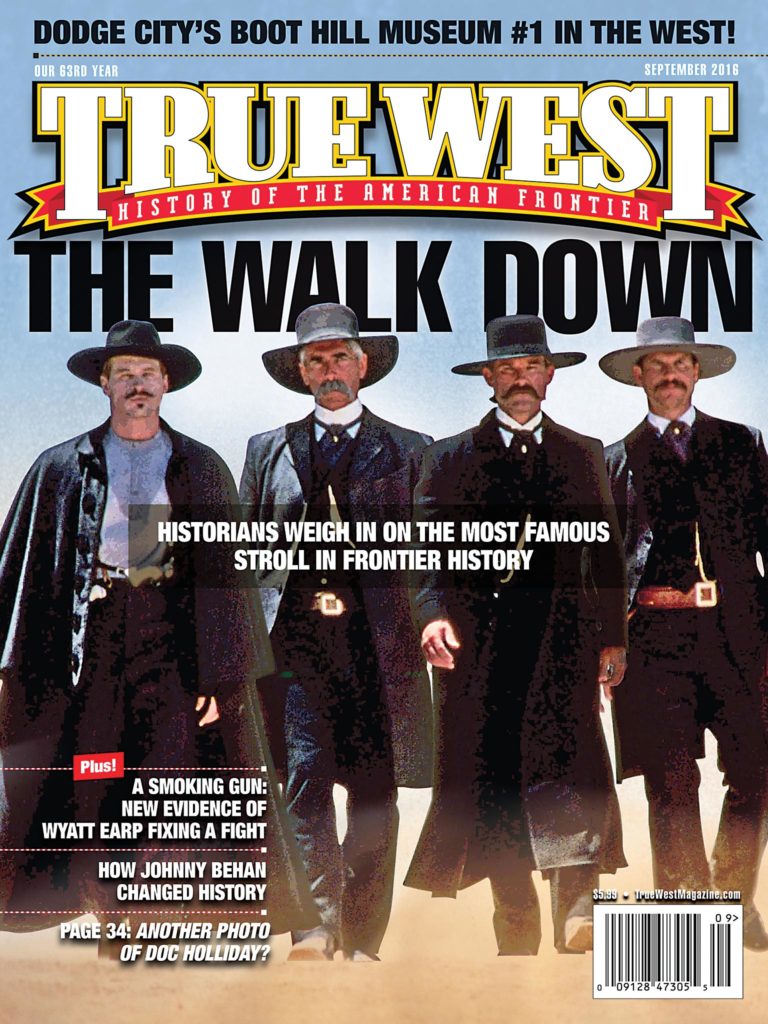

Did Wyatt Arrest Ben Thompson?

This alleged arrest has driven researchers batty for decades. The most famous account appears in Stuart Lake’s Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal.

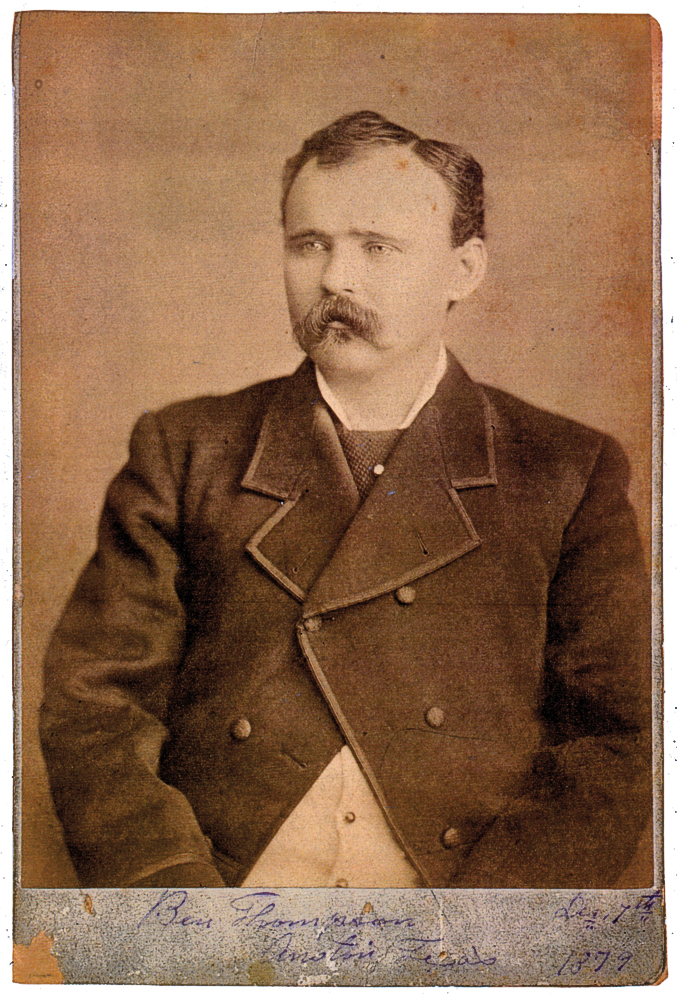

Today, Ben Thompson’s name is remembered only by a handful of Old West history buffs, but in his day, Ben was far better known on the frontier than Wyatt Earp. English born and Texas bred, Ben was sort of the Lou Gehrig or Jimmy Foxx of gunfighters in the 1870s, with James “Wild Bill” Hickok generally accorded the status of Babe Ruth. The two were champions of their respective regions: Ben having fought in the Confederate army, Hickok, in the Union. The two legends never faced each other, but since Lake was grooming Wyatt to eclipse Hickok, he gave Wyatt the confrontation with Ben that Hickok never had.

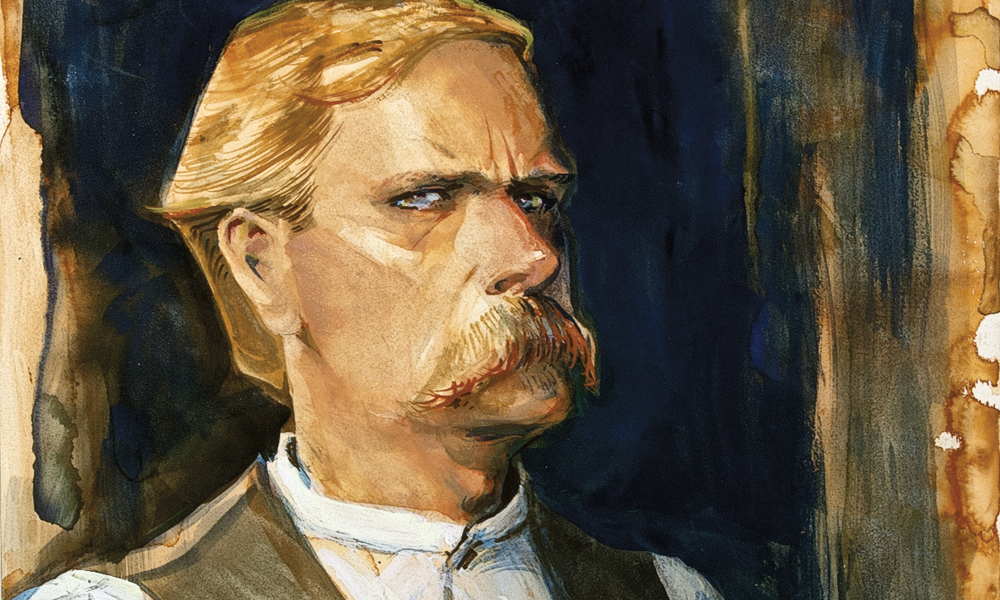

– All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell; Ben Thompson photo courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

Lake’s story has Wyatt, a complete unknown, riding into the thriving cattle station of Ellsworth, Kansas, in 1873, just after Ben’s brother Billy killed the county sheriff, Chauncey “Cap” Whitney, in what was probably an accident stemming from Billy resisting arrest.

The 25-year-old, unarmed Wyatt, appalled that no arrests had been made, sarcastically remarked to the mayor, “Nice police force you have got.” The mayor challenged Wyatt to take the job; Wyatt borrowed two gun belts and Colts, and walked down the main street to confront Ben.

“What do you want, Wyatt?” Ben asked.

“I want you, Ben,” Wyatt replied.

“I’d rather talk than fight,” Ben said.

“I’ll get you either way,” Wyatt said.

Curious thing about Ben’s first question: he addressed Wyatt by his first name, implying that he knew Wyatt from somewhere.

In any event, Ben shrugged and decided to take his chances in court, where, being a wealthy Texan and a cattleman, he would get preferential treatment. He was correct—the judge fined him $25 for his role in shooting Whitney. The official charge was “disturbing the peace.”

Wyatt, the spiritual father of Dirty Harry, tossed his badge away in disgust and walked off. “Ellsworth,” he said, “figures sheriffs at $25 a head. I don’t figure this town’s my size.”

Researchers have done everything but rip up the floorboards of Ellsworth’s sidewalks in their attempts to discover any truths in Lake’s story. I don’t know why they have persisted. Nothing has ever been found to support it—not in court records, newspapers or eyewitness testimony.

One intriguing nugget does suggest an encounter between Ben and Wyatt that has gone curiously unheeded by researchers. It is published in John Flood Jr.’s manuscript, Wyatt’s first attempt at a ghost-written biography.

Ben was indeed arrested in Ellsworth after his brother killed Sheriff Whitney, not by Wyatt, but by local deputy Ed Hogue, who, ironically, would later be arrested by Wyatt for a misdemeanor in Dodge City. About a year later, Wyatt was in Wichita, where he got into a scrape with some Texans who, apparently, were friendly with Ben. The cause of the altercation is unknown, but, according to the manuscript, Wyatt told them, “Go back uptown and ask Ben Thompson. He was in Abilene, he will tell you.”

Nothing more is known about the incident or whether or not the angry Texans did go uptown to confirm Wyatt’s story—whatever it was—with Ben. Presumably they did, and the problem, whatever it was, got resolved.

Wyatt’s words were not boastful. He didn’t seem to be suggesting he had arrested Ben in Ellsworth, Abilene or anywhere else. But Wyatt was using Ben as a sort of character reference, which implies some knowledge and at least a modicum of respect between the two men.

Back in Ellsworth, could Wyatt have intervened and perhaps even defused a potentially explosive situation by talking Ben into appearing before a judge and paying a small fine? Perhaps so. It wouldn’t have been the only time in Wyatt’s life that he had used a cool head to avoid trouble, which, after all, was the main job of a peace officer in a cowtown.

Did Wyatt Hold Back a Mob to Save Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce?

Yes, said Stuart Lake in his colorful 1931 Wyatt Earp biography.

No, say most modern historians.

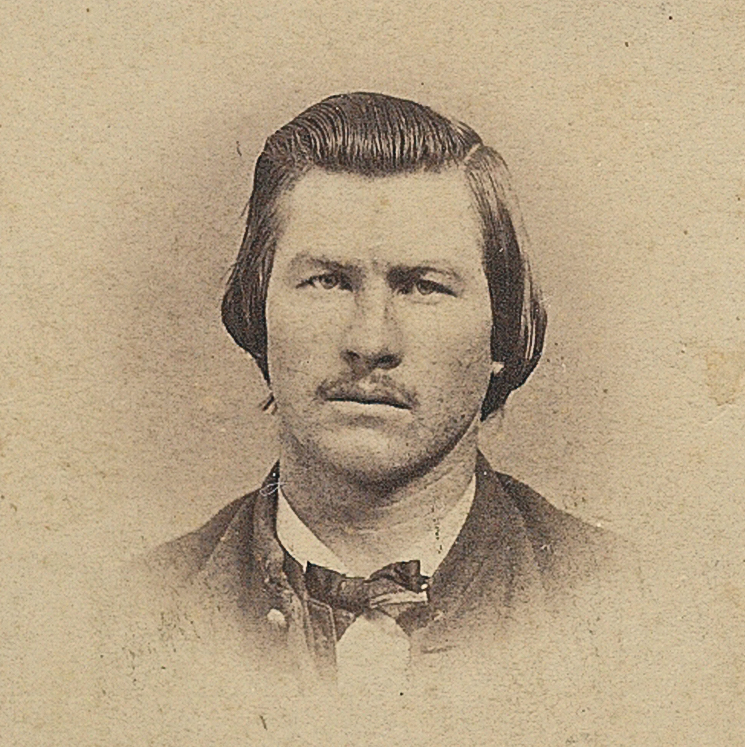

On January 14, 1881, W.P. Schneider, an engineer living in Charleston, Arizona, stepped into a restaurant to warm his hands. Mike O’Rourke, an 18-year-old small-time gambler and troublemaker referred to as Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce—he apparently had a habit on betting on the deuce when playing faro—made some sarcastic comment to the effect of, “I thought you never get cold.” Schneider dismissed the teenager with a chilly, “I wasn’t talking to you.”

O’Rourke, swift to anger, threatened to kill Schneider. O’Rourke was seldom as good as his word, but this was one of the few times that he kept his promise. He ambushed Schneider and murdered him.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

No one knows what bad blood had passed between the two men that brought matters to such a conclusion, but the Deuce, who could properly be labeled as one of the tinhorn gambler element old-timers talked so much about, was immediately taken into custody. The local miners, among whom Schneider was popular, were outraged; calls to lynch the killer circulated.

Charleston’s Constable George McKelvey was smart enough not to try and make a dash all the way to Tucson with his prisoner. He headed instead for Tombstone, but made about half the distance when a mob of miners closed in on his wagon.

McKelvey, and certainly O’Rourke, had the good fortune that Wyatt’s brother Virgil was in the area, exercising Wyatt’s horse, Dick Naylor. Virgil ordered O’Rourke to swing onto the horse’s back and ride to Vogano’s Saloon in Tombstone, where another Earp brother, James, was tending bar.

Before leaving Charleston, McKelvey had the presence of mind to telegraph Tombstone Marshal Ben Sippy to gather several armed men to prepare for the ride from Tombstone to Tucson. Yet the ugly mood had spread to Tombstone’s miners. Before long, a throng of townspeople, several of them armed, advanced on the wagon Sippy was preparing for the journey.

Per Lake’s account, “Five hundred blood-lusting frontiersmen”—John Ringo among them, by the way—poured into Allen Street as Virgil and Morgan, another Earp brother, got Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce to safety.

In Frontier Marshal, Wyatt stood close to the curb, shotgun in the crook of his right arm, cautioning the front ranks of the mob: “Don’t fool yourselves. That tinhorn’s my prisoner, and I’m not bluffing.”

Legend—or at least the legend created by Lake—states that the crowd dispersed.

Wyatt, though, wasn’t the marshal or an officer of any kind and had no authority to call the Deuce “my prisoner.” A modern debunker, Andrew Isenberg, in his 2013 book, Wyatt Earp: A Vigilante Life, points out the absurd histrionics used to highlight the incident in accounts by Wyatt researchers Forrestine Hooker, Flood Jr. and Lake, which, he says, “the authors all present as the most important episode in Wyatt’s career as a Tombstone law officer prior to the [O.K. Corral] gunfight.” Eisenberg also points out the similarity in the three accounts: “It’s likely that Flood drew from Hooker and, later, Lake from both.”

Much of the writing on the Deuce affair is pretty silly. Flood has it, “[Wyatt] was mighty, and he beheld them beneath his hypnotic gaze,” and that Wyatt vowed to kill 10 men if the mob rushed him.

To bolster the argument that Wyatt did not hold back a mob, Isenberg points to James Covington Hancock, who, in his memoir, claimed to be present when Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce arrived in Tombstone. “When Johnny was brought in, it naturally attracted a bunch of idly curious who gathered around to see what was going on,” Hancock stated. “Just a bunch of harmless ‘rubber-necks’—I was one of them myself—no one armed and there was no demonstration of any kind. They put him in the buggy and drove off towards Benson as quietly as if they were going to a picnic.”

Debunkers maintain Hooker, Flood and Lake got it wrong. They cite the January 27 issue of The Tombstone Epitaph, which describes Ben Sippy as “cool as an iceberg, he held the crowd in check.” Sippy, Cochise County Sheriff John Behan and Virgil Earp are singled out for praise. Wyatt isn’t mentioned.

Isenberg concludes that the mob claim “was not the only time [Wyatt] appropriated the accomplishments of someone else as his own.”

Wyatt also was not mentioned as being involved in the incident in the oft-quoted journal kept by Tombstone resident George Parsons. Walking along Allen Street that fateful night, Parsons came upon the mob, watched the proceedings and later recorded the event in his journal:

“The officers sought to protect [O’Rourke] and swore in deputies—themselves gambling men—to help. Many of the miners armed themselves and tried to get at the murderer. Several times, yes a number of times rushes were made and rifles leveled causing Mr. Stanley and me to get behind the most available shelter. Terrible excitement. But the officers got through finally and out of town with their man bound for Tucson.”

Hancock’s account is the easiest to dismiss. He never mentioned witnessing the incident until 50 years after the fact, and then his story doesn’t square with anyone else’s.

Why, though, didn’t the Epitaph or Parsons’ journal mention Wyatt? Probably because Wyatt wasn’t an officer at the time. Parsons mentions no officer by name, but does say that deputies were sworn in—Wyatt and Virgil were among those deputies. The Epitaph probably left out Wyatt’s name for a simple reason: the newspaper was plugging its candidate for town marshal, Sippy.

Just because the Wyatt researchers’ accounts were embellished, however, does not mean that the confrontation they described didn’t happen. As we see over and over in the Wyatt story, something was alleged to have happened, was later debunked and then, after closer examination, was revealed to have happened after all.

What Isenberg neglects are the eyewitness accounts placing Wyatt at the forefront, namely by sometime-Wells Fargo agent Fred Dodge, Epitaph editor John Clum and Billy Breakenridge.

Dodge not only credited Wyatt with holding off the crowd, he also claimed Behan and Sippy stood off to the side and did nothing. Clum, in his later recollections, gave Wyatt the lion’s share of the credit and criticized Sippy, all but admitting that his newspaper had fudged the story when it first reported it.

Parsons also added in his two cents worth. In a 1903 article for the Los Angeles Morning Review, Parsons gave Wyatt almost full credit for stopping the mob. One cannot accuse Parsons of riding a legend—the first nationally distributed profile of Wyatt, Bat Masterson’s story for Human Life magazine, was still four years away. One also cannot write his story as the hero worship of an old man—Parsons was not yet 50 when he wrote the story for the Los Angeles paper.

Why, then, didn’t Parsons mention Wyatt in his journal in January 1881? The simplest answer is probably the correct one: he wasn’t focused on Wyatt at the time.

For some strange and never explained reason, the strongest support for Wyatt’s role in the Deuce standoff was Behan’s own deputy, William Breakenridge. In his 1926 book, Helldorado, Breakenridge mentions Wyatt—and only Wyatt—at the incident. Wyatt, he wrote, “stood them off with a shotgun and dared him to come and get him. It didn’t look good to the mob.”

Here’s the real oddity: Breakenridge didn’t mention his boss, Sheriff Behan, at all.

Of all those who claimed to witness the clash of police and citizens that day, Breakenridge is surely the one least likely to present a pro-Earp account.

The later accounts of Wyatt’s actions in saving Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce are definitely overblown and melodramatic. But when the hagiography is stripped away, some hard nuggets of truth remain: Wyatt was there, and O’Rourke never got lynched by that angry mob.

Were Wyatt and Sadie Marcus Lovers in Tombstone?

The emergence of Josephine Sarah Marcus in the Tombstone story was the real impetus for a revival of interest in the Wyatt Earp saga. In the space of a couple of decades, she went from someone given just a single mention in Frontier Marshal to Tombstone’s “Helen of Troy,” the supposed cause of hostility between Wyatt and Sheriff John Behan.

Stuart Lake, concluding his research in 1930, actually saw Josie—or Sadie, as her family called her—as the center of the story. “Johnny Behan,” Lake wrote to his editor at Houghton Mifflin in 1929, “was a notorious ‘chaser’ and a free spender making lots of money. He persuaded the beautiful Sadie to leave the honky-tonk and set her up as his ‘girl,’ after which she was known as Sadie Behan.” He added, “In the back of all the fighting, the killing, and even Wyatt’s duty as a peace officer, the impelling force of his destiny was the nature of his acquisition and association in the case of John Behan’s girl. That relationship is the key to the whole yarn of Tombstone. Should I or should I not leave that key unturned?”

Probably because Josie threatened to sue if Lake’s story did not meet her approval, Lake decided against turning the key. She succeeded in keeping herself out of Wyatt’s story—for a while, at least.

How much was there to the relationship that Lake defined as “the key to the whole yarn of Tombstone?” After Tombstone, the couple moved together to California, and Wyatt was with Sadie for the rest of their lives. But what about their Tombstone story?

Historians, scriptwriters and novelists must have been surprised to find at the end of their research that nothing supports the notion of any kind of relationship between Wyatt and Josie while they lived in Tombstone, Arizona. Nothing—not a letter, not a newspaper item, not a single page of any memoir written by anyone who was in or around town during the Earp-Behan years—mentions Wyatt and Sadie being together.

The publication of Frank Waters’ The Earp Brothers of Tombstone in 1960 brought out this idea, by implying that Wyatt was often seen on the town with the dazzlingly dressed Marcus on his arm. But we now know that the book’s claims are fraudulent, and the discovery of Waters’ original manuscript at the University of New Mexico, titled Tombstone Travesty—which differed from the published version—merely confirmed that, whatever knowledge they had of each other in Tombstone, Josie and Wyatt certainly weren’t having an affair.

Tombstone was big for a frontier money camp, but it wasn’t that big. Somebody—a family member, one of Wyatt’s enemies or just plain gossipy people like Parsons—would surely have noticed.

Allen Barra is the author of Inventing Wyatt Earp: His Life and Many Legends. He writes about sports for The Wall Street Journal and is a contributing writer for American History Magazine and The Daily Beast. His last book, Mickey and Willie: The Parallel Lives of Baseball’s Parallel Lives, was nominated for the Pen Award for Literary Sportswriting.