While the six-gun may have reigned as king of the silver screen West, in the real Old West, it was a different story. True, the handy six-shooter played a pivotal role in both making the West wild and taming the land and its people, but it was the trusty long gun—be it rifle or shotgun—that was rated among the most important tools of the frontiersman.

While the six-gun may have reigned as king of the silver screen West, in the real Old West, it was a different story. True, the handy six-shooter played a pivotal role in both making the West wild and taming the land and its people, but it was the trusty long gun—be it rifle or shotgun—that was rated among the most important tools of the frontiersman.

The vast expanses of wild, unfriendly wilderness that made up much of the continent during the period of our westward expansion required that a man be well armed in order to survive. In these remote regions, a traveler needed to be able to feed, clothe and protect himself by his skill with a rifle or shotgun. The land was big, and the points of civilization were few and far between. Even during the latter phases of the frontier, wise wayfarers packed some sort of protection while traveling across open country.

Much has been written about the various arms used in the West during those years, but surprisingly little has ever been discussed as to how they were carried. Interestingly, many of the methods used by these early Westerners are as practical today as they were well over a hundred years ago, and the most commonly used methods of rifle packin’ were born on the American frontier. Let’s take a closer look at some of the ways our forebears toted their long guns from one place to another.

Toting Their Long Guns

In the early years of our westward push, long arms were aptly named. They were generally very long-barreled, and more often than not, single-shot arms, unless one carried a rifle with a swivel breech or a double-barreled shotgun. These guns were heavy and cumbersome and, for the most part, had been designed for the “long hunters” of the Eastern woodlands.

For several decades, the explorers, trappers and other travelers who ventured into the far west during the early 1800s simply carried their flintlock long guns and later on, their percussion arms. A man on foot most likely cradled his firearm in his arms, perhaps shifting it to different positions as he tired, much as a modern hunter does while walking through hunting country where game is really not expected. He could carry the lengthy rifle across his shoulder with the muzzle forward, gripping it by the barrel or fore-end. Or he could lay the gun across both shoulders, thus resting it behind his neck, with the weight of the gun supported by his shoulder muscles, while the muzzle points to the side rather than forward or to the rear. The military style of shouldering the arm with the muzzle in either the up or down position was also used from time to time. During a long trek, an individual would probably resort to all of these methods for short periods of time, shifting to a different hold as the muscles tired.

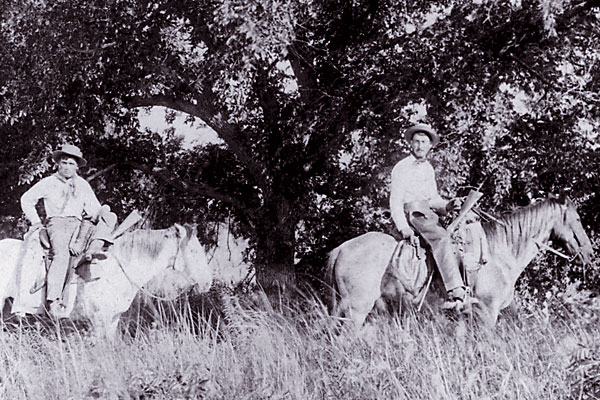

A horsebacker also relied on the above methods, especially cradling the gun in his arms. Being mounted gave him an advantage already, so his long rifle often rested between him and the pommel (front fork) of the saddle. A rider who carried a firearm with considerable wear in the fore-end section of the stock had likely logged in many hours in the saddle.

Evidence of two modes of gun carry by a single individual is provided by an excerpt from the chronicles of 19th-century Westerner William E. Webb. During his 1868 venture across the plains, Webb carried his recently acquired .44 rimfire “New Model Henry” carbine, better known today as the 1866 Model Winchester, by utilizing its shoulder strap and also dropping it across the saddle. He wrote, “I became very fond of a carbine combining the Henry and Kings patents. It weighed but seven and one-half pounds and could be fired rapidly 12 times without replenishing the magazine. Hung by a strap to the shoulder, this weapon can be dropped across the saddle in front and held there very firmly by a slight pressure of the body … and with little practice, the magazine of the gun may be refilled without checking the horse. So light is this Henry and King weapon that I have often held it out with one hand like a pistol and fired.”

Slings and Scabbards

Some fur trappers and early explorers carried their longarms encased in a soft cloth or skin-type covering. These scabbards were often made of deer, elk, moose or some other Western animal’s hide. The skin was tanned soft so that it was flimsy and cloth-like, with the hair usually removed. Then beadwork, colored cloth strips or panels and fringe would be added for decorative purposes. Trade blankets were sometimes sewn into colorful rifle cases, as was almost anything else that would serve the purpose of protecting the gun from the harsh elements of the frontier.

Slings, which are so common today, surprisingly saw little use in the Old West. Some frontiersmen made homemade versions out of buckskin, strap leather or heavy cloth, which were simply tied around the stock and barrel to form a crude sling. For horseback use, rifles with slings were generally carried in a diagonal position, with the sling passing over one shoulder and under the opposite arm. This allowed the horseman to ride comfortably with the slung rifle or shotgun held securely, but clear of the saddle.

Few American rifles were made with sling swivels in those days, and most of those were produced for the military. The New Haven Arms Co.’s Henry rifle of the 1860s is one notable exception. Some Henry repeaters were manufactured with sling swivels and were reportedly offered as the firm’s military model. A few surviving Henrys with what appears to be proper period-type slings have been noted, but such leather attachments are quite rare.

The Spencer seven-shot repeating carbine was produced with a sling swivel in the stock, but oddly, no provision for a sling was added to the fore-end section. This is because the company saved money by using one stock for both its rifles and carbines. The carbines were also fitted with the traditional cavalry-type carbine sling slide and ring, found alongside the gun’s left side of the receiver. Some users rigged up homemade straps for use with these carbines, depending on what models were being turned out by the factory at the time.

Commercially-made saddle scabbards, which are so commonly associated with the Western horseman both then and now, made their first appearance around the same time as the metallic-cartridge firearms. These longarms were generally shorter, lighter and much easier to handle, and their sleek lines made them more suitable to use in the saddle.

While some saddle-attached scabbards existed in the pre-Civil War years of the muzzleloader, such scabbards were usually the product of individual efforts. The lore, firearms and equipment of the American frontier reveals little evidence, in the way of existing specimens or photographic or illustrative proof, of their issue before the era of metallic cartridge arms. The few specimens noted were employed by the military during the Civil War, and again, those were homemade saddle scabbards, not commercially-produced models.

Packing Via the Saddle Scabbard

Westerners carried saddle-attached scabbards in a variety of ways. Probably the most popular means of packing a rifle via the saddle scabbard was the “northwest” position. The rider ran the connecting strap closest to the mouth of the scabbard through the fork of the saddle on the near or left side of a horse (the side of the horse that riders most commonly mount). They could run the rear strap through a rear latigo keeper or connect the strap by tying a loop in the cantle strings. The northwest position allowed the rifle to be carried, sights up, along the side of the animal. The rifle’s butt was forward, with the muzzle to the rear. Most often, the butt stock angled higher than the muzzle, although some riders liked to carry their longarms in a horizontal position. When toted in the northwest position, the gun was easily withdrawn from the scabbard. Should a horse go down for some reason or flounder through quick sand or a bog hole for example, the rifle was out of the way of his feet and not as likely to be damaged during such mishaps.

Some riders preferred a variation of the northwest position, in which the rifle was carried in the above-described manner but on the right or offside of the animal. With this mode of transport, the rifle was out of the animal’s way and could easily be pulled from the scabbard when needed.

I personally prefer this method, due to an old horsebacking injury to my left leg/hip area. Carrying the rifle on the left side causes me to extend my left leg a bit too far for comfort during any lengthy rides. When I pack it on the right side of the saddle though, the left leg is in a more comfortable position.

Riders who preferred the “southwest” position carried long guns on the right or offside of the horse, with the muzzle low near the stirrup leather and the butt stock sticking up high above the cantle or low alongside the animal. In steep country, the rifle stayed in the scabbard so long as the rifle butt was slanted upward at a good angle. Yet many longarms were lost by riders going uphill, due to the more horizontal southwest position of carry. Although this method was preferred and used (with the gun carried at a good upward slant) throughout the era of the Old West by the military, it was not as popular with civilian horsemen.

California Horn Loop

Another way of carrying a longarm, which remained popular in the open country of the West for a long time, was utilizing a simple device known as the “California horn loop.” The Westerner would make a loop from a small piece of leather, approximately 4-6 inches wide by around 10-12 inches in length. Into one end, he cut a crescent shape and into the other, a round hole. After folding the leather in half, first the circular opening was placed over the saddle horn and then, the crescent cutout. The Westerner then slipped the rifle into the folded portion of this makeshift scabbard, which held it in place (around the receiver section) in the saddle. In this horn loop, the rifle hung at an angle to the side of the saddle, allowing the firearm to be quickly withdrawn by the rider whether he was mounted or on foot. If desired, the gun could be left hanging from the saddle should the rider want to leave the rifle with his horse.

This method still works well in open country and offers a modest degree of comfort for the horseman, so long as the horse is walking. Any gait faster than a walk, and the rider is advised to rest one hand on the butt stock of the rifle to help steady the firearm and keep it from bouncing around, possibly slamming repeatedly into his chest or chin.

The California horn loop method of packing a rifle on horseback is not advisable in heavily wooded country, since the gun extends a foot or so from the sides of the animal and is exposed to brush, trees, canyon walls or any of the numerous obstacles encountered in dense terrain. This writer has used this method of carry and can attest to its merits and deficiencies.

In the Old West, especially during the pre-Civil War years through the early 1890s, the California Horn Loop was an extremely popular way to tote a rifle on horseback on the Great Plains.

Military’s Influence

The U.S. Cavalry, at one time or another, used almost every one of the above-mentioned ways of rifle carry. They adopted the horn loop for their Hope-style saddles (early military saddles that had a horn like a cowboy seat) and modified the loop for their hornless military saddles, such as the McClellan.

The California Horn Loop also saw extensive use by Canada’s famed Northwest Mounted Police. Some of the cavalry soldiers also employed simple carbine sockets to hold the muzzle of a cavalry carbine in place under their right legs. To attach their guns to their saddles, soldiers used short carbine boots or full-length rifle scabbards, depending on factors such as time period, region and the troopers’ preferences.

One feature that started with military carbines and eventually found its way to some civilian sporting arms was the “saddle ring.” Originally, this metal ring, usually found along the left side of an army carbine’s receiver and/or wrist of the stock area, was how a trooper attached his longarm to a leather sling worn over his shoulder. A steel snap, hook-type swivel was in turn attached to the sling. The horse soldier snapped this steel snap hook to the carbine ring, and with the aid of the socket or short carbine boot, could carry his longarm with him while mounted. Some civilian gun makers, such as Winchester, employed this military accessory to their carbine models. While a few non-military riflemen did employ the cumbersome sling on their guns and other Westerners tied their carbines to the cantle strings of their saddles via these rings, for the most part, such saddle rings were, and still are, vestigial appendages.

Still the “Old West” Way

While there has been a great deal of improvement in the rifles since the days of the Wild West, little has changed in the basic manner of transporting them. True, the modern rifleman is gradually leaning more towards synthetic materials for his scabbards, slings and rifle cases. Yet when it comes to packin’ his guns around, most of the methods employed in the days of the wild and woolly frontier are as practical now as ever.

Photo Gallery

This Cimarron Arms Henry replica is carried in a homemade “California Horn Loop,” a style popular on the open plains, but not very handy in heavily wooded country.

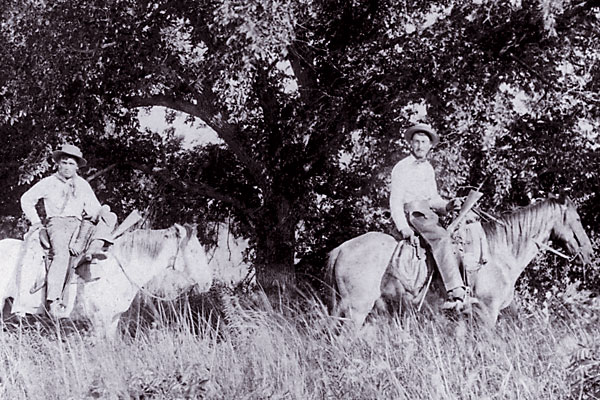

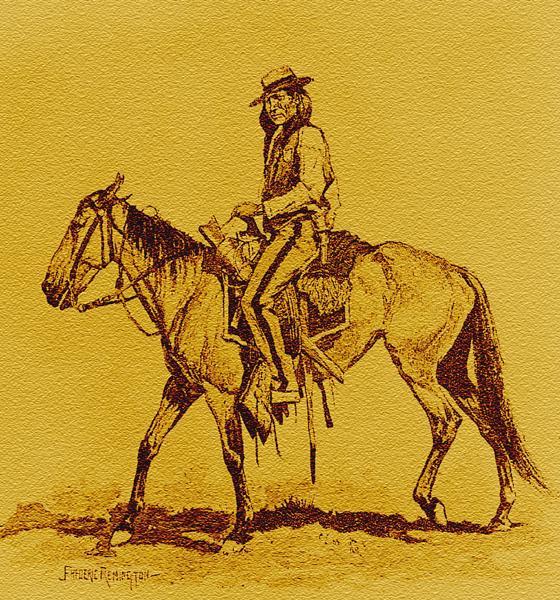

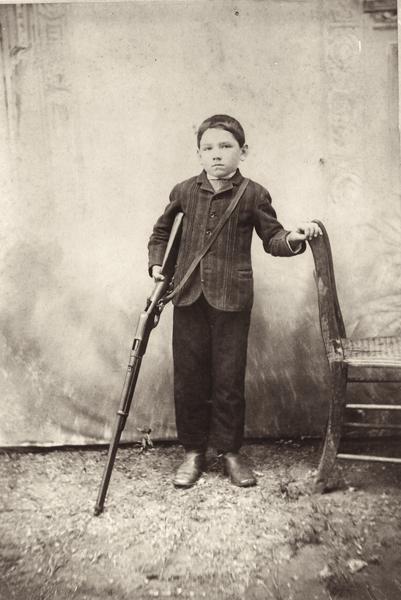

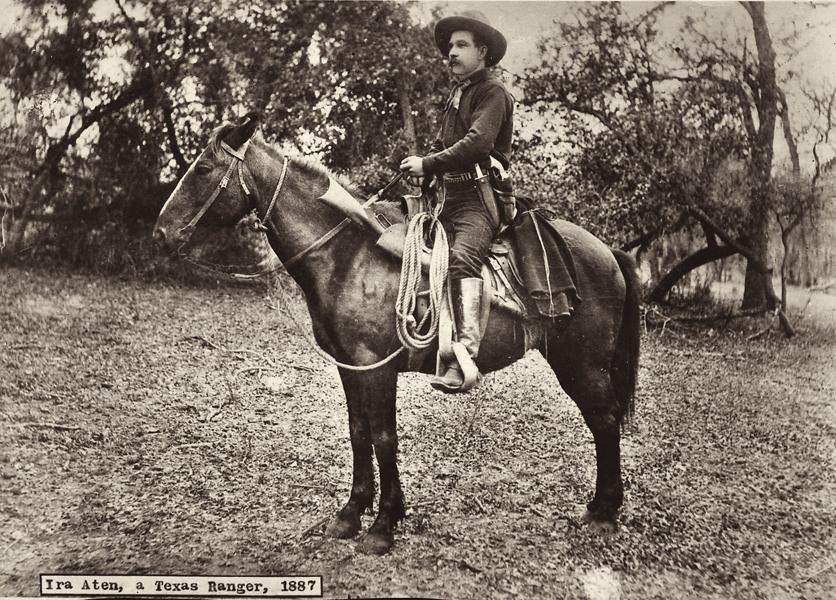

– Courtesy Herb Peck, Jr. Collection –

– True West Archives –

– All photos courtesy Phil Spangenberger unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy John Bardi and John Bell Collection –

– True West Archives –

This Dixie Gun Works 1873 replica carbine is carried in a saddle scabbard made by El Paso Saddlery, in the “southwest” position. Positioning the longarm in this horizontal placement is fine for flat country, but it could cause the loss of your rifle while going up a steep hill.