1857 at Fort Buchanan while en route to California. His daughter Larcena had come down with a fever. While she recuperated near the fort, the Apaches ran off several of Elias’s oxen. Making the best of a bad situation, Elias moved his brood of 12 children—four boys and eight girls—down to the east bank of the Santa Cruz River, close to the Mexican line, where the family dug irrigation ditches and planted crops. The family sold their crops to the soldiers at the fort and to the miners at Tubac. The Apaches did not molest them.

Belles of Santa Cruz Valley

In the eyes of his neighbors and, most especially, the soldiers at the fort, Elias knew his success as a farmer was overshadowed by the lovely crop of daughters he raised on the farm. “I had the pleasure of an introduction to the eccentric old Pennington,” J. Ross Browne noted. “Large and tall, with a fine face and athletic frame, he presents as good a specimen of the American frontiersman as I have ever seen. The history of his residence in the midst of the Apaches, with his family of buxom daughters, would fill a volume.”

Dr. John Hall, a remarkable British soldier of fortune who had spent a considerable time in Sonora, arrived in the Santa Cruz Valley in the summer of 1857. He attended a Christmas gathering at a ranch near the fort at which the Pennington girls created quite a sensation. “But few ladies, American, graced the party, but those present were the ‘belles’ of the valley, good looking and true specimens of frontier coquettes,” he recalled. “Womankind (white) are scarce in Arizona, so all the young squatters present were deeply smitten.”

Captain Ewell, who Hall called an “inveterate old bachelor,” enjoyed the scenery immensely. Hall was perplexed by the small stick the American girls had in their mouths. Ewell explained to the well-travelled Englishman that this tobacco-laden stick and this practice of “mopping” were common on the frontier. The little stick was the mop.

Hall was mortified. “It is abominable, even worse than crinoline,” the Englishman huffed. “A Mexican woman may be excused her cigarette, a Hindoo her hookah and an Irishwoman her short ‘dundeen,’ but a pretty American girl a ‘mopstick!’” Dr. Hall was learning just how quickly the social conventions broke down on the frontier.

Of all the Pennington girls, 22-year-old Larcena was by far the loveliest, breaking the forlorn hearts of many a lonely soldier and miner. She finally married handsome John Page on Christmas Eve 1859 in Tucson. Page was one of the wildest spirits in the valley. He had come to Tucson with the notorious gunman Bill Ake in April 1857. Ake and Page were part of a turbulent group of young toughs that a later generation would label with the epithet “cowboys.”

After their wedding, Page took his bride to William Kirkland’s Canoa ranch on the Santa Cruz River. Kirkland, a tall, imposing, 27-year-old bachelor from Virginia operated a thriving lumber business, servicing both Tucson and Fort Buchanan. While Page felled timber 13 miles to the east in the mountains, Larcena tutored Kirkland’s ward, Mercedes Sais Quiroz, the bright 10-year-old daughter of a Mexican widow who lived in Tucson.

Larcena fell ill at the Canoa ranch.

The wetlands along both the Santa Cruz River and Sonoita Creek bred legions of mosquitos that carried malarial fevers, while fungus-laced spores from dust also infected settlers with sometimes deadly fevers that were totally misunderstood

for another century (called Valley

Fever in Arizona today). The mountain

air of the lumber camp was deemed to be good for her, so, on March 15, 1860, Larcena and Mercedes climbed onto an ox-drawn supply wagon headed for the lumber camp. The little girl cradled Larcena’s small dog in her lap. Kirkland, fretting over this outing, dispatched William Randall, an old frontier hand, to accompany the wagon on horseback. Kirkland also thoughtfully sent along a rocking chair and featherbed as gifts for the newlyweds.

As the oxen struggled to pull the wagon up Madera Canyon to the lumber camp, five Tonto Apaches watched and waited. While Mangas Coloradas might hold his Chiricahuas in check, even he could not control the Apache bands north of the Gila.

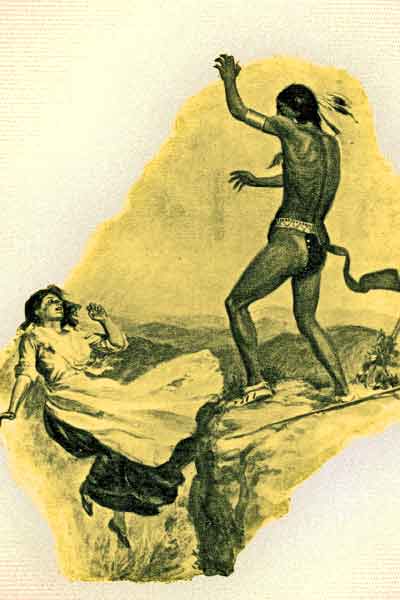

The Apaches Attack

After an early breakfast, Page and the other woodcutters headed higher up the mountain slope while Randall went off to hunt venison for supper.

As Mercedes played, Larcena eased into the rocking chair in her spacious tent. Her little dog lay curled up beside her. When the dog began to growl, Larcena hushed him. Then she heard Mercedes scream.

As she rose to her feet, the tent flap flew open and an Apache burst in. She reached for the Colt revolver by the featherbed, but the warrior grabbed her arm and pushed her out of the tent.

Mercedes ran toward Larcena, only to be seized by another Apache. Larcena now saw all five Apaches, half-naked, wearing but breechcloths and high-topped moccasins, and all armed with lances and bows and arrows. They were all young, save for an older warrior who spoke broken Spanish. She started to scream again for help, but a lance pressed against her breast silenced her.

The Apaches ransacked the camp, looking for anything of value. Since they were afoot, they could not carry anything heavy, so they amused themselves by cutting up bags of flour as well as Larcena’s featherbed. Feathers mixed with flour filled the air. The Apaches gathered up what they could carry and then marched Larcena and Mercedes up the steep slope toward their northern homeland.

Randall returned at noon to find the camp ransacked and the girls gone. He rushed to alert Page and the other lumbermen. A frantic Page mounted Randall’s horse and galloped to Canoa. The horse died under him as he reached the ranch and breathlessly told Kirkland what had happened.

Kirkland sent a messenger to Fort Buchanan. Then he rode the 40 miles north to Tucson for help. Page and another ranch hand mounted fresh horses and headed back into the mountains in search of the Apaches’ trail.

Trail of Desperation

Larcena made certain the rugged trail was well marked, breaking twigs and tearing pieces from her apron and dropping them. She whispered to Mercedes to do the same, but an Apache overheard her and separated them.

The Apache who had taken her revolver pointed it at Larcena’s head and taunted her in broken Spanish. Mercedes, understanding that he said he would soon kill Larcena, called out a warning and began to sob. The largest of the Apaches, for they were all small and wiry, hoisted the little girl onto his shoulders and carried her up the ridgeline.

The climb up the mountain was difficult, and Larcena, weakened by her illness and encumbered by her long dress, slowed the Apaches. As sunset neared, they halted on top of a ridge. The view, with a steep drop off to one side, was breathtaking. A warrior who had been acting as a rearguard clamored up the rocks to tell them that the White Eyes were coming in pursuit.

The older Apache motioned for Larcena to remove her dress. As she stripped to her chemise, another warrior demanded her shoes. He then ordered her forward.

Larcena had hardly taken a weary step before the first lance pierced her back. She fell sidewise down the cliff. As she tumbled across the rocks, she could hear Mercedes scream and the Apaches whoop. She lodged against a small pine tree, almost oblivious to the repeated lance thrusts from the two Apaches who had slid down next to her. One of the warriors picked up a large stone and smashed it against her head—then all was a blessed oblivion.

On the ridgeline, the other Apaches muffled the child’s anguished cries and hurried on toward the northeast. One warrior picked up Larcena’s dress, while another put on her shoes.

A Missed Rescue

In twilight, Larcena regained consciousness. She could hear her little dog barking on the ridgeline above her. She thought she heard her husband’s voice cry out, “Here it is boys!”

The men had been puzzled by the wild confusion of the tracks on the trail. The excitement of the dog had led them to stop right above Larcena, but in the dim twilight, they could not see her. Page had discovered the tracks of her shoes farther up the ridgeline, and he and the others hurried on in pursuit of the Apaches.

Larcena tried to call out, but she was too weak to make a sound. As the voices faded away, she slipped back into unconsciousness.

– All images courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton Collection –

The Negotiation

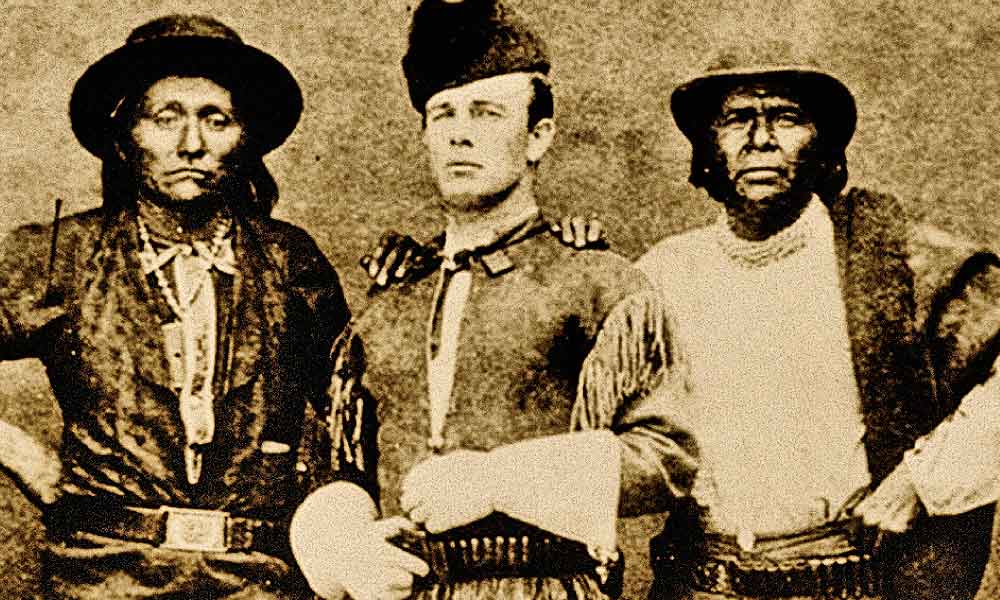

Captain Ewell had a mounted detachment in the field as soon as Kirkland’s message reached Fort Buchanan. Don Antonio Gandara, son of the former governor of Sonora, led a party of 28 Hispanics from Tubac, while the Papagos provided 17 good trackers.

On March 17, before dawn, Ewell rendezvoused with Kirkland and a civilian posse from Tucson on Ciénega Creek, some 35 miles southeast of Tucson. They could see that the Apaches had divided into two parties and headed north of the Overland Mail route. The tracks they were following were the articles of clothing Mercedes had dropped along the trail, as well as occasional sideward steps she had left in the soft sand along the flats. The other party of Apaches had also been tracked, but no sign showed Larcena with them.

Everyone assumed the kidnappers to be from Eskiminzin’s band of Aravaipa Apaches, who lived along Aravaipa Canyon where it opened into the San Pedro River.

Twenty Pinals captured in a December skirmish with Ewell’s dragoons were being held at Fort Buchanan. The captain compelled several of these men to act as trackers for his column as they moved north of Tucson into the Catalinas.

The trail led directly to the Aravaipa homeland. Ewell gave one of the Apache prisoners a dragoon mount and sent him to Eskiminzin’s village to open negotiations. Kirkland sent along two fine Mexican blankets to sweeten the bargain. Ewell informed the Apache messenger that he would wait for eight days at Canyon del Oro for a response, but warned him that any hesitation in returning the girls would result in dire consequences for the male Pinal prisoners still held.

A few days later, the Apache returned to Ewell with a message from Eskiminzin. They had not taken the captives, the messenger explained, but they could ransom the little girl from the Tontos who held her. The woman was dead. In exchange for the girl, Eskiminzin sought the Pinal captives and two wagons full of goods.

A grieving Page carried Ewell’s order south to Kirkland in Tucson, requesting he retrieve the Pinal prisoners from the fort and bring them to the dragoon camp. “There was no hesitating about acceding to the Indian’s terms, one sided as they were,” Kirkland remarked, “and every effort was immediately put forth to carry the agreement into effect.”

In Tucson, the general sentiment was that the Apaches were lying. “If the Pinals can be believed, they are the most peaceable Indians in the world,” a local reporter noted.

Captain Ewell, however, was convinced that their story was true and that the Tontos were the guilty party.

Collecting his prisoners and two wagons of goods, Ewell marched to the main village at the mouth of Aravaipa Canyon. The San Pedro River bank was “literally swarming with Indians,” a nervous Kirkland noted. “I never saw so many in my life.”

Ewell was cautious, lining his soldiers up with weapons at the ready as the Apaches approached. He ordered the Apaches to send Mercedes to him and, at the same moment, commanded his soldiers to release the prisoners from the wagons. Mercedes ran past the captain to Kirkland, who swept her up in his arms. She told him she was hungry.

Ewell got his people away from Aravaipa Canyon as quickly as possible. Two days later, on April 5, the column approached Tucson. The captain loaned Kirkland

his own fine horse to ride with Mercedes into the old walled town. Church bells rang as all the citizens turned out in joyful celebration. Kirkland made his way through the milling crowd to the plaza where he delivered the little girl into the arms of her tearful mother. They were instantly mobbed. “The little girl, now a heroine indeed, passed from one to another to receive their embraces, congratulations and welcome,” an eyewitness wrote.

A grand military ball featured Ewell and Mercedes as the guests of honor. All recognized that the captain’s knowledge of the Apaches and wise restraint had redeemed the little girl from captivity. Ewell was one officer who knew when not to fight.

Mercedes grew up to be a delicate and beautiful young woman. She was 18 when she married Charles Shibell in 1867. Her husband, a former soldier, became Pima County sheriff in 1876. She died at age 26, in December 1875, of complications from the birth of her fourth child.

Still Alive

Larcena woke in a snowbank, lodged against a pine tree. She melted snow in her hands to drink and attempted to wash her wounds.

She had been stabbed repeatedly

in the back, but she could not reach the lacerations to clean them. Her head throbbed, and her blonde hair was a mass of clotted blood. She had no idea how long she had lain unconscious against the tree—a day, two, perhaps three.

The sun was warm. She drew strength from it. She was naked, save for her chemise and petticoat. She slowly gathered her wits and her bearings. Looking westward from her precarious perch, she could make out Huerfano (Orphan) Butte, in the Santa Cruz Valley. The cone-shaped hill, a solitary sentinel on the desert floor, was the last thing she remembered seeing before the lances struck her. It was her compass.

Larcena knew the butte was just to the northeast of the Canoa ranch. She was far too weak to crawl back up to the ridgeline, so she eased herself as best she could down the mountainside. Every inch was agony. When she finally reached the level ground below, she fainted and slept until the next morning.

The warmth of the morning sun aroused Larcena. She painfully pulled herself up and braced against a tree. She dared go no farther down into the valley since she knew it held no water. The tree-shaded mountains still offered a few patches of snow. Using the distant Huerfano Butte as her guidepost, she began making her way toward Madera Canyon and the lumber camp. Each bare-footed step was agony as she struggled across the rocks, thorns and brush. She had not gone far before she collapsed.

Larcena soon lost track of the days. The warmth of the sun would wake her from the frigid night, but it also beat down on her, burning and blistering her fair skin. She melted snow in her hands and drank, ate grass and berries and once found some wild onions that boosted her spirits. Her feet were now lacerated, with pebbles working under the skin through the open wounds, so that she could no longer walk. Sometimes she moved like an animal on all fours, but usually she simply crawled.

She came upon a large nest of dried grass and crawled into its warm embrace. She was almost asleep when she realized that she was in a bear den. She crawled away as far as possible and scratched a hole in the sand for her bed.

The mountains provided few easy passages. She crawled up a steep ridge only to lose her balance and slide back down. She wound up farther down the mountain than where she had begun. It took her another full day to regain the lost ground. The skin on her arms and legs were lacerated so badly that the skin peeled away from the bone.

She kept on, driven by an indomitable will that defied all the physical obstacles, heartbreak and pain that raw nature could inflict on her. She crawled day after miserable day, curling up into a pathetic ball of torn flesh night after freezing night.

Then, amazingly, one morning after the sun had warmed her enough so that she could move, she found herself on a ridge high above the road leading into the canyon and up to the lumber camp. She heard voices and saw two men driving an ox team up the road. She screamed as loud as she could, but they did not hear her. She ripped off her tattered slip and tied it to a stick and waved it, and waved it, and waved it. Then they were gone. She had no tears left to cry with.

The Ghost at the Camp

Larcena knew the lumber camp must be close, perhaps only a mile or two away. She crawled on. A day passed, then another, until finally she found herself back in the ransacked camp from which she had first been taken.

Flour and coffee still lay in piles on the ground. She picked the flour out of the feathers from her ruined featherbed and made little flour cakes. The men had left a fire smoldering by the creek, and she breathed life into the red coals. Crawling to the creek, she mixed water with the dough and cooked it. She ate her flour cakes and then slept.

When she awoke, she heard the welcome sound of distant voices and the thud of axes against trees. Unable to muster the strength to rise, she crawled toward the trail that led up to the pinery at Big Rock. She was nearly naked, burned red by the sun, and a mass of bones to which torn skin clung in tatters.

At the pinery, the woodcutters’ main camp, lived a black cook from Texas named Hampton Brown who, with his white common-law wife, had found work in this most isolated and distant of frontiers where their dangerous union might be tolerated. Kirkland referred to them as a “notorious Texas Negro known as Nigger Brown and his white woman known as Virgin Mary.”

Brown thought Larcena to be a ghost. He had been walking down the trail when he saw the white-clothed figure, bloody hair hanging down in front, crawling toward him. He ran back to camp and got his gun, and with several others, returned to investigate this ghostly apparition.

The figure gasped out that she was Larcena Page.

Brown put aside his gun and picked up the frail, emaciated woman in his strong arms. He carried her to camp, where the Virgin Mary tenderly washed Larcena, removed the stones from the soles of her feet and the thorns from her flesh, cleaned out her festering wounds and fed her. She then carefully dressed Larcena in clean clothes.

Larcena asked for some tobacco and then went to sleep. Fifteen days had passed since the Apaches took her.

– True West Archives –

Hope Conquers

Tom Childs, one of the woodcutters, galloped to Canoa with the news. Kirkland was there, preparing to help escort the last group of Pinal prisoners to Ewell at Aravaipa Canyon. He gave Childs a fresh horse and sent him on to Tucson to find Larcena’s distraught husband.

Although the Apaches had said his wife was dead, Page had not lost hope. Now the revived man was galloping south to Canoa with Childs, Tucson Dr. C.B. Hughes and Ed Radcliff of Tubac. They rode all night, reaching the ranch just as Kirkland was leaving. They pushed on the final dozen miles to the lumber camp and were stunned by what they found.

“What a sight,” Radcliff declared, “emaciated beyond description, her hands and knees and legs and arms a mass of raw flesh almost exposing the bones, caused by crawling over the cruel rocks, up hill and down hill.”

Doctor Hughes told Page he had no hope of saving Larcena.

Page would hear none of that. He commandeered a wagon and tenderly placed his wife into it. He and the doctor drove the team as carefully as possible along the rough mountain trail down Madera Canyon and then north on the rutted road to Tucson. Page wanted Larcena to be under the constant care of the doctor.

She clung precariously to life for several weeks, and then began a seemingly miraculous recovery. When Radcliff saw her again that summer, he recalled being amazed at the “blooming woman before me.”

The many scars slowly healed, at least those of the flesh. That summer, Page took his bride to the cabin he had built for her near the mouth of Madera Canyon, 10 miles from Kirkland’s Canoa ranch. There, they could begin life anew.

They did not know peace for long.

Terror and Tragedy

On January 27, 1861, Aravaipa raiders struck Johnny Ward’s ranch in the Sonoita Valley and kidnapped his 11-year-old stepson Felix.

Captain Ewell had departed for the East, and an inexperienced young lieutenant was sent in pursuit of the Apaches. He traveled to Apache Pass, where he confronted Chiricahua Chief Cochise about the lost boy.

When Cochise denied involvement, the soldiers seized several of his people as hostages. The chief escaped, and when the hostages were hanged, he began a bloody war of retribution.

Within 60 days of the incident at Apache Pass, the Apaches seemed to strike everywhere. Cochise’s warriors hit five stage stations, repeatedly attacked the mail coaches and swept through the Santa Cruz Valley, killing 150 of the hated White Eyes, including Poston’s brother. One of the first victims of the war was Larcena’s husband.

Wadsworth had hired Page and two other sawmill men, Alf Scott and Jim Cotton, to escort a supply wagon he needed delivered to Fort Breckenridge. A heavy snowfall that January disrupted work at the pinery, so Page saw the job as a nice opportunity to pick up extra cash. He needed the money, for Larcena was pregnant with their first child. Page bade a melancholy farewell and left her in their snug cabin at the mouth of Madera Canyon. He would be back soon.

On February 20, Page’s party was 30 miles north of Tucson. Two Hispanic men and a woman rode in the wagon while the three men scouted ahead. As they halted to water their horses along a wash in the Catalina Mountains, the Apaches struck.

Cotton turned toward his friends, only to see both of them slumped over their galloping horses. The Apaches’ shots spooked the oxen, who lurched forward and caused the wagon to tumble off the road and down into a steep ravine. As the Apaches rushed the overturned wagon and flailing oxen, Cotton and the three Hispanics beat a hasty retreat toward Tucson, which they reached about noon the next day.

Charles Brown, who operated Tucson’s premier saloon, attempted to raise a force to ride to the assistance of the two men, but the news from Apache Pass had unnerved the town’s bold frontiersmen. William S. Oury, who had just returned from Apache Pass, finally recruited three men to accompany them. Cotton guided the party back to the canyon.

At dawn, the call of the scavenger birds led them to Page. His dead body lay in a mesquite thicket several hundred yards from the wagon. His horse, with its throat cut, lay beside him. Scott’s saddle, pistol and blanket were also there. The wounded men had fought off the Apaches for at least a day before Scott tried to leave and secure help. The men had killed the horse to drink its blood.

They buried Page where they found him and, two weeks later, another party discovered Scott’s mutilated body. Oury took Page’s kerchief, pocketbook and a lock of his hair to give to Larcena.

Elias took his daughter Larcena to the big stone house on his border farm along the Santa Cruz so that her sisters could look after her. In September, Larcena bore a daughter who she named Mary.

In time, the Apaches came to kill Larcena’s father and two of her brothers. A young woman of deep religious conviction, Larcena bore all her tribulations with grace, but often remarked over and over: “God is good, and knows best…God is good, and knows best.”

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society 13751 –

Paul Andrew Hutton researched Larcena Pennington while writing The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History, published by Crown in May 2016. He has published 10 books and teaches history at the University of New Mexico.