The 1832 battle set the stage for the Texas Revolution.

The names are spoken with reverence in Texas: The Alamo. Goliad. San Jacinto. The great battles of the Texas Revolution, a conflict that lasted just under seven months. But the seeds of the war were planted years before that; the first real bloodshed came in June 1832.

Mexico was in the middle of one of its myriad civil wars. That made military officials in the northern provinces, specifically Texas, very nervous. They feared the Texians would take advantage of the disorder to seek independence for the region. To head things off, the officials arrested a number of potential revolutionaries, including William Barret Travis, who would later command The Alamo.

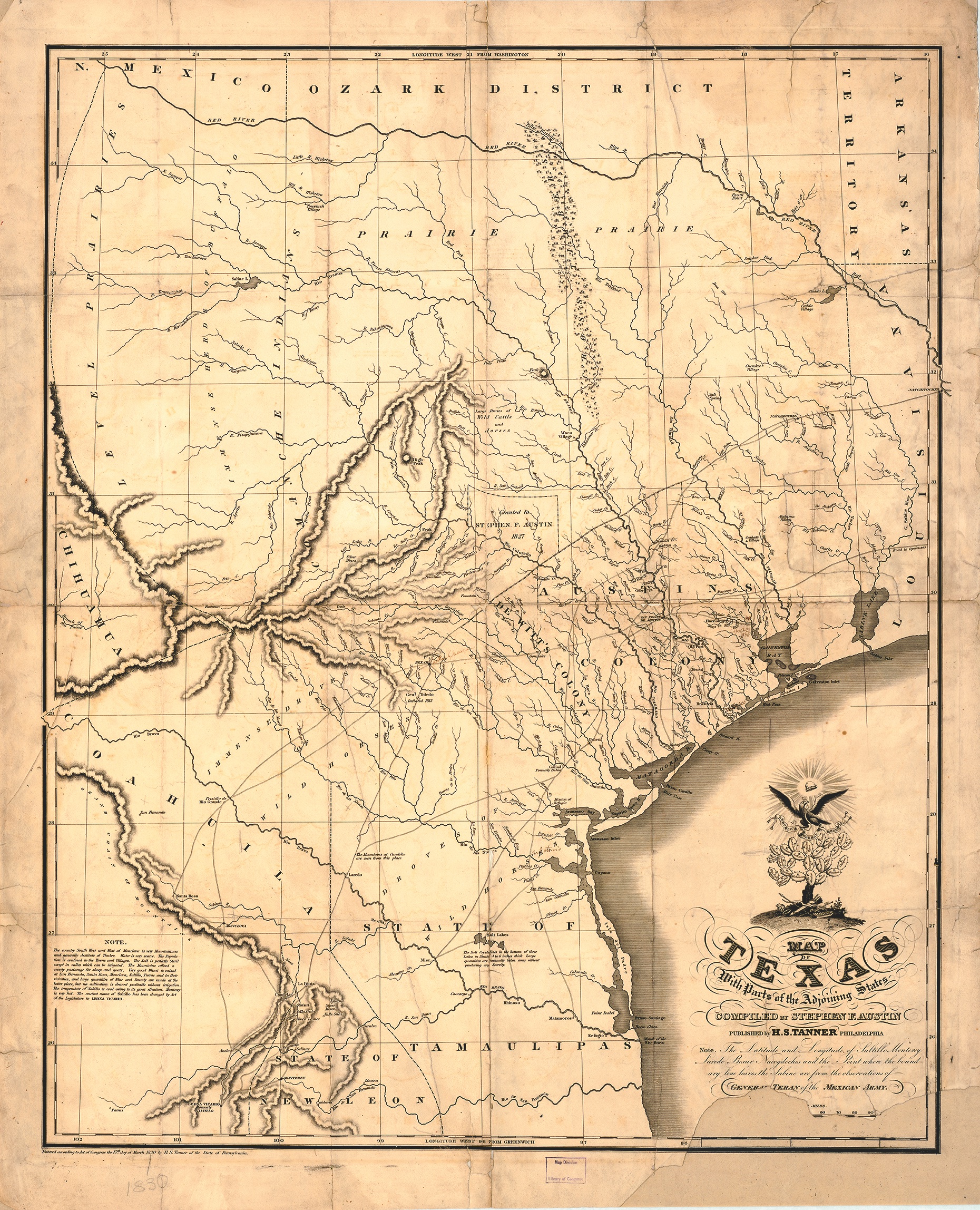

This arrest just served to anger the Texians. By early June, about 150 militia had gathered at Brazoria, along the Brazos River in southeast Texas, determined to free the captives. Secondarily, the Texians hoped the action would show support for rebel Gen. Santa Anna (a large irony there).

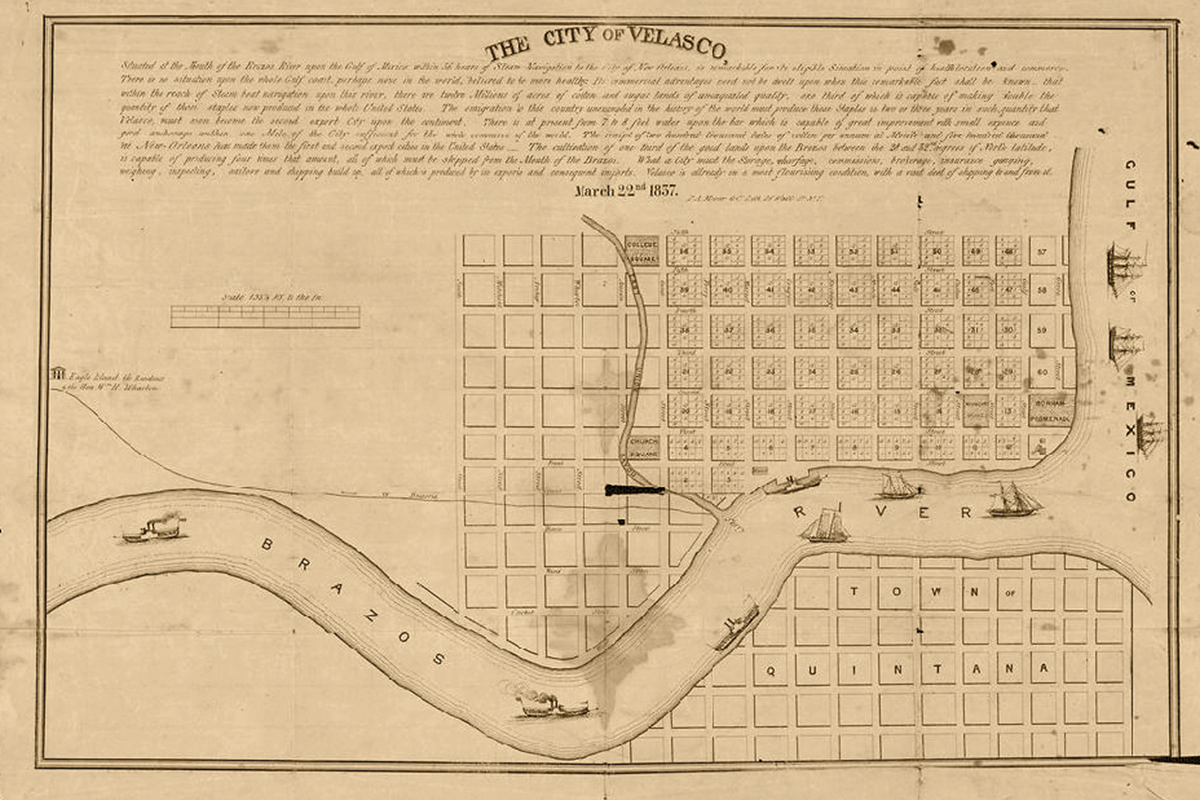

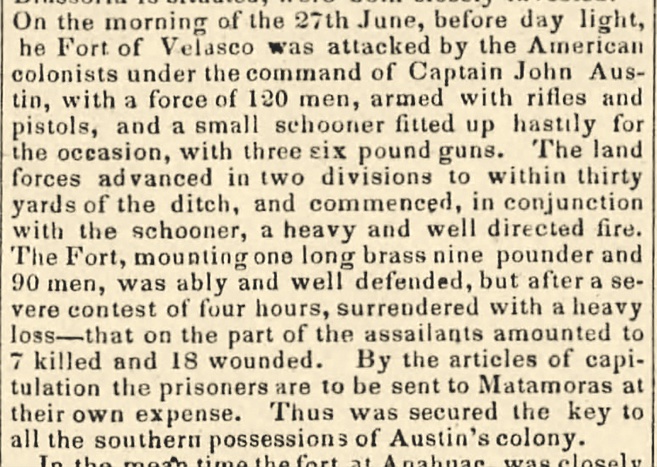

On June 22, the troops, led by John Austin (no relation to Stephen F.), began moving the 25 miles to Fort Velasco—some 40 men aboard a ship carrying a cannon, and the rest overland. The Texian forces, including the ship, covered three sides of the fort. Just before midnight, they attacked.

Most of the fighting was done at a distance, with the Texians unable to breech the walls of the fort and the Mexicans failing to take over the ship or disable the cannon. Sharpshooters did most of the damage for both sides. Heavy firing continued throughout the night. As dawn broke, rain erupted, dousing all the participants. Mexican ammunition was running low. The Texians sent messengers to Brazoria, seeking reinforcements. With all this in mind, the fort commander offered to surrender.

After some back and forth, the Mexican troops were put on a ship to Matamoros. They carried minimal supplies. Fort Velasco’s cannon and swivel gun were left behind—as were the Mexican wounded, who were cared for by Texian doctors.

Travis and the other prisoners, who were being held in nearby Anahuac, were soon released and the Texian militia dispersed. The casualty count from the Battle of Velasco was pretty even on both sides: The Texians suffered seven killed and 14 wounded, while five Mexicans died and 16 were wounded.

Velasco was the first time Mexicans and Texians shed each other’s blood. But from there, things happened quickly. Santa Anna became Mexico’s president the following April. He began cracking down on the Texians, who bristled and declared independence in March 1836. And then those names—The Alamo, Goliad, San Jacinto—achieved a new luster, ones that overshone the seminal Battle of Velasco.