When Kenneth J. Zoll and his wife Nancy retired to Sedona, Arizona, in 2004, Ken had never heard of “archaeoastronomy.”

After all, he had spent 35 years working in federal offices, ending up as the chief technology and information officer for the Railroad Retirement Board in Chicago. He found himself in retirement blessed with good health, strong legs and knees, and a keen mind filled with curiosity.

Ken joined a group called Friends of the Forest, who maintain the hundreds of miles of hiking trails around red-rock bedazzled Sedona, monitor water in Oak Creek and maintain the apple orchard at Slide Rock State Park. He volunteered with them every Friday, and eventually he was assigned to the V-Bar-V Heritage Site, about 12 miles southeast of Sedona within the Coconino National Forest.

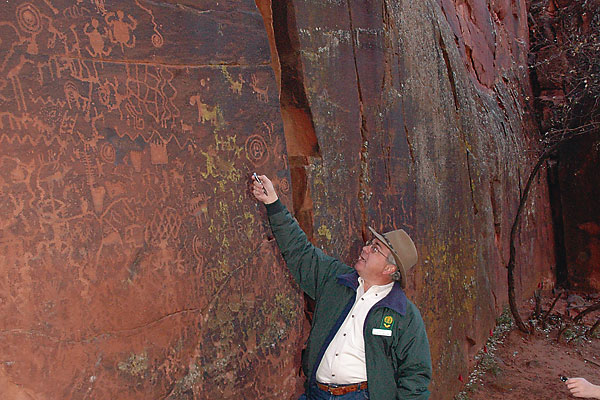

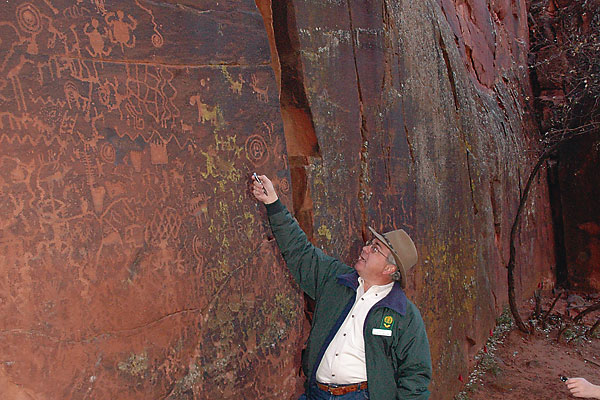

This was most recently the site of a thriving cattle ranch, nestled along Beaver Creek, but that came centuries after it was settled as an agricultural community by the Sinagua, ancestors of the Hopi tribe. Evidence still exists of the massive fields that made this site the “breadbasket” of the Verde Valley in the 11th century, but even more important, the Sinagua people left behind some 1,032 petroglyphs on a half-dozen rock wall panels, telling the stories of their lives.

These “scratchings” in the rocks fascinated Ken. “I was there about a year, and I noticed seven concentric circles on one panel, but no circles on any of the others,” he says. “I went to the library and checked out books on rock art.” His first clue was a reference to ancient tribes using concentric circles to create solar calendars. It got him wondering.

One day, he was visiting with the resident couple who stay on the site for the forest service, and they mentioned that they’d noticed the sun coming through two rocks and making a pattern across one of the panels. Ken was ready, camera in hand, in February 2005 for the Equinox. He saw the sun come through and match up with some of the circles. “Oh, maybe we have something here,” he thought. “Maybe these circles are indeed a solar calendar that told the tribe when to plant, when to harvest.”

He approached the local archaeologist for the forest service, Peter J. Pilles Jr., who gave Ken a sobering reaction: “He said he was skeptical and he was dubious, and told me I’d need a year’s worth of evidence before we’d know if we had anything. But he gave me a set of keys so I could get into the site anytime.”

Ken was not to be dissuaded and spent hours documenting the panel all that spring. After the Summer Solstice, when the sun again followed the markings of the circles, he went back to Pete with his convincing evidence. Ken will never forget what the archaeologist said: “Ken, how do I argue with this?”

Within a year of coming to a new state and of learning its ancient ways, Ken Zoll had discovered the Sinagua’s solar calendar.

In 2006, he wrote the book Sinagua Sunwatchers: An Archaeoastronomy Survey of the Sacred Mountain Basin, which is sold to benefit two groups that are preserving archaeological sites in the Verde Valley. Ken has also become a favorite speaker to the local chapters of the Arizona Archaeological Society.

Since his first discovery, he has identified 10 other calendars at sites in the Verde Valley, saying he went from “the high-tech of the 21st century to the high-tech of the 11th century.” Although self-taught in archaeoastronomy —a discipline that interprets rock art—he has received his teaching certificate on the subject from Todd Bostwick, the City of Phoenix archaeologist.

He is working on creating the first academic conference on “ancient astronomy” during the Festival of Native American Culture planned for June 5 to 13 in Sedona.

“What I really, really enjoy the most is when I explain the calendar and people tell me ‘I had no idea these people were so sophisticated and talented.’ There’s a changing perspective. The Sinagua were just as smart and sophisticated as the Inca or Mayans. These people were not ‘savages,’” Ken says.

The next discovery awaits this man who hikes into the mountains in the pitch black of night, for he must arrive before sunrise to track the path of the rising sun. He may extend these trips to overnight stays, so he can explore the patterns at sunset.

His wife worries about his jaunts into darkness, but she admits the discomfort is worth it, he says, since he is helping bring more understanding of prehistoric people.