Trace Adkins follows in the footsteps of Gene Autry, Roy Rogers and Johnny Cash.

It’s been a great year for Trace Adkins, the six-foot six-inch former oil-field roughneck with the voice too deep to classify. The CMA Award-winner has released his 13th studio album, The Way I Wanna Go, to mark the 25th anniversary of his first. He’ll again host INSP’s Ultimate Cowboy Showdown. And another accomplishment: Trace Adkins is the first new Western movie star of the 21st century. He’s achieved that entirely with direct-to-streaming films.

All Images Courtesy Cinedigm Entertainment Group Unless Otherwise Noted

Gene Autry spearheaded the transition from country singer to Western actor in 1934, when he was hired to do the warbling in a Ken Maynard movie. Soon, Gene was starring in his own Westerns, often backed by The Sons of the Pioneers, featuring Roy Rogers, who would be starring in his own Westerns by 1938. The B-Western musicals’ ranks swelled to include Tex Ritter, Eddie Dean, et al. In A-Westerns and TV movies, Vaughn Monroe, Marty Robbins, Travis Tritt, Randy Travis, Reba McEntire and Naomi Judd all gave it a shot. In 1969, Glen Campbell triumphed, starring in, and singing the theme song for True Grit. In 1980, Kenny Rogers parlayed his hit, The Gambler, into a five-film television series.

Then there were The Highwaymen. In 1959, Johnny Cash sang the theme for The Rebel, and guested on Wagon Train, followed by Kris Kristofferson, acting in 1971’s The Last Movie, before starring in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. In 1979 Willie Nelson saddled up for The Electric Horseman, then a string of his own films. In 1986 Waylon Jennings got on board when the four joined forces for the remake of Stagecoach.

“I kinda got bit by the acting bug doing plays in high school,” Adkins recalls, “but I didn’t pursue it. Once I started doing videos, it bit me again.” He did cameos, guest appearances and played The Angel of Death in An American Carol. In 2012, he played a dangerous client in The Lincoln Lawyer. “Matthew McConaughey knew I was nervous. He rehearsed scenes with me, went out of his way to make sure I was comfortable. That’s probably the best movie that I’ve ever been lucky enough to be in.” In terms of Adkins’s role, it could have been a Western. “You know, I either ride a horse or a motorcycle in most movies I do.”

A year later, he made his first Western. “That just fell in my lap. I was out in L.A., supposed to fly home the next day, and my agent called and said, ‘Hey, there’s an opportunity for you to do this Western, and you only have to be there two days.’” Wyatt Earp’s Revenge is the fact-based story of the killing of Dora Hand by Spike Kenedy. Adkins plays Spike’s protective father, rancher Mifflin Kenedy, cofounder of the King Ranch. Surrounded by earnest 20-somethings as Earp and company, Adkins dominated his every scene.

In his next Western, Adkins played the original man with no name in a very different take on The Virginian. “That was nerve-wracking; that was the first time I was the lead in a movie, and I’ve only done it once more since. Ron Perlman [as Judge Henry] was just incredible fun to work with. I was pretty awestruck by him.” And in an elegant example of life imitating art, Adkins married the schoolmarm, or the actress who played her, Victoria Pratt. Next, Adkins portrayed a reformed outlaw who un-reforms when his wife dies, in Stagecoach—The Texas Jack Story.

In Traded, where would-be Harvey Girls are forced into white slavery, Michael Pare was the good guy, and Adkins the villain. “I like playing the bad guy. I may be better suited to it.” He also got to act with one of his idols. “I can’t put into words what an honor that was, to work with Kris Kristofferson. I’ve done a few shows with him over the years, but I always wanted to do a movie with him.” They’ve done a second together, Hickok, starring Luke Hemsworth and Bruce Dern, who introduced himself with, “‘Hey, I’m Bruce Dern. I was the first man who ever killed John Wayne in a movie! How you doin’?’ He was great.”

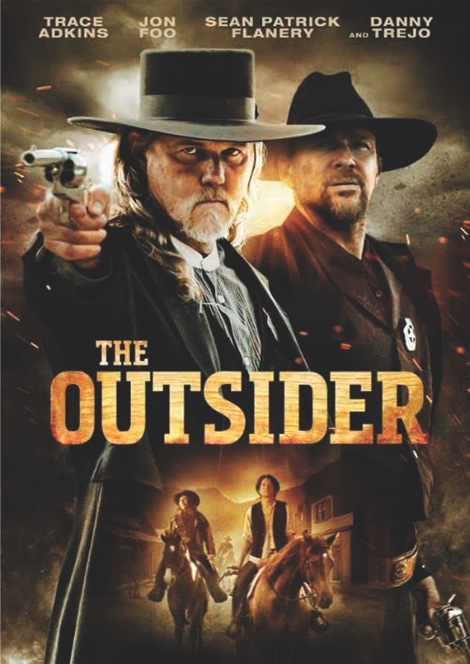

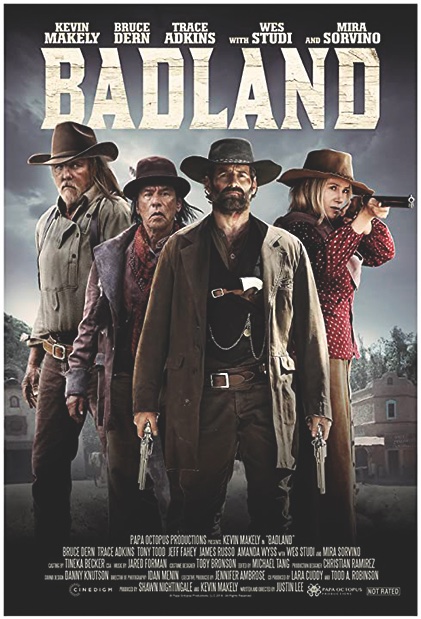

Since then, Adkins has been in Bad Land, and played a lawman father hunting down his homicidal son in The Outsider. “That was the only one that really bothered me as I was doing it, not to mention how I felt when I watched it. I probably would have killed that boy a lot earlier,” he says with a laugh. “He was a bad seed.”

That hasn’t put him off Westerns. “It was the most interesting, romantic time in our history, post-Civil War, the cowboy era. The myth has outgrown the reality, but that’s partly why we enjoy Westerns so much.” And a good thing: he has three more, Old Henry, Apache Junction and The Desperate Riders, set to be released soon.

DOCUMENTARY REVIEW

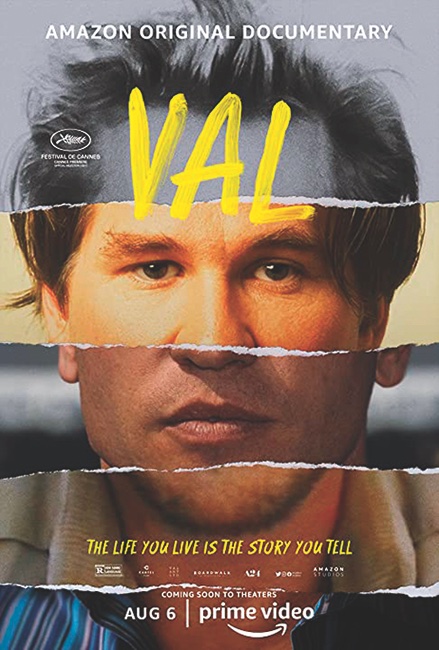

VAL

While one must wonder at the self-fascination that compelled Val Kilmer to record thousands of hours of his life, directors Leo Scott and Ling Poo have distilled that raw material into the memoir of an actor whose once-enigmatic choices come to not only make sense, but seem inevitable once you know him—and you will know him when you’ve seen VAL.

The youngest student admitted to Julliard, he was driven. He pumped joy into the broad comedy of Top Secret. He suffered through as a stoic (you’ll learn why) Batman, and worked to make Top Gun’s Iceman a flesh-and-blood villain—incidentally, he’s back with Tom Cruise in Top Gun: Maverick. Decades before it became the norm, he filmed auditions unrequested, not getting a part in Full Metal Jacket, but snagging the role of Jim Morrison in The Doors, and admittedly making the life of wife Joanne Whalley a Hell in the process.

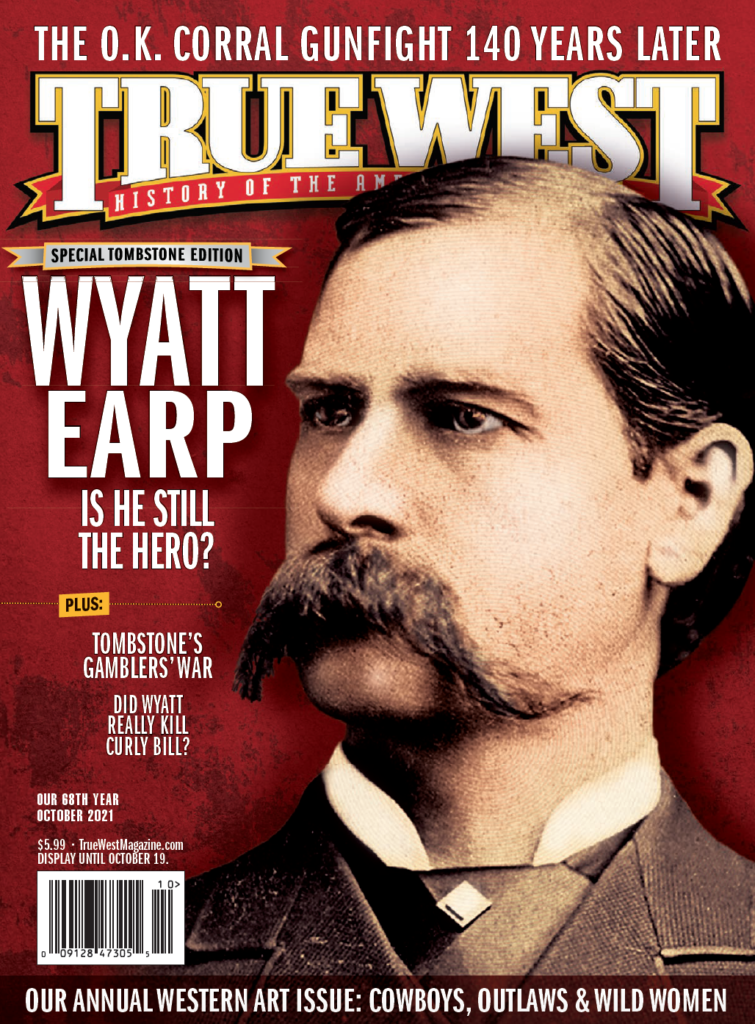

Raised on Roy Rogers’ ranch—good story there—by a Texan father who instilled in him a love of the West, how perfect that he should achieve film immortality as Doc Holliday in 1993’s Tombstone.

As he once said, “I’d be in a bad Western on a good horse any day of the week.” A poet, playwright and screenwriter, in his later career he’s been drawn to Mark Twain, in whose personal life he sees many parallels; he’s filmed a one-man show.

Courtesy Cinergi Pictures Entertainment/Buena Vista Pictures

A devout Christian Scientist, he long delayed treatment for throat cancer, and now can barely speak; his son, Jack, narrates for him. Though frail, he still acts, and attends Western events, where he’s warmly embraced. He signs pictures for a fee, a business he acknowledges some consider as low as an actor can sink. “But it enables me to meet my fans. I feel grateful.”

Henry C. Parke, Western Films Editor for True West, is a screenwriter and blogs at HenrysWesternRoundup.blogspot.com. His book of interviews, Indians and Cowboys, will be published later this year.