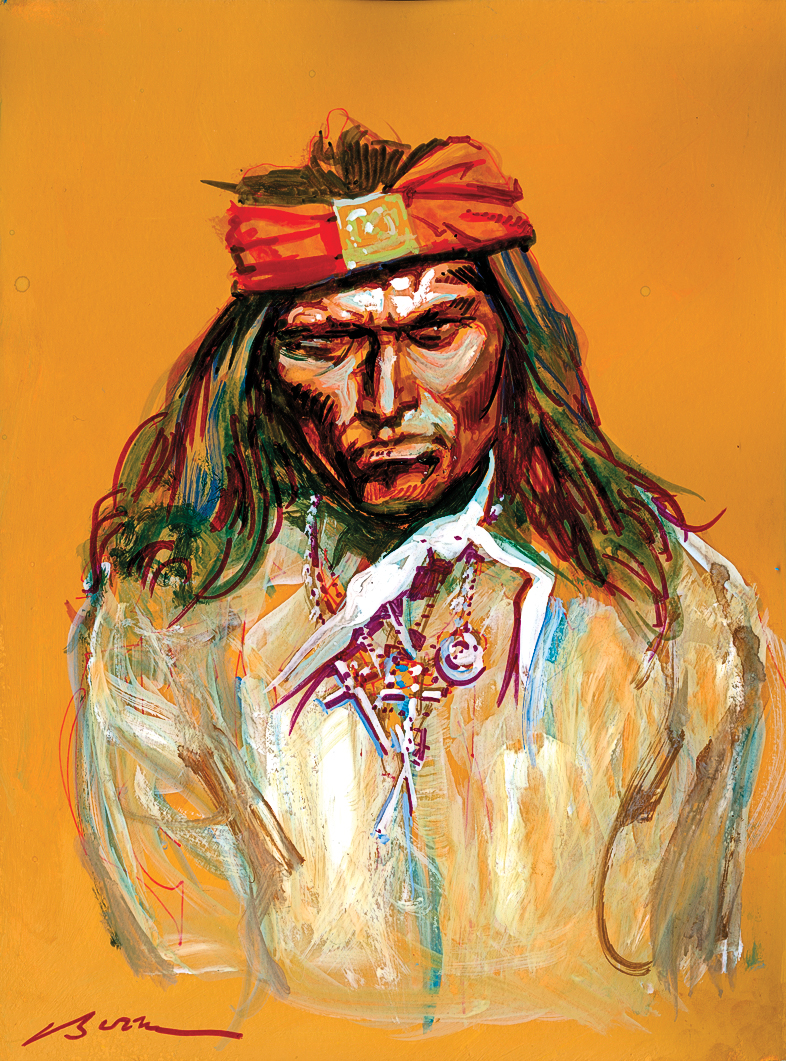

– Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

June 1, 1887

“The Indians know by motions. We know by signs.

Antonio reached out his hand and made a circle in his hand and spoke in Apache at the same time. He said that the five scouts will be sent down to the islands.”

—Chief Gonshayee, an eyewitness to the fight, who testifies that Antonio Diaz’s sign conveyed to the Indians that the scouts would be sent to Alcatraz or Florida, which triggers the shootout.

changes the Apache Kid’s life.

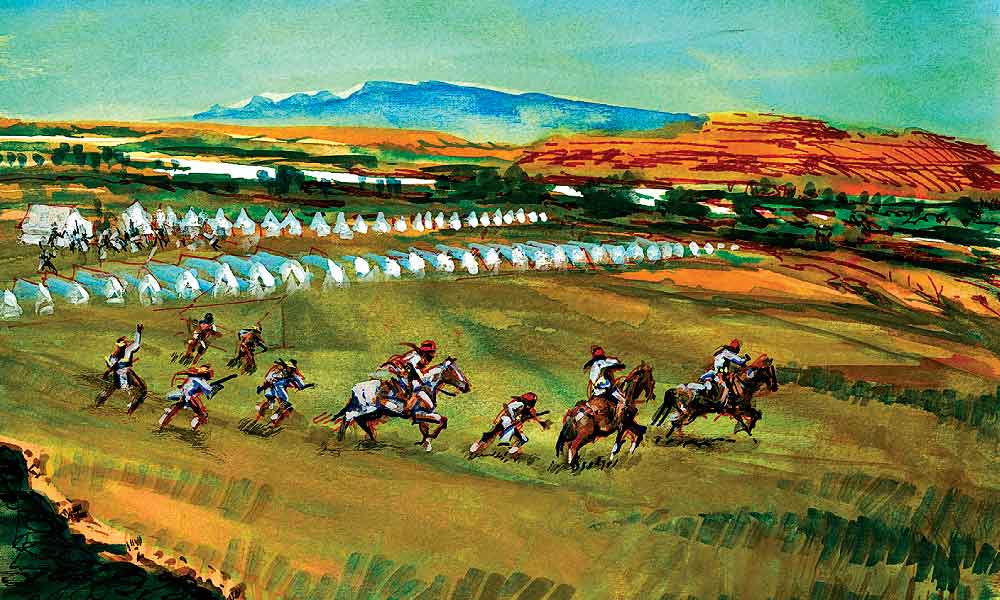

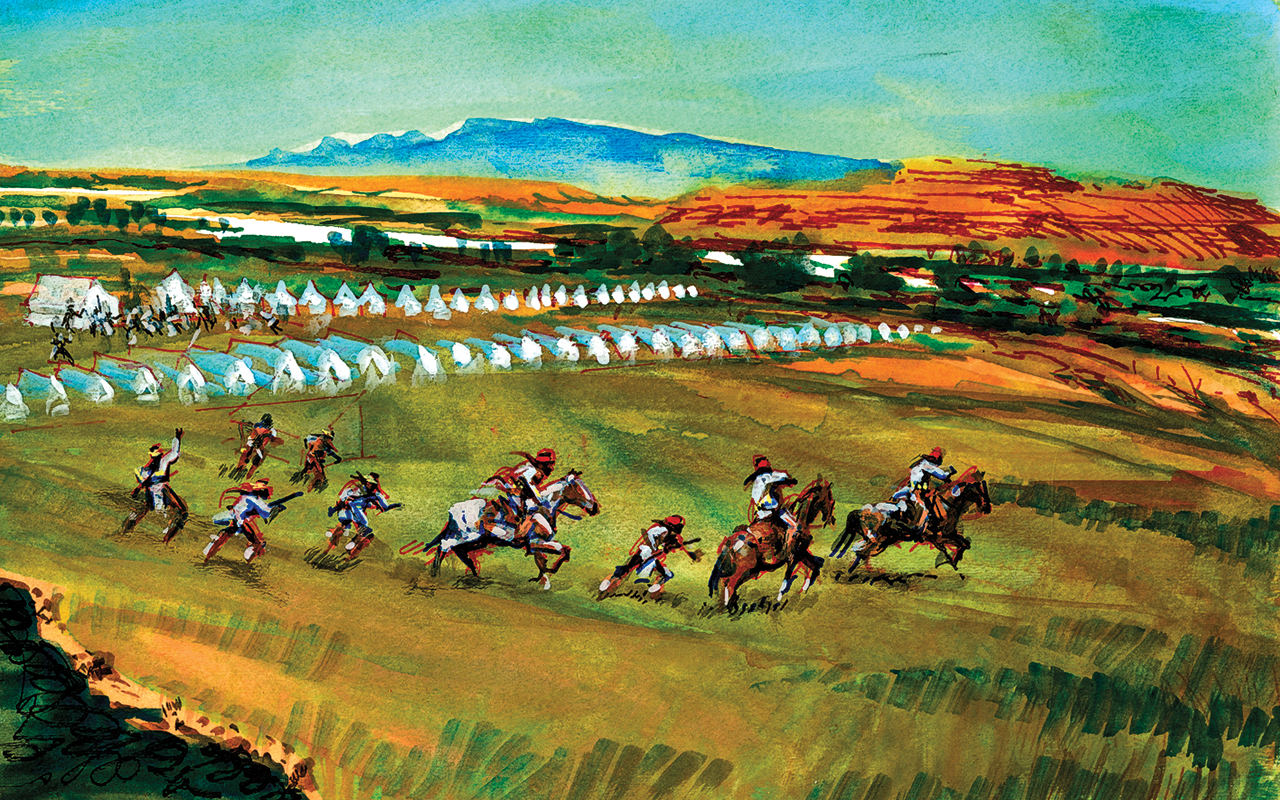

Absent from military duty for five days, the Apache Kid, along with four other Apache scouts under his command, ride single file into the Arizona headquarters of the San Carlos Reservation. The Kid was acting chief of scouts while Al Sieber was away at Fort Apache and the White River Subagency.

Upon his return to San Carlos, Sieber has summoned the Kid after hearing he killed another Apache in an alcohol-fueled family feud.

Told by a messenger that the Kid wants to powwow, Sieber contacts the commanding officer, Capt. Francis Pierce; two interpreters are also notified. The clock is approaching 5 p.m. as Sieber and Pierce proceed 75 yards on foot, from headquarters to Sieber’s tent, to meet the party.

Although the Kid and his men are carrying their arms openly, in direct violation of camp regulations, none of the men in Sieber’s party is armed. As word of the scouts’ arrival spreads, other Apaches from the nearby camps gravitate toward the tent, and some of them are armed.

Walking up to the scouts, Sieber says, “Hello Kid.”

Returning the greeting, the Apache Kid and his scouts dismount, with their weapons in their hands.

Captain Pierce asks, “Where are the five scouts who have been absent?”

The Apache Kid and the others step forward.

“Give me your rifle,” Pierce orders the Kid. The Kid complies.

Pierce demands his gun belt, which the Kid surrenders. The captain places the rifle against Sieber’s tent and the gun belt in a chair. He orders the other four to give up their arms and gun belts, which they do.

Pointing in the direction of the guardhouse, Captain Pierce barks, “Calaboose!” (Spanglish for jail). Several of the Indians pick up their gun belts and remove their knife scabbards.

Pierce and Sieber hear an “unusual commotion.” They turn to see mounted Indians loading their rifles. (The assembled Apaches later claim one of the interpreters, Antonio Diaz,

had intimated, with Apache sign, that the arrested scouts would be sent to the “island,” which signified Alcatraz or even Florida; see quote on opposite page.)

Several of the disarmed scouts lunge for their weapons as Pierce jumps in between them, trying to shove their guns out of reach. The Kid makes a grab for his carbine, but Sieber grabs it with his right hand, while shoving the Kid with his left.

Unable to retrieve his weapon, the Kid runs around the tent and disappears.

“Look out, Sieber!” Pierce yells, “They are going to shoot!”

Sieber kicks the guns toward the tent as two shots ring out, one right after the other. Sieber and Pierce dive into the tent as bullets rip through the twin openings, from front to back.

Sieber grabs his weapon and runs out to engage the shooters. He fires at a mounted Apache who has just fired at him. But before Sieber can fire again, a .45-70 slug tears into his left leg below the knee, breaking the bone and knocking him flat. He crawls back into the tent as the Apaches disappear into the twilight.

The unexpected gunfight is over, but the long, tragic nightmare of the Apache Kid has just begun.

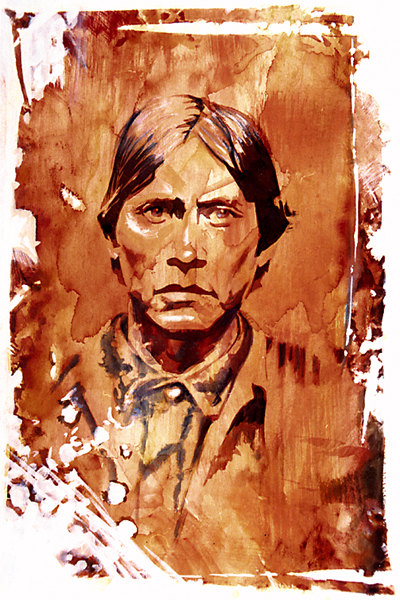

Al Sieber is crippled for life after his leg stops a .45-70 slug during the Apache Kid melee.

– All photos True West Archives –

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

On the run for 24 days, the Apache Kid surrenders and he’s found guilty and sentenced to death by firing squad, but Gen. Nelson Miles objects and intervenes, reducing the Kid’s sentence to 10 years at Alcatraz. After serving 16 months in the federal prison, the Kid is released on a technicality and returns to the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona. Soon, though, civilians led by Al Sieber press for new charges and the Kid is then sentenced to seven years at Yuma Territorial Prison. In transit and under guard, the Kid escapes and is never caught by the authorities.

Some historians believe that the Kid escaped into the Sierra Madre Mountains in Old Mexico where he lived out his life. Others believe he was killed in a shootout with Mormon settlers in Chihuahua in 1900 (see True West, February 2019 “Final Nail in the Apache Kid’s Coffin” by Lynda A. Sánchez).

In 1937, Norwegian explorer and anthropologist Helge Ingstad heard that renegade Apaches still lived in Mexico. Traveling deep into the Sierra Madre, Ingstad claimed he found a woman, Lupe, who was thought to be the daughter of the Apache Kid.

Recommended: The Apache Wars by Paul Andrew Hutton, published by Crown; The Apache Kid by Phyllis de la Garza, published by Westernlore Press.