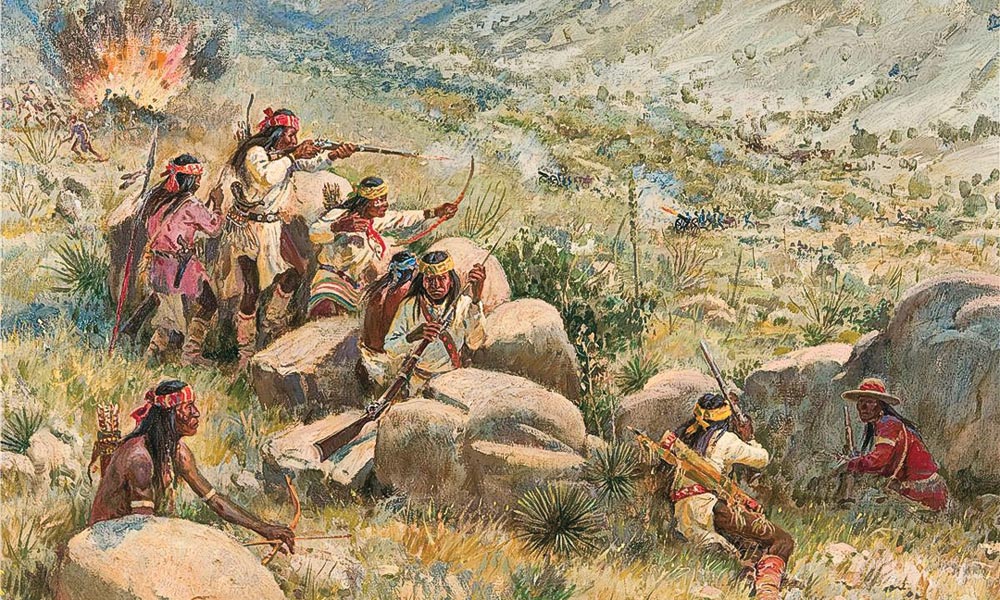

– Courtesy Scottsdale Art Auction, March 31, 2012 –

Perhaps war between the U.S. and the Apaches was inevitable. They were once united by a hatred of Mexico, but the alliance began to change in the 1850s, as more “white eyes” moved into Apache territory. Both sides took up arms, inflicting damage and death.

Things got serious in January 1861 when Coyotero Apaches raided the Ward ranch near Sonoita, Arizona Territory, and kidnapped Felix Ward (Mickey Free). Army officials blamed the wrong Indians.

At an Arizona Pass parlay in early February, Chiricahua leader Cochise denied knowledge of the kidnapping; Lt. George Bascom tried to take the Apaches into custody, but Cochise escaped and began attacks on Mexicans and whites.

Military officials then hanged Cochise’s brother and two nephews—and because of the so-called “Bascom Affair,” the war was on. The two sides would again meet at Apache Pass, the site of the first major battle.

For the U.S. Army, the conflict was something of a surprise.

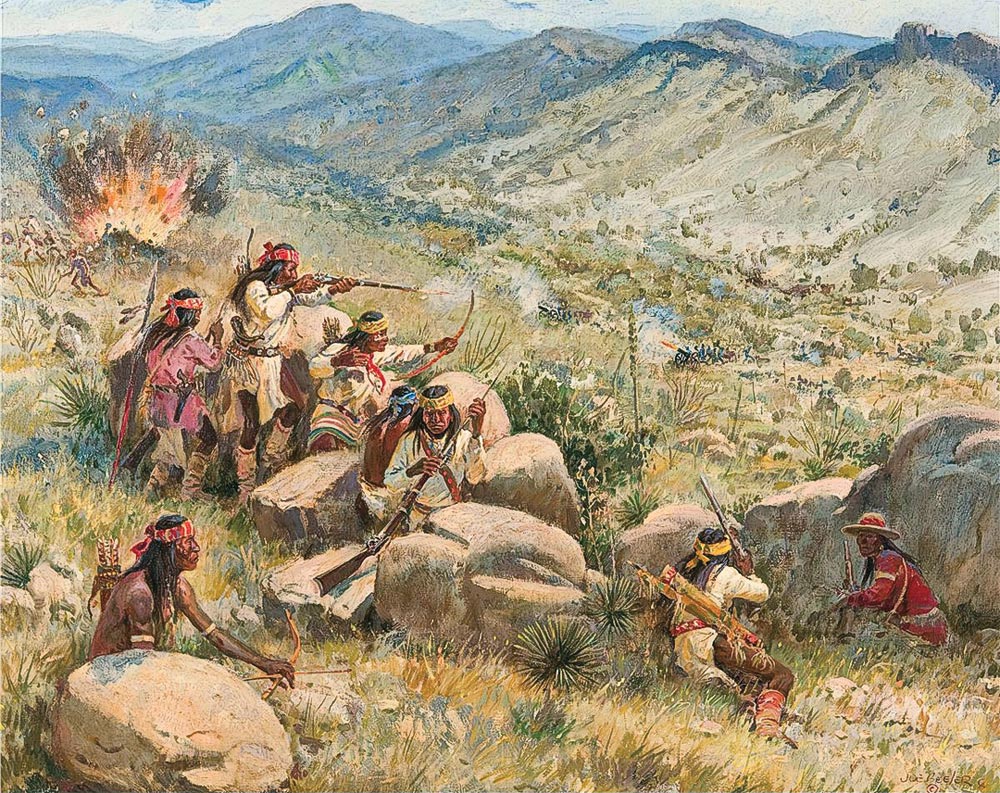

After capturing Tucson from Confederate forces on May 20, 1862, Col. James H. Carleton’s command moved east to take control of New Mexico Territory. An advance group reached the old Apache Pass stage station on July 15, exhausted by their march in extreme heat, torrential rains and on tough terrain. They didn’t realize that up to 500 Chiricahuas, from various clans, had been waiting. The Apaches fired bows and arrows, and rifle shots at the soldiers.

Army forces regrouped and got a couple of howitzers into play, the first time such weapons were used against Southwest Indians. Soldiers desperately sought life-giving water from the springs, some 600 yards away, but couldn’t reach it because the Apaches held the higher ground.

New Mexican Albert Fountain led a charge that drove out the Apaches. They retreated with their dead and wounded, and the soldiers finally reached the spring.

Seven soldiers galloped off on horseback to warn other units. Chiricahuas charged after them. While taking cover behind his dead horse, Pvt. John Teal fired a shot that hit the lead Apache—Mangas Coloradas. The warriors, led by Mangas’s son-in-law Cochise, immediately stopped and took their injured chief to safety (he survived, only to be murdered less than a year later).

The Battle of Apache Pass was over. Army casualties were two dead and two wounded. The Apaches may have suffered 10 dead and many more injured.

The Apache Wars would continue for nearly 25 years. The Apaches never again mounted the kind of force they had at Apache Springs, in size or involving various clans. From that point on, the conflict would be a bloody hit-and-run, guerrilla-style confrontation. Many would die on both sides before the U.S. defeated the Apaches and shipped most of them to Florida.