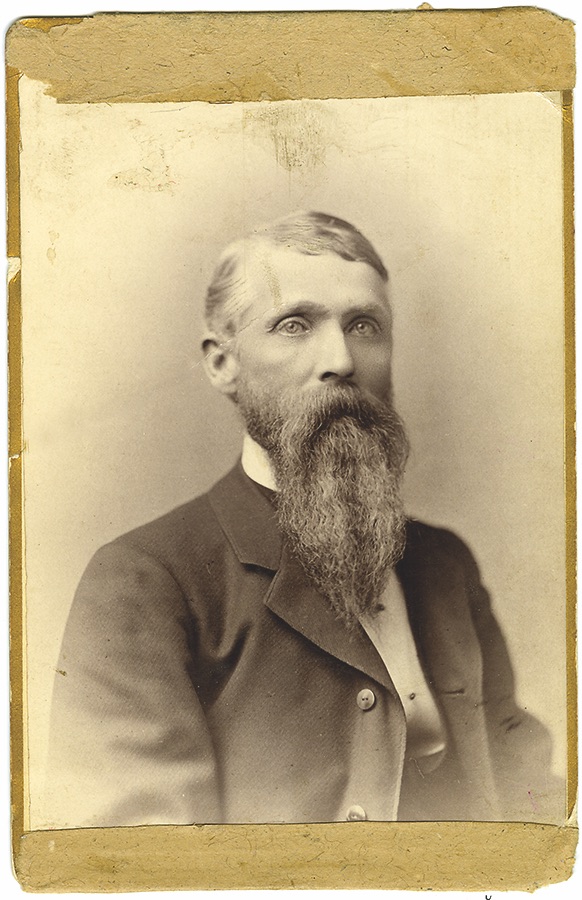

Two Kansas City boys hiked the famous road west in 1874 to make their mark in the cattle trade.

– Courtesy of The Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, X-19367 –

The Santa Fe Trail, a vital commercial route, developed international trade between the United States and Mexico, fostered commerce on the Plains, served as a military road and contributed to westward expansion in the United States. William Becknell and five men, desiring a profitable outcome, began a momentous journey September 1, 1821, from Franklin, Missouri, and in November reached Santa Fe in what was then northern Mexico. Becknell’s venture was lucrative, and commerce significantly increased along the Santa Fe Trail, which evolved and divided into the Cimarron and Mountain Routes. Many smaller feeder routes arose from the wagon ruts left alongside strategic waterways, one being the Arkansas River that flowed across the Plains.

In 1874 the Santa Fe Trail fervently beckoned Albert F. and Leander A. (Lee) Mosty as they responded to the West’s wild call. Before them had come William Bent and John Wesley Prowers, who had heightened commerce on the trail in earlier decades.

In the early 1830s, Bent, St. Vrain & Company built Bent’s Fort, or William’s Fort, on the United States side of the Arkansas River in what is now southeastern Colorado. Ceran St. Vrain and brothers Charles and William Bent were partners, as indicated in a January 6, 1831, letter from St. Vrain to Bernard Pratte & Company. Generating much trade among trappers, fur traders, explorers and Plains tribes, Bent’s Fort began operating around 1833. The Cheyenne and Arapaho were regulars. The fort became a major trading destination on the Santa Fe Trail. By 1849 Bent, St. Vrain & Company had dissolved, leaving William the sole owner of Bent’s Fort.

Sometime between August 16 and 21, 1849, William blew up his trading post. Cholera outbreaks, broken negotiations for the sale of the fort to the U.S. Army, or a rumor that the military was going to confiscate the fort possibly motivated Bent. Enough structure remained within the ruins for a stagecoach station to emerge a decade later, but by the early 1880s, the old fort served as cattle corrals, emphasizing the cattle industry’s marked development.

Bent built a new trading stockade at Big Timbers during the 1850s in the Lower Arkansas River Valley where the Cheyenne and Arapaho traditionally wintered. This area was part of the Mountain Route. Just west of Bent’s New Fort, the U.S. government built Fort Wise, later renamed Fort Lyon, which operated from 1860 to 1867. The government also leased Bent’s New Fort. After a severe flood damaged Fort Lyon in 1866, the second Fort Lyon was built near Las Animas in 1867, which the U.S. Army first occupied in 1868. Any viable government fort required livestock and produce, and Prowers filled those needs.

Prowers worked for Bent from 1856 to 1863 and regularly used the Santa Fe Trail to lead supply wagons from Missouri to Bent’s New Fort and Fort Union, New Mexico Territory. Prowers brought cattle west in 1861. After leaving Bent, Prowers worked as a sutler at Fort Lyon, and from 1865 to 1871 freighted government supplies between Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and Fort Union. He bought land, increased his cattle herd and oversaw his farming. By 1873 he was a partner in Prowers and Hough, a busy commission house in West Las Animas.

When Albert and Lee Mosty answered the West’s siren call during the spring of 1874, the two knew the Santa Fe Trail was an important route. Lee, almost 23, and Albert, only 19, made a pact: “We will hike off into the great West and grow up with the country. We will remain together, we will stick together like wax, we will never part.”

Lee resigned from J.E. Forbes & Company Hardware in Kansas City. Albert quit the Olathe Rolling Flour Mill in nearby Olathe. Albert wrote and sketched in his monthly journals throughout the journey and the remainder of 1874.

Before heading west Albert purchased a sombrero. Peacock proud, he strutted and waited for Lee at a railroad depot in Kansas City. “Some of the policemen didn’t like the looks of me… my hat signified business, while Lee was there one old bugger came up and rapped me with his billy,” Albert wrote.

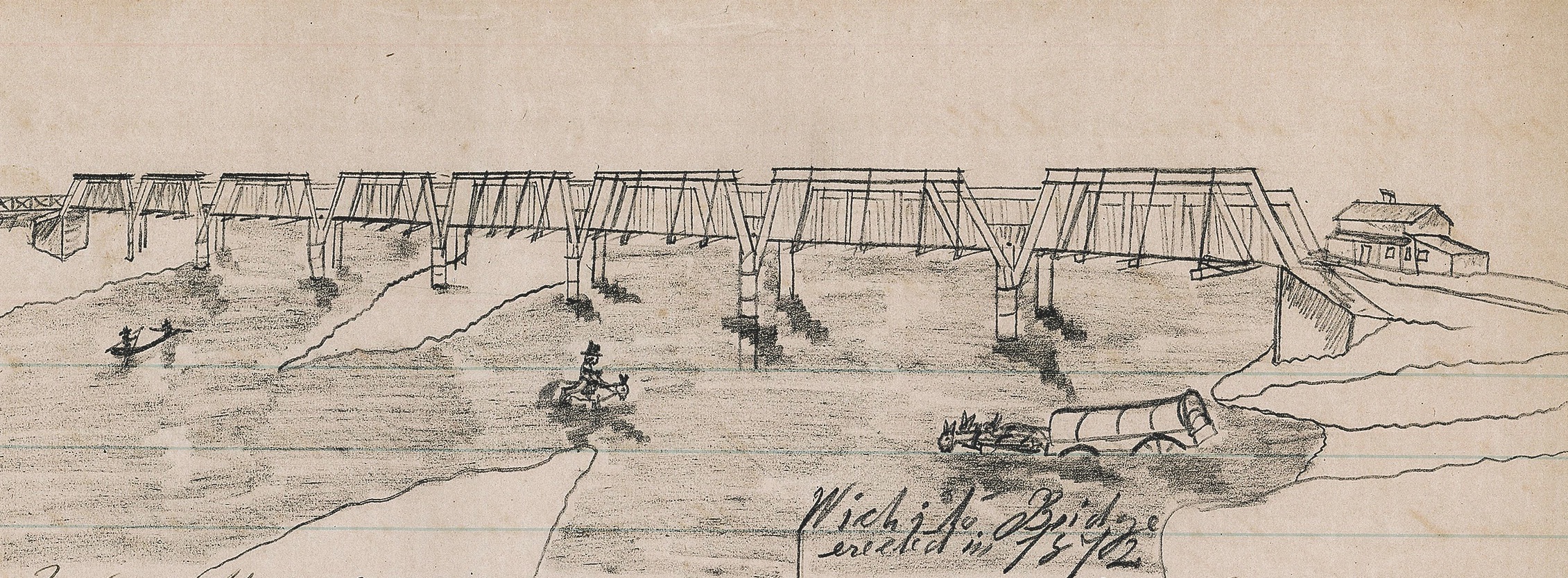

The momentous adventure began. Albert and Lee visited older brother Frank in Butler County, Kansas, and then traveled to Wichita, a cowtown. From there they tirelessly hiked northwest along the Arkansas River and then west behind the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad (AT&SF) tracks in Kansas, which roughly followed alongside the Santa Fe Trail.

During a late afternoon in May, Albert and Lee perched on a fence by the AT&SF Depot in Great Bend, Kansas. Two men walked up from the Arkansas River and into the depot. A third man approached the brothers and sat on the fence. “I saw a howling John, sticking out behind, when the two men came out of the depot and went down the steps of the sidewalk,” Albert wrote. The man on the fence jumped down and yelled, “Stop!”

The two men turned around. “What do you want?” one asked.

“You swindled me out of ten dollars!”

“Liar!” the two men responded.

“Lay down that money! Lay it down on the sidewalk. Lay it down, right down!”

“Go to hell!” one of the accused shouted.

Albert recorded the gunslinger’s actions:

“…so he aimed and shot, the fellows got a good start before he got a shot—they ran a good ways past, he shot at one Then at the other, he shot one in the body and arm and the big fellow in the leg and foot…the big fellow when he was hit in the leg, fumbled away and looked around several times and then got underway again…they had been gambling, after the man got done shooting he walked around the depot reloading his pistle…”

– Courtesy of History Colorado-Denver, Colorado –

The gunslinger briefly searched for the wounded men but returned alone. He then galloped his horse swiftly through town, fired his pistol into the air, and yelled “like the devil,” Albert wrote. The gunman “wanted to let folks know he wasn’t afraid of the whole town.”

Upon reaching the AT&SF terminus in Grenada, southeastern Colorado Territory, in late May, Albert and Lee hiked the Santa Fe Trail’s Mountain Route. The brothers walked 15 miles and entered a cowboy camp where friendly cowboys offered them “good bread, good coffee, and good buffalo steak.” The brothers spent a night at the welcoming camp, continued their journey, and reached “the most beautiful valley on the Arkansas River. There were groves of trees…then more trees and more trees,” Albert wrote. Unbeknownst to the brothers, they had begun walking through Big Timbers, an area with massive cottonwood trees and valleys, on the Santa Fe Trail. To the west lay Las Animas.

– Courtesy of History Colorado-Denver, Colorado –

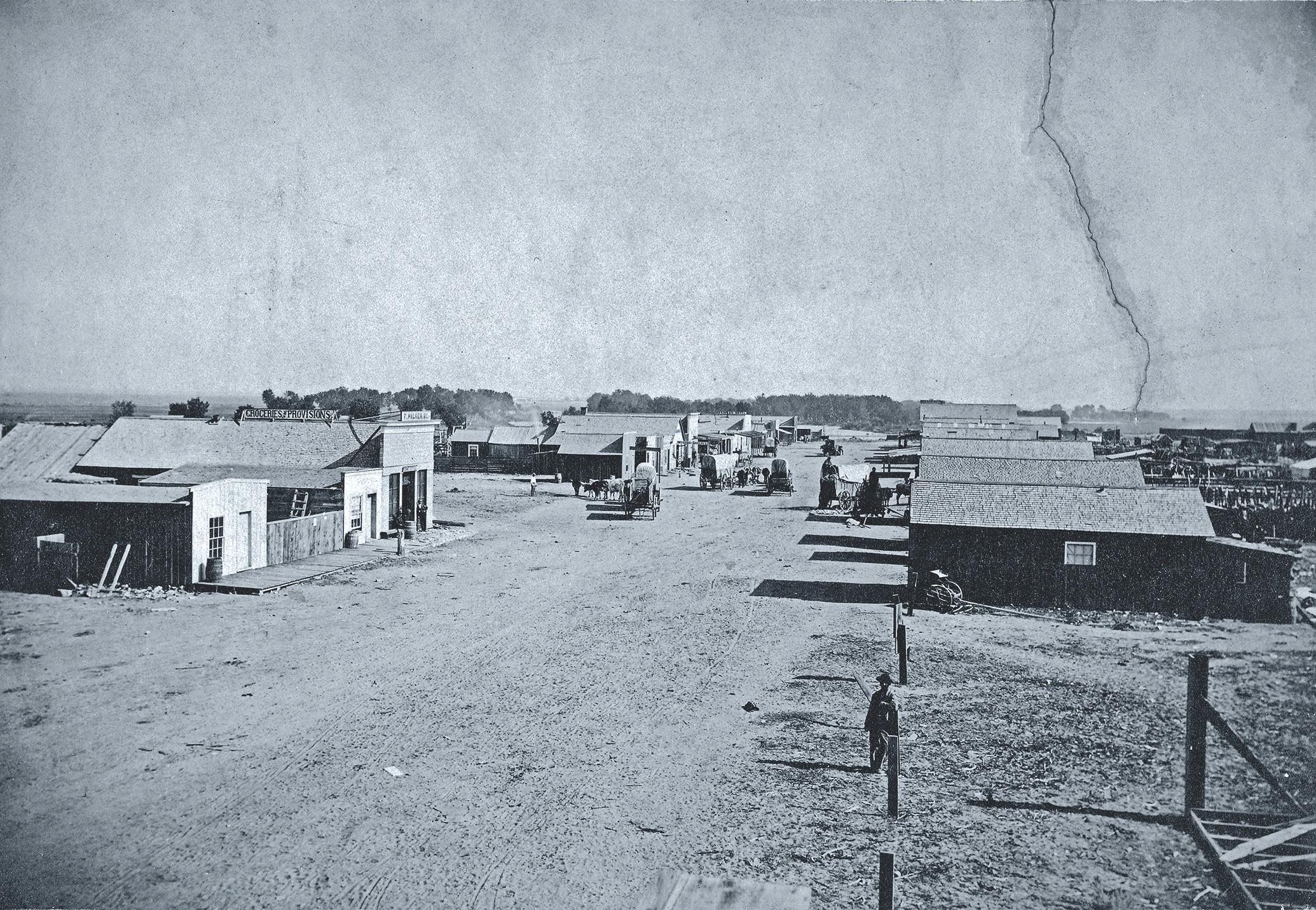

The brothers reached Las Animas, not to be confused with newer West Las Animas. Capricious chance intervened. Albert and Lee bought goods in McMurray Brothers General Store and met Nick Eaton, a stockman from nearby Mud Creek. Eaton needed a seasoned cook and additional drovers to help him drive Texas cattle north. The brothers asked to work for him, but Eaton said he would only hire one greenhorn and left.

“He would give only one of us a job. That let us out, we would not part,” Albert remembered thinking.

Albert was wrong. The next day Lee headed north with Eaton and the Texas cattle. Lee regularly drove large herds of cattle up the trails from Texas to Kansas for Eaton before becoming an independent cattle buyer and trader. Lee died in 1917.

What about Albert?

Prowers, now an influential and wealthy stockman, trader, merchant and an 1873 Territorial legislator, hired Albert one day after Lee’s departure. Albert would become a cowboy and later a foreman for the large Prowers Ranch, which had cattle, horses and sheep. With John Carter as head foreman, cowboys in designated camps worked the vast range.

While settling into his new life on the Prowers Ranch in June 1874, Albert herded a large flock of sheep on the bluffs near the Johnson Ranch at Caddoa, about 20 miles east of Las Animas. He recorded that he had killed a big snake and seen a coyote and a black eagle. “The sheep herded like race horses…guess they traveled as far as ten miles, I couldn’t stop them no way,” the astonished youth wrote.

– From the Albert Mosty Collection of The Bryan Museum. Galveston, Texas –

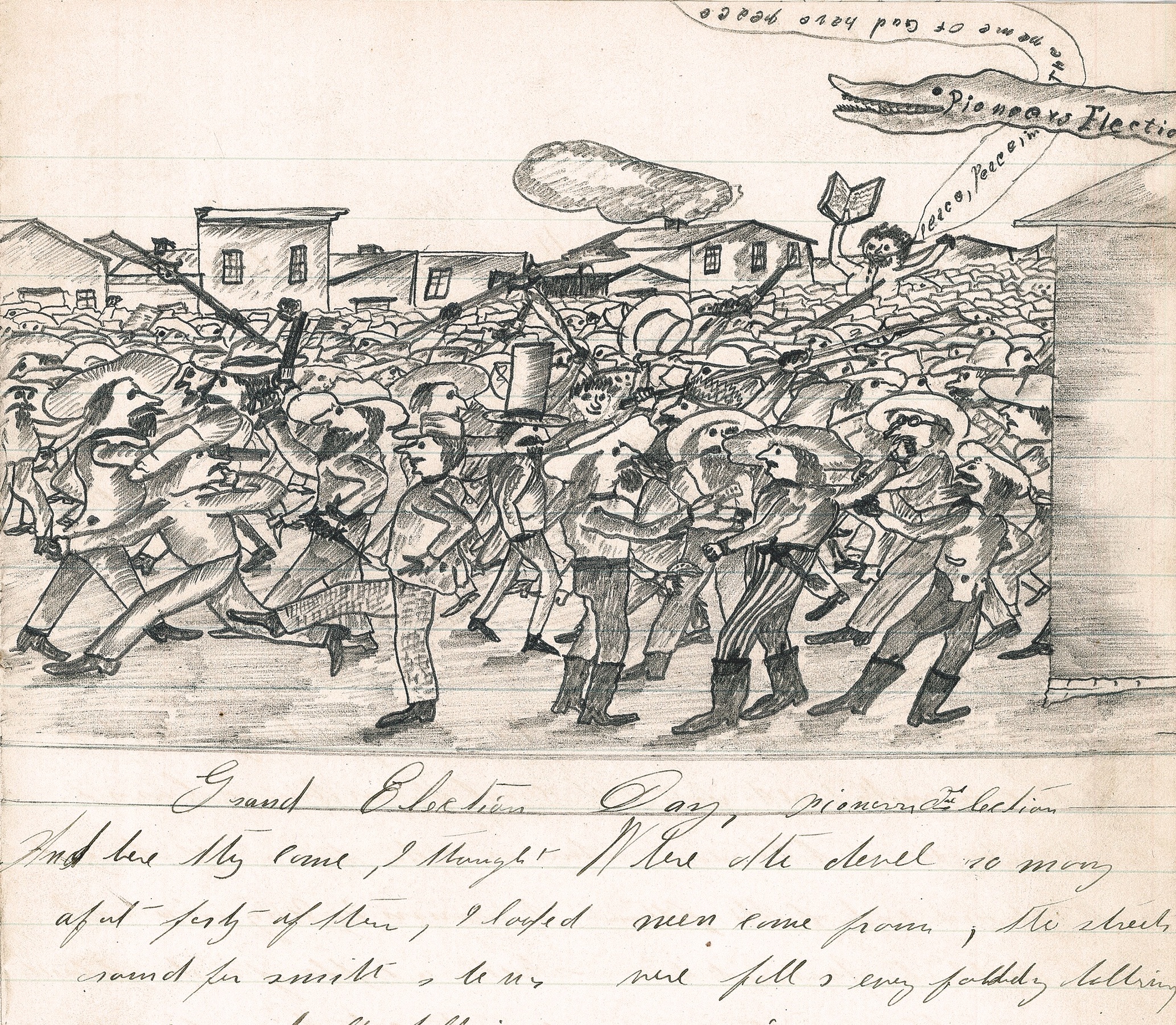

Albert’s August 1874 journal referred to Grand Election Day’s disorderly activities in Bent County. Men known as Smith and Mexican John had accompanied Albert to Las Animas, having been elected county seat again in 1872. Albert indicated the three were besieged by political hucksters:

“And here they came, I thought about forty of them, I looked around for Smith and he was gone, and all… all hollering here…here is your ticket and every one that could get hold of me was pulling at me to come his way, every one was electioneering for himself or some boddy else, it seemed, all after me, I wondred Where the devel so many men came from, the streets were full, every boddy hollring, some going one way and some another way, some fighting—here came Mexican John with his knife out and sleeves rolled up to the elbow and ready for fight…”

– Courtesy of History Colorado-Denver, Colorado –

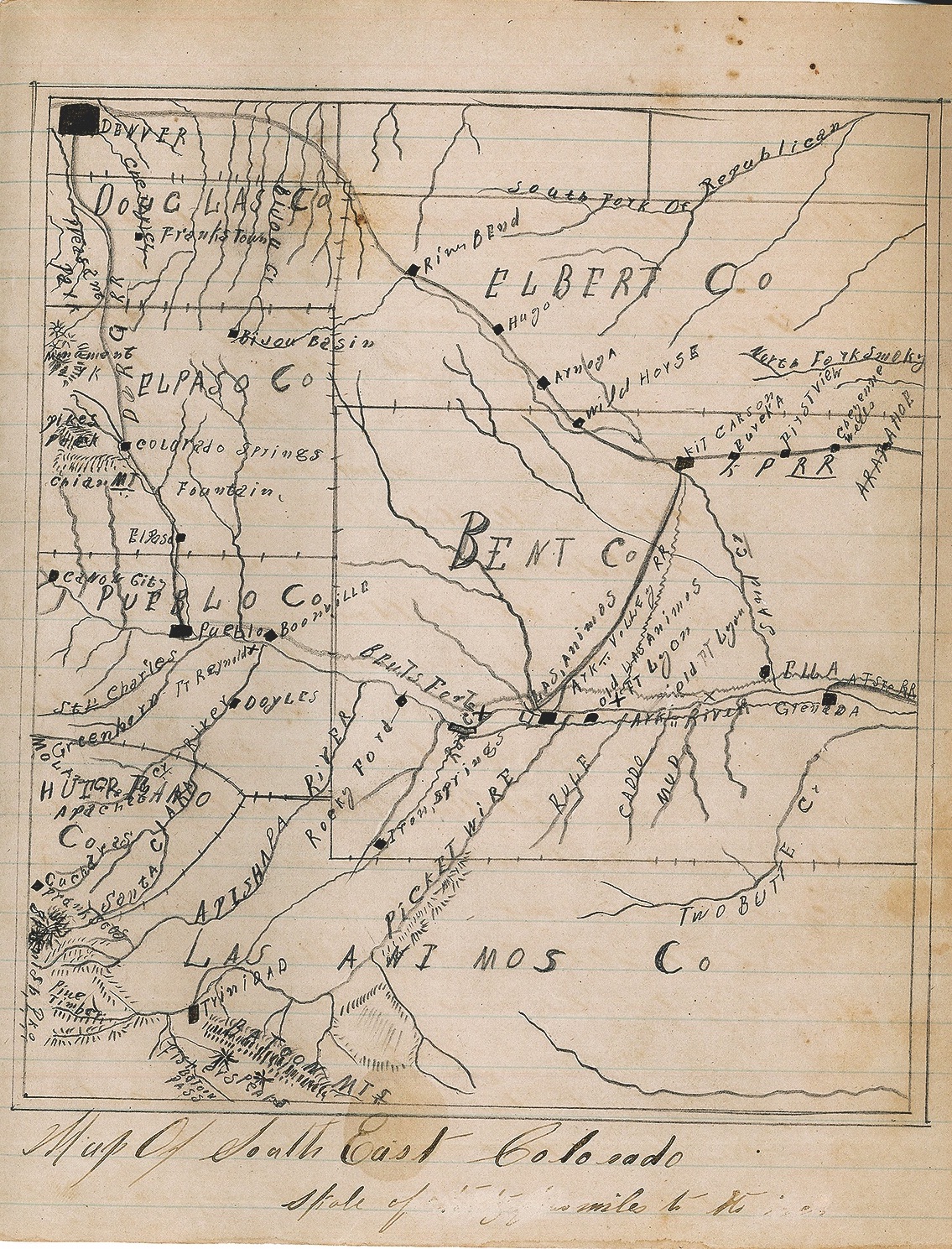

Albert continued illustrating his journals. In September Albert sketched the Prowers Ranch, located 12 miles below Fort Lyon, in October Bent’s Fort, and in November Old Fort Lyon. In early 1875 his two-page map of Bent County depicted rivers, creeks, ranches, towns and forts.

By 1875 the cattle industry boomed in the Lower Arkansas River Valley. Partners Charles Goodnight, John Hough and Prowers established a slaughterhouse in West Las Animas that year. Goodnight later ranched in the Texas Panhandle.

– From the Albert Mosty Collection of The Bryan Museum. Galveston, Texas –

Prowers depended upon Albert. Due to the ranch’s great size and available mailing posts, Prowers wrote Albert a letter on September 2, 1876, requesting him to gather wayward cattle wandering near Kiowa, Elbert County:

“I think you and one of the Boys had better come to Jones camp & there 2 of his men will come along with you & drive back every thing south of Kiowa, I think the best thing would be to come to Kiowa & hunt this way & gather everything & drive back, & when that is done come on toward the river driving what scattering ones you find & when you get here we will rig up an outfit & make a drive back… Let me know how the cattle are doing write me what you think of the prospects of holding them—do they try to go up or down the creek.”

Albert visited family for Christmas in Kansas City in 1880 and received a letter from Prowers dated December 20. Adverse weather conditions had caused livestock deaths on the ranch’s northern boundary:

“Boys are picking up a few steers & calves on the north side. They went down yesterday but to day I hear the snow is 12 inches deep… I don’t think the boys can do anything but take care of the Horses. We lost 2 Head. The white pony 70 that Clif rode & the Bay Hosa [Little Raven] horse that Carter rode this summer. Also 1 mare on the range, I lost 12 saddle Horses from mares. [Malloy] lost 5 Horses and a lot of stock horses has died on Jones range.”

This is how the settlement looked when Albert and Lee Mosty arrived via the Santa Fe Trail and first met Nick Eaton, stockman, at McMurray Brothers General Store.

– Courtesy of History Colorado-Denver, Colorado –

By 1884 Prowers owned vast ranchlands and farmland. During one autumn count, his cattle herd had numbered around 70,000. Sadly, Albert’s benefactor, only 46, died February 14, 1884. Albert worked for Prowers or Prowers’ business managers for almost 15 years and then farmed in Macon, Missouri, where he died in 1931.

The Mosty brothers had answered when the West called and the Santa Fe Trail beckoned. Bent and Prowers had promoted a supply network for those who came after them along the Santa Fe Trail.

Kenyon Bennett grew up on ranches in Lampasas County, Texas, and writes about Old West history. Her current long-term projects focus on cattle drives and a circuit-riding preacher from Lampasas County. She is the features coordinator and journalist for two newspapers in southwestern Wisconsin.

– Courtesy of University of Southern California Libraries and California Historical Society –