Gary L. Roberts,

Doc Holliday Biographer

An emeritus professor of history at Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in Tifton, Georgia, Gary Roberts is a widely recognized historian of the American West. His works include Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend and Death Comes for the Chief Justice: The Slough-Rynerson Quarrel and Political Violence in New Mexico. His most recent volume, Massacre at Sand Creek: How Methodists Were Involved in an American Tragedy, was published by Abingdon Press in 2016.

If Doc were alive today, I would ask him about his family in Georgia. His relationships there—his doting and dying mother, his stern and distant father, his first cousin Mattie who he kept in touch with throughout his life and some say was his true love, his uncles and cousins and friends—shaped his character even before he went West.

My daddy always told me that the measure of a man is found in his character rather than his color, ethnicity, social class, financial condition or education.

It is a mistake to start a biography—or other form of history—by trying to prove that someone is a villain or a hero. Jesuit Father Francis Paul Prucha, a historian whose writings greatly influenced me, wrote that the historian must not care what the truth is. His only task is to find it. It is a whole lot easier to “prove” Doc, or any other Western figure, was a scoundrel or a hero than to find the truth. All you have to do is find sources that support your preconceived prejudice.

I wish I knew today what was in those letters from Doc that Sister Mary Melanie (Mattie) kept, what happened to letters that he wrote to other relatives and friends, what Zan Griffith, Lee Smith and other little known associates of Doc could have told me, and many other things that the absence of a real record forces me to speculate about.

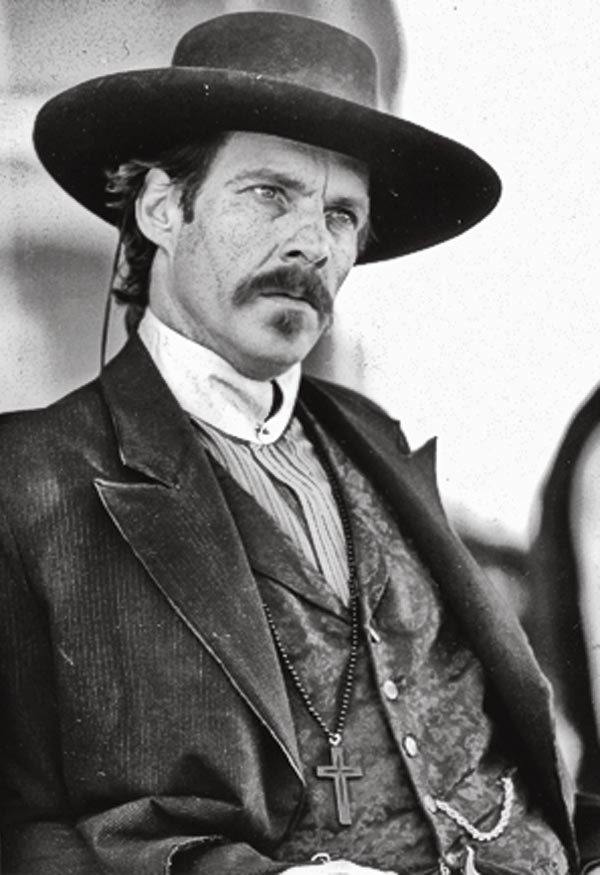

I first learned about Doc in TV Westerns (The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, Maverick and others) and in 1957’s The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, where Kirk Douglas’s Doc was more interesting than Burt Lancaster’s Wyatt Earp. My initial view of Doc was shaped more by Burns’s portrait of him in his Tombstone book.

The Doc myth that really grinds me is the persistent notion that Doc was a fatalist who wanted to die. I found him to be cynical and full of self-pity for more reasons than his consumption, but plenty of evidence showed he wanted to live, and to live with dignity. He developed a seemingly cavalier approach to danger, but that was more about survival than a death wish.

“I’m your huckleberry” was a common phrase in the 19th century, but no evidence shows Doc used it. It was attributed to him by Walter Noble Burns, in his 1927 book, Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest.

– Gary Roberts photo Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian; Holliday photo true west archives; Wyatt Earp photo courtesy Warner bros. –

Stories about Doc’s death are filled with misinformation. Neither Big Nose Kate nor Wyatt Earp were with him. Doc was not living in a sanitarium, but in a Glenwood Springs hotel in Colorado. In his last weeks of pain, pneumonia and delirium, he was taken care of primarily by two bellboys. His resources exhausted, gamblers and saloonkeepers helped pay his bills.

I’ve found no evidence before Burns’s Tombstone that Doc’s last words were, “This is funny.”

I am researching Doc’s largely unknown sojourn in Butte, Montana Territory, in 1885-86. An interview with Bat Masterson provided the clue to his visit there, and my follow-up research has uncovered a fascinating story of what might be called Doc’s “last hurrah.”

My next book will be a comprehensive study of the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864. This will be a culmination of more than 50 years of research into the characters, causes, controversies and consequences of a critical event in the history of American Indian-white relations. My hope is that it will also provide insight into the nature of violence and cultural conflict.