Film historians like to talk about the great lost movies, films that were mutilated or mishandled. They talk about changing scripts, reshot endings and rotten marketing—archetypal Hollywood mythology.

Film historians like to talk about the great lost movies, films that were mutilated or mishandled. They talk about changing scripts, reshot endings and rotten marketing—archetypal Hollywood mythology.

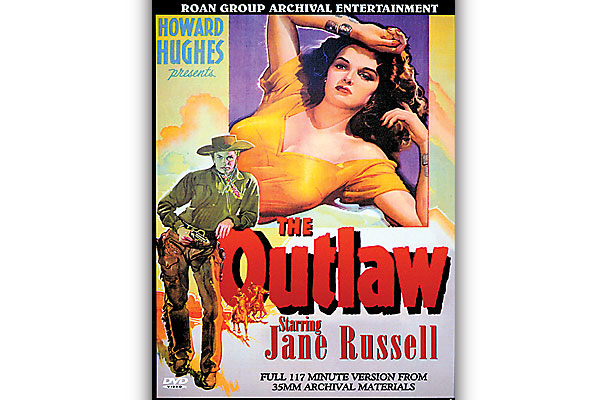

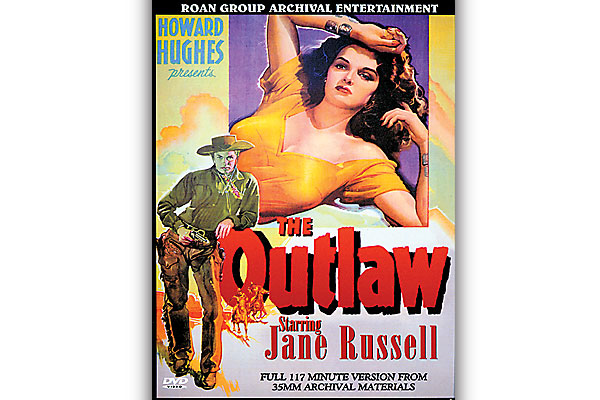

Howard Hughes’ The Outlaw, which opened in 1943 and again in 1946, was an infamous misfire. It was also a textbook example of how egos and ineptitude can utterly ruin a potentially great film and still make a tremendous profit.

Even today the movie is mostly famous for the debut and display of the 19-year-old Jane Russell’s considerable bust, but The Outlaw is a good deal more interesting than that, and it’s not because of Russell’s cleavage, but it is because of the sex.

What’s strangest about The Outlaw is that the buxom Rio (Russell) is not the object of desire in the picture—in fact, she barely registers at all. Actually, an entirely different sort of triangle is at play here, and it’s between the older Doc Holliday (Walter Huston), the brash young gunslinger Billy the Kid (Jack Buetel) and the paunchy and freakishly jealous Pat Garrett (Thomas Mitchell). The movie teaches us that Hell hath no fury like a sidekick scorned.

It turns out Garrett and the legendary Holliday used to run together before Garrett put on the Lincoln County sheriff’s badge. When Holliday shows up in town one afternoon, Garrett is so thrilled to see his old pal, he’s practically licking his chops.

Doc is glad to see his buddy, but he’s also keeping one eye peeled for his prized strawberry roan that someone stole. Who should turn up in town with the horse than William Bonney a.k.a. Billy the Kid, all low key and lanky. A few words and a little pawing make Billy and Doc an instant item—they do the same kind of stalking dance that the older Humphrey Bogart and young Lauren Bacall did in To Have and Have Not (1944).

Make of it what you will, but keep an open mind, and remember that both The Outlaw and To Have and Have Not were developed by the same director and writer, Howard Hawks and Jules Furthman (more on that below).

Meantime, Rio appears for the first time, wanting to put some holes in Billy because her brother died when he drew on the Kid. Rio shoots at Billy in the dark, they tussle on the stable floor, have a brief conversation in the hay and then do some more tussling. “Hold still lady, or you won’t have much dress left,” we hear Billy say in the dark. She holds still. Rape? Maybe. Sex? Without question.

The next morning, he and Doc pick up where they left off. Garrett is so apoplectic, he plugs Billy. Doc and the Kid take it on the lam; the barely conscious Billy winds up in the care of Rio and her tia Guadalupe (a great bit of work by actress Mimi Aguglia), and Garrett leaves to deal with the posse.

Turns out Billy needs a lot of looking after, and when Billy’s chills aren’t helped by Rio’s heated stones, it’s only natural that she remove her clothes and climb in bed with him. Long fade.

Weeks later, Doc returns and quickly figures out that another mule is kickin’ in his stall. After a little huffing and puffing, Doc and Billy go back to arguing about the horse and swapping meaningful glances. All’s fair in love and horse trading, and Rio goes from being company to a crowd.

This is peculiar stuff, to be sure, but one gets a sense of how original this movie might have been had it not been run over twice or three times by Hughes’ ego.

Hawks was originally hired to develop and direct The Outlaw, which would have made it his first Western (Red River was filmed several years later). He brought in writer Furthman who he had worked with twice before and would again collaborate with on To Have And Have Not and Rio Bravo (1959).

But Hawks was not a filmmaker to tolerate interference. After two weeks of Hughes squatting over the production like a fussy hen, Hawks threw up his hands and walked, leaving Hughes in the director’s seat.

We can mourn the departure of Hawks because he loved to work magic with new actresses, and there is no magic to be found anywhere near Rio. Poor Jane Russell was only there to heave and pout and flounce about in this all-boy peacock parade. Some close-ups of Russell’s face are so atrocious, she ought to have sued.

The irony is that The Outlaw and Duel In the Sun, another feverish dust-luster, were the two most financially successful Westerns of the 1940s. In The Outlaw’s case, that success was entirely due to Russell’s chest and Hughes’ marketing of her chest. If audiences noticed the film’s campy style, they never made a point of it, but the movie was a real case of bait-and-switch hit.

The picture ultimately bellyflops because Hughes was an awful director and an even worse editor. Victor Young’s score with its atrocious comedy cues would have made more sense in a cheap cartoon or a Three Stooges short.

Which means this is not an easy film to recommend to the casual viewer because it just isn’t very good. Yet considering the movie’s place in history, the various personalities involved and the absolutely bizarre sexual undercurrents in the story, it is an amazing piece of work.

The 117-minute version on this disc seems to be as good, or as long, as it gets. It’s a pretty clean print, though far from perfect, and it could use a few extras.