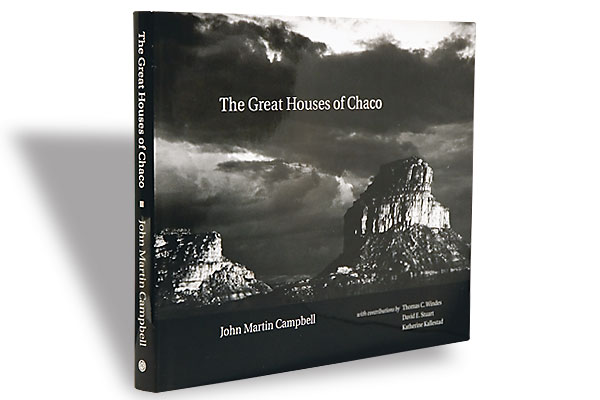

Scholars and archaeologists may debate why the great Pueblo Indian society existed in Chaco Canyon, but everybody agrees on one thing: It’s in the middle of flippin’ nowhere.

You don’t just happen to go to Chaco Culture National Historical Park in northwestern New Mexico. This isn’t Salmon Ruins near Bloomfield, or Aztec Ruins National Monument in Aztec, or even Mesa Verde National Park near Cortez, Colorado, all places you can swing into if you’ve half a mind and are in the area.

No, to get to Chaco, you’ve got to be going there. Twenty-plus miles from U.S.550, and much of that on a rough, dust-choking dirt road. Blistering hot in the summer. Bitterly cold in the winter. Unpredictable in spring or fall. You know the trip is not for the weak-kneed when park rangers warn about hypothermia and flash floods.

Yet for those interested in ancient Puebloan culture, Chaco is monumental. The park is home to almost 4,000 archaeological sites.

The most-asked question—other than, “When will you pave the roads?”—is “Why?” Why…why…why did this place exist?

For some 300 years, beginning in the mid-800s, Chaco rocked. That is, until the canyon lost its significance and people began abandoning the place, perhaps because of drought or maybe they just wanted to be closer to a city with one-hour martinizing.

Ah, but during those centuries, Chaco reined supreme. The great houses of Pueblo Bonito, Una Vida and Peñasco Blanco were built, and others followed. They were kind of like all those apartment complexes you’ll find in Arlington, Texas. But unlike those suburban blights, Chaco was an architectural wonder.

Most buildings were built to solar, lunar and cardinal directions, the park ranger tells me and a few other hearty tourists. Astronomical markers were quite sophisticated, we’re told. Sunrise equinox programs are held at Casa Rinconada. The building is aligned with the equinox sunrise.

The ranger recommends that we return in December to join him for the winter solstice sunrise program at Pueblo Bonito. Temperatures will be in the teens, even lower? Maybe snowing? I pass.

Chaco’s Great Houses were connected by a sophisticated road system to more than 150 other Great Houses across the Southwest.

“Why?” we ask.

“Ah,” the ranger says with a sigh. “We don’t really know.”

The place had to be more than a farming region. Was it built for trade? Archaeologists believe that by A.D. 1050 Chaco had become the center of the San Juan River Basin—ceremonially, administratively and economically.

Was it built as a great social experiment? A trading center? A religious hub?

“We may never know,” the ranger says to us.

Those questions stay with me as I leave Chaco, bouncing along dirt roads for what seems an eternity, choking on dust and passing no cars until I hit U.S.550. Why…why…why?

The next day, a theory strikes me. A massive complex rises out of the desert landscape, reminding me of Pueblo Bonito, Peñasco Blanco and those other sites I had marveled over. The sign tells me I am approaching Buffalo Thunder, and the parking lot is filled with cars.

Could that be an answer to the mystery? Was Chaco a mix of social experiment, trading center and religious hub? Was Chaco Canyon…a casino?

I probably should have kept that thought to myself. Now I’ll be banned from Chaco Culture National Historical Park forever.