A century ago, the modern weaponry carried by the European armed forces of World War I killed thousands of young men on a daily basis. The carnage of trench warfare had never been seen on such a large scale in the history of war. In the United States, former president and war hero of the Spanish-American War Theodore Roosevelt was caught in the crosshairs of his political foe, President Woodrow Wilson, and an American citizenry that did not support the United States’ entry into the grave-filled morass of Europe’s Great War. Less than two decades earlier, Americans had had their first taste of an overseas imperial war against the Spanish Empire, thousands of miles distant in the Philippines of the Southwest Pacific, and just 90 miles offshore from Florida, in the stinking, deadly trenches of Cuba.

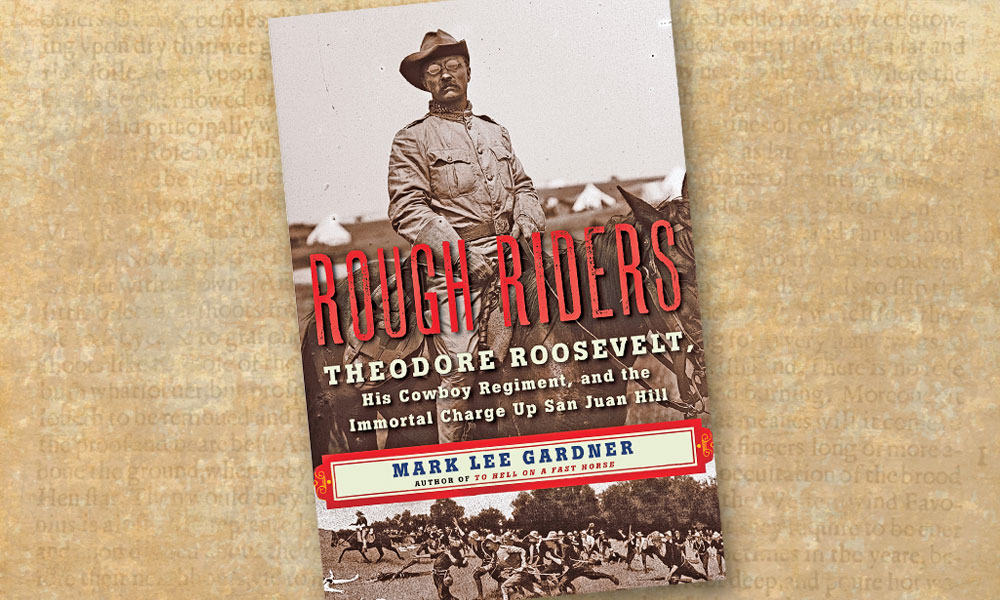

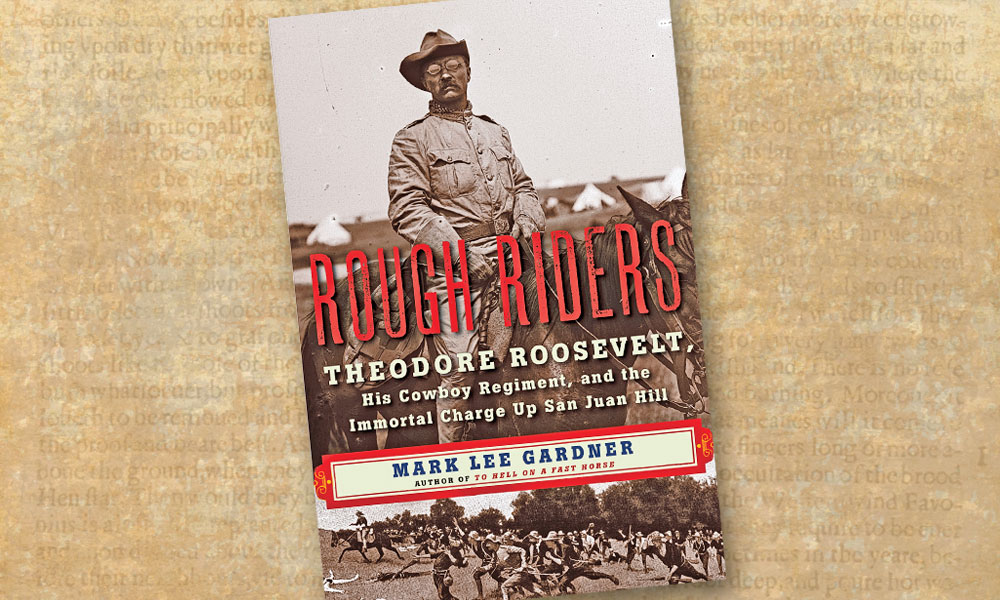

Mark Lee Gardner’s poignantly succinct Rough Riders: Theodore Roosevelt, His Cowboy Regiment, and the Immortal Charge Up San Juan Hill (HarperCollins, $26.99) illustrates Roosevelt’s rise to hero status. The rise is tempered by the brutal heat of tropical Cuba and the reality of the world’s first modern war in which machine guns and modern high-powered rifles, artillery and ammunition were tested—with deadly results—on the American and Spanish soldiers. Gardner writes, “This fight would be nothing like those old Currier and Ives prints from the Civil War, with lines of men, shoulders pressing close to shoulders.”

Rough Riders, Gardner’s third volume in what is becoming a Western biography series, is a dramatic hero’s tale as compared to his chronicles of Billy the Kid and the James-Younger Gang in To Hell on a Fast Horse and Shot All to Hell, respectively. When asked why he chose to write about Roosevelt and the Rough Riders, Gardner said, “The story of the Rough Riders is in many ways a Western story; most of the regiment was raised in the American Southwest.” Gardner’s study of the heroic actions of the future president and his loyal soldiers is a familial if not sociological extension of the citizenry of the Southwest and Midwest he wrote about in his earlier books.

“The Rough Riders was composed of rich men and poor men, cowpunchers and tennis champions, American Indians and Ivy Leaguers (oh, and a murderer or two).” The populism of equality that Gardner brings to his treatment of Western outlaws—and their extended families and foes—is equal to his populist interpretation of the Rough Riders and Roosevelt, who seized destiny’s opportunity to become America’s first modern military hero, and as the fates would have it, first modern president of the 20th century. As the Colorado author notes, “In his farewell speech to his regiment, Roosevelt said, ‘No man asked a quarter for himself, and each one went in [to the war] to show that he was as good as his neighbor. That is the American spirit.’”

Gardner’s Rough Riders is a timeless story of how the fortunes of war and one man’s decision to serve with distinction—above and beyond the call of duty for honor and country—can change the course of history. “What’s important about remembering Roosevelt leading his men

to victory is that it was no myth,” says Gardner. “He did indeed show incredible bravery. He did indeed lead his men and a number of Buffalo Soldiers and white regulars in a charge up San Juan Hill. And he earned unquestionably, the Medal of Honor he was denied after the war but awarded posthumously in 2001. When it comes to war heroes, TR was the ‘real deal.’” And so is Gardner’s Rough Riders. It’s a classic, inspiring biography of a true American hero, in an era when America is in desperate need of real heroes.

—Stuart Rosebrook