The discovery of gold in 1874 by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s expedition ignited a stampede.

Mining camps sprang up in the Dakota Territory’s Black Hills—Deadwood being the most notorious. One of the routes to Deadwood originated in Fort Pierre. On the Missouri River’s west bank, Fort Pierre was a natural stop for freighters transporting goods to goldfields. Steamboats brought cargo up the Missouri. In 1880, when the railroad reached Pierre, it unloaded freight that was ferried across the Missouri and loaded into wagons.

Bull and mule trains freighted tons of supplies over the Fort Pierre to Deadwood Trail until 1908, when the advancement of railroads through the Black Hills prodded pioneers off the trail.

Today the trail meanders through both public and private land, making a trip across it impossible…until last year’s historic journey.

Rediscovering the Trail

Rancher Roy Norman had a dream to mark the trail before it was lost. In the 1970’s, he traced trail ruts and placed 52 wooden signs interpreting the trail.

Darby Nutter, president of Fort Pierre’s Verendrye Museum, had a dream to ride the trail with friends. South Dakotans Lonis Wendt, Paul Seamans and Sam Seymour acted on their dream to GPS the trail.

In 2007, these trail enthusiasts joined forces, selecting Gerald Kessler of Fort Pierre to be wagon master and appointing outriders to assist the 300 trail riders. Sixty-four speakers told trail history at evening camps, accompanied by musical entertainment. Organizations were lined up to provide meals. The committee also set up easements, insurance, water, porta-potties and trash pickup, and coordinated with ambulances, fire departments and law enforcement.

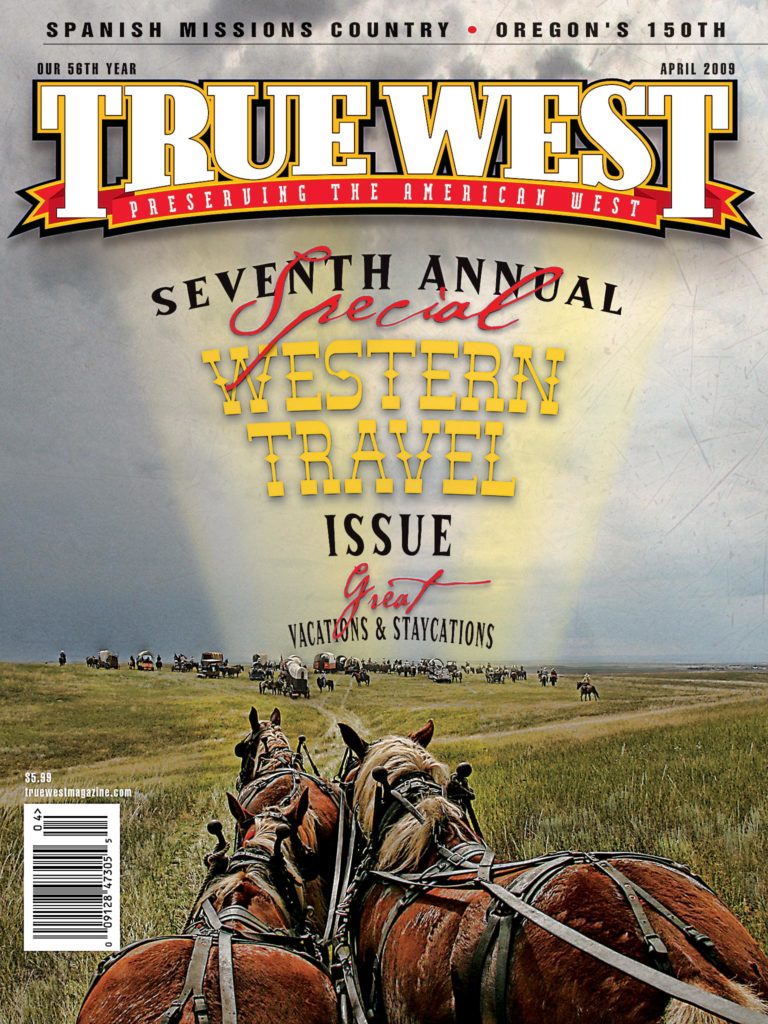

The wagon train would travel 240 miles in 17 days; two would be rest days. I was riding with James and Teri Todd of Harrisburg, South Dakota, who had three saddle horses and a wagon pulled by four Belgian horses.

As we enjoyed opening night festivities at the Fort Pierre rodeo grounds, one issue remained unresolved. The wagon train needed to cross one-eighth of a mile of U.S. Forest Service land; after nine months, the agency still had not signed the easement. Without it, the wagon train could not faithfully follow the trail into the Black Hills.

Day 1: Wednesday, July 30

“Wagons Ho!” shouted Gerald, starting 54 wagons and 200 horses and riders on their journey out of Fort Pierre. I rode as an outrider alongside James’s team. “I want to be toward the wagon train’s rear so I can see all the action,” James said. Cheering crowds lined Main Street. The wagon train turned west and began the ascent of the bluffs. “When I began the climb out of Fort Pierre, I could not see them, I could not hear them, but I could feel the presence of all those souls who had gone out of Fort Pierre on that trail encouraging us onward,” said Mike Pellerzi of Canning, South Dakota.

The hot muggy day was unkind. Horses and mules bucked off riders, leaving them with broken bones and cracked ribs. A riderless pinto raced through a lunch stop knocking over four people. A spooked horse smacked my head, sending my glasses sailing off into the tall grass never to be found again and giving me a nice rope burn on my left hand. I had my doubts I would make it to Deadwood as Gerald fixed up my hand; but a smiling Darby said, “Bill, cowboy up!”

Day 2: Thursday, July 31

Mike Pellerzi has worked cattle and rodeoed since the age of 14. He rode on a commemorative saddle he had made for the ride. My saddle belonged to Mike’s friend T.R. Stalley, of Riverton, Wyoming. T.R. had died of a heart attack, and Mike was taking the saddle over the trail to honor T.R.’s memory.

The wagon train crossed country where wagon wheel ruts had scarred hillsides. The jingle bobs on Mike’s spurs tinkled as he rode along—“cowboy wind chimes.”

Day 3: Friday, August 1

James’s father Arlo, Alvin Kangas of Lake Norden, South Dakota, Howard Main of Gallup, New Mexico, and I rode four abreast.

Family legacy brought us all to the trail. Alvin’s father owned working horses on the farm; it was the same for Arlo, who added that his grandfather had been a freighter on the Fort Pierre to Deadwood Trail. Howard’s grandfather was a teamster in the Dakotas and Montana. “I hope to experience and see what my grandfather would have seen and the things he would have endured while freighting on the trail,” he said. As for me, my Dad had instilled in me a love of the West.

During lunch, a runaway team broke the wagon tongue belonging to South Dakotan Mike Roman. With American can-do spirit, he replaced the tongue and continued on.

We passed the site of a ranch where, from 1901-03, Wilhelm Kunnecke murdered six hired hands instead of paying them.

I rode alongside Darby. “I used to cowboy in this country,” he said. “This is where I first saw the trail ruts and wanted to follow them to Deadwood.”

Day 4: Saturday, August 2

I learned to hold two grass-munching Belgians by their lead lines in one hand while eating a baloney sandwich.

The temperature felt to be 102°F. There was constant dust. I fell under the spell of the rhythm of Teardrop’s walk, appreciating the shade of a cloud and the wisp of a breeze.

Day 5: Sunday, August 3

I rode alongside James in his wagon. “My great grandpa, John Wesley Todd, freighted out of Fort Pierre,” James told me. “He drove a six-hitch mule team hauling lumber from Kansas to the site of Blunt to build the town. He hauled freight out of Fort Pierre west…. To be on the trail he was on and experience some of the things he did, that’s kind of my whole purpose. It’s ironic he freighted in his day with mules, and I’m freighting today with big trucks. I guess it’s in my blood.”

“I’m having a great time and meeting lots of nice people,” Shirley Simonsen, of Viborg, South Dakota, said. “My horse fell over the first day. I have really achy ribs, but I’m going to the end—still heading west to Deadwood.”

The wagons proceeded westward, crossing unbroken prairie. On the horizon stood the three Grindstone Buttes. They appeared biblical—like the children of Israel headed toward the Promised Land. I could see how the pioneers must have felt. They were on a mission to build a better life—in a way, maybe so were we. Would we all be the same after this ride?

People ranging in age from seven to mid-80s traveled the trail. Kids played tag on horseback. Young lovers rode side-by-side holding hands. People climbed in each other’s wagons to visit. Riders passed the time on horseback talking to each other. Some were loners keeping to themselves.

That evening, Gaylord and Zay Norman reminisced about Roy.

“My father wanted to preserve the trail so people would know where it ran,” Gaylord said. “As a boy in 1908, my father moved from Fort Pierre to Grindstone traveling the trail.”

“My brothers and I rode around with my grandpa,” Zay said. “I must have been 10 years old. One time sticks in my mind. We came out to Willow Creek where we spent the day planting signs. We put up the last sign along a fence. It seemed like we’d been driving in pasture all day. I said, ‘Who is ever going to see these signs? Are we doing this for nothing?’ He goes, ‘Oh no! This is something everybody will want to know about. There’s going to be historians who will want to know about the trail.’ We were two miles from the highway. Years after that, they moved that highway and now it goes right by that sign and everybody sees it. That’s special to me.”

Day 6: Monday, August 4 (Free Day)

A violent storm swept through—with rain pelting and winds blasting down tents. Three horses went missing but were later found leisurely walking back to the trail.

Day 7: Tuesday, August 5

Lamont Hill, 71 years old, was bucked off his horse. Fellow riders cared for him until the ambulance arrived. Surgeons removed his damaged spleen at the hospital, but several days later Lamont died of complications.

The wagon train crossed prairie along the southern Grindstone Butte, stopping at the grave of four freighters murdered in 1876.

We pushed on through dust and heat. Up a hill and down, up a hill and down—ever onward. People were hot and tired. There was little talking. We moved steadily forward to the sounds of rumbling wagons, creaking leather and working animals.

Day 8: Wednesday, August 6

We visited Peno Springs. It’s on private property, but the landowner allowed us to see it. The landowners have been gracious. Many even cut their own fences to allow us to cross right on the trail.

We followed trail ruts through steep hills with tree-lined streams. On a rise above the springs sits an 1878 stage station. Abandoned, it is still in good shape.

Leaving Peno Springs, the wagon train climbed a long steep grade. The going was tough the last few hundred feet to the top. Mike Pellerzi and other outriders tied lariats to wagons to help pull them upward. We rode a hot, grueling 20 miles. The most relaxing part of the day was watering the horses.

The Milky Way dominated the moonless night sky as I talked to my wife Liz on my cell phone. I can’t imagine the pioneers’ loneliness, leaving loved ones behind.

Day 9: Thursday, August 7

Recent storms increased the flow of the Cheyenne River to five feet, a height too high for most wagons; we hoped the level would decrease by the time we crossed tomorrow.

Mike Pellerzi turned 63 today: “Only one thing would be better than this [ride], and that would be working cattle in Wyoming.”

At the evening program, Miniconjou Lakota Dave Bald Eagle spoke: “I cannot participate in this trail ride because the trail was used to bring equipment to dig gold in the Black Hills.” Dave paused. “Tomorrow I will have 150 Lakota warriors on the far bank of the Cheyenne to prevent you from crossing.” The audience was silent. “That’s a joke,” he said.

Day 10: Friday, August 8

James was nervous, “My horses have crossed flooded roads but never a live river.” He wanted his wife Teri and me to ride alongside the Belgians to help guide them across the Cheyenne River.

Darby had crossed earlier. “The water is stirrup high,” he told us. “The wagons should make it across.”

Wagons began crossing one at a time. The flow was swift and the color of vanilla ice cream. The Belgians plodded to the bank into the water and safely made it across.

We waited with other wagons beneath gnarled cottonwood trees. Soon talk of a wreck sped up the line. A stagecoach team of six horses had broken away, running over 80-year-old Bud Hall, from Fort Pierre, breaking his jaw. A helicopter airlifted Bud to a Rapid City hospital where he recovered.

Once we all reached the Cheyenne River valley, each wagon proceeded up the steep grades in stages—climb to a level area, stop, wait for the wagon in front to pull up to the next level area, then tackle the next grade. James coaxed the Belgians up the slopes without a problem. The climb was long, but the horses had plenty of resting points. One last steep pull and we were on top.

Day 11: Saturday, August 9

The day was clear and hot. Across rolling prairie, horses’ hooves and wagon wheels crushed sage plants releasing their fragrance.

Mike Greslin rode beside me. The trail crosses his property near Fort Meade. “I knew the wagon ruts were there,” Mike said. “But I never had much interest in them. When the committee contacted me about crossing my land, I said ‘okay,’ but only had a mild interest. Two weeks before the ride, my interest began to grow. My great grandfather was from Italy and came west to Belle Fourche on the trail. Now riding it has piqued my interest to learn more trail history. I’m proud to have the wagon train cross my property.”

Looking down, I saw shards of broken china along the trail—maybe from a dish that fell out of a wagon long ago.

Clouds building in the west provided relief from the sun. I saw for the first time in their entirety the Black Hills, extending south to north, dark purple on the horizon. The grassland continued to the Hills.

Mike Pellerzi reined up beside me. “That’s some sight. What would you think if you were the first to see that?”

“I’d say, ‘I need to ride over there and see it.’”

Day 12: Sunday, August 10 (Free Day)

Liz came for a visit. We drove to a truck stop where I took a shower. The wagon train was two-thirds of the way to Deadwood. I hated to see the trip end.

Day 13: Monday, August 11

At the evening campsite, I sat talking with folks on the Kammerer family ranch.

Twelve-year-old Cody Witte, of Fort Pierre, was on a mission: “I came to help my Dad get around. He hurt his back last September. His motivation to get better is for us to do the whole trail.”

Doug Hansen, who builds and refurbishes wagons in Letcher, South Dakota, told me about his beauty. “I had this stagecoach layin’ behind the barn. It had traveled the Deadwood Trail. We started putting it together, finishing right before the start of the ride. Since the trail was a freight trail, I thought, ‘Man, we need a freight wagon,’ so we built one. The freight wagon’s running gear is a restored Studebaker. I’ve built wagons 30 years, and it’s taken me this long to figure out how freight wagons worked because there is no documentation. There’s none in the museums. I studied historic photographs and hardware I collected. I think everybody here appreciates seeing that freight wagon on the trail.”

Dick Herman, of Fort Pierre, told me, “I rodeoed for 33 years—started out riding broncs, then I got hurt in ’86. I’m an outrider, so I help if someone needs assistance. I was there when the stagecoach wreck happened. It wasn’t that bad. I’ve been in barroom brawls worse than that.”

Clay Austin, driver of the stagecoach with Todd Bender, shared their wreck with me: “I was being drug by the foot. Todd got loose, then the reins unraveled around my boot and I was free. The stagecoach came apart the way it was supposed to, to save passengers.”

With the help of local ranchers, they had gotten the pole fixed, and the stagecoach was back on the trail.

“If your stage broke down on the trail you didn’t crawl in a hole and die, you made do with the resources available; you uprighted your stagecoach, patched it up,” Doug said.

“The best part was coming up out of the Cheyenne,” Todd added. “I looked back down in that valley and said ‘C’est la vie, you son of a buck. We beat you this time.’”

Day 14: Tuesday, August 12

Michelle Barrett, of Pueblo, Colorado, joined the trail ride seeking adventure. Tragedy had struck 18 months earlier when her husband was killed in an auto accident. “I do lots of trail riding so I expected a really good trail ride,” she said, “but it’s turned into a life-changing event—reconnecting with who I am and what my dreams are.”

We had arrived at the Black Hills.

Day 15: Wednesday, August 13

Three sisters were riding together: Darlene Goemer, Adella Kills Pretty Enemy and Trudy Carpenter, all from South Dakota, although Darlene lived in Michigan. They try to reunite each year and love to sing together, which they did at the trail’s evening programs.

“We’ve never been on a ride this lengthy,” Trudy said. “We got to know lots of people. My son broke his ankle on the sixth day. He was thrown off his horse—hopefully he’ll be back for the end of the ride.”

“Our mother belonged to the Chippewa Tribe,” said Darlene, with Adella adding, “And this hat I’m wearing belonged to our grandfather. I wear it to honor him.”

“I was bucked off my horse the first day,” Darlene said. “Trudy’s horse ran away one day, and Adella’s bucked with her yesterday, but she rode it out, with the people around her giving her a rodeo score.”

Helen Gaskins has been on many trail rides in her 73 years. She carried a small tank in a backpack supplying her oxygen. “I was seriously ill, sitting in a recliner and using a wheelchair, when I heard about the trail ride. I started thinking about doing it. ‘How are you going to pull this off?’ my husband asked. I thought about it overnight. Next morning, I said, ‘I might be foolish; but I’m going to get well enough, and I’m going.’” And she did.

Rancher/author Mel Anderson rode toward the front, having rejoined the wagon train after his hospital stay. Grouse had flown up from a ditch, striking Mel’s horse in the breast. The horse bucked, tossing Mel, who broke his collarbone and cracked his ribs.

The team and wagon emerged at Fort Meade, built in 1878 to protect settlers.

Day 16: Thursday, August 14

The wagon train paraded through Sturgis, past cheering crowds lining the streets. We rode along I-90, and then we traveled across the controversial Forest Service land, off limits until a few days ago. Our evening camp in Boulder Canyon was dreary and rainy.

Matt Trask played a song about the trail he was composing on his guitar. The 29-year-old humor columnist for a Pennington County newspaper said: “I’ve got to hand it to those old boys who traveled this trail long ago. They had to go to Deadwood or Fort Pierre with what they had. If something goes wrong for us, we have our cell phones, radios and pickups. I’ve been praying for the safety of the wagon train every day.”

Day 17: Friday, August 15

“Wagons Ho!” shouted Gerald for the last time, as we went onto the highway, lined with people yelling “Thank you” and “Good job!”

We came down one last steep grade into Deadwood Gulch, crossing the city limits. Crowds lined up to greet us. I saw Liz with our neighbors Julie and Bernie Linn.

Trail riders joked we should keep riding west—well, we were only partially joking. These people, strangers who were now friends, would never be all together again.

That evening, Liz and I entered Saloon Number 10 where we met up with friends from the trail. Mike Pellerzi was parked on a stool at the edge of the bar, unable to move. The bouncer had told Mike to stay where he was or take off his spurs—might hurt someone in sandals. “What’s this country coming to when you can’t wear spurs in Saloon Number 10?” asked Mike, as he bought me a shot of Windsor.