A tour of the conflict’s historic sites is a poignant reminder of how unmerciful war was meted out

against the state’s Native people.

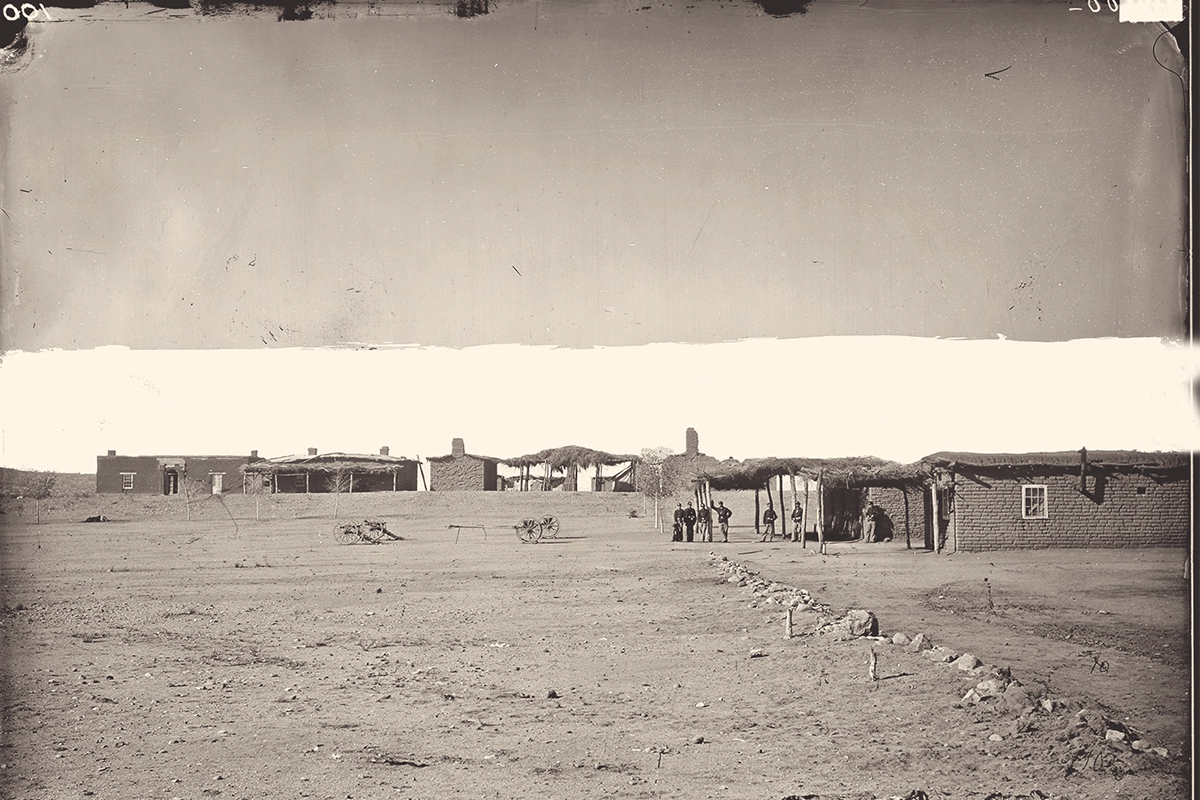

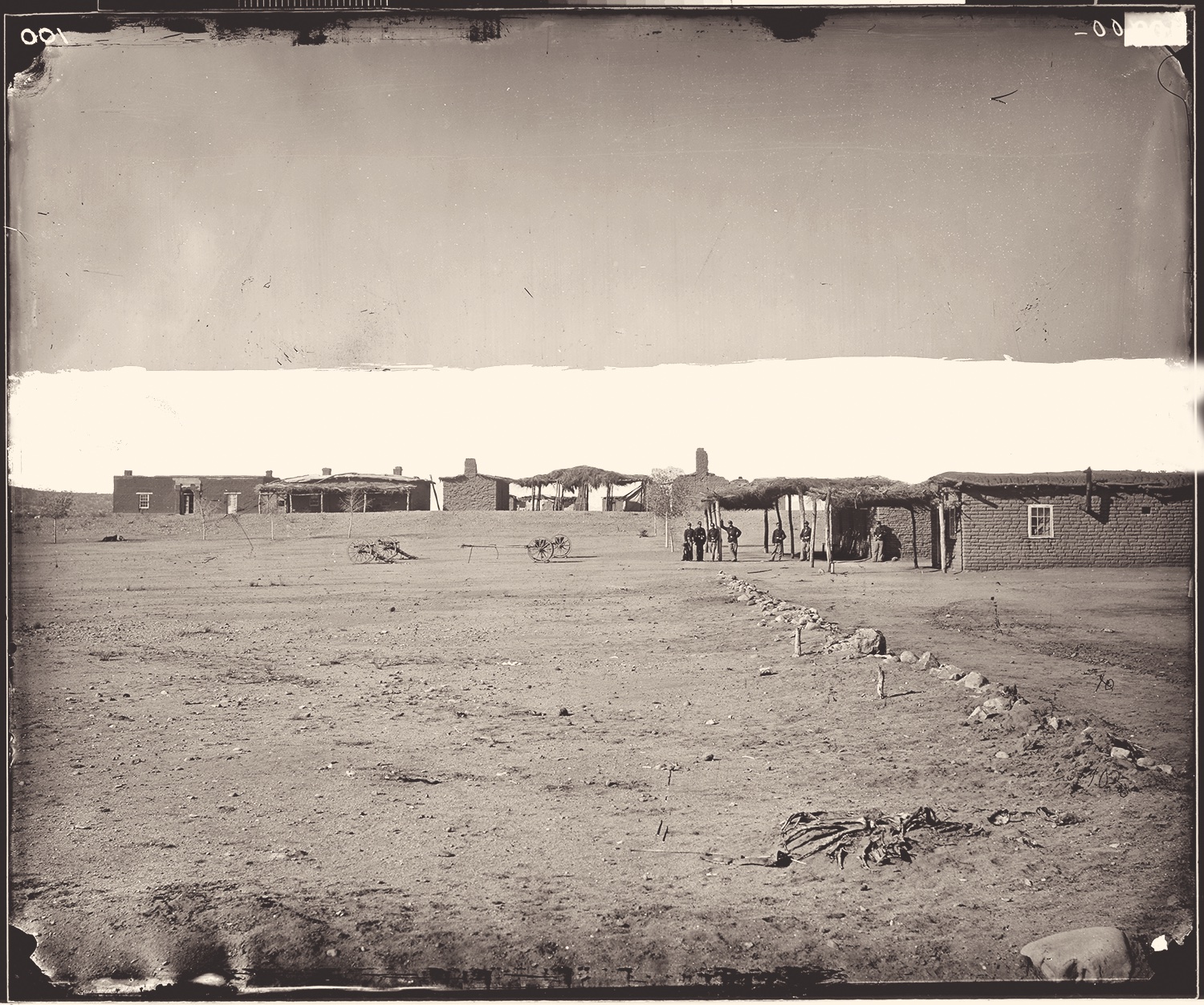

Timothy O’Sullivan, NARA, no. 524203

General George Stoneman, commander of the Department of Arizona, was not a popular figure in Tucson in 1871. While the Army and civilians waited for the establishment of reservations, Apache Indians were issued rations at what the locals called “feeding stations.” The soldiers, many civilians thought, should have been fighting Apaches rather than feeding them or building roads.

In early 1871, a few small bands of Pinal and Aravaipa Apaches began settling at Camp Grant, even though 3rd Cavalry Lt. Royal E. Whitman, a New Englander, told the Apaches he had no authority to establish a reservation. Still, more Indians came to Camp Grant, while Chiricahua bands continued waging war against white and Hispanic settlers in what had been their country. “As we declared at the time, the Camp Grant truce was a cruel farce,” Tucson’s Arizona Citizen declared on April 15. On April 28, a large party of Anglo and Mexican Americans and American Indians left Tucson and reached Camp Grant before Sunday, April 30, dawned. Then they attacked the Apache camp while most of the Aravaipa and Pinal men were away hunting.

“Men, women and dogs were clubbed,” William H. Bailey wrote in a manuscript located at the Arizona Pioneers’ Historical Society. “I never saw so many dogs in such a small place.… Some Apaches that escaped the clubs of the Papagos tried to climb the side of the gulch. They were shot down by the Mexicans and Americans on the side of the gulch.”

In less than a half hour, 144 Apaches, most of them women and children, were dead. Another 29 children were taken into Mexico by Tohono O’odham warriors and sold into slavery.

Survivors fled north, finding allies in the Tonto Basin. The Yavapai War had begun.

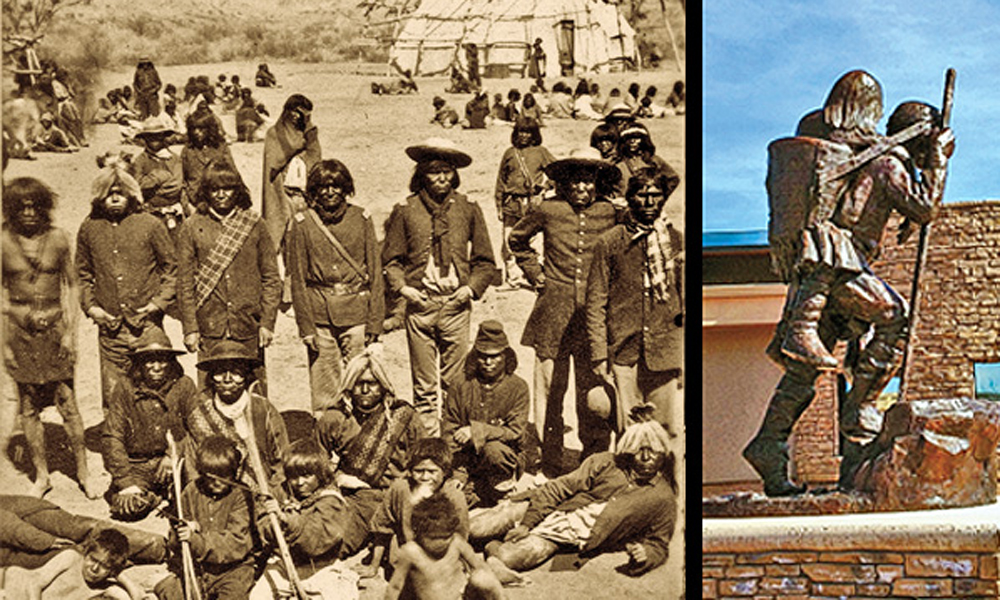

Photo by Johnny D. Boggs

In On the Border with Crook, John G. Bourke called the massacre “one of the saddest and most terrible in our annals…one over which I would gladly draw a veil.”

And that veil remains drawn. Little to nothing remains of Old Camp Grant, north of Tucson off State Highway 77 on what is now the Aravaipa Campus of Central Arizona College in Winkelman. (Old Camp Grant isn’t to be confused with Fort Grant, established in 1872 as a camp, promoted to fort in 1879, and located southwest of Safford.) You won’t find much in the way of historical markers or monuments on the Central Arizona College campus. One might think that Arizona wants to forget what happened here in 1871. In fact, while Cochise, Geronimo and much of the Apache Wars capture plenty of attention from historians and tourists, the Yavapai campaign is often overlooked.

Photo by Johnny D. Boggs

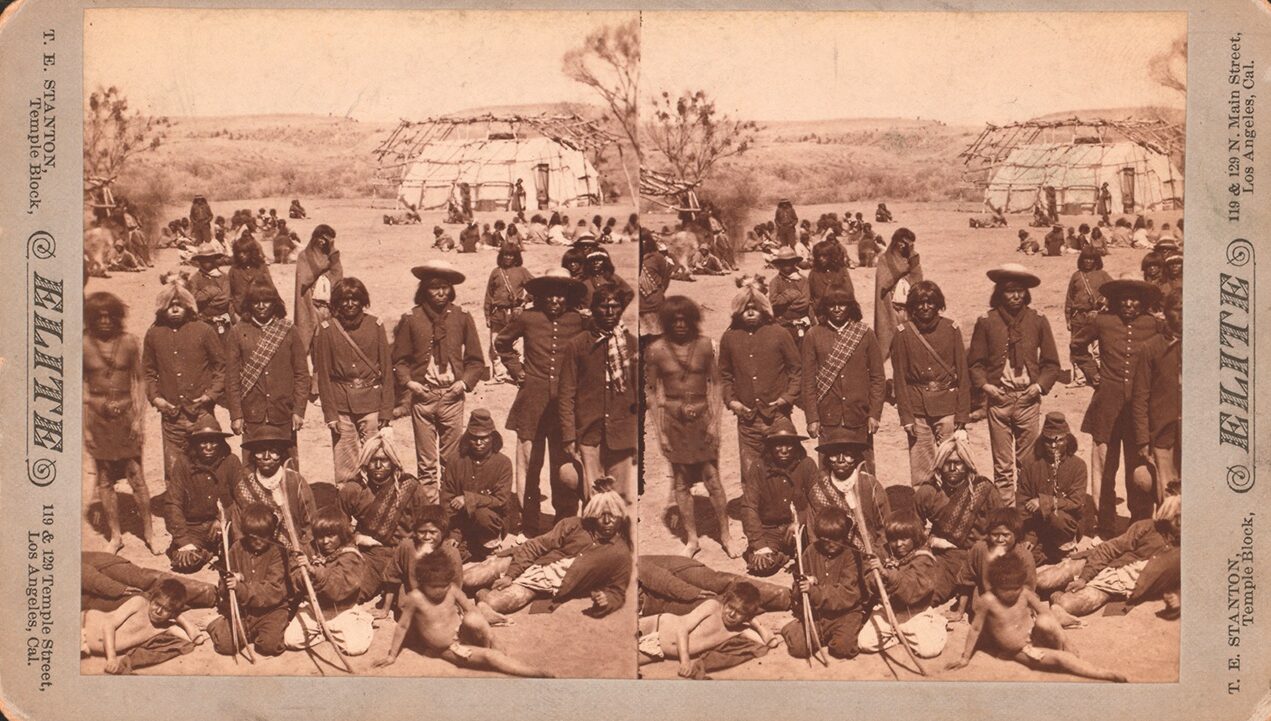

Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections

CROOK ARRIVES

On June 4, Lt. Col. George Crook officially replaced Stoneman as head of the Department of Arizona, and later that year 100 Tucson residents were tried for murder in Tucson (Arizona State Museum; Mission San Xavier del Bac; El Presidio Historic District). Five days of testimony led to 19 minutes of deliberation before the jury ruled the defendants not guilty.

But the war wasn’t limited to southeastern Arizona. On November 5, a stagecoach carrying seven passengers pulled out of Wickenburg (Desert Caballeros Western Museum; Jail Tree; nearby Vulture City) for California. An attack, presumably by Indians, though a female passenger reportedly pinned the crime on Mexicans dressed as Apaches, left five passengers and the stagecoach driver dead. One of the slain was a correspondent for Appleton’s Journal. An Army officer ruled that Indians from Date Creek were responsible.

Camp Date Creek had been established in 1870 as another temporary reservation for the Yavapai Apaches, who agreed not to molest travelers on the road between Wickenburg and Prescott (Sharlot Hall, Phippen and Fort Whipple museums and Museum of Indigenous People).

With the treaty considered broken, Crook went after the Apaches in force.

From Wickenburg, follow U.S. 60 to metropolitan Phoenix (Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West; Pioneer Living History Museum; Heard Museum), Superior (Superior Historical Society/Bob Jones Museum) and Globe (Besh-Ba-Gowah, Gila County Historical museums; Old Dominion Historic Mine Park) before reaching Salt River Canyon on the border of the White Mountain Apache reservation.

True West Archives

Courtesy Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress

SALT RIVER CANYON

On December 28, 1872, Apache scouts led roughly 120 soldiers of the 5th Cavalry to a cave near Salt River Canyon, where more than 100 Yavapai Apaches were holed up. Recalled Bourke: “The men on the first line had orders to fire as rapidly as they chose, directing aim against the roof of the cave, with the view to having the bullets glance down among the Apache men, who had massed immediately back of the rock rampart.”

Rocks were also hurled down into the cave. When soldiers descended the treacherous slope and entered what Bourke called “scarcely a cave at all, but rather a cliff dwelling, and of no extended depth” they found “men and women dead or writhing in the agonies of death, and with them several babies, killed by our glancing bullets, or by the storm of rocks and stones that had descended from above.” More than 70 Yavapai Apaches were dead.

On March 11, 1873, Apaches killed three white men, torturing one, which sent Capt. George M. Randall of the 23rd Infantry to a Yavapai camp in the Bloody Basin north of Perry Mesa, about 60 miles north of Phoenix and due east of Agua Fria National Monument. On the morning of March 28, soldiers surprised the Apaches on Turret Peak. The number of Apache dead reportedly numbered between 25 and 60, some of whom leaped or fell to their deaths from the rugged peak.

True West Archives

On April 6, the Apaches surrendered to Crook at Camp Verde (Fort Verde State Historic Park). For two years, approximately 1,500 Apaches and Yavapai lived on the 800-square-mile Rio Verde Reservation in the Verde Valley.

On February 27, 1875—Exodus Day—more than 1,400 Yavapai and Tonto Apaches were moved to San Carlos east of Globe, escorted by Lt. George O. Eaton, 15 troopers, chief of scouts Al Sieber and Tonto Apache scouts. Following the Mogollon Rim, they moved through present-day Payson (Rim Country Museum and Zane Grey Cabin), where some soldiers let sore-footed children and the elderly ride Army horses.

While the Indians struggled across the Salt River, L. Edwin Dudley, the U.S. special commissioner of Indian Affairs who was in charge of the relocation, thought about “another exodus, and I wished that the waves might again be rolled back.”

The Indian prisoners reached the reservation on March 20, minus more than 100 Apaches who had started, some who escaped into the mountains, others who died on the Apache “Trail of Tears.”

“A sadder pilgrimage,” historian Dan L. Thrapp wrote, “was never seen under Arizona skies.”

A WIDE SPOT IN THE ROAD

Yavapai-Apache Nation

True West Archives

After being held as prisoners of war on the San Carlos Reservation for 25 years, the Yavapai Apaches began returning to their homeland near Camp Verde at the turn of the 20th century. Today, the Yavapai-Apache Nation welcomes visitors. Montezuma’s Castle and Tuzigoot national monuments are nearby, and Cliff Castle Casino Hotel (CliffCastleCasinoHotel.com) opened in 1995 and features Storytellers, a high-end restaurant, and the Verde Bar. The Yavapai-Apache Nation Cultural Resource Center (Yan-Culture.org) includes a gift shop that sells American Indian arts and crafts as well as a research center and archives with a collection of books, diaries, images, oral histories, reference materials and videos. An 1875-1900 Return Commemoration is held each February. Yavapai-Apache.org

GOOD EATS AND SLEEPS

Good Grub: Matt’s Big Breakfast, Phoenix, AZ; Udderly Divine, Camp Verde, AZ; The Palace Restaurant and Saloon, Prescott, AZ; Beeline Café, Payson, AZ; San Carlos Café, San Carlos, AZ

Good Lodging: Hotel Congress, Tucson, AZ; White Stallion Ranch, Tucson, AZ; Flying E Ranch, Wickenburg, AZ; Hassayampa Inn, Prescott, AZ; Chrysocolla Inn, Globe, AZ