– Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

Douglas Magnus, the iconic silversmith in Santa Fe, New Mexico, shows me around the historic turquoise mines he owns in the nearby Cerrillos Hills. The mines aren’t commercially viable anymore, but if you look close, you might find semiprecious stones.

I pick one up and show it to Doug.

“That’s a very good stone,” he says, and slips it into his pocket.

Which, I guess, makes me a professional turquoise miner and adds me to a thousand years of history.

Magnus named his property, which includes the Tiffany mine, the Millennium Mines—not to cash in on the Y2K craze years ago but to honor “the thousand of years of history here.” After all, early Pueblo Indians mined turquoise here as early as 900 A.D.

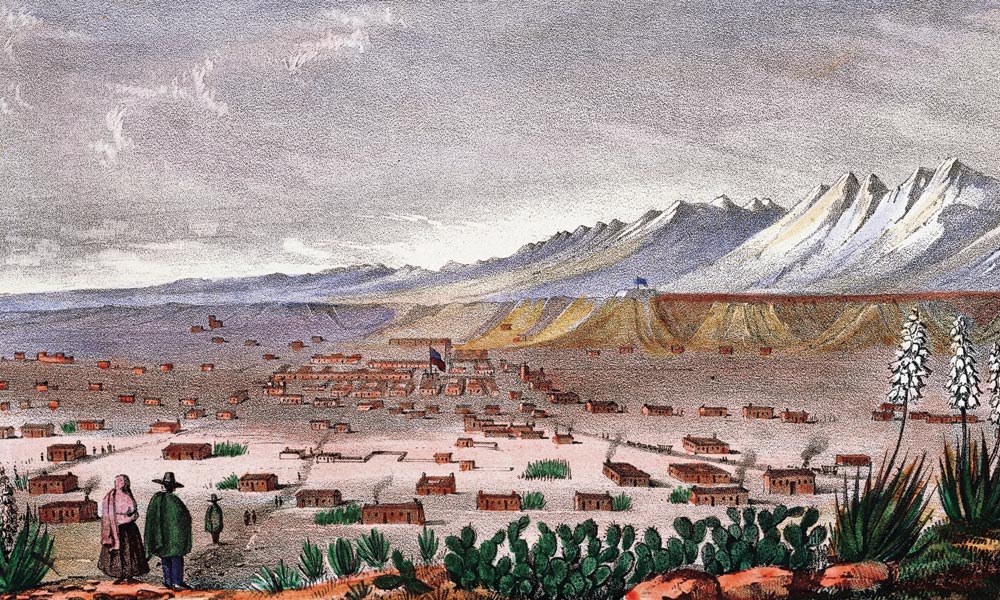

We’ll stick to the Wild West era along the Turquoise Trail National Scenic Byway, roughly 50 miles down state Highway 14 south of Santa Fe. There’s a lot of Western history packed into these 15,000 square miles before you head west to Albuquerque.

Stone Facts

The real turquoise boom began 125 years ago. In 1892, George F. Kunz, a geologist for New York-based Tiffany & Co., announced that turquoise of the “Tiffany Blue” color was now considered “gem quality.” That same year, James P. McNulty arrived in Cerrillos and went to work for the American Turquoise Company, which would sell some $2 million worth of stones to Tiffany to be turned into jewelry.

It helped that, for a while, one of the world’s oldest gemstones was thought to be found only in Persia, Egypt and New Mexico Territory.

Indians sold turquoise long before Tiffany.

In his diary entry of April 22, 1881, Lt. John G. Bourke (of On the Border with Crook fame) wrote: “A number of the young men from San[to] Domingo boarded our train to sell specimens of what they called ‘chalchuitl’ [actually chalchihuitl, from an Aztec word for green] (turquoise) of which I purchased three pieces. It is not genuine turquoise, but rather an impure malachite.… The real turquoise, however, is found in New Mexico and is held at an extravagant valuation by all the Indians of the South-West.”

For a history lesson, start at Santa Fe’s New Mexico History Museum. To see what turquoise looks like (and costs) today, visit the myriad shops on the plaza. Then follow Cerrillos Road south as it turns into Highway 14 and the Turquoise Trail.

– Courtesy USC Digital Library –

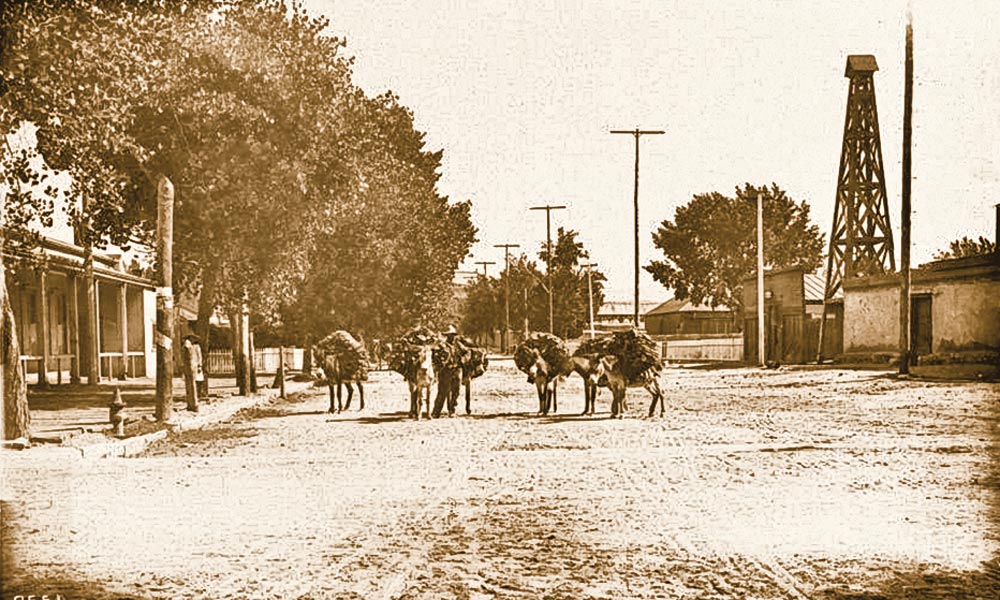

Dusty Cerrillos

The first town of consequence, loosely defined, is Cerrillos, which boomed in 1879 after two miners, unlucky in Leadville, Colorado, traveled south and found silver. Towns and mining camps sprang up. Territorial Governor Lew Wallace invested in a mine in the Cerrillos Hills, and later during a stay at the long-lost Carbonateville Hotel in Carbonateville, he proofed his novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.

Cerrillos might have disappeared, too, except the railroad arrived in 1881 and the turquoise boom began a decade later. In 1892, $175,000 worth of turquoise was mined in these hills. By 1896, that number was up to $475,000.

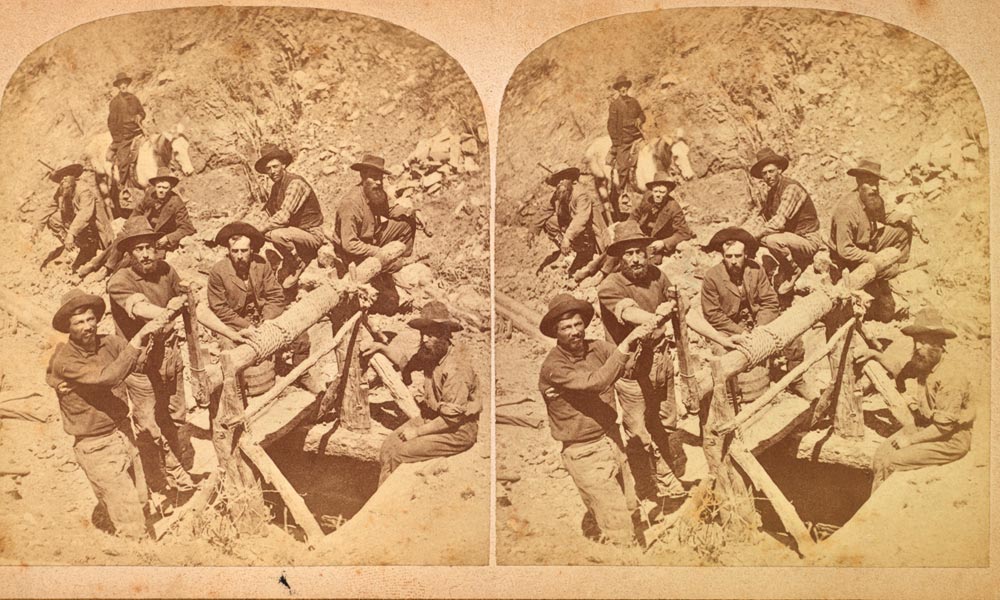

It wasn’t an easy way to make a living.

“Mining days averaged ten hours, from a little after sunrise to late in the day,” Patricia McGraw writes in Tiffany Blue. “The tools of the trade were dynamite, pickaxes, shovels, and lots of rope. Large, empty whiskey barrels stood next to the shafts, ready to be lowered down, filled with rock, and hauled up by the horse-driven whim, which was a pulley and gear system powered by a horse walking in a circle.”

If you were white, you earned $2.50 a day mining turquoise. Hispanics got only $1.50. Indians also got cheated.

– Courtesy New York Public Library –

As late as the early 1900s, Santo Domingo Indians, who had mined turquoise for years, approached area mines. Mine superinten-dent McNulty offered them second-rate turquoise, which the Indians refused. Tension eventually evolved into gunfire, arrests and

the sentencing of Santo Domingo “raiders” to hard labor at the territorial prison.

According to historian Marc Simmons, McNulty later conceded: “The Indians always thought they had a prior right to those old turquoise mines. And to be truthful, I had a hankerin’ notion they did, too.”

Cerrillos really boomed during the turquoise craze.

“We have all the saloons here we need,” the Cerrillos Rustler opined in 1894, “but a good stock of groceries and general merchandise is an absolute necessary.”

Don’t expect to find groceries today, either, but if you have guts, you can get a cold one at Mary’s Bar.

The discovery of turquoise in other Southwestern states, however, led to a decrease in prices. The market, and Cerrillos, crashed in the early 1900s. By the end of 1915, the American Turquoise Company was out of business in Cerrillos.

Turquoise didn’t bounce back until interest in Indian and Southwestern jewelry reignited during the 1970s. Cerrillos didn’t really bounce back, but it does have a trading post, state park, horseback riding company and a mining museum with, if you dare, a petting zoo. Today, Cerrillos might be best known as an old movie location. It doubled for Lincoln in Young Guns (1988).

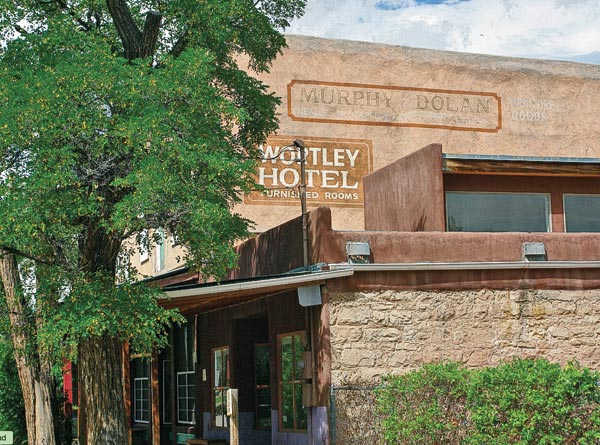

Funky Madrid

The Turquoise Trail, however, isn’t just about bluish-green stones.

Madrid, roughly three miles south of Cerrillos, first existed because of coal. Today it thrives off tourists, artists and society dropouts.

Coal had been mined since the 1830s, and the town started around 1869 (check out the Madrid Old Coal Town Museum). The new railroad needed coal, however, and Madrid boomed in the 1880s. Rivalries developed between Madrid and Cerrillos, including one between the Madrid Blues and Cerrillos’s Little Pittsburghs. Cerrillos’s baseball team was so bad, however, the manager ordered 3,000 sheets of flypaper to be placed on his players’ mitts.

Madrid went on to build a baseball park in the 1920s, reportedly the first west of the Mississippi with electric lights. Baseball, sometimes loosely speaking, is still played there.

– Photos by Johnny D. Boggs –

After World War II, coal prices dropped and, if you believe the stories, even lights designed by Thomas Edison and Babe Ruth swinging his bat couldn’t keep Madrid going. In 1954, the town was put up for sale. No offers came. By the 1970s, however, hippies, artists and people who wanted to disappear started turning Madrid from ghost town to art town.

A new rush began.

Golden Days

The first rush, however, came farther south near Golden. In the 1820s in the Ortiz Mountains, a man picked up a stone to throw at his mules. The stone’s weight caused him to stop and study it. It wasn’t turquoise or coal, but gold.

The town of Dolores, later called Old Placers, sprang up, but didn’t last long. Other deposits were found around 1840, and by 1880 mining companies were being developed. First known as El Real de San Francisco, Golden boasted 400 people in 1884.

That’s when journalist Charles Fletcher Lummis walked through on his way to Los Angeles. When Lummis left Cerrillos in December 1884, somebody told him he had a 12-mile walk to Golden. Three miles uphill, two other men told him he was now 14 miles from Golden but on the right road and heading in the right way. One-and-a-half miles later, he heard he had 16 miles to go. A hundred yards down the trail, he learned he was now 18 miles from Golden. He sat down. A bullwhacker came along and told him that Golden wasn’t quite 20 miles away.

After finally setting foot in Golden, Lummis wrote, “It is just 202⁄3 miles—I measured it that fateful afternoon. And mean miles they are….”

Today, it’s closer to 15 miles.

Golden must have looked like the City of Angels when he got there, for Lummis wrote: “This little camp has an 18-karat future before it.”

Just like the Sports Illustrated curse, Lummis’s words spelled the end of Golden. The population dropped, the mines went unworked, and about all you’ll find today are ruins, a store and the San Francisco de Assisi Church.

Into Duke City

The rest of the drive takes you to more civilized tourist stops in San Antonio/Sandia Park, Cedar Crest and Tijeras. Then head to Albuquerque, where the Turquoise Museum offers 90-minute guided tours (11 a.m. and 1 p.m. Monday-Saturday).

I recommend the chile rellenos at Loyola’s Family Restaurant, too. Green if you’re not sick of turquoise by then. Red, if you are.

Johnny D. Boggs enjoys the roast beef burrito at the San Marcos Café, Dennis Hogan jewelry at Ortega’s on the Plaza and listening to Doug Magnus’s stories.