By 1880, the great herds of buffalo—estimated at 60 million in America—were all but gone, leaving behind them a dismal story of human greed and shortsightedness.

William T. Hornaday of the New York Zoological Society traveled throughout the West in 1889 to conduct a census of the remaining buffalo. He found only 541.

An unlikely hero in the person of a Flathead Indian named Samuel Walking Coyote did a great service for the buffalo in the course of trying to save his own hide. Sam paid a prolonged visit in the early 1870s to Montana’s Blackfoot tribe, which allowed warriors to have more than one wife. Although he was already married to a Flathead woman, Sam tied the knot with a lovely Blackfoot girl. In time he began to pine for his home, but he had to take the Blackfoot wife home with him to avoid making her many male relatives angry. Sam knew the Flathead tribal elders would not be happy at his return with wife number two. The Flatheads, influenced by the Jesuits, practiced strict monogamy.

This circumstance caused Sam Walking Coyote to take gifts to his tribal leaders in hopes of avoiding punishment. He captured four young buffalo calves, two bulls and two heifers, and he took them along when he returned home. The tribal elders did not wait to hear Sam’s reasoned pleas when they discovered he had taken a second wife. They flogged him immediately and cast him out of the tribe.

Over the next few years, Sam’s buffalo herd increased. In 1883 the animals caught the attention of Michel Pablo, the son of a Spaniard and his Blackfoot wife, reportedly born circa 1836. Pablo was a shrewd businessman and saw an opportunity in the small herd. With his partner Charles Allard Sr., Pablo bought Sam’s herd, which had increased to 13 buffalo, and turned them loose on the 1.5-million acre Flathead Reservation, along the Jocko and Pend d’Oreille Rivers in Montana, to forage for themselves. Buffalo are good at this. They went forth and multiplied.

In 1906, the U.S. government decided to open the Flathead Reservation to settlers. The decision spelled the end for Pablo’s free-ranging buffalo herd. Allard had died in 1896, and his share of the herd, which by that time numbered about 300, was scattered among his heirs, but Pablo’s share continued to multiply. Pablo did his best to interest the government in acquiring the buffalo and setting up a refuge where they could be protected from the sad fate of their ancestors, but the government was not interested. Pablo finally accepted an offer from the Canadian government, which needed the animals to restock an area in Alberta where buffalo had roamed in the early part of the century. The Canadians offered Pablo $250 a head, and he had little choice but to accept.

“Many people today, while appreciating the fact that Samuel Walking Coyote, Michel Pablo, Charles Allard and Andrew Stinger were the ones who saved the buffalo from extermination, question their motives,” said Tony Barnaby, Pablo’s son-in-law. “Some say that the plan was to build up a vast herd that later could be sold at a great profit.”

The profit motive was not true, Barnaby argued. “Michel Pablo did not consider a buffalo as just a great, shaggy beast of the plains, but rather as symbolic of the real soul of the Indians’ past.”

Regardless of Pablo’s feelings for the animals, the contract was signed and the roundup began.

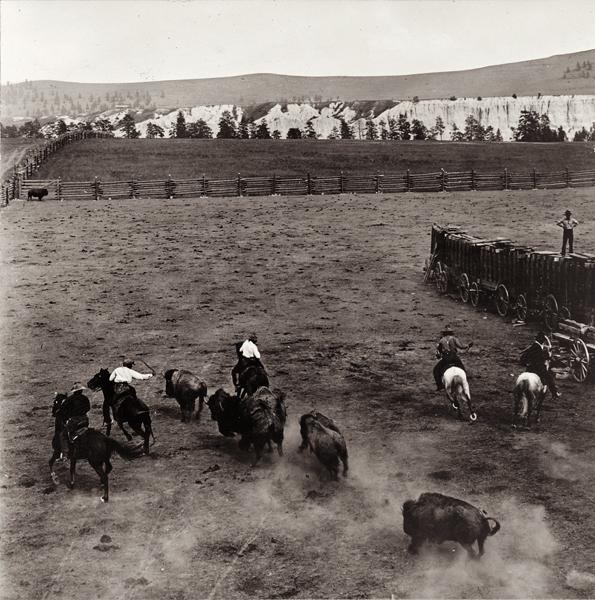

At the time of the 1907 roundup, Pablo was 71 years old. Well over six feet tall, with a shaggy head of white hair and an impressive white handlebar mustache, he still spent most of his time on horseback. Pablo was wise in the ways of buffalo and knew the roundup would not be a cakewalk. He hired a crew of the best riders in the area, many of them Indians. Hours of hard riding ensued, after which the “buffalo boys,” as Pablo called them, had assembled a fair-sized herd. Surveying the shaggy animals, Pablo made a fateful decision; he decided to drive the entire lot at once to the Ravalli Railroad Station.

The buffalo were irritated after a day of being chased by men on horseback. When the men attempted to drive them off their home range, they rebelled. First one group and then another made a break for home. While the cowboys chased the runaways, another group of the beasts took advantage of the distraction by racing off in another direction. By the time the crew reached the railroad station, only 30 buffalo were left in the herd. Pablo must have sighed with relief when these galloped into the corrals at the station. Inside the corrals, Pablo had built a wing which would funnel the animals right up into the waiting railroad cars. Led by a huge bull, the buffalo trotted up the ramp, crashed through the opposite side of the boxcar and stampeded off through the valley to freedom.

After this first unhappy attempt to gather the herd, Pablo put off further roundups for a year. During that time, he built a new set of pens from much stouter material. A steep cliff formed the back of the pens. But the buffalo boys had hardly chased the last animal through the gate of this new pen before the first one scaled the cliff like a mountain goat, pausing when he reached the precipice to look down at the crew below and snort his contempt. The others followed.

An impregnable back fence was added to the pens, and the buffalo boys went out again. They found a small bunch nearby and drove them into the corral where they milled anxiously, sizing up the wall of two-by-six planks spaced six inches apart. After a couple of rounds, a bull inserted his horns through the space under the top plank and lifted it from the posts, tossing it over his shoulders like a toothpick. Backing up a pace or two, he led the others in a coordinated assault on the fence and a gleeful rush to freedom.

By now, word of Pablo’s buffalo battles had spread, and newspaper reporters gathered with their notebooks and cameras to record the outcome for posterity. Some of them seemed to be rooting for the buffalo. One of those who came to watch was famed cowboy artist Charles M. Russell.

The addition of a crowd of folks unschooled in the behavior of wild buffalo did nothing to improve the smoothness of the operation. The buffalo, understandably, were more agitated than ever and thought nothing of charging surprised bystanders with intent to kill.

Russell and photographer N.A. Forsyth once positioned themselves inside the wing fence leading into the pens in order to get head-on photos of a charging herd. Appreciating the view for a moment too long, Russell leapt over the fence inches in front of a pair of deadly horns; the photographer saved himself by dangling from the branch of a tree just above the stampede, where his pants and his dignity were shredded by passing horns. Russell’s painting A Close Call captured the photographer’s miraculous escape from death. Forsyth’s camera, abandoned on the ground, did not fare so well.

After all this human harassment, the herds of buffalo kept a constant eye on the horizon, looking for riders. Unlike cattle, the buffalo didn’t gather into a cohesive group for protection in the face of danger. Instead, when riders charged down upon them, they scattered in all directions like a rack of pool balls before the cue of Minnesota Fats. Pablo called for reinforcements. He offered riders the unheard-of sum of $5 a day to help catch and ship the buffalo. Ranches in the area had to get by with skeleton crews as their cowboys congregated for the next phase of the buffalo roundup.

Determining that the better part of wisdom might be to leave the renegade bulls behind and concentrate on cows and calves, Pablo and his buffalo boys began to make slow but steady progress. In July 1907 Pablo sent a trainload of 215 cows and calves on its way to Canada, followed by 180 more in October. With newfound confidence, Pablo predicted that he would be able to fulfill his contract in 1908.

Unfortunately, most of the animals remaining were bulls, and they had scattered across the reservation in small, wary groups. In 1909 the crew corraled and shipped another 208 animals, but a few of the bulls smashed their way through fences and railroad cars so many times that Pablo instructed his riders to leave them alone.

By 1912, with just 100 bulls left, Pablo capitulated. He was 76 years old and worn out from his five-year tussle with the beasts. Two years later, he died. The remaining bulls were allowed to live out their lives on the reservation under the watchful eye of the newly-formed American Bison Society.

From the beginning of the Great Buffalo Roundup, the fearsome resistance of the buffalo captured the imagination of Americans who were distressed that the last large herd would soon roam free in a new national park in Wainwright, Alberta. William T. Hornaday convinced Theodore Roosevelt that a plan to preserve the species in America was needed. In 1905, the American Bison Society met for the first time, with Hornaday as president and Roosevelt as honorary president. From small private herds, the group gathered enough animals to stock a few national parks and preserves. Pressure from the public and Hornaday finally convinced Congress in 1908 to purchase 18,000 acres of the Flathead Reservation in Montana for a National Bison Range, which is now a part of the National Wildlife Refuge System.

On a self-guided tour of the National Bison Range, visitors drive the 19-mile Red Sleep Mountain loop over steep roads and switchbacks. The Mission Mountains loom in the distance, providing some of the most beautiful scenery in the Northwest, as the magnificent bison graze unconcerned nearby. Administrative officer Delon Weaselhead, a Pend d’Oreille Indian, manages the herd of 300-500 buffalo with the same spirit as his ancestors. He, too, sees them as the “real soul of the Indians’ past.”

Where to see Wild Buffalo in the West:

• National Bison Range (near Ravilli, MT)

• Yellowstone National Park (MT, WY, ID)

• Henry Mountains (near Richfield, UT)

• Grand Teton National Park (WY)

• Teddy Roosevelt National Park (ND)

• Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge (near Lawton, OK)

• Catalina Island (CA)

• Rocky Mountain Arsenal Nat’l Wildlife Refuge (near Denver, CO)

• Wind Cave National Park (SD)

• Badlands National Park (SD)

• Custer State Park (near Rapid City, SD)

• Bear Butte State Park (near Sturgis, SD)

• Sandsage Bison Range and Wildlife Area (near Garden City, KS)

• Big Basin Prairie Preserve (near Dodge City, KS)

• Maxwell Wildlife Refuge (near Canton, KS)

• Delta Junction Bison Range (Delta Junction, AK)

• Farewell Herd (Farewell, AK)

• Chitina and Copper River Herds (Chitina, AK)

• Neal Smith Nat’l Wildlife Refuge(near Des Moines, IA)

• Antelope Island State Park (near Layton, UT)

• Fort Niobrara Nat’l Wildlife Refuge(near Valentine, NE)

• Tallgrass Prairie Preserve (near Pawhuska, OK)

• House Rock Wildlife Area (near Jacob Lake, AZ)

• Raymond Ranch Wildlife Area (near Flagstaff, AZ)

• Blue Mounds State Park (near Luverne, MN)

Martha Deeringer writes freelance articles and children’s fiction from the back porch of her home on a central Texas cattle farm.

Photo Gallery

– Catalina bison photo courtesy Catalina Island Chamber of Commerce & Visitors Bureau –

– All images courtesy Library of Congress –