– All photos Courtesy Utah Historical Society unless otherwise noted –

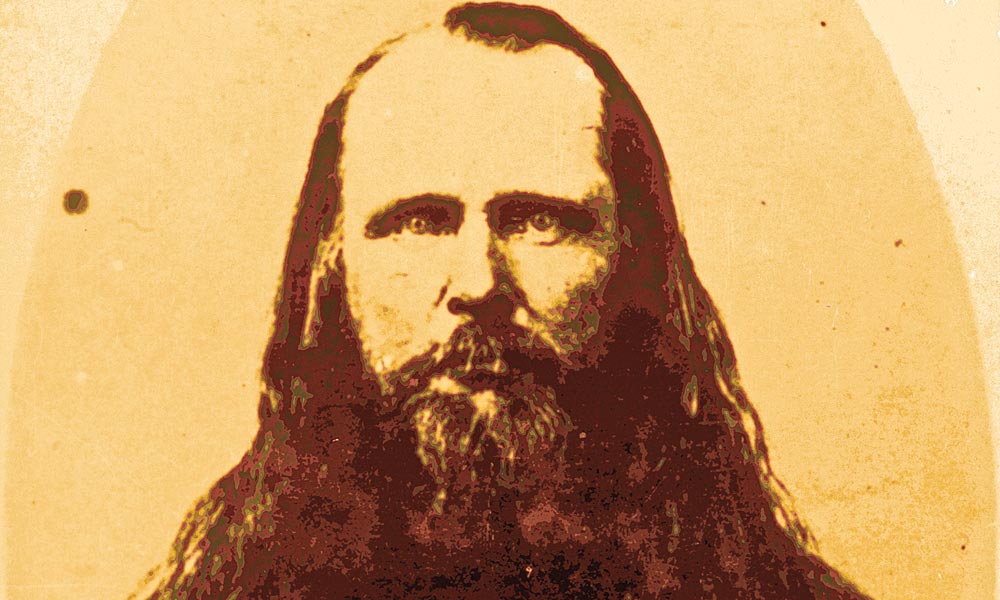

One thing is certain: Porter Rockwell shot and killed Lot Huntington at Faust’s Station on January 16, 1862. All accounts agree on that—but not much more.

The debacle started about two weeks earlier, when Lot and a few others beat the hell out of John W. Dawson as he attempted to flee Utah Territory, where he had served as governor for all of three weeks. The politician had done nothing to endear himself to the people of Utah during his brief tenure, but did much to earn their ire—including propositioning a respectable Mormon woman.

Dawson left Salt Lake City and sought refuge at a stage station at Mountain Dell to await an outbound coach. But he found no sanctuary. A rowdy named Wood Reynolds, said to be a relative of the insulted woman, with his sometimes partners-in-crime Moroni Clawson and Lot, along with others, set upon the governor in a drunken fracas. They left him beaten, without even the comfort of a beaver fur stole, which they pilfered, along with the governor’s blankets, before riding away.

The men “began and continued a most serious violence to me, wounding my head badly in many places, kicking me in the loins and right breast until I was exhausted..,” Dawson stated in a letter to The Deseret News, published January 22.

He named his assailants, writing of them that “it should be the unremitting duty of the people of Salt Lake City to bring to speedy trial and condign punishment.”

While no one in Utah Territory was much interested in punishing the men who gave Dawson a deserved punishment in their eyes, authorities did issue arrest warrants, but made little effort to serve them.

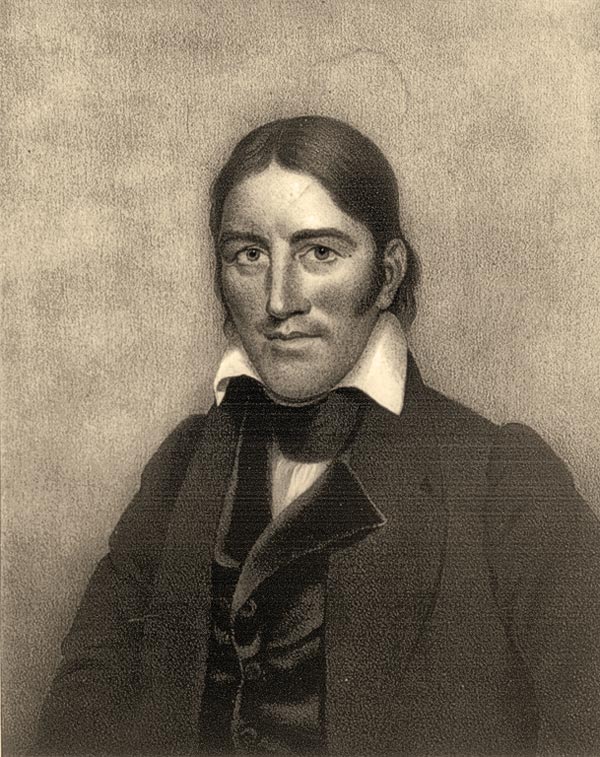

—David Crockett

Then Lot doubled down on his allure to the law when he was accused, with friend John Smith, of lifting $800 from an Overland Mail strongbox at Townsend’s Stable. Now he had to flee the territory.

Clawson and John Smith joined him in the escape. They might have succeeded if Lot had not stopped in the town of West Jordan and stolen a horse called Brown Sal. Tied to a fencepost by John Bennion, who was attending a late-night meeting, the mare was a prized possession of the family and particularly loved by John’s son Sam. When John arrived home in the wee hours, following a four-mile walk through the January night, Sam, angered by the theft of the horse, gathered a posse and launched a pursuit. Leading them was John’s friend Porter Rockwell, 48, who was widely regarded throughout the West for his abilities as a tracker and manhunter.

“He Had His Little Faults”

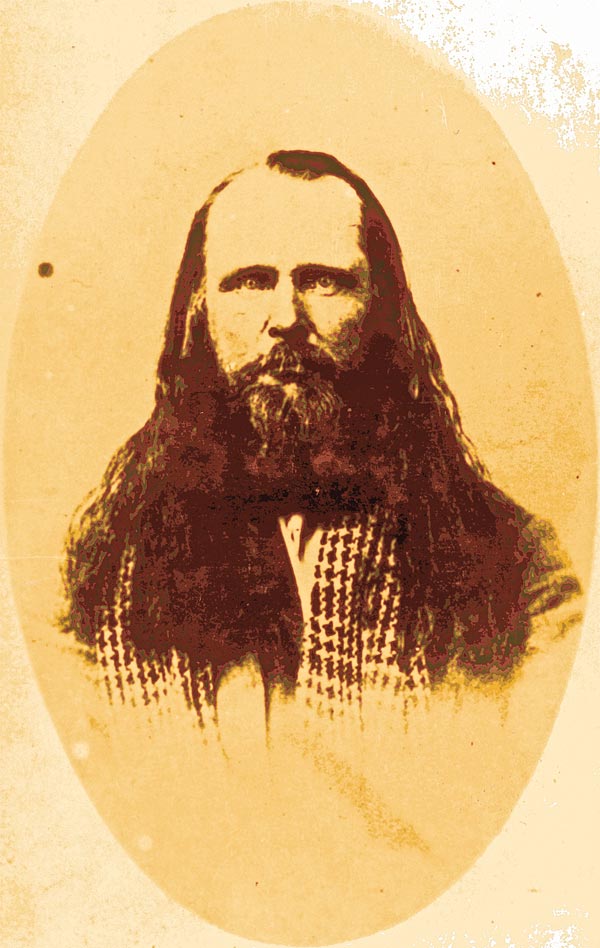

A deputy U.S. marshal, Rockwell was considered by many to be an outlaw, as they suspected him of committing numerous murders in service to the leaders of the Mormon church. He was a boyhood friend of church founder Joseph Smith and served as his bodyguard, a role he also filled for Joseph’s successor, Brigham Young.

Near the end of the Mormons’ sojourn in Illinois in 1845, Rockwell shot and killed Frank Worrell, who led the militia unit responsible for Smith’s murder. Rockwell was suspected of—and had been jailed for—the 1842 attempted murder of Lilburn Boggs who, as governor of Missouri, drove the Mormons from the state. While Rockwell was escorting a group of would-be gamblers, led by John Aiken, out of Utah Territory in 1857, they ended up dead. About 20 years later, Rockwell was awaiting trial for that crime when he died. Dozens of other killings were assigned to his account.

Whether outlaw or lawman or both, Rockwell was feared and respected throughout the frontier. Scout, hunter, tracker, rancher, gunfighter, driver—his many skills placed him among the most storied pioneers of his day. He was famous, and infamous, from the Mississippi River to the California gold fields.

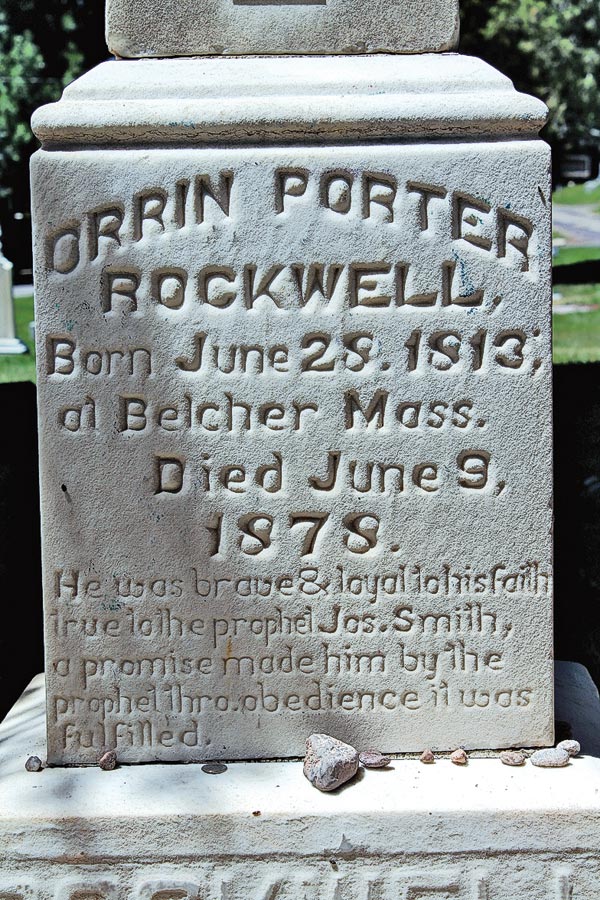

“He had his little faults, but Porter’s life on earth, taken altogether, was one worthy of example, and reflected honor upon the Church. Through all his trials he had never once forgotten his obligations to his brethren and his God,” Mormon Apostle Joseph F. Smith said in his eulogy at Rockwell’s 1878 funeral.

The Salt Lake Tribune offered a different opinion when reporting his death: “Porter Rockwell is another of the long list of Mormon criminals whose deeds of treachery and blood have reddened the soil of Utah, and who has paid no forfeit to offended law…. He killed unsuspecting travelers, whose booty was coveted by his prophet-master. He killed fellow Saints who held secrets that menaced the safety of their fellow criminals in the priesthood. He killed apostates who dared to wag their tongues about the wrongs they had endured. And he killed mere sojourners in Zion merely to keep his hand in.”

A Man of Contradictions

But in January 1862, Rockwell was very much alive and was trailing Lot. A long-time associate of Lot’s father, Dimick, Rockwell had known the boy all his life. Never mind. He was after the outlaw and meant to have him.

Fiercely loyal to whoever he was working for at the time, Rockwell walked a fine line between outlaw and lawman. As a deputy U.S. marshal, he spent much of his time rounding up lawbreakers in Utah Territory. He was often willing to set aside personal allegiances in pursuit of enforcing the law or accomplishing whatever mission his Mormon leaders assigned him. He would have subscribed to David Crockett’s statement, “First be sure you’re right, then go ahead.”

– By Rod Miller –

The trail led south out of Salt Lake Valley, then veered west toward Camp Floyd—recently re-christened Fort Crittenden when its namesake, Secretary of War John B. Floyd, absconded to the Confederacy. Rockwell and his posse pushed hard, trying to make up the criminals’ head start of some 24 hours.

Accounts differ concerning Lot’s flight. Some claim all three men were mounted. Others say they had only two horses, with the men taking turns on shanks’ mare. They pushed westward on the Overland Trail, past Fort Crittenden. When Rockwell’s party arrived there, cold and tired, the leader surmised his prey had pushed on to a stage stop some 20 miles on, to overnight there.

Rockwell borrowed a stagecoach and team to complete the journey in relative comfort. Given his history of recovering property and arresting bandits for the Overland Mail, the company was happy to cooperate. They pushed on to Faust’s Station, operated by German native Henry Jacob “Doc” Faust. The Rush Valley layover had served George Chorpenning’s “Jackass Mail,” the Pony Express as a home station and now the Overland Stage as a stagecoach stop. Rockwell arrived before dawn and secreted his men at strategic points around the station and himself behind a stack of cedar fence posts.

After frigid hours of waiting, Rockwell saw Faust come out for morning chores. He waved the agent over and asked about the outlaws. Faust said they were inside, eating breakfast. Rockwell sent him back with an order to surrender.

A Higher Allegiance

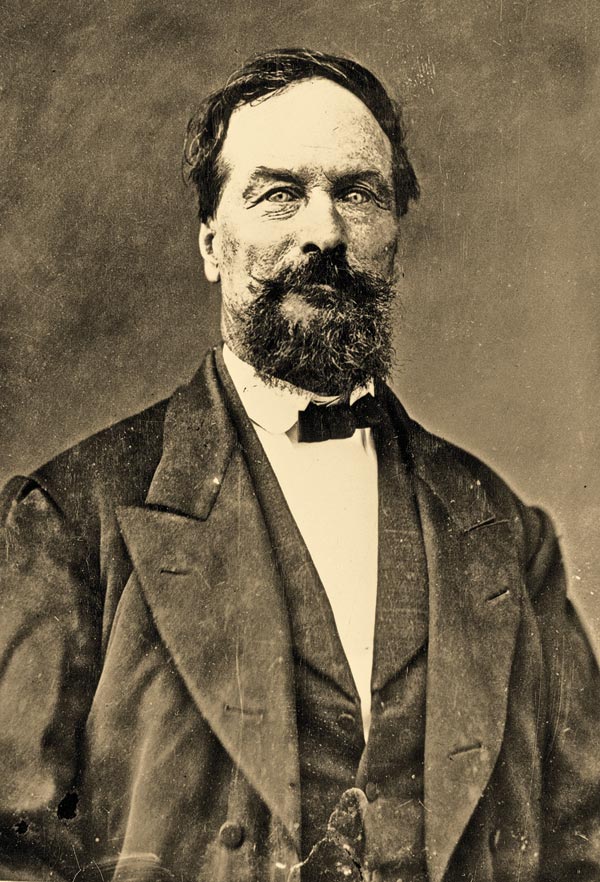

Lot came out alone, pistol in hand, heading for the corral and Brown Sal. The 27 year old was tall and strongly built, and a crack shot. Just more than two years earlier, he had been wounded in a gunfight with “Wild Bill” Hickman, another enforcer for the Mormon church.

Lot fired, and one of his bullets shattered Hickman’s hip, leaving fragments of lead that would trouble Hickman for the rest of his days.

As Lot fled, a ball from Hickman’s pistol punched a hole in the younger man’s backside and lodged in his groin, beyond retrieval.

On this January morning, the now wounded Lot became no match for his father’s close friend. Rockwell apparently yelled at Lot to surrender. The outlaw instead mounted Brown Sal bareback and aimed his revolver at Rockwell. The Mormon Enforcer fired, filling Lot with a load of double-aught buckshot.

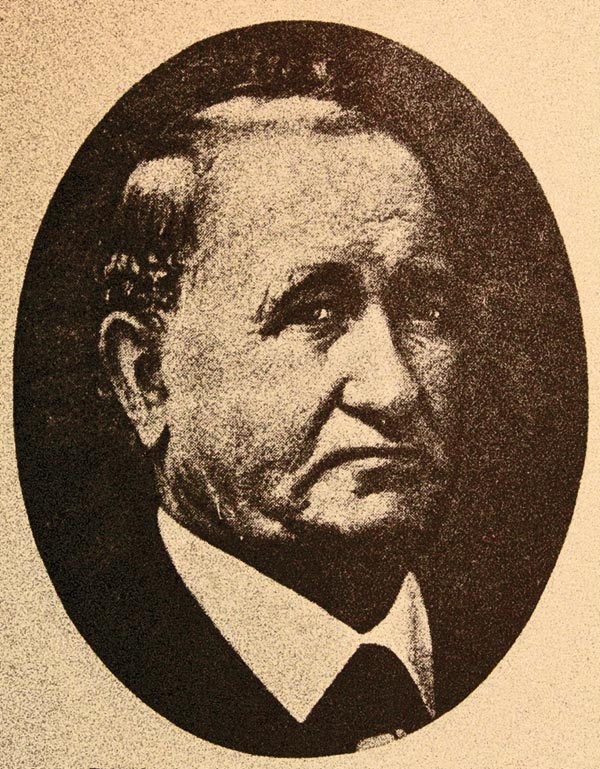

– Bennion photo Courtesy Joseph Bennion; Huntington photo True West Archives –

Or, another account states, Lot concealed himself behind the horse, led it to a pole gate and started dropping the poles. The mare shied away, exposing Lot to Rockwell’s fire.

However the shoot-out happened, Lot ended up dead.

“[Lot] Huntington drew his revolver where upon he was shot in the belly with 8 slugs cutting the arteries to pieces. Huntington fell with part of his body in the corral and one leg outside of the corral. He bled to death in four minutes,” reported The Journal History of the Church, a daily history recorded by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Clawson and John Smith surrendered. “Porter and party have just returned with Clawson and Smith. [Lot] Huntington, in attempting to escape was killed. The party will leave here in about half an hour,” the Deseret News reported from a January 16 wire sent to the Overland Mail agent in Salt Lake City from the Fort Crittenden station.

Rockwell released the prisoners to the Salt Lake City lawmen and left. He had not gotten far when he heard gunfire.

“…the prisoners, supposing probably that the policemen were unarmed, started to run, and were shot at and both killed before getting far away,” the Deseret News reported.

Here, too, accounts differ. The aforementioned Hickman saw Clawson’s and John Smith’s bodies. “Both were powder-burnt and one shot in the face,” he claimed. “How could that be, and they running?”

How, indeed.

Spur Award-winning author Rod Miller writes history, fiction and poetry about the American West. His latest book is a novel, Rawhide Robinson Rides the Tabby Trail.