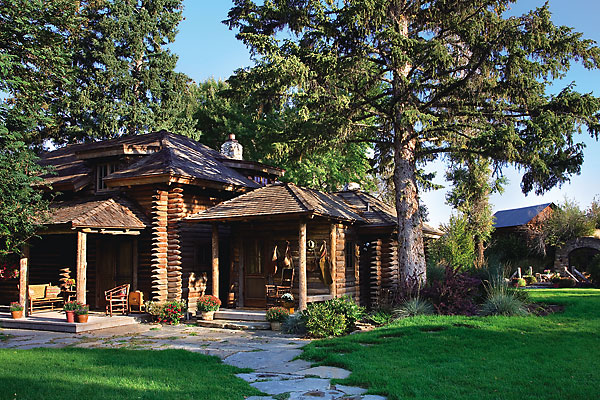

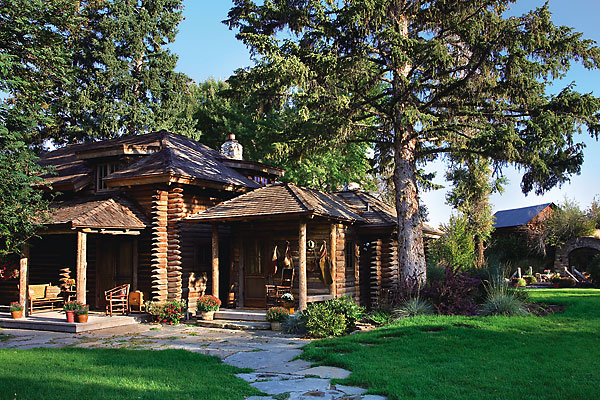

It took a decade to find the property that Mike and Amy Bennett envisioned: a classic little log building not unlike the trailside museum at the confluence of the Madison and Gibbon Rivers in Yellowstone National Park, with a little stream out back, a meadow and lots of trees.

Mike would know it when he saw it, he told his friend and fishing guide, Randy Cain. Then one day, driving along the old gravel road on the east end of Ennis Lake, he spotted his cabin through the trees.

They turned into the driveway to get a closer look. The place wasn’t for sale, but Bennett was smitten with it and eventually negotiated a deal with owner Jack Watkins Jr., a third-generation rancher.

“There was a lifetime accumulation of stuff that a typical rancher would collect, but I could see that the bones of the building were in incredible shape, and I thought it was gorgeous,” Mike recalls.

During the negotiation of the property, the Bennetts learned about the rich history of Watkins Creek Ranch. The Watkins family was one of the first to raise cattle in the Madison Valley in the late 1800s. The main house was constructed in 1906 by Jack Watkins Sr., who was a chief carpenter in the construction of Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Inn. He applied the skills and artistry he’d learned on the job to his own family cabin, for which he harvested long, straight lodgepole pines and carefully stacked and chinked them to create a humble, but thoughtful, abode.

In classic cow camp style, smaller cabins were added to accommodate ranch hands, storage and livestock, and it was these outbuildings that sparked Mike’s interest in creating a ranch compound. Shortly after he acquired the property, he began interviewing architects and contractors to restore the main house. A developer and contractor in his home state of South Carolina, Mike had been restoring historic buildings in Charleston for nearly 30 years.

Ultimately, Mike chose to work with Candace Tillotson-Miller of Miller Architects and Harry Howard of Yellowstone Traditions. “I think they both really appreciated the house,” he says. “Rather than say, ‘It’s an old house that needs a lot of work,’ they said, ‘This is a rare find.’ It’s a charming old building and it needs some tender, loving care.”

Mike wanted to create a ranch compound with a series of small buildings rather than one grand mansion. Miller helped finesse the concept, and the work began. The road was rerouted, the classic weathered buildings were relocated closer to the main house and the property, which was overgrown and neglected, was cleared of junk, including 31 abandoned Cadillacs.

Miller inventoried the existing elements of the main house and outlying buildings, and then carefully enhanced them. Working with Howard and Yellowstone Traditions, she was confident that the sensitivity for the historic quality of the project would be a priority.

“All of us were so endeared by the scale and detail of the house,” Miller explains. “It’s this kind of elegance and intimacy that we try to replicate in new projects.”

Miller quickly realized that there was much more to the property than the main house, such as the walkway through the century-old lilac hedge, the shade of the towering cedars and the sense of shelter that the land offers with its natural configuration in a drainage of the Madison Range. And then there is the broad view across the hayfield toward Ennis Lake and the ever-present sound of Watkins Creek. She wanted to piece each ingredient together to make the ranch complex feel more diminutive and less industrial.

One way Miller accomplished this was to change the approach to the house from the main road, rerouting it to amble along a stand of cottonwoods, concealing the house until the final crossing over an irrigation ditch into the driveway. She added front and back porches to the main house, along with French doors to accommodate indoor-outdoor living. Yellowstone Traditions built the extensions, carefully matching the newly added log to the original structure, which features dovetailed corners with “beaver tail” log ends.

Inside, the overall floor plan of the 2,000-square-foot home had an open flow, and the condition of the logs was remarkable. To lighten up the dark interior, Miller added taller, deeper windows to replace the original “matchbox” ones. The kitchen, which had been home to a multitude of cats, was reclaimed and modernized. But on the whole, Miller’s approach was to “land lightly” and work with the amenities that already existed within the historic cabin.

Interior designer Diana Beattie, of Diana Beattie Interiors, New York, outfitted Watkins Creek Ranch as though it were her own. Mike Bennett approached her to complete the interiors within a few weeks, with the directive, “Make it look like Teddy Roosevelt lived here.” Beattie, whose expertise is in embellishing a traditional rustic style for contemporary living, rose to the challenge. Relying on her long-term supplier relationships and connections with local artisans for custom furnishings, and incorporating pieces from her own collection of 1930s handmade Old Hickory furniture, Beattie drew on her passion for the Adirondack camp style. She crafted elegant living spaces that masterfully complement the time and place of this home, using a natural palette of color to allow the structural beauty of the log cabin to stand out.

In the great room, the original elements of the home steal the scene: the twisted juniper banister that leads upstairs to a loft; the white quartzite fireplace made from stones found on the property; the dramatic pendant light that showcases three bighorn sheep harvested by the original owner. Rather than challenge these unique elements, Beattie enhanced their presence by placing furnishings with a subtle hand.

She combined classic rustic pieces with antiques to echo the era when the home was built, a time when homesteaders typically had a few stand-out family heirlooms in addition to their simple furnishings. An antique Swedish chest was placed between the leather furniture, a Black Forest breakfront sits in the corner and an intricate round Adirondack table supports a reading lamp—each bringing a personalized eclecticism to the room. Kilim rugs add a jolt of color to the woodsy brown scheme, and original paintings by regional artists punctuate the sense of place in the cabin. Also key to the interior design was Beattie’s ability to blend masterfully crafted furnishings by artisan David Black and lighting created by “Fish” Fisher of Fish Antler Art.

The three bedrooms are tucked down the hall from the main living space, each decorated with brightly colored linens and well-placed handmade furniture. In the master bedroom, Black crafted an intricate willow-twig headboard with carvings by Jans Carlsen: a trout swimming on award-winning angler Amy’s side, and a bevy of quail on bird hunter Mike’s side. Bringing in the work of contemporary artists was a way of honoring the original craftsmanship of this historic home, and it was an essential element in connecting the compound’s separate buildings.

Back outside, a path leads from the back door to extended living spaces along the creek. Thoughtful landscape design, flagstone paths and perennial plantings link the different structures.

Over the bridge is the smoking room, carved into the hillside by the original owner like a bunker. Miller called upon master blacksmith Bill Moore to craft an arched metal and glass door for the space, which houses a custom billiard table and accommodates outdoor dining on the terrace.

In the other direction, the path leads to the cozy fishing cabin. The restacked log cabin is a departure from the main house, in that the huge, many-paned window looks directly toward the lake. Yet the simple style of the cabin is in line with the “Parkitecture” influence that exists throughout the property. Waders hang outside on the small porch. Inside, an Adirondack-style twigged fly-tying desk is the central focus and activity for this creekside structure.

Farther up the creek is a building that resembles a traditional bunkhouse. It’s the Dog Trot—two original cabins that were reclaimed, relocated here and connected by a single porch. Used as guest quarters, each cabin has one bedroom, a private bath and kitchen facilities. Vintage oil lanterns decorate the exterior logs under the covered porch, where stairs on the backside lead to a flagstone fire pit along the creek. Inside, spare but tasteful rustic furnishings and kitschy camp art continue the playful, historic Western style.

Furthering the cow camp concept of connectivity, the Bennetts extended the ranch property to include Ennis Lake, with an outdoor pavilion and boathouse in progress down at the lakeshore.

They also plan to enhance the outdoor dining area for summer gatherings by converting an old woodshed into a custom kitchen for entertaining. Miller notes that while the compound allows the Bennetts privacy, it also provides the family with the ability to get together in a variety of spaces, moving from one building to another and utilizing the entire property. In the long run, the idea is to remain close to home.