The Rough Riders were already the most famous outfit in the U.S. Army, but when the first contingents arrived at the “International” fairgrounds in San Antonio, Texas, in May 1898, the regiment’s headquarters and camp, they found they had no uniforms, no weapons, no tents, no blankets and no horses.

On May 9 and 10, most of the college men and “millionaire recruits,” as the swells were dubbed by the press, arrived. The Rough Riders at the fairgrounds had been tipped off that the Harvard men were in town and gathered quickly when they heard the trolley’s bell. Cheers and shouts erupted for these “college boys,” who quickly found themselves surrounded by 200 jostling troopers, each one wanting to shake their hands.

The millionaire recruits, mostly New Yorkers, dined at the Menger Hotel before beginning their lives as cavalrymen. They showed up at camp wearing new sombreros and blue flannel shirts, causing a San Antonio newspaper to comment that they could easily be mistaken for genuine Westerners “at a distance of several blocks.”

Unlike most of the Rough Riders, they carried valises with clean linens, razors, soap and choice cigarettes. The same newspaper, in another joke at the expense of the “Fifth Avenue boys,” suggested that “there were also a few hand mirrors in the valises.”

But the Rough Rider Westerners took much more kindly to the Easterners. Arthur F. Cosby, a 26-year-old New York lawyer and Harvard grad, wrote his father that the Western men he encountered “seem to like the New Yorkers, say they are ‘all right.’ I have heard one or two complain of them but not seriously—they all say the New Yorkers are ‘gentlemen’ and plucky.”

The Easterners earned the respect of the other men by willingly following orders and cheerfully undertaking chores, be it digging a ditch or hauling hay for the horses. Colonel Leonard Wood kept an eye on the college boys and clubmen and wrote to his wife, Louise, “You would smile to see the New York swells sleeping on the ground and on the floor of the pavilion we have without blankets and doing kitchen police for a troop of New Mexico cowboys, all working together and as chummy as can be.”

The fairgrounds had been selected as the Rough Riders’ camp because there was room for the hundreds of tents for the officers and men, and the adjacent Riverside Park had open space for the mounted drills. But Fort Sam Houston, located a few miles north of downtown, barely had enough tents on hand for the regiment’s officers. Until the Rough Riders’ “dog tents” arrived, the enlisted men had spread out in the large Exposition Building and the adjacent grandstand.

The lack of blankets, which, like everything else, were in transit, forced nearly all the Rough Riders to be “chummy.” The few blankets that could be scrounged up, some of which were saddle blankets and pads borrowed from the civilian mule packers, each had to be shared by two or three men.

Meeting Their Leader

Lieutenant Col. Theodore Roosevelt stepped off his train in San Antonio at 7:30 a.m. on Sunday, May 15. Record crowds of visitors came to the camp that Sunday afternoon and evening. Roosevelt was a celebrity unlike anyone San Antonio had seen in a long time. The San Antonio Express fawned over him:

Theodore Roosevelt is only about 35 years old but he has been a Western plainsman, a New York business man, a reformer, a politician, an author and several other things. But above all he is an American gentleman and a patriot. He will doubtless have a bright place in history as the man who resigned the comfortable, lucrative and distinguished position of Assistant Secretary of the Navy to go to the thick of battle…. He possesses an independent fortune, but he really has no use for it. He is essentially a man of action.

Approximately 10,000 people flooded through the fairgrounds that day, poking about here and there, asking countless questions of the men, most hoping to catch a glimpse of the famed lieutenant colonel.

Professor Carl Beck’s Military Band marched to the Rough Riders’ camp and formed a circle around Roosevelt’s tent. After the music stopped, the enlisted men shouted for a speech from Roosevelt.

He stepped out of his tent, smiled at the crowd, thanked the men for the warm welcome and told them what everyone who could read a newspaper already knew, that the “eyes of the entire civilized world were on them, and that they were expected to do what no others would do.”

“I expect you to acquit yourselves creditably,” he continued, “and I know I will not be disappointed. When we get to Cuba and get at the Spaniards, I want your watchword, my men, to be ‘Remember the Maine,’ and you shall avenge the Maine. We are expected to fight, and that we must do!”

His final words were met with wild cheers from the men, and Beck, sensing the moment, quickly got the attention of his musicians and started them playing “Yankee Doodle.” The men whooped and hollered even louder.

For many of the Rough Riders, this was their first exposure to Roosevelt, an intense and animated speaker who feared no audience. Later that evening, in talking over their impressions of the lieutenant colonel, one trooper said, “He looks as though he was there with the goods, only I don’t like the way he skins his teeth back when he talks to a fellow.”

– Courtesy Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University, R560.3.D83-010–

At Ease with Kings

and Cowboys

Roosevelt made no effort to hide his inexperience as a cavalry officer. He was often seen in camp holding the thick cavalry drill manual and loudly practicing various commands, completely oblivious to the troopers just steps away. His boyish enthusiasm for any task was contagious, and he talked down to no man—unless he deserved it. A journalist put it best: Roosevelt “was the greatest ‘mixer’ among the people that this country has ever produced, or probably ever will produce.” He was at ease with kings and cowboys, presidents and paupers.

His time as a rancher in the Badlands had made Roosevelt comfortable with many of the frontier types who formed the regiment. He had gone west years ago as a spectacle-wearing dude with expensive guns and a silver-mounted hunting knife made by Tiffany & Co., but he surprised everyone who mistook him for just another tenderfoot from the East.

Three fun-loving cowboys had made that mistake in 1883 in the small settlement of Medora, Dakota Territory. Roosevelt, then just 24, had stepped into a store to buy postage stamps when the cowboys switched the saddle and bridle from his mount onto a nearly identical mean bronc named White-Faced Kid and led away Roosevelt’s horse.

When Roosevelt pulled himself onto the saddle, White-Faced Kid hunched his back and flipped Roosevelt into the dirt. Roosevelt picked himself up and swung his leg up over the saddle. This time, the Kid didn’t wait for Roosevelt to get seated. The bronc shot its rear legs out and bucked its rider over its head. Roosevelt did a somersault and landed with a thud, breaking his spectacles.

The laughing cowboys ran up and helped a stunned Roosevelt to his feet. Roosevelt paid them no mind, however, saying only, “It’s too bad I broke my glasses,” as he limped into the store.

Just as the cowboys were about to switch the horses, Roosevelt came out, wearing a pair of glasses he had fetched from his bag, and walked to White-Faced Kid. He jumped into the saddle and clamped his knees onto the bronc’s sides. The Kid leaped forward and broke into a gallop, speedily disappearing down the road.

The cowboys weren’t laughing now; they were worried the tenderfoot might break his neck. A minute later, though, the Kid galloped back with a grinning Roosevelt firmly in the saddle. Roosevelt let out a whoop as he pulled on the reins and halted in front of the cowboys. “We took a shine to him from that very day,” one of the tricksters recalled.

Roosevelt just as quickly won over the men of the Rough Riders. Trooper Kenneth Robinson, a Scotsman and cousin by marriage to Roosevelt’s sister Corinne, observed: “The men always do their best [drilling] when he is out. He would be amused indeed if he heard some of the adjectives and terms applied to him, meant to be most complimentary but hardly fit for publication.”

Trooper Alvin C. Ash stayed far away from those salty adjectives in writing to his mother about Roosevelt. He simply said that the lieutenant colonel was the “most magnetic man I ever saw.”

Dressing for War

On May 14, the brown canvas uniforms were issued, each man receiving coat and trousers, canvas leggings, one pair of socks, one pair of shoes and the Western-looking Model 1889 campaign hat (underdrawers and wool shirts were still in transit).

An item of apparel that was not Army issue, but became a Rough Rider signature, was the bandanna. Probably some cowpunchers decided they couldn’t part with their silk bandannas and simply wore them with their uniforms. It was the perfect touch for a body of cowboy cavalry, and soon troopers were taking the trolley downtown to buy bandannas. Roosevelt sported a blue bandanna with white polka dots, as did many of his men.

The coveted Krag-Jorgensen carbines and Colt revolvers were distributed to the men on May 19 and 20, and the troopers admiringly ran their hands over the carbines’ wood stocks, worked the bolt actions and sighted down the barrels. But the arrival of two menacing-looking machine guns caused the biggest stir in camp. Manufactured by Colt of Hartford, Connecticut, the same company that made the regiment’s revolvers, these gas-fired, belt-fed automatic weapons were gifts courtesy of the millionaire recruits. Each gun could fire 500 rounds in a minute flat, and at 3,000 yards, the bullets would “tear human beings to pieces.”

The Colts came with 10,000 rounds of ammunition, which Col. Wood pointed out weren’t nearly enough for the coming campaign. A further complication was that the guns did not fire the same cartridge as the Krag-Jorgensens, instead taking a 7 x 57 mm—the same round used in a Spanish Mauser. Wood thought for a second and said, “All right, we’ll capture the ammunition for them from the Spaniards.”

Everyone, Roosevelt especially, was anxious to see the guns fired, so both guns, 115 pounds each with their heavy tripods, were carried a short distance to the San Antonio River. A steady pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop spewed from the guns as plumes of water sprayed up from the river and chunks of mud from the opposite bank flew into the air. The guns didn’t jam once.

The Winchester Repeating Arms Company of New Haven, not to be outdone by its Hartford rival, also shipped a weapon to San Antonio. It was a Model 1895 Winchester lever-action carbine specially made for Roosevelt. It sported a nickel steel barrel and English walnut stock with a saddle ring mounted on the left of the receiver. Most important, it was chambered for the .30-40 round, the same used for the Krags.

Roosevelt had made no secret of his admiration for Winchester’s lever-action repeaters. He especially liked the Model 1895, which, in the right hands, was capable of getting off two to three shots per second. “I may not shoot well,” Roosevelt had said once, “but I know how to shoot often.” Surprised and pleased by the gift, he promised to use the Winchester to avenge the Maine.

Horses for Heroes

Each day, horses for the troopers had been driven into camp in bunches of 25 and 30 from Fort Sam Houston, where they were being inspected and purchased. Officers either bought their horses locally or had their own horses shipped to them by rail (the latter were generally the finest horseflesh in camp).

The public notice from the Quartermaster’s Department called for horses that were “well broken to saddle,” but Oklahoma broncobuster Bill McGinty noted that the horses purchased “hadn’t been broke but once if that.” The first time the troopers were given the order “Mount,” at least 300 horses began to buck, throwing riders left and right. “By the time the dust cleared,” recalled McGinty, “them eastern boys were scattered all over Texas.”

In the early going, the antics of the rough range stock was costing the regiment about a man a day, “knocked clean out.” Several Easterners wisely hired the more experienced bronc riders in the regiment to “take some of the devilishness” out of their mounts.

In addition to getting cavalrymen and cavalry horses to cooperate with each other, the horses had to be trained to ignore gunfire—or at least put up with it. Otherwise, a bucking exhibition would erupt the first time a shell exploded on the battlefield. To accomplish this, the troopers stood in formation, holding their mounts by the halter straps while the noncommissioned officers galloped around them on horseback, firing their Colts in the air. The first time, they got a stampede worse than anything seen on a cattle drive. Frightened horses and men thundered away in a cloud of dust, while the few troopers who were able to hold on to the halter straps frantically tried to pull themselves up as they were being dragged.

Once most of the horses had been distributed to the troops, regimental drill took place daily and, before long, Roosevelt and his men saw real progress. One Harvard undergrad described the exhilarating mounted drills for family back home:

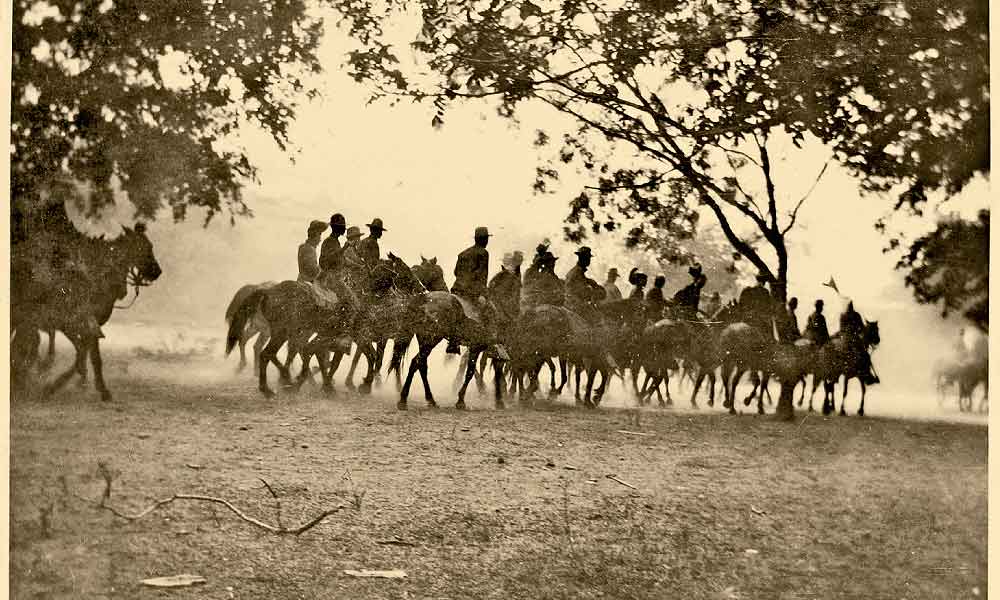

Six hundred horses galloping in column of fours is a fine wave of power. The dust lifts up so thick it is like a fog, and you can barely see the next man ahead. Half-blinded, wet with sweat, and the horses on both sides rubbing against your legs, you go tearing, galloping on. Then suddenly through the white wall of dust you see the haunches of the horses ahead sink down and a hand shoot upward with the fingers spread apart. There is a quick jam, a creaking and rubbing of leather, and they’re off again.

Out on the Town

Daily at noon, the men were given approximately one hour to rest before mess call, but instead, most of the men lined up to apply for a pass to leave camp that evening. Only about 20 passes were issued per troop each day, but two to three times as many men were requesting them. Consequently, each night, dozens of Rough Riders without passes slipped through the fence around the fairgrounds and jumped on the trolley for downtown San Antonio.

Some troopers picked up money wired from home. As the regiment had no sutler, some bought necessities in town. One trooper’s shopping list included a pound of Durham tobacco, cigarette papers, four bandannas, six pairs of socks, pocket watch, pocketknife, toothbrush and powder, soap, three towels, writing paper and envelopes, stamps and one pencil.

The men also went sightseeing, and the Alamo mission was high on every trooper’s list. Nearly all the Rough Riders visited the historic shrine. Most of the men had enlisted in a patriotic fervor, and the place where Davy Crockett, Jim Bowie, William Travis and the other Alamo defenders died for Texas independence in 1836 only amplified those feelings.

Some Rough Riders cooled off with a dip at Scholz’s Natatorium, a popular indoor swimming pool. And a meal at a good restaurant, or one of the chili stands, was always a welcome substitute for the predictable Army rations of bacon, beef, beans and potatoes. The fairgrounds groundskeeper opened a dining establishment in his residence that quickly became a favorite mealtime hangout of the millionaire recruits. They nicknamed it the Waldorf-Astoria.

San Antonio’s saloons and gambling halls were another Rough Rider magnet—and a source of frustration for the regiment’s officers. An evening of carousing didn’t make for the best soldiers in the morning. One captain wondered out loud if all the men reporting to him ill were “really sick or just tired.”

Eventually, the saloons and gambling dens cleaned the boys out of their funds. This helped somewhat with the problem of the men sneaking away from camp: it was hard to drink and gamble when you were broke.

– Courtesy Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University, 560.3-014 –

Band of Brothers

Despite their varied backgrounds, the men had bonded wonderfully. “They are now all brothers,” wrote a visitor to the camp, “and the millionaire from New York could be seen at San Antonio borrowing tobacco just as natural as the cowboy borrows a gun.”

Wood and Roosevelt were surprised and delighted with how the regiment had come together and how rapidly the drills with the entire regiment, now more than 900 officers and men, were improving.

Wood wrote to President William McKinley that the regiment’s progress was “simply astounding,” and he hoped the president would get a chance to see the “most exceptionally fine body of men.” Roosevelt also wrote to the president: “I really think that the rank and file of this regiment is better than you would find in any other regiment anywhere.”

Although Wood and Roosevelt were indeed proud of the Rough Riders, their letters also served as not-so-subtle attempts to put the regiment on an equal footing with any Regulars about to embark for Cuba. “We are ready now to leave at any moment,” Roosevelt insisted in his letter “and we earnestly hope we will be put into Cuba with the very first troops; the sooner the better.”

Roosevelt’s boasting about the rank

and file of the Rough Riders was understandable, but real proof would only come when the regiment faced Spanish guns for the first time.

This edited excerpt is taken from Mark Lee Gardner’s Rough Riders: Theodore Roosevelt, His Cowboy Regiment, and the Immortal Charge Up San Juan Hill, published by William Morrow in May 2016.