Clint Walker never really made sense; he was six feet, six inches tall and made average men look and feel like Mickey Rooney standing next to him.

He was also incredibly good looking and had a baritone voice a few degrees east of Gregory Peck or west of Fess Parker.

Walker was born to play mythical figures like Paul Bunyan or maybe Big Bad John, the coal miner who saves everybody before he dies in Jimmy Dean’s classic song: “Every mornin’ at the mine you could see him arrive / He stood six foot six and weighed 245 / Kinda broad at the shoulder and narrow at the hip / And everybody knew ya didn’t give no lip to Big John.”

The song also describes John as “kinda quiet and shy,” which likewise describes most of the characters Walker portrayed, both on TV and in the movies. These men had to work to get a thought up and out of that mountainous torso. If words were wood, Walker’s characters couldn’t fuel a fire big enough to heat soup.

All of these attributes panned out in his favor. For a guy who was working security at the Sands hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada, just a short time before he got his first big show business break, he was a fine actor who did exactly what was required of him, and he did it well.

Walker played only two insignificant parts in movies before he landed the lead in what is now considered to be a cornerstone series in TV Westerns history. Cheyenne debuted the same season, in 1955, as Gunsmoke and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp. These three Westerns essentially created the adult TV genre.

Cheyenne, which was Warner Brothers’ first successful TV series, had many of the studio’s greatest scripts on tap. It was as if Walker was acting in the Warner repertory company, one week doing an adaptation of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, the next week, To Have and Have Not.

Walker deserves credit for making Cheyenne a success, both on the screen and behind it. When the show, which lasted through 1963, hit, Warner was quick to give Walker side work in features (he even cut an album).

Luckily for Walker, the studio teamed him with veteran director Gordon Douglas and hired strong scriptwriters, like Burt Kennedy (who was, at the same time, working with Director Budd Boetticher and actor Randolph Scott) and Leigh Brackett (the screenwriter of Howard Hawks’s 1959 classic Rio Bravo).

The Walker/Douglas team made 1958’s Fort Dobbs, 1959’s Yellowstone Kelly and 1961’s Gold of the Seven Saints, all solid, intelligent Westerns now available as part of the Warner Archive DVD series.

Fort Dobbs is a nicely-crafted film with a story that falls neatly into the Louis L’Amour/Hondo subgenre, where rugged men, at home under the sky, find a connection to a youngish widow and her spunky son. The film also features a charming bad guy in Brian Keith, who acts like he just walked out of a Boetticher picture.

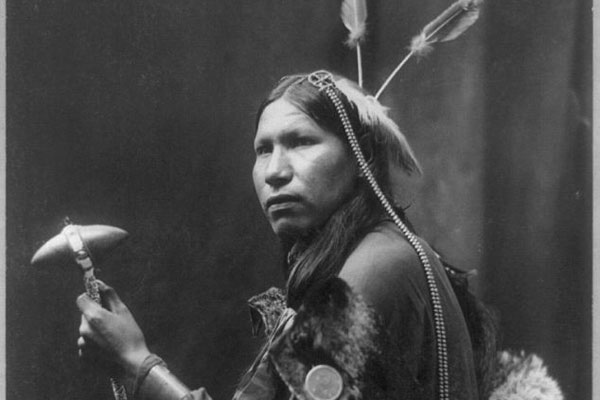

Yellowstone Kelly is a fanciful movie-fiction idea of a real-life character who earned his fame scouting for the U.S. Army on the Yellowstone River in the 1870s. Warner packaged the picture with another one of its TV actors, Edd “Kookie” Byrnes, who wants to apprentice under Kelly. Just when the two are about to turn into the Liver-Eatin’ Johnson version of Fred and Ethel Mertz, a wounded Arapaho princess gets dropped in their laps and the story heats up. Byrnes is better than just okay, Walker is just fine as the grumpy bachelor frontiersman and the girl ain’t ugly, as Kelly says in the film.

The most intriguing of the three movies is the one Warner released first on DVD yet was the final collaboration between Douglas and Walker, Gold of the Seven Saints. This is a nice odd-couple pairing of Walker, who is a tad looser here than he was in the prior two movies, and Roger Moore, who sports a Lucky Charms Irish accent as he plays Walker’s partner in adventure. Even though perennial heavy Robert Middleton goes into scene chewing outer space with his attempt to play a hideously jovial Mexican rancher/crook, this film offers a lot of great material. In essence, it lit the fuse that led to The Professionals and, later, The Wild Bunch.

All three of these pictures were shot primarily in John Ford Country, in southern Utah. Two are black-and-white, while Yellowstone Kelly is in color.

Walker was far from finished when he pushed himself away from the Warner table and started making more pictures, like, famously, The Dirty Dozen. He greatly enjoys meeting his fans at various Western film festivals. His health is depressingly perfect. And, just between us, he’d really like for someone to give him a piece of a decent movie.

True West: How did you like working with Director Gordon Douglas?

Clint Walker: I did three movies with Mr. Douglas: Fort Dobbs, Yellowstone Kelly and Gold of the Seven Saints, with Chill Wills and Roger Moore. But I liked Gordon; I had a lot of respect for him as a director and especially as an outdoor director. We worked very well together.

What kind of a director was he?

He was a man’s man, and he didn’t mind working hard. He didn’t mind being out in the sun, the weather. He knew what he wanted, and he didn’t give up until he got it. He was certainly a professional, but I always thought he was very likable.

After working together on three pictures, could you say you became friends?

Oh, yeah. We were good friends. We got along very well. I even—I had my motorcycle with me on one of the pictures. One day he was wondering about a certain site, and I said, “Well, hop on my ‘cycle [rhymes with “pickle”] and we’ll go take a look,” and we did. I felt very, very fortunate to have him for a director. Some of the stuff was pretty rough, but that’s what makes good pictures.

What kind of rough?

Well, we’d go up in the rocks, and we’d do some climbin’. We did some climbin’! It was hot, it was dusty and it was dirty.I wanted to look as authentic as I could, so I just wore the same old shirt. If it got dirty, it got dirty. But he didn’t mind goin’ to rough locations. He didn’t mind walkin’ or climbin’ or whatever he had to do. Again, I always thought of him as a man’s man.

How did you get along with Chill Wills?

He was pretty well up in years there, but he did a magnificent job. I was amazed. He didn’t mind roughin’ it, which he had to do quite a bit of on that picture.

Were those three pictures shot around Moab, Utah?

Yeah! Oh boy, that grand Arches National Park! I don’t think you’d find a more spectacular place.

Is it true you own some land around Kanab, Utah?

Yeah, I do. I’ve got 10 acres. I won’t say exactly where, but we want to build a home there—we want to move there. I’ve got a lot of sandstone around me and a big mesa. When I first came to that part of the country to do Fort Dobbs with Virginia Mayo and Brian Keith, I guess I fell in love with the country. I love the mountains and the pines and the rivers and all of that, but I also have a love for the high desert country.

Is it nice making films in those kinds of locations?

That’s what I prefer. I like the outdoors stuff. I guess that’s why I always felt at home doing Westerns or anything of that nature.

How did you make the transition from security work in Las Vegas to movie work in Los Angeles?

I was in Vegas working as a deputy sheriff at the first Sands hotel. I was there about a year and a half, I guess, and we had a lot of the stars who’d come there to perform at the Copacabana Room. One of— My gosh, I can’t even think of his name, the red-haired actor. Big guy. Used to wear red socks a lot. [Laughs.] Anyway, he came up to me one Saturday night in the casino and said, “I don’t know if you’d be interested or not, but there’s one of Hollywood’s biggest agents here, and he’d like to talk to you.” So we did, and it was Henry Wilson. I guess I didn’t seem all that interested, but he said, “I can’t promise you anything, but if you’re interested at all, you’ll have to move back to Hollywood where we can do interviews.”

I thought about it for a couple of months. I thought, “Well, what am I going to get here, just wearing a gun and a badge? Maybe get shot.” So I quit my job, and I packed up and went to Hollywood.

When you first started acting in Cheyenne, coming out of Nevada, how did you feel?

I felt pretty comfortable right away. The reason being, I think, is, you know, Cheyenne was always wearin’ a gun. A lot of times I was playin’ a sheriff. Of course that’s what I had been doin’ in Las Vegas as a deputy sheriff. Before that, in Long Beach, I worked as a security guard on the waterfront and as a bouncer in the nightclubs. So I kind of felt right at home with all that. As a bouncer I never hit anybody; I had a name for being able to handle people without hurting them, and I took a lot of pride in doing that. I’d always try to talk ‘em out of trouble if I possibly could.

Was it enough to just look tough?

Wellll—no. [Laughs.] There were times when I had to get physical. I didn’t have a choice. But I’d say, “Look, pal, I’m just trying to make a living; I’ve got a wife and child to support. This is nothing personal, but if the boss says you have to go, you have to go. Now I’d realllly appreciate it if you left on your own two feet. You won’t be embarrassed, and I won’t be, and I can let you come back next week if you want to.” Sometimes they’d go, and sometimes they wouldn’t.

How was Vegas?

Vegas was easy. Let me put it this way: a lot of times, when people come to bars and nightclubs, they’re not happy. They’ve had a fight with their wives or girlfriends or maybe their best buddy. They’d be in a foul mood, and once they got enough drinks in them, they’d start getting’ mean. There are three kinds of drunks: ones who get mean, ones who get funny and ones who just go to sleep. [Laugh.]

But Vegas was easy, because people came there to have fun. They didn’t come there to get mad. I spent more time looking for pickpockets or people who were trying to jimmy the slot machines. So that was pretty easy, and more fun, because I’d get to see a lot of stars who would come there to perform.

Is it true that you frequently scrapped with Warner Brothers during your Cheyenne years?

Warner was always quality-oriented, and I was always grateful for that. That’s part of the reason I think the Cheyenne years were as good as they were. Good directors, good writers. But of course I was always looking for any kinda things that didn’t make sense or where there were holes in the script or whatever, and sometimes I would hold them up…. They’d say, “Well, Clint, how many people are gonna notice that?” And I’d say, “Enough to make it worth correcting.” I think, because of that, the shows were a mite better than they might have been.